Several of the boats I’ve built have required carts to get them from the launch-site parking lot to the water, and while the carts I’ve built have all worked well enough to carry the boats they’re made for, they haven’t been compact enough to stow neatly when it’s time for the boats to carry them. While there are, of course, many good folding and take-apart boat carts on the market, I prefer to make my own equipment—not only for the pleasure of designing and making things, but also to save money.

The frames of the commercial carts are usually made of aluminum and molded plastic, and the designs don’t lend themselves to homemade wooden interpretations, so none of them were of much use in my quest to build a homemade cart that can carry the boat and take up little space on board.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThe cart for the sneakbox easily managed the 140-lb boat and the gear carried aboard it.

With the cart secured amidships under the 80-lb canoe, I have very little weight to lift and can guide the canoe with a loose grip.

With my most recent carts, made for my sneakbox and lapstrake canoe, I devised a simple design for a take-apart frame made of four interlocking pieces of 3/4″ plywood. I added a pair of hand-truck wheels—with pneumatic tires—that I found on a curbside with a “Free” sign on them. If you’re not as lucky, similar 10″ pneumatic hand-truck wheels can be purchased online at various sites, including Harbor Freight for $9 apiece. The wheels require a 5/8″ axle, and a length of zinc-plated 5/8″ steel rod costs less than $20 at most hardware stores and home improvement centers.

The interlocking pieces of plywood have notches cut in them for quick assembly of the frames. The crosspieces are scribed to fit the hull close to amidships; having the cart take the load makes pulling or pushing the boat by hand much easier. I deliberated about the axle running through the 3/4″ plywood without any reinforcement to provide more strength and durability, but the axle doesn’t spin in the plywood—the wheels have bearings—so any wear is likely to be very slow. If the axle gets too loose in the hole, I can add pieces of hardwood with freshly drilled holes. The axle itself needs a hole in each end for hitch-pin retainer clips. The only trick to drilling the steel rod, either with a drill press or a hand-held drill, is to make a small divot in the rod with a center punch. The dimple will keep the drill bit from skating off target. The holes in the plywood frame are for rope or a webbing strap to secure the cart to the boat. The lines or straps must be pulled very tight to keep the cart from tripping if the wheels meet an object too tall to roll over smoothly. Foam pipe insulation is ideal for padding; it comes with a slit along one side that is easily pulled apart to make an opening for the edge of the plywood.

I used a compass to scribe the bottom contour of my lapstrake canoe on a scrap of plywood.

A flexible plastic batten shaped a curve to fit one half of the scribed line.

The half pattern cut from the scrap serves as the template to mark the contour on the cart’s transverse pieces.

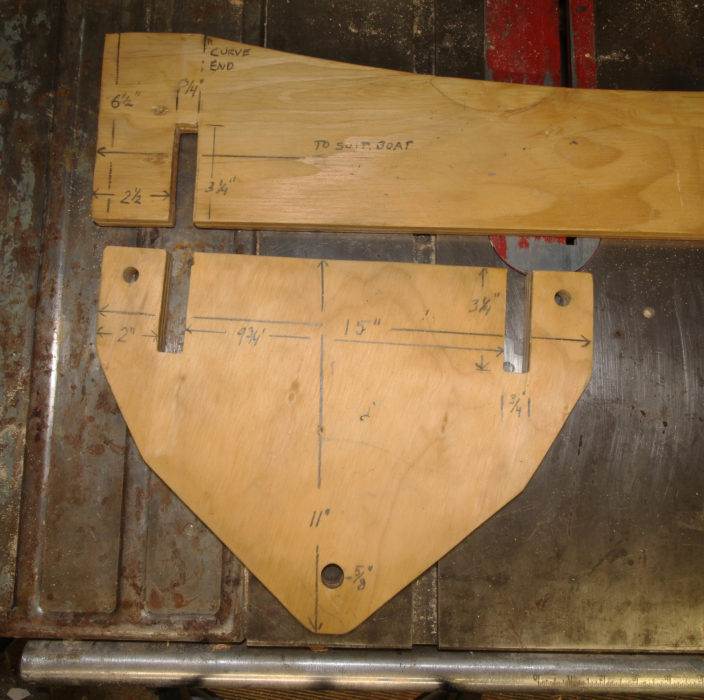

These are the dimensions I used for the sneakbox cart. The patterns accommodate 10″ pneumatic hand-truck wheels.

There’s an advantage to a cart that comes apart into separate components. The pieces can be stowed in small spaces. All of the cart pieces for the canoe fit under the aft deck with room to spare.

Tie-down straps are well-suited for the cart. The 12-footers are long enough for the canoe and the sneakbox. The pivoting kickstand (to the left of the tire) greatly simplifies loading the cart by holding it nearly upright, ready for the hull to settle on it.

On firm sand, the tires have a wide enough footprint to keep from sinking.

Soft sand is a bit harder to negotiate, especially on the uphill run from the water to the parking lot.

The easiest way to move the canoe uphill in the soft sand was to loop some line about the bow handle and face the boat, holding the line with both hands. Rather than muscle the canoe forward, I just leaned away from it and let my weight do the work. A tug with both arms would continue to move the boat. After taking a step back and planting both feet, I tugged again. The method, a lot like a dog tugging on a rope toy with all four paws planted, was surprisingly effective.

If you have more than one boat that requires a cart, you can make additional front and back transverse pieces and axles to fit each boat. I made crosspieces to adapt to fit both the 140-lb sneakbox and the 80-lb lapstrake decked canoe. The wheels and the side pieces of plywood serve both boats.

For each cart, the disassembled plywood frame pieces make a stack just 2-1/4″ thick and the wheels, taken individually, are compact enough to be tucked away in small spaces on board.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Magazine.

You can share your tips and tricks of the trade with other Small Boats Magazine readers by sending us an email.

“I used a compass to scribe the bottom contour of my lapstrake canoe on a scrap of plywood.” — can you elaborate? I’m not clear about that step. Nice article, by the way 🙂

Here’s a picture of scribing the contour of my sneakbox’s foredeck:

The compass is held vertically and as the leg on the boat follows the contour, the pencil makes a tracing.

Why scribe on a scrap, copy and fair with a batten, and use that to make a template? Why not scribe directly on the transverse piece and fair it?

It would be difficult to orient the transverse piece on the hull with its ends and the curve in the proper relationship.

I think I’m missing something. How is it easier to scribe on a scrap than scribe on the transverse piece? Aren’t they both pieces of plywood, more or less the same size?

Thank you for writing back.

You can certainly try scribing the curve on the transverse piece. While the concept may be easy to visualize, it’s a different story as a practical matter. I found it difficult to set a piece of plywood on the hull and hold it centered, upright, level, and square to the hull’s centerline and then scribe the curve to a measured length. I was doing the task by myself; an extra pair of hands would make it easier.

Thank you. I’m ready to go at it now.

Thanks for sharing. Looking forward to more.

Finally, a use for the weird little off-cuts of ply from our construction project!

An improvement on my 2×10 and 2×4 cart. I use swimming noodles longitudinally. I will make this with exchangeable cross-wise members to fit my kayak, cedar canvas canoe, and Walker Bay soap dish. Heck, I could make one for my Laser, which I now row more often than I sail. I will send plans of my rowing rig, made of hockey sticks. I may make a new one out of carbon fibre or aluminum hockey sticks. Who knew that wood hockey sticks are not marine grade?

Does the kickstand swing out of the way into a storage position? Does anything hold it in position when it’s in use?

Great concept and design!

The wooden kickstand is simply screwed to the side of the cart’s frame, tight enough for a friction fit so it stays where it is put. The cart is positioned so the kickstand will be on the back side. When the boat is set in place, the cart comes upright, raising the kickstand enough to clear hard ground. The kickstand will pivot if it drags in sand or hits an obstruction.

Cool cart, Chris!

How bout instead of multiple cross panels for multiple boats, finicky cut with a compass (great trick by the way!), plus pool noodle foam, scoop that hollow deeper and sling it with scrap carpet? Carpet strips are pretty easy to get ifn you have a box knife: even if a house has an alarm you can be in and out in less than a minute.