I built my first kayak in 1978. It was my own design, a mongrel of elements I’d seen in the classic documentary book, Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America, by Edwin Tappan Adney and Howard Chapelle. It had a stern profile from Alaska’s King Island, a midsection from Canada’s Southampton Island, and a bow from Greenland’s Disko Bay. I built it in fuselage-frame fashion as I’d seen my father do for his Hypalon-skinned interpretation of an umiak. I thought my kayak looked pretty good, and it served to get me on the water, but I clearly had learned nothing about traditional Arctic kayaks. When I paddled an old and rough reproduction of a Greenland kayak I got my first inkling of what I had missed.

The baidarka has 43 ribs, bent cold from saplings. They seem delicate, but they are all intact almost 30 years later. They were very easy to shape and the irregularities get smoothed out when the stringers are lashed to them. The “wings” connecting the stern block to the gunwales are curved toward the keel, not straight across as in Zimmerly’s reproduction, a detail that my friend John Heath pointed out.

In the years that followed I built reproductions of traditional Arctic kayaks to see what I could learn from them. In the early ‘80s I took an interest in Aleut baidarkas. John Heath, for years a leading authority on traditional kayak who later became a good friend of mine and a mentor to me, had taken the lines from an Aleut double and published them in Skin Boats. I built that kayak and was impressed by its speed and ability to rise over oncoming waves.

I stained the frame red with some artist’s oil paint mixed with linseed oil. The Lowie specimen was, according to Lantis, “painted with blood and a

powdered red mineral mixture.”

The ribs dried quickly and held the shape of the hull quite well.

Ten years later I had my eye on a single-cockpit baidarka documented by David Zimmerly in the February/March and April/May, 1982 issues of the now extinct Small Boat Journal. I happened to be in Berkeley, California, and visited the Lowie (now Hearst) Museum of Anthropology and was permitted to see that very kayak, an exquisitely crafted frame collected by Margaret Lantis in 1934 from Atka Island in the middle of the Aleutian chain. The woodworking bore the marks of the builder’s simple tools that the builder used; the bow and stern pieces, which wouldn’t be seen once the skin covering on, were as carefully sculpted as works of art.

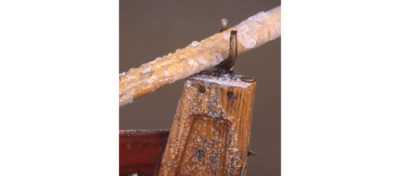

I carved the lower piece of the bow from a yellow cedar crook, so as in the original, it can be slender yet strong. The upper bow is in the shape of a T in cross section, and could easily be made from two boards joined together, but it is meant to be carved from a solid block.

Sewing the skin into the gap between the upper and lower bow pieces was difficult, but it was not merely for a decorative effect. The gap makes it possible to put increase the fore-and-aft tension on the skin so that it takes a convex curve from the sheer line to the keel. That flare, as in modern fiberglass powerboats, throws spray outward, and helps keep it from getting to one’s face.

Several years later, still captivated by the Lowie specimen, I began work on my reproduction of that baidarka. I had plenty of Alaska yellow cedar for the deck beams and end pieces, including a good crook for the curved lower bow, and clear straight-grained spruce and red cedar for the longitudinal elements. The ribs in the original were round in cross section and while Zimmerly milled his ribs from lumber, resawn, and rounded, but I decided to use saplings. I don’t now recall if saplings were used in the original; trees are scarce on the Aleutian islands. I harvested the saplings from a hillside overlooking Puget Sound. They grew in clumps, very straight and slender, and I found them very easy to bend and shape.

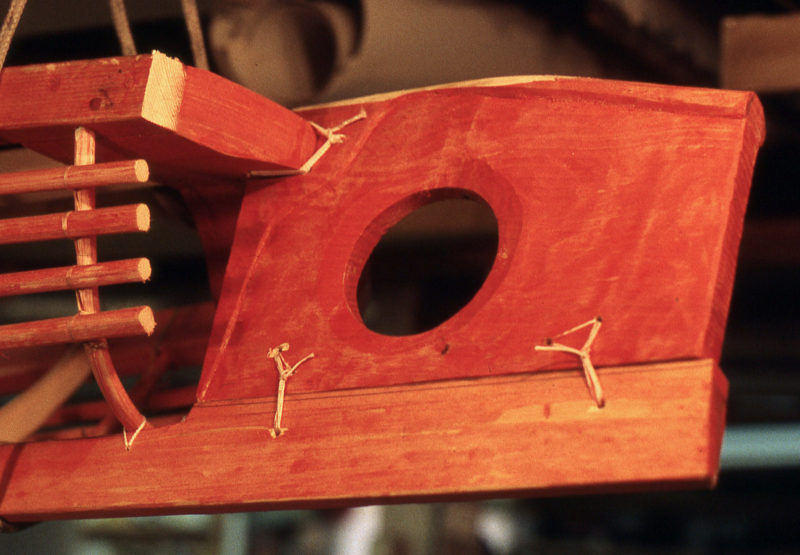

The hole in the stern piece was likely meant to save weight and perhaps to increase air flow to speed drying in the stern. The lashings holding that piece to the keel are extremely tight. They start with the lashing twine laced tight in a V shape between the 3 holes. Frapping turns pinch the V into a Y, greatly increasing the tension.

The unusual stern has the provides a lot of lift and forward drive in a following sea.

My baidarka was the first kayak I covered with nylon and two-part polyurethane instead of canvas and airplane dope. The dope was quite forgiving of application errors and was easy to work as long as I wore a respirator whenever I got near the vaporous stuff. The urethane was going to be a challenge for me, working alone, because it had to be put on continuously, coat after coat, and was very runny. I set up my drill press with a stirrer I made out of brass and while I was applying one batch it was mixing the next. That worked fine until the can at the drill press broke free and got spun by the mixer. In an instant the contents were flung from the can and splattered in a horizontal line across every wall in my shop and on any tool that happened to be stored at that height. I had my back to the drill press so I got a coating on the one part of me that wasn’t protected by my apron.

In spite of the trouble I had with the skin, I like that it is semi-transparent and lets the intricate framework show.

I eventually finished a serviceable if rather drippy coating on the baidarka skin. I’d been quite proud of the way the frame had turned out, but now it had a skin that bore a strong resemblance to a syrup-drenched stack of pancakes. To make matters worse, when I stored the finished baidarka in an unheated warehouse in the middle of winter, the nylon went slack with the cold and was as wrinkled as a raisin. During the summer the skin smoothed itself, but as soon as I put it in the water it cooled off and got all wavy again.

My baidarka,weighing just 42 lbs, sits lightly on the water. On this cold winter day the deck shows a bit of the waviness that plagued the skin for years.

I haven’t been kayaking since last summer, but I was able to get the baidarka up to 7 knots. I did speed trials with scores of sea kayaks while I was the editor of Sea Kayaker magazine and there were only a handful that were as fast. Here I’m using a carbon-fiber wing paddle. The Aleut paddle I made is in storage and I’m not as adept with it as I am with the wing.

I didn’t paddle the boat much at all until about three years after completing it. Fortunately, the skin got tighter with time and the color became darker and richer and concealed the drips. I began to take the baidarka out and bit by bit learned how the Aleut design performed. It was clearly fast, especially given its 16′ 8-1/2″ length. I didn’t have a good way to measure its speed, but when I got a GPS years later, I found I could hit 7.2 knots in a sprint. Zimmerly’s plans note the theoretical top speed is 4.9 knots. When I took the baidarka out for the photos here, I hadn’t been kayaking for months, but I still managed to record 7 knots on the GPS.

In wind, the fairly low profile keeps the baidarka from getting blown around and the long bow counters weathercocking. The slender lower bow cuts cleanly through smooth and rippled water, and the broad upper bow provides lift in oncoming waves. In a following sea, the buoyancy above the waterline created by the spread of the gunwales keeps the stern from being swallowed up by waves. It rises instead and you can feel the waves pushing the baidarka forward. It’s a great boost for starting a sprint to get surfing.

After I finished my baidarka I stumbled upon a hidden key to an Aleut baidarka’s speed. In 1805, Urey Lisiansky, a Russian sea captain traveled 300 miles in a baidarka and wrote: “At first I disliked these leathern canoes on account of their bending elasticity in the water, but when accustomed to them, I thought it rather pleasant than otherwise.” I doubt my baidarka is as flexible as the original Lowie specimen. The urethane soaked through the nylon and bonded it to the frame, so the whole structure is quite rigid. The skin of the original baidarka wouldn’t have restricted the frame’s movement and the flexing would have allowed the frame to conform slightly to the shape of the waves as well as soften the impacts of rough water. Kayakers who have both folding kayaks and rigid molded kayaks know that the folders have a speed advantage when the going gets rough.

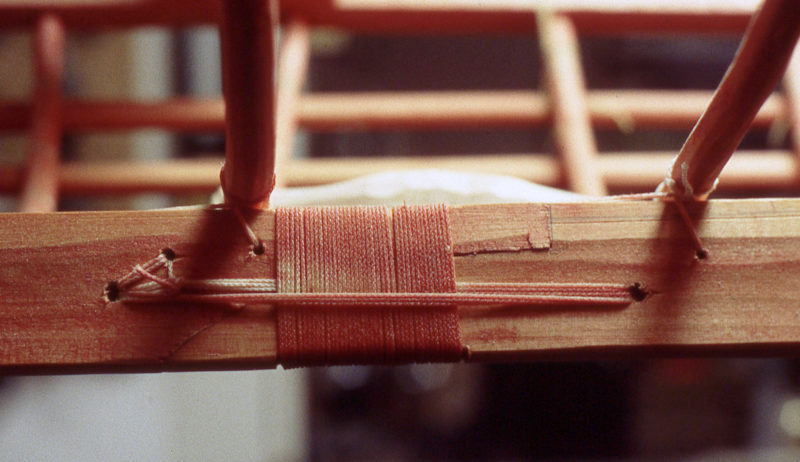

There are two joints like this in the keel. They seem designed to let the ends of the baidarka curve down around a wave lifting the middle of the hull, yet support the paddler over a trough.

The keel of the Lowie baidarka is made up of three pieces and the joints between them are shaped like the moldings on drop-leave tables—a mating quarter-round with a small vertical butt joint at the top. The way the keel is constructed, the ends of the baidarka can move slightly to wrap around the crest of a wave, but resist sagging into a trough.

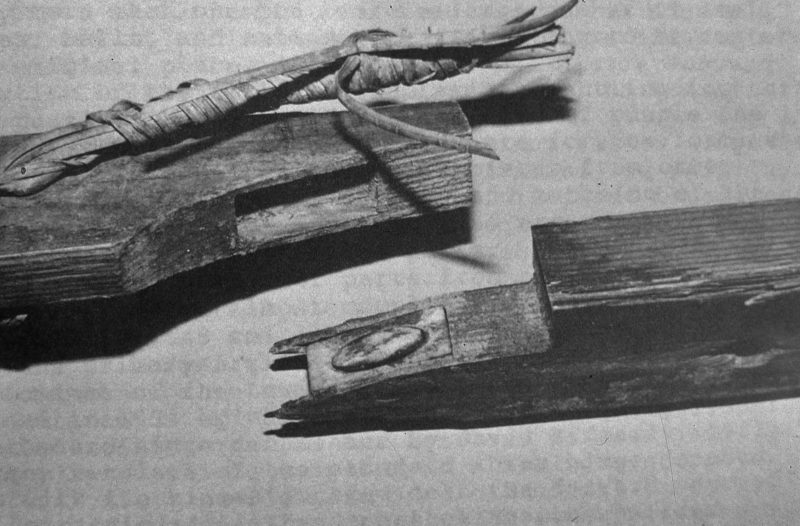

In this damaged museum specimen, the bone bearings hidden inside a keel joint are visible.

The joints in the Lowie baidarka may be concealing some interesting bone bearings called kostochki. Joe Lubischer, a Canadian graduate student in anthropology and a fellow kayaker, once mentioned to me that the literature on baidarkas suggested the existence of these bearings but none had been discovered in the museum specimens he knew of. A few months earlier I had just happened to see a bunch of kostochki at the Burke Museum on the University of Washington campus. I had gone there to see what I might find in their collection related to baidarkas and was allowed to see a baidarka that had been collected in and shipped from Alaska quite a while ago. To get the unskinned frame to fit into a reasonably sized shipping crate, someone had sawn it into pieces. Unfortunate for the kayak, but lucky for me, and for Joe, that all of the bone bearings were accessible.

The kostochki in the keel joints were elliptical bone bearings cradled in matching recesses carved into bone rectangles which were set into mortices on either side of the curved part of the joint. The allowed a bit of longitudinal movement, but no lateral movement. There were also rectangular strips of bone let into the contact surfaces between the deck ridges and the deck beams. John Heath believed the principle function of all of the various kostochki was to prevent wood surfaces in contact with each other from wearing away over time. The bone could endure the abrasion and keep the joints from getting progressively looser inside of their lashings.

A few years later Joe and I, along with George Dyson, author of the book Baidarka, studied a baidarka on loan from a Russian museum. It was collected in Unalaska in 1826. With a veterinarian’s X-ray machine, we made images of the joints and the films revealed the kostochki inside of them. If I had known about the bone parts when I built my baidarka I would have made them, even if all that work would be hidden away, just to experience a little connection with long-forgotten baidarka builders.

I suspect that the kayak I designed for myself four decades ago will be the only kayak I will ever design. I suppose I’d take some pride and pleasure in coming up with something that performed well, but nothing I could do would fill me with a sense of wonder as the genius that lies waiting to be discovered in kayaks from the past.![]()

In 1992, I had the great fortune to hear George Dyson speak on the indigenous Aleutian baidarka design at the L. L. Bean Kayak Symposium held at the Maine Maritime Academy in Castine Maine. In his physically animated three-hour presentation, Mr. Dyson described how this ancient technology was far ahead of any current knowledge of the design and function of solo sea craft. He eloquently explained how the unusual hull shape and strange stem forms were tailored to the task and environment of the Bering Sea.

I had been paddling whitewater for more than 10 years at the time and I immediately noticed the high volume fullness of the baidarka hull design carried to the stems. Then current white water boat designs had evolved in this direction to ride over big waves instead of punching into them as happened with fine stems and traditional hull shapes.

Mr. Dyson quoted historical accounts of European explorers of the Bering Sea sailing downwind and, being overtaken and left behind by Aleuts in their baidarka kayaks. Dyson wondered as did others, where did this amazing speed come from? Many have speculated about the baidarka design as the sole source, and missed the obvious. Like another means of traveling over water, snow shoes and skis look different but it’s the open mountain sides that make skis fast, not just the shape and design difference. So it is with the mountains of water, in the seas surrounding the Aleutian Islands, that provide the secret of the baidarka speed. The average summer sea heights around the Aleutians are 8 to 12 feet. The winter wave heights are 15 to 25 feet. Seas don’t freeze in this area. The Aleut baidarka is designed to surf these mountains, so paddlers can conserve energy and travel great distances. This style of surfing is not for the fun of following the incoming wave to shore, but to travel far and fast on mountains of water. Anyone who has seen the “Deadliest Catch” television program knows what the Bering Seas huge waves look like!

Indigenous kayakers in other parts of the Arctic had the skills to paddle rough seas and large waves, but the Aleut did it routinely and year round. And after paddling full time for generation after generation they probably had water reading skills we cannot imagine. The fist time Olympic kayak sprint champion Greg Barton paddled with the South African surf ski champ Oscar Chalupsky on the open ocean and he was left far behind because Greg didn’t have the wave reading skills to surf instead of just paddle hard.

For more in-depth search or follow these links

Anthropologist in the Attic: Aleutian Ikyax aka Baidarka

The Aleut Kayak: How Aleut Technology Shaped History

Lessons From Ancients Who Plied the Waves – The New York Times

Baidarka – Kayak Building BB

Baidarka – Guillemot Kayaks site

Baidarka – Kayak Building BB

Kayak Building BB

Greg Barton

Thanks, Rob, for adding to the understanding of traditional Aleut baidarkas and how they were used. The native paddlers were doubtless skilled at reading the waves and using them to advantage. And as one might expect, they grew very strong relying on paddling for their livelihood and survival. In Bioarchaeology, author Clark Spencer Larson writes:

Populations inhabiting the Aleutian Islands, Alaska…led physically demanding lifestyles. An especially demanding task was kayaking on the open ocean. This activity underlies extreme external robusticity of Aleut humeri…. Comparisons of Aleuts with other populations in humerus torsional rigidity reveal that these subarctic peoples surpass values derived from a range of modern groups. These elevated levels of bone rigidity reflect intensive mechanical loading of the upper limb, especially in use of the arms in paddling of watercraft on the open ocean.

UK Kayaker here,

I read that traditionally built hull flexibility aids/improves speed, but not found a theory as to why.

Can anyone help? How flexible is enough, and then…too much?

In rough water, a kayak’s flexibility reduces pounding and slapping by slightly conforming to the shapes of the waves. In the kayaks that I’ve built in the traditional manner I can feel the frames flexing and the ride is not as jarring as that of a modern composite kayak. I don’t know of a way to quantify the flexibility. One of my experienced kayaking friends used to be part of a group paddling folding kayaks, which are also flexible. He recalls that in flat water, the folding kayaks weren’t as fast as composite kayaks but in rough water they were faster.

This is all fascinating to me. I built a copy of the same boat about 8 years ago, and indeed it is a pleasure to paddle. Light and fast with no need of carbon fiber or fancy molds or anything hi-tech at all. And my favorite paddle is a copy of the very one that was measured with this boat. The Aleuts had a lot of things very well sorted out. Greenland paddles are very popular these days, but I find some of the Aleutian designs even more effective for the kind of paddling most of us do.

Thank you! The timing of your Baidarka article is a happy one for me as I’m currently stripping a Baidarka hull for a friend and whitewater buddy.

Reviewing the Baidarka stories and sources has refreshed my appreciation for the complex beauty of this design. After working on my interpretation of the Baidarka and building versions for 28 years, I’m still excited and amazed by the hull form every time I build one.

When I told my friend about the historical accounts of Aleuts passing sailing ships he replied without hesitation, “They were surfing.” Only another person with years of dynamic water experience could see so clearly how paddler, boat, and sea conditions equaled a speed no European had ever seen at that time!

Thank you Rob! I took delivery of one of Rob’s strip built baidarka’s in October of ’99. I love this boat and can still paddle it at 79 years of age. While surfing off Tybee Island a while ago I had a collision with another kayak (my fault) and the bow piece came off. The boat was still water tight and I was able to reattach the piece later. With my limited knowledge and abilities I fine that my baidarka is extremely difficult to correct in the surf after it starts to turn. Other than that it’s fast and beautiful. I use a Greenland paddle for propulsion.

Chris,

A little more than 20 years ago I too, was fired up by baidarkas, only in my case it was after reading George Dysons’ book.

I went on to build the 18’ boat in the back of the book, only I used wood instead of aluminum for the structural pieces (re-sized to give equivalent strength) and made it folding, so that I could take it apart and put it on a plane. Its first big trip was after I packed it up, flew with it up to Haida Gwaii and paddled there for nearly a month in 2001.

The baidarka was within a pound of the same weight and an inch of the same length as my previous rigid wood kayak but I found that, with the same touring load, I could maintain an all-day pace a knot faster, with the same effort.

It remains my favorite kayak.

Chris,

Of course I knew you were an expert on canoes. Thank you for all your advice and knowledge. This article is absolutely fascinating.

Thank you!

Chris

This is a fascinating and well-written article. The description of the Aleut design features was precise, descriptive, yet easy to understand. Thank you.

I had the pleasure of working with you at Sea Kayaker ten years ago as you coached me through writing my only article. Your choice to title it “COLD AND ALONE ON AN ICY RIVER” was spot on.

See you on the water.

I had the great luck of owning Rob Macks’ first wood-strip baidarka many (many) years ago. I paddled it around Massachusetts and Maine for years, including a couple of the early Blackburn Challenge races around Cape Ann at Gloucester. People in their carbon racing kayaks were astounded at the speed of my varnished, wood strip boat, especially one year with strong winds and heavy seas. And best of all, Rob built a heart-stoppingly beautiful boat.

And I had the great luck to to have a small-boat impresario, Harvey Schwartz, come to me to build him a Greenland-style kayak. I had just returned from the 1992 L. L. Bean Kayak Symposium and when I told him about George Dyson’s baidarka lecture, he urged me to build the first hardshell version baidarka for him. At first I told Harvey, no, I don’t know how to do it. Figuring out how to translate those unusual bow and stern stems of the baidarka from skin and frame to stripper construction was daunting task. But Harvey had confidence in me. He gave me the push that made it happen. If Harvey had not come along at the right time my stripper baidarkas might have remained a dream.

Chris,

I’m hoping to finish my Greenland SOF built per your book this winter. I’m already chomping at the bit to build a baidarka. Has anyone written a book or a paper about the bone bearings found in various baidarkas? I’d love to see pics of the X-Rays, a pic of the bearings and the bone receptacles they sat in, etc.

Joe Lubischer wrote about the kostochki and published a short booklet about them: The Baidarka as a Living Vessel: On the Mysteries of the Aleut Kayak Builders. Joe also wrote a chapter— “The baidarka as a living vessel: the ‘bones’ in the joints”— in Eugene Arima’s book: Contributions to Kayak Studies. You may be able to find used copies listed for sale on the web.