A summer of sailing seemed like the perfect solution to a global pandemic. What better quarantine than a few weeks alone outdoors, aboard an open boat designed for long-distance cruising? As classrooms emptied overnight and the school year ground to a halt online, I established a nightly ritual of studying charts after the last papers were graded: Georgian Bay, Lake of the Woods, Lake Nipigon, the Pukwaska. In early May, my wife helped me wrestle the boat upside-down atop its trailer for a partial refit. Three coats of paint, inside and out; a few sessions of oiling thwarts, spars, and gunwales; a length of brass half-oval screwed to the stem to protect the forefoot; a new becket block for the downhaul—these small chores offered a welcome diversion to rising case counts, mortality rates, and other grim portents of the looming disaster.

By mid-June I was more than ready, but closed borders had thrown a wrench in the gears before I could even get started. There’d be no trip to the Canadian side of the Great Lakes this summer—no trips to the Canadian side of anything. Even travel within the U.S. seemed like a dubious proposition. Like Huck Finn, I wanted to “light out for the Territory,” at least for a while, but I couldn’t even make it out of my own backyard. I was thoroughly landlocked.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

Landlocked. Except…Wisconsin is surrounded by water on three sides. The U.S. side of the Great Lakes was inaccessible for now—the Apostle Islands and Isle Royale, the obvious choices, were closed to overnight visitors, and Green Bay was a COVID-19 hot spot—but the Mississippi River offered a West Coast of sorts. Here the dramatic bluffs and coulees of the Driftless Area—land untouched by the last Ice Age—lined the river for more than 250 miles along the Minnesota–Wisconsin border. Better yet, the broad flood plain was largely uninhabited, offering plenty of space for a small boat to pull in for the night undisturbed. Suddenly I could envision weeks of cruising possibilities, all of them starting just an hour or so from home. I could wander the sloughs and back channels by sail and oar, exploring the swamps and tributary streams, the islands and sand bars, and all the marshy backwaters that bordered the big river—coastal cruising, inland style. I ordered a complete set of charts for the Upper Mississippi and started packing my gear.

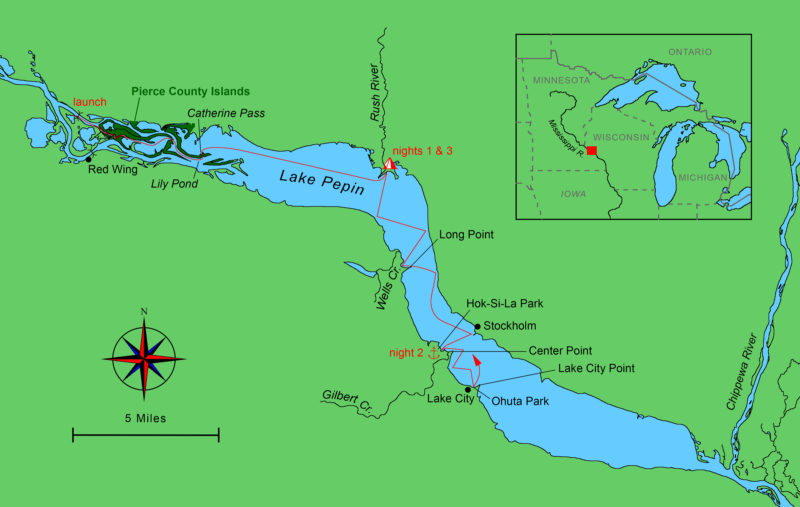

I put in at a public ramp on an island just off the Wisconsin side, 45 miles southeast of Minneapolis: not quite the very beginning of the Mississippi River’s run along the Wisconsin border, but close enough. Besides, I needed a landing that offered overnight parking, and this one fit the bill. Better yet, just a half mile from the ramp, the river spread out into a sprawling swirl of ropy islands that stretched for five miles downstream. After loading the boat with two weeks’ worth of food and gear—this would be a quarantine cruise, with no stops to resupply—I stowed the sailing rig and headed downstream under oars.

Even at my usual leisurely rowing pace—between 2 and 3 knots, but probably closer to 2—it took me less than 10 minutes to reach the islands. Almost immediately the riverbanks drew close on each side, offering impenetrable walls of midsummer greenery. Dead branches and even entire tree trunks rose from the water here and there like bleached bones, almost blocking the channel completely in a few places. The sound of police sirens in nearby Red Wing, Minnesota, drifted faintly across the water as I rowed, but the city itself was invisible; I could have been days from home, lost in a world of swampy forests and lowlands. Sloughs and side channels crossed and re-crossed each other at every bend, overhanging with oaks and cottonwoods, forming a network of overgrown canals with a vaguely post-apocalyptic feel—Venice, maybe, a few hundred years after its human inhabitants had fled. A belted kingfisher flashed by in a swooping rush along the bank on river right as I rowed past, its chattering call echoing behind me. It was the only traffic I encountered.

A thousand yards away on the Minnesota side, I knew, the river’s main navigation channel was busy with barges and powerboats hurrying along the foot of Red Wing’s tall sandstone bluffs. Nine hundred yards in the opposite direction, the wide Wisconsin Channel hugged the northern shore, offering a clear route for recreational power boats. But here in the center of the Pierce County Islands State Natural Area, my only company was the kingfisher I had seen earlier—and now, a pair of bald eagles that repeatedly fled downstream at my approach, only to be startled from each new perch a few minutes later as I rowed past again. It was a game I was familiar with, but one I associated with blue herons, on smaller rivers; this was the first time I’d played it with eagles. After a few more intermittent retreats downstream, they finally got tired of my interruptions and flew off for good, leaving me alone again in the winding back channels.

After 90 minutes or so, my winding route brought me to the edge of the islands at Lily Pond, within sight of the main traffic channel. I pulled onto a sandy beach at river left to stretch my legs. The day was overcast, and not too hot—perfect weather for rowing—but I didn’t want to pass up an opportunity for a brief stop ashore. Half a mile away, close in along the Minnesota shore, a nine-barge tow pushed past, just visible behind the long thin island that bordered the main channel. From my place on the riverbank, the towboat’s powerful diesel was barely audible. Eight hundred feet of boat and barges running a river barely 800′ wide, coming into a hairpin curve 3 miles long—a good reason for a small sail-and-oar boat to stay in the sloughs and backwaters.

Photographs and video by the author

Photographs and video by the authorThe narrow channel into Catherine Pass looks like a detour from the direct route into Lake Pepin. In fact, a huge expanse of shoaling sandbars blocks the northern reaches of the lake, making Catherine Pass the better option.

After another hour of rowing and dawdling, I reached the eastern edge of the islands and slipped through a narrow passage into Catherine Pass at the upper reaches of Lake Pepin. Leaving the oars trailing in the mud-brown water as the slow current carried the boat downstream, I stood up to see over the tall reeds that lined the shore—the small-boat equivalent of posting a lookout at the masthead. There was open water ahead, and the first faint stirrings of a breeze rippling the water’s surface. The boat drifted past the mudflats on each side of the pass, each as wide as a city street, and coasted out into the lake in a silence broken only by the cry of seagulls circling overhead.

I rowed past the shoals at the mouth of Catherine Pass, rounded the corner into Lake Pepin, and stepped the mast, lifting it into the partner and tapping a couple of wedges in place. A few more moments later, I had the standing-lug mainsail up, a simple operation in such calm conditions. I tightened the downhaul, lowered the centerboard and rudder, stowed the oars aboard, and trimmed the sheet for a close reach. Once the sail was drawing well, I tied the sheet off to an oarlock with a slippery hitch and settled in.

At the upper end of Lake Pepin, the steep and exposed shoreline limits options for shelter in a real blow. In 1890, the 135’ excursion boat SEA WING overturned and sank just a few miles downstream, with the loss of 98 people. Fortunately, I enjoyed better weather on my passage to the Rush River.

Lake Pepin forms an elongated backwards S shape on the map—east, then south, and finally southeast again—running from Red Wing, Minnesota, to the mouth of Wisconsin’s Chippewa River 20 miles downstream. Here a broad sandy delta pours into the Mississippi, sediment from the 6,000 square miles drained by the Chippewa River in its 180-mile run from northwestern Wisconsin, forming the natural dam that created Lake Pepin. Elsewhere, the Upper Mississippi is drastically undersized for the valley through which it flows, which was cut by the much larger Glacial River Warren 10,000 years ago. Here in Lake Pepin, water fills the ancient flood plain entirely, forming a channel 2 miles wide, hemmed in by forested bluffs topped by 60’ sandstone cliffs.

Each tributary stream along Lake Pepin forms its own delta, and I was counting on one of these tributary deltas, at Wisconsin’s Rush River, to provide shelter for the night. Luck was with me. The faint afternoon breeze grew stronger, and veered toward the south, letting me steer a direct course toward my destination. With the sheet tied off and my line-and-bungee autopilot steering, all I had to do was enjoy the ride. After a 6-mile crossing that barely required me to touch the tiller or the sheet, I was closing in on the long sandspit at the mouth of the Rush River, just an hour ahead of sunset.

I cut the corner a little too closely. The boat ground to a gentle halt just off the spit, on a shoal that extended a bit farther than I had expected past the line of wading gulls I had been using for a channel marker. With the sail still drawing, I raised the board and rudder, hopped out in shin-deep water, and waded alongside for 10 yards before climbing back aboard to continue up the Rush River.

Wisconsin’s Rush River is, by all reports, a prime trout stream. Lacking the requisite fishing gear, permits, skills, and, more importantly, having no inclination to work for my supper, I had to be content with a carry-out pizza from Pizza Hut that I had stowed aboard.

I was running downwind against the current now, making slow but steady progress. The banks closed in, forming tangled green walls on each side, leaving just enough wind to keep the boat moving. I eventually pulled up on the eastern bank, alongside a low sandy ridge shaded by widely-spaced oaks and cottonwoods. Tying off the painter to a convenient branch, I carried my bags ashore. Expecting mosquitoes—I always expect them, and am rarely disappointed—I set up my tent on the flat sandy ridgetop under a massive oak tree and laid out my sleeping gear inside. Then, ready for a quiet evening ashore, I spent an hour or two wandering along the sandy beaches of the delta’s eastern shore.

The next morning, I packed up the tent and returned to the beach for a preview of the day’s route down Lake Pepin. Even this early in the day, a blustery southerly breeze was blowing, and knee-high waves were rolling up the lakeside beaches. Yesterday’s south wind had served perfectly for my generally eastward route. Today, as I turned the corner to follow Lake Pepin’s backward S to the south, that same breeze, stronger now, would be a stiff headwind.

As usual, I skipped breakfast to set out early, but then squandered my head start by rowing up the Rush River for a mile or so, until a house-sized pile-up of fallen trees blocked the stream from bank to bank, forcing me to turn back. Another kingfisher showed a flicker of black and white as it swooped across the stream, but only the quiet dip of the oars, stroke after stroke, broke the morning stillness. Soon enough I was back at the river mouth. My upstream diversion had cost me almost an hour, but I didn’t feel any regret about that. Diversion was the whole point of the trip.

The wind was still blowing when I reached open water, and still from the south. I had guessed that the region’s prevailing westerlies would carry me easily to the mouth of the Chippewa River, and I had guessed wrong. At least the broad channel, 2 miles wide, would provide ample sea room, with no need for short-tacking. It was a bright blue-sky morning, and perfect sailing. Sunlight glinted off the waves as the boat bumped along to windward, with a spattering of cool spray every now and then. With an open boat, an open calendar, and room to wander, I wasn’t going to complain about a few headwinds.

The sandy banks of the Rush River transition to thick mud along the water’s edge—a fact I discovered when I set foot on shore and sank in above my ankles. Still, the river delta provided a welcome sheltered mooring spot along Lake Pepin’s exposed shoreline.

A couple of hours later, after 3 miles of progress earned by 6 miles of blustery windward sailing in three long tacks, I was ready for a break. I sailed into the lee of Long Point on the Minnesota shore, where tiny Wells Creek had dumped enough sand to create a long spit that protruded from the river in an elegantly symmetrical dagger point. It looked like a perfect place to wait out the wind, in the lee of the spit’s low wooded ridge, but I barely had time to brail up the rig and drag the boat onto shore before I saw a dozen powerboats headed for the beach in close formation. Radios blaring, people shouting, outboards roaring—a typically overbearing Midwestern cheerfulness sustained by an excess of cheap beer, and painfully lacking in self-awareness. I wasn’t sure I could endure it all with any measure of grace. I took a brief look around me—the pale fine-grained sand of the beach, the network of shady trails running through the delta’s swampy woodlands, the marshy backwater I hadn’t even begun to explore—and re-launched the boat. After rowing a few yards offshore, I deployed the sail again. I was 100 yards out by the time the powerboats hit the beach. My quarantine would remain intact.

A narrow-beamed pulling boat isn’t at its happiest sailing to windward, but I kept bashing my way southward under full mainsail without too much trouble. It was slow going now, and not particularly restful, but it wasn’t until late afternoon that I started thinking about reefing, or getting off the water entirely. I made a final tack just outside the marina breakwater at Stockholm, Wisconsin, and headed back to the Minnesota side. Hok-Si-La Park, just upstream of Lake City at Lake Pepin’s Central Point, offered waterside camping. Or it had, before the pandemic started shutting down options. I wasn’t sure what I’d find now.

Although it’s essentially a narrow pulling boat, Don Kurylko’s Alaska does well to windward under full mainsail. Once it really breezes up, though, the shorter luff of the reefed mainsail doesn’t perform as well. Fortunately, I set out from the Rush River with a perfect breeze—not too weak, not too strong.

I reached the sheltered water on the north side of Central Point and coasted into a quiet bay at the mouth of Gilbert Creek—a creek too shallow even for my boat’s 8″ draft, and blocked by a large flock of geese that didn’t appear eager to give way. I dropped the rig, pulled out the oars for the final approach, and anchored 100 yards west of the creek, taking a line from the transom to a driftwood log on the beach. Despite the day’s unimpressive run—only 7 miles of real progress—I was ready to be ashore for the rest of the day.

Once the rig was stowed, I climbed the bluff above the bay to find Hok-Si-La’s campgrounds empty. There were a few cars in the day-use parking lot, and a few widely spaced families on the main swimming beach, but no one at all in the campground above my anchorage. A sign posted on the locked restroom building proclaimed that overnight camping was closed until further notice. I walked along the shaded campground loop again, past dozens of empty campsites. Not a single car, or a single camper. But on the edge of the campground loop above the lake, just a two-minute climb from the beach, I found a pit toilet still open. Good enough for me.

The morning sun woke me early at my unofficial anchorage at Hok-Si-La City Park, near the entrance of tiny Wells Creek. The park’s swimming beach and boat ramp are out of sight, just around the headland.

I returned to the boat and set up the platform for sleeping aboard—anchoring out would keep me within the letter of the law. The geese left Gilbert Creek and paddled by 30 yards offshore, then took flight in a sudden honking flurry to head off across the lake in a straggling V. A long-legged heron swooped in to stalk the shallows at the mouth of the creek, while a pair of eagles rode the thermals along the bluffs high above.

Before long, I had finished my onboard sleeping arrangements—platform, tent, and gear—but it would be hours before I needed them. The strong southerly breeze was reduced to a quiet stirring of leaves along the edge of the beach, and the warm sun felt good after a long day of beating to windward. I carried my folding camp chair ashore—a recent concession to comfort—and spent the afternoon reading in the shade of a tall cottonwood while the heron speared frogs from the creek. Out on the open water of Lake Pepin, keelboats and cabin cruisers bashed their way through the whitecaps. I was perfectly content to be ashore.

The next morning, a fierce southeasterly was blowing, even stronger than the day before. Out on the open water beyond Center Point, the waves were bigger than ever. Any upwind progress today would be slow, wet, and cold—stupidly so, in fact. But I couldn’t quite bring myself to give up on the trip and turn back to the car just yet, even though—secretly—I knew that I would end up doing exactly that. But I told myself I’d sail up to Lake City before deciding, a 2-mile test run.

I hoisted the sail, rowed out into the wind, and spent an hour beating into a whitecapping chop, making slow progress—and the wind seemed to be getting stronger, backing just enough to remain stubbornly opposed to my intentions. Just off the beach at Lake City’s Ohuta Park, in the lee of Lake City Point, I dropped the sail and set an anchor off the bow. Then I rowed in to take a line ashore from the stern, leaving the boat afloat in knee-deep water.

Once the boat was squared away, I walked to a bench overlooking the lake to enjoy a sandwich for breakfast. The wind was roaring, the open water all whitecaps and rolling waves. The mouth of the Chippewa River, with its islands and backwaters, was still 8 miles away, dead to windward. Enough was enough. I felt no more than a vague twinge of disappointment. Or, to be completely honest—not even that.

I returned to the boat, untied the shore line, climbed aboard, and drifted out over the anchor, 20 yards off the beach. I was coiling lines and tidying up when I heard someone calling me.

“Sir?” a quiet voice said. I didn’t see anyone. “Sir? Help, sir.”

A few yards out, a young boy was treading water—barely—with his chin just above the surface. Then he ducked under until the top of his head was all that showed for a moment before bobbing slowly back up. “Sir? Can you help me, sir?” he called again.

It wasn’t the least bit dramatic—but then, I knew from my experience as a lifeguard that real drownings rarely are. Moving quickly but calmly, I tossed one end of a line to the boy and pulled him over to me. With the boat’s low freeboard, he was able to pull himself aboard without much trouble. I rowed him to shore and left him with his mother, who had been watching helplessly from the beach while her son nearly drowned. A non-swimmer, he had waded out to the edge of the buoyed swimming area and lost his footing, drifting out into water well over his head.

Headwinds or not, I was glad I had decided to sail down to Lake City before turning back. The boy’s mother was even happier—pandemic or not, I wasn’t able to avoid several hugs and a series of tearful thank-yous. As I rowed away, she was escorting the boy back to their car—the only one in the lot—toweling his hair dry, hugging him over and over, and keeping up a running commentary that was more relief than anger: “What were you thinking? What on earth were you thinking? If that man hadn’t been there in his boat.…”

Smiling to myself at the thought of being known forever as that man, I rowed off the beach, tied a double reef in the mainsail, and stowed the oars. I’d come back another time to explore the Chippewa River delta. Meanwhile, these conditions were just what I needed to take me back to the Rush River at speed. Too much speed, maybe, but I was going to give it a go. Still smiling, I hoisted the sail, turned off the wind, and moved aft to put my weight where it was needed for downwind sailing.

Although it’s essentially a narrow pulling boat, Don Kurylko’s Alaska does well to windward under full mainsail. Once it really breezes up, though, the shorter luff of the reefed mainsail doesn’t perform as well. Fortunately, I set out from the Rush River with a perfect breeze—not too weak, not too strong.

White-topped waves rolled past, setting the boat pitching and rolling as we slowly steadied on our northward course. The sky overhead was gray and filled with rolling clouds. I eased the sheet for a broad reach on the starboard tack and felt the boat take off with a surging rush of speed, a sustained acceleration that continued until cold spray was flying past in tall rooster tails that reached well over my head. I steered for a tall headland 3 miles upriver on the Wisconsin side, a course far enough off the wind to avoid an unexpected and possibly disastrous jibe, and settled in for the ride.

The boat sailed northward in a wild rush between white curtains of spray, yawing slightly back and forth atop each passing wave, surfing and heeling and settling as wave after wave passed beneath the hull. It was a wet ride. I pulled on my rain jacket one arm at a time, managing the sheet and tiller carefully. Still, what would have been desperate sailing under full sail was merely exhilarating now; under the double-reefed main I had perfect control.

Five miles down the lake, my northward run halfway over, a foiling kiteboarder swept by at 20 miles per hour—the only other sailor in sight.

“Sweet!” he shouted, and then he was gone.

I knew exactly what he meant.

On my return journey, I camped again at the mouth of the Rush River. I tied up alongshore in the middle of a small cloud of mayflies, seen here flying over the river. They are short-lived insects that briefly emerge into adulthood—and flight—after a series of aquatic larval stages that can last a year or more. While they don’t bite, a large hatch can be big enough, and dense enough, to show up on weather radar, and can bury a beach or shoreline in dead mayflies in just a few hours.

On my way back home, I tried (and failed) to find a passage through the sandbars at the northern end of Lake Pepin.

Firmly aground a mile from shore. At one point in my ill-advised detour, I was forced to leave the boat parked securely in the middle of the lake while I wandered around the shallows looking for an escape route.

A mile wide and 1” deep. A good book and a comfortable chair can help a sailor deal with the inevitable setbacks of small-boat cruising. I’d eventually have to get up, put the book away, and find a way back to deeper water, but on a journey without a clear destination, there’s no such thing as getting lost.

Tom Pamperin is a freelance writer who lives in northwestern Wisconsin. He spends his summers cruising small boats throughout Wisconsin, the North Channel, and along the Texas coast. He is a frequent contributor to Small Boats Monthly and WoodenBoat.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Tom, My thanks, from Scotland, for a welcome break from these very odd times. Charlie

Always enjoy your adventures and writing, Tom. Hopefully, you can get back to Canadian waters next year as I, being Canadian, always think – somewhat delusional – I could do that.

Nice to read about your adventures again.Too bad about the Canadian lockout. My boat spent the summer in the water but was limited to Minnesota side of Lake of the Woods so a lot of rough open water.Nice scenery on your trip.

This has been my first time reading one of Mr. Pamperin’s articles, and I am very impressed. Jealous would be a better word, I think. Perhaps in a previous piece he has mentioned what boat this is. The photo captions indicate it is an Alaska, but an Alaska what, and built by who? It certainly looks like a sweet craft and I have a need to know….

Thanks for taking us along!

Kees,

thanks for the kind words. The Alaska was designed by Don Kurylko; you can find plans and information about his designs here.

As for building my Alaska, it was pretty much a 50/50 effort between me and my brother, I’d say.

Proof, if any was needed, that you don’t need an ocean to find adventure with a small boat. Thanks, Tom!

Thanks for the comments, everyone. Even without my usual long trip to Canada, I did manage quite a few shorter local(ish) outings in Wisconsin this past summer. This might have been the best of them!

And Tim, that’s a LOT of open water and no friendly islands on the Minnesota side of Lake of the Woods—must have made for some interesting moments!

Tom,

Thanks so much for sharing. This now landlocked ex-skipper sure enjoyed your journey. My wife and I travelled along the Minnesota side of that stretch of river on our way from Pittsburgh to White Bear Lake, MN. I could relate to your description of the terrain as you well described.

Thanks again,

Jim Fischer

PS.

That sure was Divine Intervention with saving that boy’s life!

Great story Tom, well brought to life with the right mix of prose, video, and pictures. The lifesaving event – sheer providence.

Love your work.

Yours, aye,

Sid

Jim and Sid,

Thanks for the kind words. Yep, I was really happy I had decided to sail those two miles up to Lake City that morning. As it turned out, that decision worked out very well indeed!

Tom

Your description of the Upper Mississippi River powerboats was spot on and made me laugh out loud. I had similar encounters when I passed through in a rowboat in 2018. It was great news to hear you were there to help that boy. Well done.

David,

I remember your pieces well! If I remember right, you also camped at Hok Si La on your way down Lake Pepin, right? You covered a LOT more miles than I did.

Anyone interested in reading about a longer river trip? Here it is:

David Hudson’s “Downriver—Part 1” and “Downriver—Part 2”

Tom

Hi Tom, thanks for the tale. I had a similar experience to what you describe with the drowning kid. Thanks for saving a life, I know it can stick with you in some unexpected ways. Good man.

Also, I loved the Jagular book – what became of the old boat?

Hey, Brooks, thanks for the comment. I’m glad you enjoyed my book.

JAGULAR is currently resting on some foam blocks in my shed, a little weathered but still pretty much ready to sail–I’m hoping to deliver him to a nephew this summer so he can get himself into some trouble and maybe learn something along the way. We’ll see how that goes… 🙂

Tom

Hi Tom,

Great story! As a fellow Wisconsinite, I always look forward to hearing of your adventures that aren’t traditionally coasted. I’m likely heading back to the North Channel this summer. In lieu of that (in case Canada closes again), do you have any suggestions for local adventures? I did Voyageurs last year and have done the Turtle Flambeau in the past. I’m thinking about Door County and possibly connecting that to the Garden Peninsula in da UP. That, however, might be too exposed. Do you have any other suggestions? Thanks, Fred

Fred,

As far as local(ish) adventures, I don’t think the Turtle-Flambeau can be beat for camp cruising with lots of islands. Similar, but smaller, is the Willow Flowage a bit south and east of there. If you liked the Turtle-Flambeau, the Willow is just as nice. I’ve never taken a small boat around Door County—a bit more developed/civilized than what I’m usually looking for. And so, never followed on up to the Garden Peninsula either. Another good mini-destination might be Grand Island, in Munising. You do have to wait for your weather—the west and north shore can be terribly exposed, and have long stretches of cliffs. But if you can make it around, the northern beaches are stunning. But, you really need a boat you can fully beach, because if a N wind comes up while you’re there, there will be a looooong fetch to deal with, and breaking surf.

Tom

Hi Tom,

Thoroughly enjoyed your account and those excellent pics. I have shared your video link with a few friends to give them a better idea of what row-n-sail is about. Last but not least, I was very very moved by that amazing experience you had with that drowning boy. Thanks for sharing.

Ed

A well-written story that transports me from my morning chair in Coos Bay, Oregon.

Thank you,

Don Costello

As an old magazine editor before becoming a professional mariner, I have to make one important correction to your otherwise good story. Wisconsin is NOT SURROUNDED on three sides by water. It is BORDERED on three sides. For something to be surrounded all four sides must be included. Otherwise you end up with something like, “OK, Lefty,” the sheriff hollered through the bullhorn, “we’ve got the building surrounded on three sides. There’s no way for you to escape…”

Good catch–“bordered” it is! (But somehow I’m glad Lefty has an escape route).

Tom