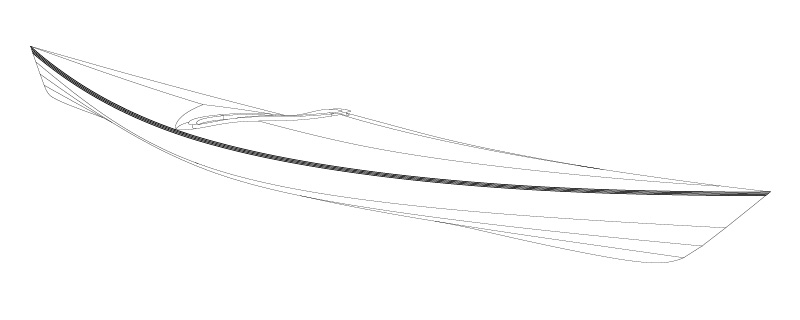

The beauty of the plastics and composites that are mainstays of modern kayak construction is that they can be molded into almost any shape imaginable, but that doesn’t assure that kayaks made from them are beautiful. Plywood is nowhere near as versatile; it can’t be shaped into a compound curve or bent around a tight radius. But just as poetry is beautiful because of and not in spite of the limitations imposed by meter and rhyme, a plywood kayak like Pygmy’s Murrelet may well owe its beauty to what plywood can’t do. The four strakes of the hull are lined off in simple but sweet curves, and the chines between them underscore the sweep of a well-defined sheerline. The small panels that provide the transition between the deck and the cockpit coaming are like gem facets. They would have been lost had the kayak been modeled for plastic or ’glass with complex curves blended one into another. The Murrelet is a boat that I won’t soon tire of looking at.

The Murrelet that I describe here is one of several versions available from Pygmy Boats in Port Townsend, Washington. You can choose a hull with a gently curved keel line for strong tracking characteristics or with a bit more rocker for greater maneuverability. There are four options for decks, each with a different balance between capacity for cargo and clearance for rolling. A choice of two cockpit-opening configurations will accommodate paddlers of different sizes. The version here is the Murrelet 2PD (two-panel deck) with the rockered hull and the longer cockpit.

The stitch-and-glue construction used for the Murrelet is straightforward and very well suited to amateur builders, even those first-timers who’ll find themselves gathering skills and tools. The building begins with joining the kit pieces that compose each full-length plank. Butt joints do the trick here and are much less fussy to work with than scarf joints. I’ve cut a lot of scarfs in the three decades I’ve been building boats, and I’m rather proud of those that I’ve done well. They can be nearly invisible under varnish, and I’m sure the countless hours of running a hand plane down stair-stepped plank sections has made me a stronger paddler. Butt joints sandwiched between fiberglass and epoxy, however, save a lot of time in the making, and they are more than strong enough. Copper wire temporarily joins the planks and deck panels together. Epoxy and fiberglass form the permanent bonds.

The Murrelet kit includes foot braces, thigh braces, hip pads, and a back brace that are all adjustable, so it is easy to get a good custom fit in the cockpit. There are two options for seating: a self-inflating foam pad and a molded closed-cell foam seat. I prefer the molded seat because it gives me a more positive connection to the kayak. For those planning to make long passages in the Murrelet, I’d recommend sculpting a custom-fit seat from a 3″-thick block of closed-cell foam. The deeper contours will relieve pressure on your “sit bones,” and making the seat’s forward edge high can support the weight of your legs. That will relieve some of the isometric tension that’s otherwise required to keep your legs locked in the thigh braces.

The Murrelet has two bulkheaded compartments for coastal-cruising gear stowage. The hatches have foam gaskets to keep the water out and three straps with anodized aluminum tensioning levers for a tight fit. The early versions of these levers used by many kayak manufacturers were prone to releasing accidentally. An errant paddle stroke or a paddler climbing back aboard after a capsize could trip the slider that secures the lever. Pygmy solved the problem by shaping the lever to keep the slider from slipping off. The Murrelet’s hatch covers will stay put and tightly sealed.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThe adjustable backrest and thigh rests, together with options for the seat, make the Murrelet easily custom-fitted to the user.

Blocking under the stowage compartment bands puts pressure on the edge gaskets to help keep water out.

A finished Murrelet should weigh about 36 lbs. That’s roughly 20 lbs less than a composite or plastic kayak of similar size, so the Murrelet is much easier to lift onto your vehicle’s roof rack. The balance point of the Murrelet happens to fall right at the thigh-brace flanges, so the common way of carrying a kayak—slinging the coaming over one shoulder—is rather uncomfortable. But there’s a better way to carry a kayak. Face the stern and flip the kayak upside down as you lift it over your head. The Murrelet’s coaming will rest on both shoulders, evenly balanced over your spine, and you’re ready for a short haul from your car to the beach and even a long portage between lakes.

Afloat, the Murrelet has very good stability. On one of my outings, I’d been surfing some modest wind waves where they steepened over a sandy shoal. I saw a freighter traveling upwind in the shipping lanes and waited for its wake to hit the shoals. When the wake and waves collided, the crests shot straight up 5′ or 6′ and exploded into spray all around me. Even buried in whitewater, the Murrelet kept its footing with very little help from me.

The secure fit I had in the cockpit allowed me to edge with confidence and get the Murrelet to carve through turns with ease. I should mention that having a rudder on a kayak does more to help you go straight than to turn. Setting the kayak on edge by lifting the knee on the inside of the turn brings the ends of the hull closer to the surface so they can more easily move sideways as they must when you turn. A rudder, even when angled for a turn, keeps the stern from swinging laterally and the kayak can’t respond well to the steering strokes you make with the paddle. It’s when you’re paddling across the wind that a rudder earns its keep. The stern, traveling through water “softened up” by the passage of the hull, will yield more than the bow to the lateral force of wind on the beam; the boat therefore veers into the wind. A rudder or a skeg can prevent this weather-cocking by keeping the stern from slipping downwind. There are, however, a few kayaks that can keep a steady course across the wind without requiring additional lateral resistance at the stern. They are exceptional (and to my mind, somewhat mysterious) combinations of hull design, windage, and trim. The Murrelet, in the conditions I paddled, was among them.

On a downwind heading, the Murrelet surfed well in following seas. As long as I got the bow properly squared up to the wave faces, the Murrelet accelerated easily to catch some good rides. On several waves, it cut through the water so cleanly when it was at speed that it suddenly went silent. I expect a lot of drama when a kayak is moving at flank speed, but the Murrelet threw no spray and uttered not a peep.

The author chose this Murrelet 2PD, which has a slightly rockered hull to improve maneuverability, together with the long-cockpit option, and found it fast, steady, responsive—and lovely to look at.

To gauge the Murrelet’s speed on still water, I ducked into a marina and fired up my GPS. It showed I could maintain 41⁄2 knots at a relaxed pace, 51⁄2 knots at a workout pace, and could do 6 knots in a short sprint. That efficiency under power should keep you from falling behind your paddling partners.

The Murrelet was designed for rolling up easily after a cap-size. If you haven’t learned to roll a kayak, you should—and not just for the margin of safety the skill offers, but also because with a boat like the Murrelet you’re missing out on the fun. The low after deck makes roll-ing a breeze. The aft end of the coaming sits a mere 71⁄2″ above the bottom, and I could lean back and lie flat on the after deck. Bringing the weight of your head and torso so close to the kayak substantially reduces the effort you have to put into rolling. Rolling using only my hands isn’t a skill I practice regularly, but I hit my first attempt at it in the Murrelet. After that, it was no surprise that many of the roll techniques I can perform in skin-on-frame Greenland kayaks I’ve built specifically for rolling translated well to the Murrelet. You could have a lot of fun in the Murrelet without ever paddling away from your launch site.

The Murrelet is a kayak that you could easily manage as a novice paddler and yet never outgrow. As your skills improve to include longer passages, rougher water, and rolling for self-rescue and for fun, the Murrelet will not come up short. And when you’re not paddling it—if you have a living room wall long enough—you’d have good reason to put it on display. It’s a work of art.![]()

—

Update: Pygmy Boats is no longer in business and kits for the Murrelet are not available. This review is presented as archival material.

The Murrelet, a plywood-epoxy kayak kit designed by John Lockwood of Pygmy Boats in Port Townsend, Washington, uses multi-chined construction, emulating round-bottomed handling characteristics and enhancing the lovely lines of the hull. Murrelet Particulars: LOA 17′, Beam 22″, Depth 12″, Weight 36 lbs

Is Pygmy still in business?

No, Pygmy closed its doors during the pandemic and there are currently no plans to re-open. I put an update at the end of the article to inform readers that the review of the Murrelet is presented as archival material.

—Ed.

I recall that Chesapeake Light Craft specified copper wire for stitching planks together, but I’m surprised that Pygmy would do that. When I built my Coho (and another one for a paying client), iron wire was provided. That’s because the stitching can (and should) be removed after glue up. Chesapeake’s scheme of pressing the copper into the chines before taping can only lead to a lumpy job, and grinding the wire flush before glassing the outside seems to obviate any supposed strength the remaining wire provides. With iron wirer, once the epoxy cures, the wire is easy to remove, and taping the inside is easy, and a good job results. The epoxy provides all the strength needed, if not more.

I, too, am sorry Lockwood gave it up. I was hoping to build one of the smaller boats for my wife (thus freeing me from the accursed tandem). Now I have to hope to find one on Craigslist.

The added rocker to the keel raises an interesting point. Sterling Donalson, of Whatcom County, is building beautiful kayaks with considerable rocker. Not only does this make them more maneuverable, but may also increase stability. That’s because the ballast (the paddler’s butt) lies below the water line. Phil Bolger designed many of his sharpies with considerable rocker, and ballast in the lowest part of the boat. The original “Egret” was designed this way, and earned a reputation for its ability to stand up to strong winds. Bolger has much to say about this.