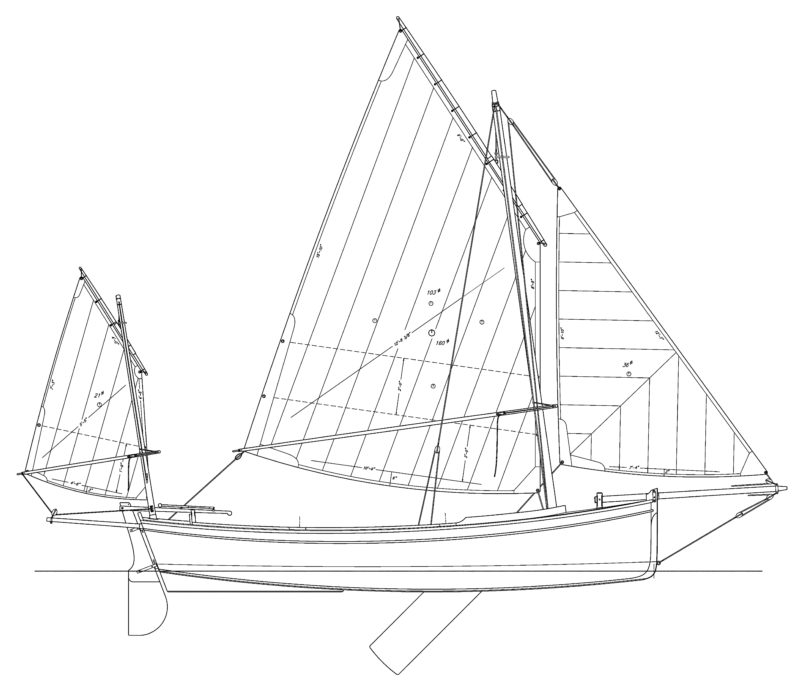

It is hard to know why a particular style of boat appeals to a sailor. A hardcore racer looks at Paper-Jet and can’t wait to strap it on, a khaki-clad prepster can’t see beyond white hulls and varnished mahogany, and a dreadlocked steampunk needs linseed-oiled interiors and a three-day grunge to feel authentic. But the nascent 19th-century romantic responds to lots of rope, multiple sails, and belaying pins, and those of us so wired are the audience for Don Kurylko’s D-18 Myst design (18′ 3″ LOA, 5′ 7″ beam). I think I can see why. The designer has worked up a robust, capable camp-cruiser or adventure expedition boat with the aesthetic appeal and features of a British working boat of a certain age.

Geoff Kerr

Geoff KerrThe D-18 Myst has a striking profile and sail plan, and her general appearance prompts thoughts of British fishing boats of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

She grabs you with her distinctive profile, offering the nicely scaled features of a much larger boat. The plumb stem and the bowsprit mimic those of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but rather than twee whimsy they are the most obvious features of a very deliberately functional boat whose dominant impression is its low yawl rig. This setup drives her character and her purpose, giving a skipper many, many options for matching sail area and configuration to the wide variety of conditions one will encounter when cruising. That the design hearkens to the 19th century is less a romantic appeal than it is recourse to the days when sail was at the height of its commercial development.

Geoff Kerr

Geoff KerrD-18 Myst is meant for adventure and exploration. Her owners, Ted and Ruth Cody, are seen here moving up a waist-deep, winding creek seeking shelter and a perfect campsite.

The D-18 Myst’s 160-sq-ft sail area is generous for a boat of this size. Ballast and her low rig keep her on her feet, and at 100′ her mainsail is man ageable singlehanded and without winches. Her relative narrowness and shallow draft (a mere 9″ with her centerboard up) make her versatile; easy trailering, storage, and rowability are desirable elements in a camp-cruiser. The tiny mizzen might appear silly until one discovers the myriad advantages of that 20′ sail when heaving to, balancing the helm, using it as a riding sail, and in helping to tack the boat in a hard chance.

An important test for the practicality of a camp-cruiser is the complexity of launch and recovery. The D-18 scores well here, with simple deck cradles for the mainmast, and all the rest of the gear simply stowed in the cockpit. Her height on the trailer makes setup possible without a ladder, with much of it, other than stepping the main, being accomplished from the ground. Only a wrench for a couple of nuts and a pair of pliers for a stubborn shackle were needed. The trailer package is clean and neat, and aerodynamic, so no cover is needed to keep gear in the boat. The rig is compact and light enough to be drawn by a sensible vehicle. The logistics on my visit were at a minimalist ramp with about 30″ of water; shallow draft and a long bowsprit for a handle make such launches a breeze. And a practical note for boat owners: a pair of 2 × 6s mounted on the trailer make great walkways. You still get your feet wet, but not much more, and you won’t stumble over axles and sea monsters.

In preparation for a daysail, the owner can do his bowsprit work in the parking lot while the boat is still on the trailer. Once rigged, the jib is set and struck, flying from the cockpit. Frankly, the rig looks (and is) busy. Sheets, halyards, running backstays, outhauls and downhauls, and cleats and belaying pins—all those components that make her a marlinespike codependent’s dream—probably make her a bit fiddly for those who are out for a mellow, social sail. The fact is, this is a real working rig, and that web of sails and control lines render Myst capable of some serious sailing. She will be upright and making progress when most boats her size have called it a day.

Auxiliary power comes in the form of oars or a small outboard. The boat’s weight and the owner’s experience call for rowing her double if an actual passage is to be made. As such the boat’s owners make regular use of a 2-hp outboard mounted on the transom. This setup moves the boat admirably, and the motor remains well out of the way perched back there. In the limited space available on this narrow transom, one must give up any thoughts of a larger engine or indeed steering with the engine rather than the rudder, so don’t plan on reverse or a sharp turn.

The designer put a lot of thought into the boat’s interior layout. There seems to be not a single square foot of space without some sort of furniture-type accommodation built into it. Thwarts double as storage lockers and the forward side benches hide bays for flotation bags or duffels, then hinge over to complete a full-beam berth flat or lounge deck. The short decks forward and aft have bulkheads forming flotation chambers large enough to compensate for the ballast. These individual features are sensible and practical for hardcore camp-cruising, albeit a bit overwhelming in the aggregate. The interior, like the rig, is busy—perhaps too busy for a sunset cruise. The owners and I sailed the boat in variable light air on a New Hampshire lake, with the furniture in the sprawling mode. I never quite found my joy, as the coaming and rail are too low to be much of a backrest, but surrendering to the supine in the sunshine was pretty sweet. Skippering aft was much more conventional and comfortable, with an ample well for feet and legs.

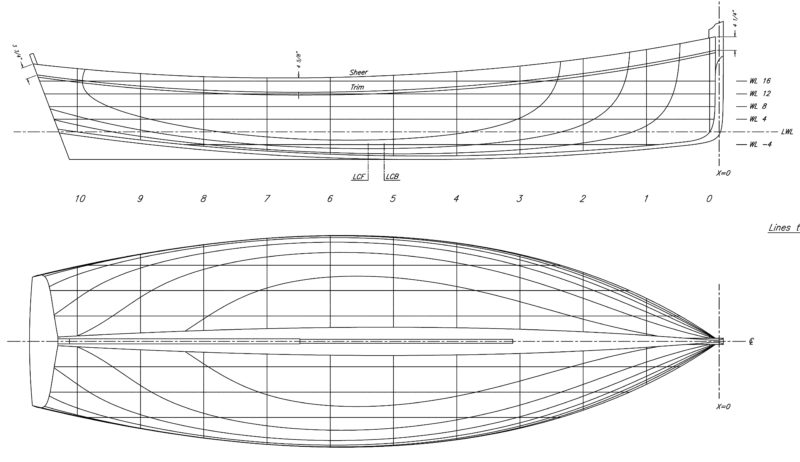

The nicely modeled hull is intended to be strip built, which is a practical construction choice for both hard use and the home builder. That home builder will find a complete and very detailed set of plans; Kurylko includes full-sized Mylar patterns for key components such as the molds. His drawings are logically organized and presented, with instructions that outline logical sequences and provide helpful hints. He gives manufacturers’ stock numbers and scaled details for the fabricator for such arcane bits as the cranse iron. Ted Cody, the builder of the boat I sampled, chose to mill his own square-section strips and edge-nail them, and then opted to sheathe the hull in fiberglass—a wise choice for an adventure-bound boat. This four-year undertaking by a minimally experienced boatbuilder is a testimony to the design, not to mention Ted’s patience and chutzpah.

Geoff Kerr

Geoff KerrA centerboard, a kick-up rudder, and an easily unshipped bowsprit make launching and recovery simple. Note the modest-sized tow vehicle and stock trailer customized with 2×6 walkways.

As built, the boat carries a heavily ballasted centerboard (75 lbs), requiring a multi-part pendant, and movable lead “muffins” in vinyl bags under the floorboards, totaling about 120 lbs. Their combined effect is a stable, comfortable boat—still subject to crew trim—but deliberate rather than flighty underway.

The D-18 Myst cannot be to everyone’s tastes. But she merits high credit and consideration for aspiring camp-cruisers and adventurers. She is dramatically more functional than a “character” boat, much more complex and capable than a daysailer, and she offers plenty of strings, jewelry, and challenge to satisfy the inner shipwright and master mariner in all of us. ![]()

Plans for the D-18 Myst are available from Duckworks. This Boat Profile was published in Small Boats 2012 and appears here as archival material.

I sure like mine! I put a couple of deep-cycle batteries next to the keel and instead of dumb weight I use them for an electric trolling motor and bilge pump. This is a great sailing boat and perfect for camp cruising!

Following Geoff’s sage advice, I’ve gradually simplified Rachel’s rig over the past 11 years. I usually sail without the sprit on the main, which works well since the sheeting angle is well aft. I’ve eliminated the running backstays and installed Dyneema fixed stays. These and a single 4:1 tackle on the bobstay are plenty adequate to keep the jib luff tensioned and allowed me to eliminate tackles at the tack and head of the jib. I’ve replaced the standing lug mizzen with a slightly larger leg-of-mutton sail. Finally, I’ve added a club to make the jib self tacking, like the main and the mizzen. All in all, I couldn’t have chosen a better camp cruiser—my pup tent fits perfectly on deck! And now, many fewer “discussions” with my beloved.

Not one single photo of the inside or any detail work?

I can’t read the D-18 Myst article even though I am a member and signed in. It keeps asking me to subscribe and does not show the rest of the article. This has happened before. How do I get this article as the 2012 annual mag does not show up under “Issues”.

Thanks.

The articles from the early print annuals are under “Series” in the menu bar at the top of the page. If you’re signed into the site you should be able to get to all of the articles there by way of their respective issues.

—Ed.

OK, I’m gonna start a discussion that never seems to get resolved.

Why is she a yawl when the mizzen is ahead of the rudder post?

The term yawl has meanings outside of the term defining a sail rig.

Falconer’s Marine Dictionary (1780):

YAWL, a wherry or small ship’s boat, usually rowed by four or six oars.

Encyclopedia of Nautical Knowledge (1953)

YAWL, …also a ship’s small working boat, or jolly-boat; in Great Britain, a boat or light vessel, usually having a sharp stern rigged with two or three lug sails; a moderate-sized rowing or sailing boat included in equipment of a British war-vessel; any small boat attached to a fishing-vessel, lightship, yacht, dredge, etc.; a dinghy.

Origin of Sea Terms (1985)

Yawl, (2) A utility boat, sometimes called a yawlboat.

—Ed.

Also, it has to do with the relative size of the mizzen (Yaw l= Smawl) (Ketch = big). So not all boats with transom mounted rudders are ketches.