[M]y “gateway drug” into boatbuilding was that innocuous fitness device, the rowing machine. Whenever our CrossFit coach incorporated rowing in our workout of the day, most people groaned. I celebrated. My love of stationary rowing led me to sign up with a crew program on the Willamette River in Portland, Oregon. I’d forgotten how I loved spending time on the water, and rowing on the river is sublime. I wanted a boat of my own, but sliding-seat shells are expensive and of limited use. A friend mentioned the ease of stitch-and-glue boat building, which triggered my optimism, and in no time, without any fine-woodworking experience, I began scouring the Internet for boat plans.

Photographs by Suzanne Eggleston

Photographs by Suzanne EgglestonWeighing just over 50 lbs, the bare hull can be carried solo. The blocks that anchor the outrigger provide handholds.

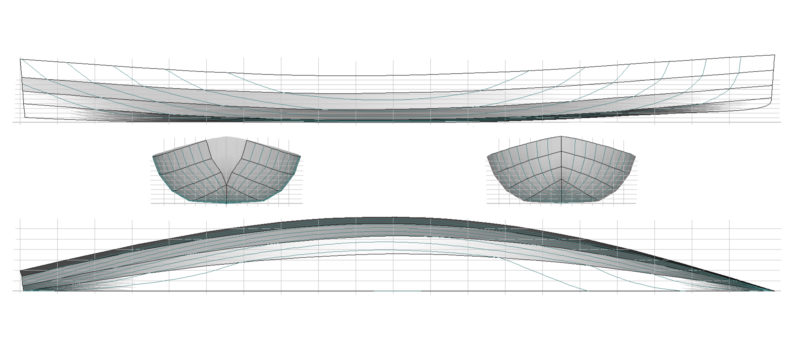

Angus Rowboats of Vancouver, British Columbia, has a nice selection of performance boats with options ranging from plans to kits to completed boats. I thought the Oxford Wherry would give me the workouts I wanted with the option to bring my wife, Suzanne, along. Angus offers the boat as a kit or as digital plans with CNC router files. I gambled that I could hire a CNC router, and ordered just the plans.

I bought the marine plywood I needed and found a guy who makes his living with a CNC router. I delivered the plywood and digital files to him, and he charged me just $90 to cut the pieces. When I glued up the finger joints, some were a little loose which, judging by the reviews, would not have been a problem if I had ordered an Angus Rowboats kit.

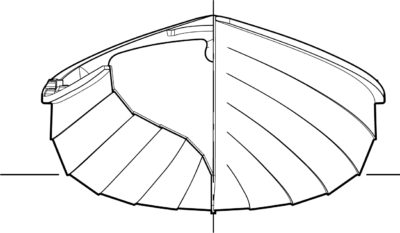

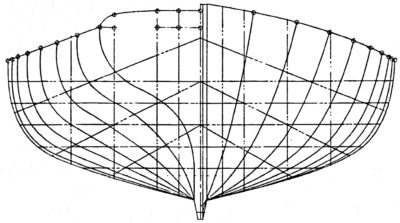

Stitching the panels together was one of the best parts of the building process, as a boat rose from the pile of plywood in just a day. Of course, as an enthusiastic rookie, I didn’t pay strict attention to the instructions and tightened the copper wires too tight. I had to loosen them and adjust the boat as I stitched the frames and transom in. More carefully following the very thorough and readable instructions of the 49-page manual, I injected epoxy into the seams, tacking the planks together and then to the three frames and two flotation-compartment bulkheads.

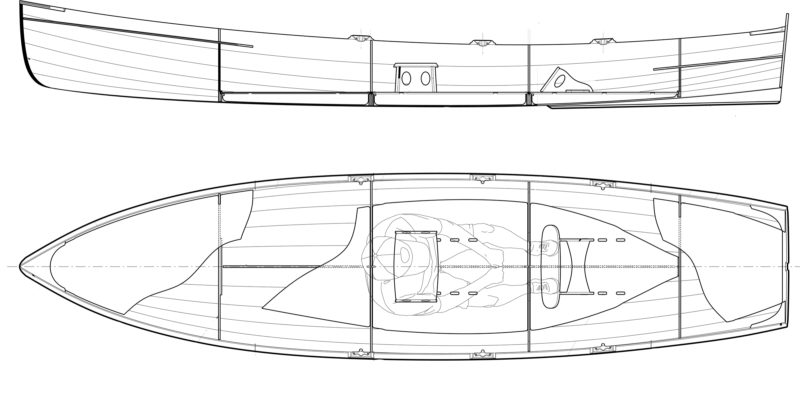

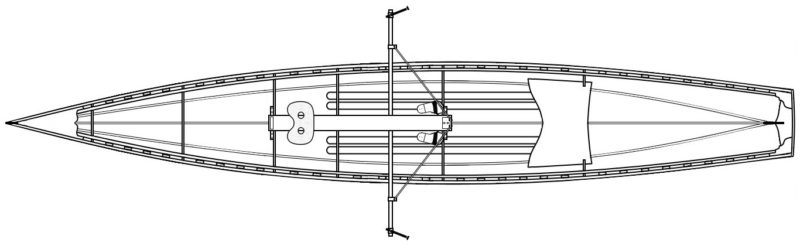

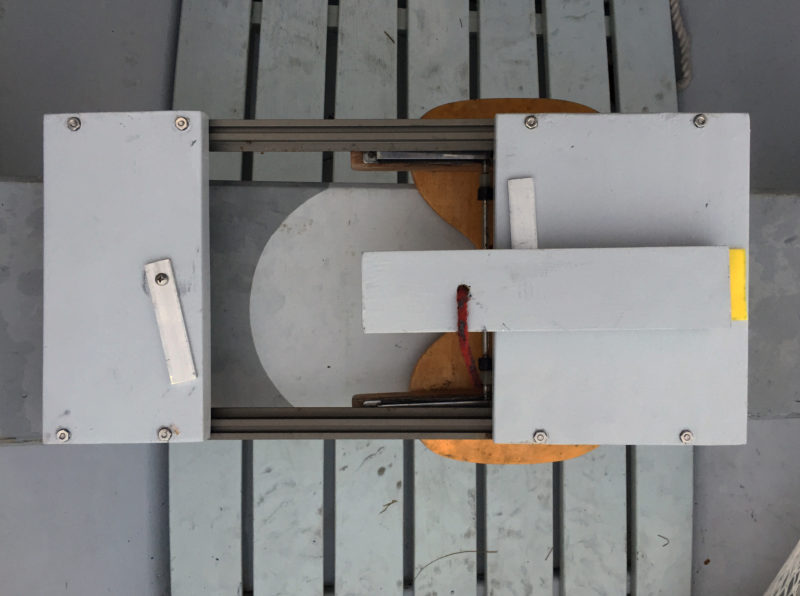

The drop-in sliding seat rig, available as a hardware kit and plans from Angus Rowboats, is an alternative to the fixed thwarts provided with the wherry kit.

After the epoxy cured, I pulled all of the copper wires, leaving tiny holes in the hull. While fiberglassing the interior, I used too much epoxy and it dripped out on the floor and the tops of my boots. The instructions don’t say to fill those holes with thickened epoxy, so I think I just used too much epoxy.

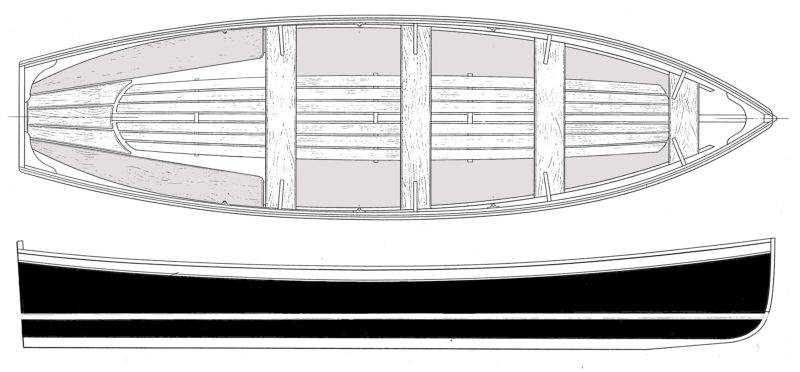

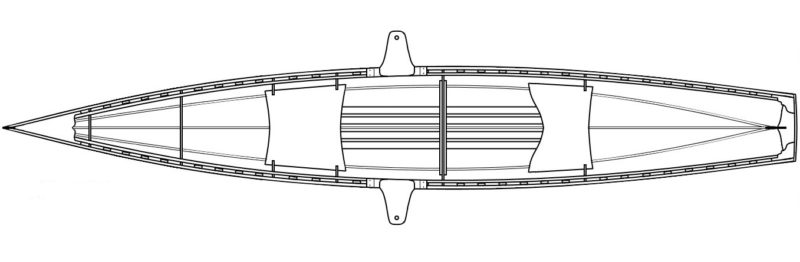

After the hull was ’glassed it was time to move on to the flotation compartment covers, quarter knees, breasthook, and gunwales. Kit builders would have the advantage with the knees and breasthook, as precut mahogany pieces are included and require only a little trimming to fit; each gunwale is made of three pieces with the scarfs already cut and ready for gluing. I don’t have a tablesaw, so I bought 1×1 red oak to piece together the breasthook, knees, and gunwales.

Despite my budding workmanship and a few errors, I finished the project and had a beautiful, shapely hull sitting in my garage. The build process was very satisfying because the design was simple yet elegant and the instructions were thorough and not overly complicated.

The instructions next called for seat installation. The kit comes with three precut cedar thwarts, but I had decided to equip the hull with a sliding seat. A commercial drop-in rig, like the Piantedosi RowWing, would fit the Oxford wherry, but I purchased the Angus sliding seat/rigger hardware kit with a carbon-fiber seat. I used clear vertical-grain Sitka spruce, as recommended by the instructions, for both the rigger and seat rails. The rigger has a span of 64” and is made of two pieces of spruce. A 1-1/2″ -wide lap joint brings the two 33-1/2″ lengths together and fiberglass is then used to reinforce it. This piece is the most beautiful length of wood I’ve ever fashioned.

An alternative to the sliding seat rig is the installation of fixed thwarts at each of the three frames and a pair of short wooden outriggers.

I had ordered Angus’s plans for hollow-loom oars, but the contractor’s tablesaw I borrowed from a friend didn’t seem capable of safely cutting the narrow strips I needed to cut, so I ordered up a pair of Concept2 carbon-fiber oars. When the oars arrived, Suzanne and I loaded the boat on the car and headed for Lacamas Lake in Washington State. The water was smooth, the late-September weather gorgeous, and with the rowing rig set in the forward position and Suzanne sitting in folding camp chair just aft of the outrigger and facing forward—a good arrangement for conversation—I managed to row the lake without crabbing an oar.

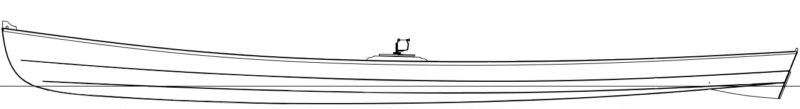

The designer sets the Oxford Wherry’s cruising speed at 3 to 4 knots and the top speed at 6-1/2 knots.

Our next outing was on Vancouver Lake, a venue for rowing competitions. We rowed across the lake and then tested our navigation abilities rowing the 16′ span between the blades down the narrow, serpentine Lake River. Once accustomed to rowing, we found the boat tracked beautifully. Course corrections are as easy as pressing harder with one foot, which translates into about a 5-degree change of direction with each stroke.

The stability added by the long sculls made it easy to get in and out of the wherry. I generally row early in the day on smooth water, and in calm conditions, the boat tracks well and glides quickly. At 235 lbs, I’m a large person, and rowing solo I have enough freeboard. Rowing with a passenger is very smooth and comfortable with minimal loss of speed and maneuverability. When I venture out alone on windy days I feel safe and rarely have water splashing aboard. With Suzanne and some gear along, the load is likely over 400 lbs and I pay more attention to chop and wakes. A bit of water may splash over the gunwale and make some bailing necessary. As with any rowing boat, it is more work to control the boat in chop, especially if taking the chop or wind on the side or the port or starboard bow. When taking waves head-on or running with a following sea, the boat handles well.

The designer compares the seaworthiness of the Oxford Wherry to that of a canoe. Equipping it with outriggers and sculls provides another measure of stability.

When I retired, I decided to do the things that I regretted not doing when I was younger. I’d been drawn to crew in college, but had been unable to participate while working full time and going to classes. It wasn’t until I was pushing 60 that I finally signed up for rowing lessons. Building the Oxford Wherry had a few of the frustrations common to a budding boatbuilder, but it was a grand adventure and rowing it has been a joyful experience.![]()

Bob Eggleston graduated from college with a degree in psychology and a passionate belief that the only meaningful job would be helping people. He found employment in secure psychiatric facilities working with pre-teens, teens, adults, and finally the elderly, but the sadness of the work took its toll. Bob moved to a more technical career with a large Oregon power company and worked his way into grid operations, partnering with brainy engineers and former Navy nuclear submariners. After a decade there, he took an early retirement to live a more interesting life and do the things he wished he had dreamed about. He moved to Port Townsend,Washington, and enrolled in the nearby Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding, to answer this question: “Can a 58-year-old former cube dweller become a productive craftsman?” Bob contently works on answering this question every day.

Oxford Wherry Particulars

[table]

Length overall/15′ 10″

Waterline length/15′ 7″

Beam/38″

Weight/53 lbs

Depth/11″

Freeboard at 250 lbs displacement/7.5″

Freeboard at 600 lbs displacement/5 ″

Cruise speed/3-4 knots

Sprint speed/6.5 knots

Maximum recommended touring load/500 lbs

Maximum recommended short-distance load/600 lbs

[/table]

Angus Rowboats offers the Oxford Wherry as digital plans with CNC router files for $129 and a complete kit for $1,399.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!