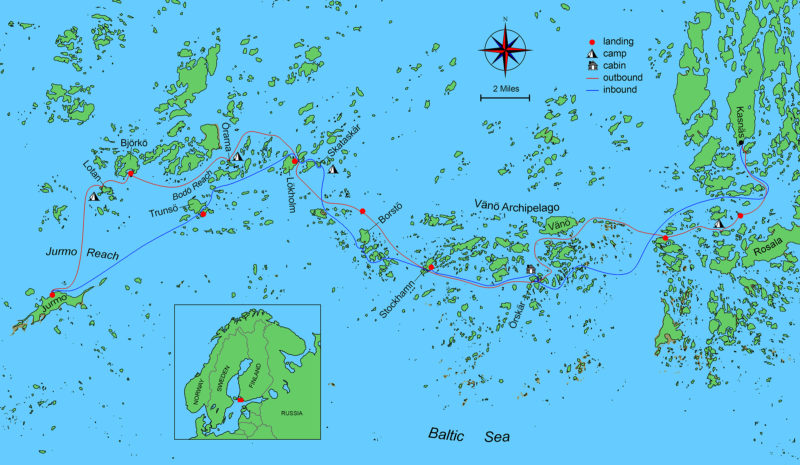

We launched our 14′ Elf faering, ELDIR, in the emerald waters of the harbor at Kasnäs. Once a remote, sleepy fishing village and ferry terminal, Kasnäs is now a bustling resort with a hotel, spa, and minigolf. A 47-mile drive from the mainland and situated at the end of a road that crosses four islands, including Finland’s largest island, Kasnäs is at the crossroads of the many passages that weave through the myriad islands of the country’s Archipelago Sea. One of the passages would give us a shortcut to the outer archipelago and the island of Jurmo where Inari, my 16-year-old daughter, was going to spend some time with her mother in a rental cabin. We decided to make a sail-and-oar adventure out of getting her there.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

The gray lapstrake hull and varnished interior of ELDIR, our little Iain Oughtred–designed plywood faering, certainly stood out from the flock of white fiberglass hulls as we loaded camping gear and prepared for sailing. We got many compliments from people passing by with their boats as ELDIR sat loaded and swaying at the end of a pier. It was late in July, and the forecast for our launch day and the week beyond promised brisk winds, so we had tied in a reef. We hoisted the lugsail, and ELDIR quickly picked up speed as we passed the harbor’s outer piers and headed to our first and somewhat protected 3-1/4-nautical-mile passage south toward Rosala. At 3-1/2 miles long, Rosala is one of the largest islands in the crowded archipelago. In the 14- to 18-knot westerly wind and on a closehauled course against a sharp 1′ to 2′ chop, we soon were pelted by spray on our faces. Avoiding an early tack, we turned east and rounded an island no more than 100 yards across that was capped with a thick stand of dark, tightly packed pine trees.

ELDIR does not have a centerboard or a daggerboard, and the unobstructed interior provides plenty of space for me and Inari. We sat on the floorboards and, with our weight low in the hull, ELDIR acted more like a ballasted ship than a 150-lb dinghy. The boat was very steady in spite of the wind and choppy water; we had no need to shift our weight to avoid excessive heeling. In previous cruises ELDIR had proven to be extremely seaworthy for her size, feeling secure even on rough passages.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorWith ELDIR on a close reach with a reefed sail, Inari kept track of our position among an often-confusing cluster of islands outside of Kasnäs Harbor. The brisk westerly wind created a sharp chop which occasionally tossed spray over our loaded boat.

For a moment, our route turned farther east onto a broad reach; ELDIR rode the waves, hissing as she exceeded hull speed and trailed twin rows of foam. We encountered a sloop closehauled temporarily turning into the wind to luff, apparently to take photos of us. We turned to windward and, as there were no more islands close by protecting us, the sharp chop grew, throwing more and more spay into and over the boat. It had been a record-breaking warm June and July and, while the air temperature had dropped into a comfortable 68 degrees, both the water and the granite islands radiated the heat they had accumulated.

Tacking through the chop north of Rosala, we made good speed in the stiff breeze but little progress on our intended southwest heading. Inari and I took turns steering and navigating. From her early years on, she has been a naturally skilled helmswoman. For navigating, we relied on paper charts and compass instead of a GPS. Only the main shipping lanes are marked, but the charts are very accurate, and often the names of the islands are descriptive—Furuskär (Pine Island), Bredskär (Broad Island)—aiding our visual navigation. ELDIR has a draft of only inches, so we could usually see any threatening underwater rocks or shallows from an unusual cresting of waves or the change in color of the sea.

Despite the warm summer the sea had been remarkably clear of algae, at least here in the Archipelago Sea. The Baltic is known to be the most polluted sea of the world: with more than 80 million people living in its drainage area and its average depth only 75′, it is continuously threatened by excessive amounts of nutrients. Several conservation measures have been taken by the countries along the coast, and there has been some improvement during recent years. On our cruise, I clearly saw some promising signs: bladderwrack, a seaweed generally perceived as a sign of a healthy sea, has regrown abundantly after many years of growing scarcer.

Tired from our morning drive and not having had coffee after lunch, I decided to aim for a 100-yard-wide treeless rocky islet coming into view over the bow. As we drew near, we saw the telltale signs of submerged rocks, dropped the sail, and struggled through the labyrinth of rocks by paddling against the wind with one oar. The islet had been inhabited by seabirds and the rank odor of guano hit us even as we secured the boat. I retrieved my mocha pot while Inari took off her wet raingear and stood on the crest of a cliff with her arms spread wide, like a seabird drying out its feathers in the warm breeze.

For our first break, we commandeered a small bare-rock islet from a flock of seabirds. The warm breeze quickly dried our spray-soaked clothes while we had coffee and chocolate.

Refreshed by coffee and chocolate, we left the islet and continued working to windward. Here the islands were closely knit, and we were more protected from the wind and waves coming from the southwest. Inari had been navigating, keeping track of our progress on the chart on her lap. After an hour, she said that we had proceeded only half a mile from our stop at the islet. She had a good point, and I decided we’d call it a day. Only 200 yards away on our port side was a small island, separated by only a 10′-wide channel from a larger island. We tacked into a cove created between the islands and landed on a rocky beach at the base of a steep, pale gray granite cliff. The depth was too much for our small anchor’s 50′ rode to get a grip, and we moved to a spot where the shore met the sea with a gentler slope. Although ELDIR was quite heavy with her load of gear, together we managed to pull her up on a gritty bedrock ledge and tie her to the trunk of an alder tree. We took a breather sitting on a rough granite outcropping that was still warm with the midday heat. To the north, the sky was washed with amber rays of the descending sun, and the distant islands were coal-black silhouettes against the pale-blue sea.

Because there is no tide in the Baltic Sea, we could anchor the boat close to shore and pitch our tent nearby in a place sheltered from the wind. At the end of the first day, we landed on a small island and tried to set an anchor from the stern and a bow rope to shore, but the water was too deep for the rode, so we pulled ELDIR up on a gently sloping shelf.

For dinner we cooked ground-chicken burgers on the Trangia stove and served them on split, toasted rolls with sliced cherry tomatoes, mixed greens, and cucumber mayonnaise. Our cliff-top feast brought a sigh of pleasure from Inari. We found a good spot for the tent, close by our boat and protected from the wind by a group of crooked pine trees.

Sometime during the night, I was awakened from a sound sleep by a peal of thunder. As rain hit the tent I rose and gathered the foulweather gear we had hung up in branches to dry and brought it into the tent.

We woke up to an overcast day and during breakfast I checked the forecast. The gale warning had been downgraded to winds of 14 to 18 knots: we could proceed with the short 2-mile unprotected crossing into the Vänö archipelago as planned. This crossing separates the inner archipelago—where the islands are larger, higher, often with steep rock shores covered with gray lichen and mostly capped with thick stands of pine trees—from the outer archipelago where diminutive islands have copses of alder scattered in small valleys in between cliffs wherever they can find some shelter from the elements and enough soil to grow from. Before the crossing we had some tacking to do into the southwesterly wind, which was bringing dark clouds that threatened rain and high wind. We sailed toward a half-mile-wide island and headed straight for a gentle slope of pale beige and gray granite. We pulled ELDIR ashore and set up our pop-up tent just as the rain started; we lay down inside and listened to the wind and rain rattle the tent.

After lunch and with the rain over, we set sail again and began the crossing in seas only 3’ high and no longer cresting. A few tacks into the crossing the wind eased, and we shook out the reef. Approaching Vänö, the largest island in an archipelago that shares its name, the rain started again, and it was soon dripping from the sails. The wind nearly died, but as we bypassed Vänö we could veer away from the wind and keep ELDIR gliding along through an intricate labyrinth of dull-gray granite islands. After a couple of hours, the rain stopped, and the sun revealed itself and turned the landscape into a palette of bright colors. Bare slopes of granite rising gently from the bright blue sea were washed in muted orange and pink.

Inari Vuorenjuuri

Inari VuorenjuuriAfter crossing over to the Vänö archipelago the wind gradually decreased and it started raining, eventually soaking us thoroughly.

Inari and I were thoroughly soaked, and despite the sun, we shivered from the cold. Luckily, our destination for the night was our summer cabin in the Vänö archipelago where I spent most of my childhood summers. After endless tacking in the feeble wind through a knot of islets, some carpeted with low wind-shorn alder trees and others just bare rock, we reached Örskär. My sister and her husband were waiting for us and had already warmed the sauna next to the cabin. They had arrived earlier, having taken the ferry to Vänö and our small open motorboat from there to Örskär. Inari and I settled into the cabin, changed out of our wet clothes, and warmed up. That evening, we relaxed in the sauna, took some refreshing dips in the sea, and had dinner before calling it a day and retiring to the cabin’s bunks for a long and peaceful sleep.

Maria Vuorenjuuri

Maria VuorenjuuriAs Inari and I left Örskär, ELDIR glided westward in a gentle breeze. My sister and her husband, aboard the family outboard skiff, accompanied us and took a few photos.

In the morning, headwinds had been forecast again, but for a moment we enjoyed sailing a gentle southerly breeze on a broad reach. As we approached a narrow channel only as wide as a paved highway east of Borstö Island, the wind turned against us. Rather than short-tack up the passage, we dropped sail and I took to the oars for the first and only time of our cruise. Once we were clear of the channel, the wind picked up, and we raised the sail again. We could bypass Borstö with a single tack and crossed the main fairway leading in an east–west direction from Vänö to Jurmo. This passage is open to winds from the east and west and, beyond Borstö, also from the south. As the wind was increasing, we chose to cross this opening and seek a more sheltered route north of the passage.

After bypassing Borstö, we stopped for lunch in the lee of an island by the open waterway leading to Jurmo. The conditions were too rough to make a direct crossing, so we headed northwest where we could take refuge among the islands.

It was lunchtime as we approached an isolated bare islet the size of a basketball court and found a spot for landing on the lee shore. As I cooked some pasta, Inari prepared a cold sauce from fresh avocado, chopped onion, garlic, lime, and chili. On the windward side of the islet, looking straight into the wind, we could see a faint silhouette of Jurmo on the horizon about 11 miles west. It seemed unreachable, as the wind and waves would keep us crawling and tacking through the maze of islands, north of the straight, open passage toward Jurmo.

While the wind made for some challenging sailing, we wouldn’t let it keep us from eating well.

During lunch the wind increased, and as we continued northwest we encountered escalating seas, although we were somewhat in the better-protected waterways. Even reefed, ELDIR was heeling more and more, and the waves hitting us astern and on the port side occasionally caused water to lap over the leeward rail. Inari, as calm and as upbeat as ever, steered with a steady hand. Her positive spirit made for pleasant company despite the occasionally challenging conditions. We changed our course farther north and aimed for the shelter of Lökholm, an island just one-half-mile across. Now on a beam reach, ELDIR rose steep wave faces to their crests, then doubled her speed on the descent to the troughs, riding one wave after another.

It wasn’t long before we entered the sheltered bay on the northeast side of Lökholm, where a half-dozen private piers and boathouses, painted red and white, were scattered all along the shore. To the south of us was a sandy beach backed by low-growing alder trees where we could land, and we took a tack back to it. As we approached, Inari lowered the sail and I poled with an oar to the beach; we would wait here for the wind to blow off its rough edge. We strolled around the island on a beautifully maintained path meandering in between the cliffs and knee-high fields of heather. The path led to an arboreal tunnel of old alders with trunks 20″ across and shadowy crowns spreading above us some 20′ high. The sun broke through the murky overcast as we passed a few old crofts and courtyards, probably now used as summer houses. Not once during the walk did we glimpse a single person, giving the island an eerie stillness.

By the time we got back to our boat, the sea had calmed and no longer was streaked with white crests, so we set out and beat to the northwest. ELDIR needed more power to get enough momentum to carry through the waves, so we shook out the reef. She pressed her lee side into the sea and started happily hobby-horsing across the swell.

We spent our third night at Örarna. With our boat’s shallow draft, we were able to stop almost anywhere, but preferred sloping rock shelves where we could pull ELDIR out of the water.

We beat along on a passage across Bodö Reach and eventually started feeling that we had had enough for one day. To the south was Örarna, a low, cruciform island made up of four ragged, intersecting peninsulas; it seemed to have a flat, level span of rock on its northern end where we could camp. We sailed ashore and bathed in the honey-colored evening light as we pulled ELDIR up on a ledge. I popped up our tent straight onto the gently sloping rock as Inari started chopping an onion for our dinner, adding chickpeas, rice, garlic, canned cherry tomatoes, and spices.

During the night, a squall passed over us, rattling the tent and pounding the fly with heavy rain. It was still raining in the morning—a good excuse to sleep in. When I got up to make breakfast there was a weak shower, and shortly afterward the sky cleared.

We carried on our battle against the wind along Bodö Reach, and the chop grew bigger as we left the shelter of Trunsö to the south of us. While Jurmo Island was to the southwest of us, our plan was to head west in the lee of a group of islands north of Jurmo Reach and then, conditions permitting, we would make the crossing. If we were lucky and the wind shifted westward, we’d have a chance to make the crossing from the north, without having to fight to windward.

We stopped for lunch just outside Björkö, behind an islet that sheltered a deep natural harbor. I rarely use the anchor, as it’s easier to pull ELDIR ashore on most stops, but decided to drop the hook here. Unfortunately, we lost the anchor—the knot holding it to the rode slipped loose from the hook as we were preparing lunch.

As our fourth day was turning into late afternoon and the brisk wind showed no signs of decreasing, we decided to seek shelter before taking on the crossing to Jurmo. I chose an island with clear views toward the stretch of open water, so we could monitor the conditions.

Before we got under way again I tied in a reef, but shortly after we departed ELDIR did not have enough power to make any real progress through the chop so we shook it out. We pounded to weather, tack after tack, and even by late afternoon the wind showed no signs of waning. I decided we’d seek shelter in a cove formed by a steep, high island called Lotan and a low small islet almost attached to it. We would have more shelter behind the steep cliffs of Lotan, but as it is easy to misjudge the conditions on the leeward side of larger islands, I preferred the low rocky shores of the islet where we would have an unobstructed view toward Jurmo and the crossing.

After we came ashore I was feeling clammy, so I took a dip while Inari sat by the cliff and read a book. We checked the weather again; the forecast was for 18 knots of wind with gusts to 25 knots. I decided that we would wait for the worst of it to blow over. From previous encounters I’d had with Jurmo Reach in bigger boats, I knew that this crossing could be more difficult than any other we had previously made with ELDIR.

Our island provided little protection from the elements, but we eventually found a spot sheltered by a bare rock knoll where our tent would not collapse under the pressure of the wind.

We popped up our tent up on the bare rock but struggled to find a spot where the wind would not collapse it. There was little shelter to be found on the islet, but we found a rock face as high as a minivan, which barely provided enough shelter for our tent. After some salad and sandwiches, we retreated to the shaking tent and set an alarm for 2 a.m. We had roughly a 24-hour weather window to get in and out of Jurmo, and there was little time to waste.

When the alarm went off I got up, but didn’t feel like I had slept at all even though I must have nodded off. I poked my head out of the tent; our map, in a plastic cover, lay just outside the tent, but I could barely see it in the darkness. I said to Inari that it would be better to wait for some morning twilight, and she agreed. We set the alarm for 4 a.m. When it went off, it woke me from a deep sleep. The wind had died down, so we promptly packed our gear and headed for the boat. Dawn and the newly risen moon cast some light on the water, and we felt confident about taking on the crossing.

During the night, the wind diminished to a gentle breeze and the sea had calmed down, so very early in the morning Inari and I took on the crossing to Jurmo. Closehauled, we could sail straight for the island and made slow but steady progress.

Close-reaching, ELDIR glided across the abated sea, as a muted red daybreak painted a glowing background to the dark silhouettes of islands around us. Inari and I sailed without saying a word.

As the sun’s bright disc gained some height above the horizon, laying its warm light on us, we drew near the end of the crossing. Jurmo’s steeply rising northern shore of rocks and sand spread out beyond the bow.

We sailed westward along a steep, boulder-strewn bank of sand. In the frail puffs of wind, we struggled to work ELDIR to weather. It would have taken us an hour or so to reach the harbor; instead, we came about and set a course toward a rocky shore close by where Inari would be staying. When we found a suitable place to get ELDIR up on the steep shore, we were relieved to have reached our destination and a little weary from the several days of arduous windward sailing. We were low on food and water, so we took a walk to the harbor where a small cafeteria and shop operates in a weathered cottage-like building—painted brick red with white trim—that sits at the root of one of the weathered wooden piers.

With the supplies we’d bought in a bag, we hiked back to our boat along a path that took us to the 56′-high summit of the Högberget, Jurmo’s highest point. The view from the top takes in the open Baltic Sea and the island’s landscape, covered in low-growing heather and juniper, that extends on narrowing snake-tail capes that meander far into the sea to the southwest and northeast.

Back at the boat, Inari and I said our farewells to each other and she returned to the harbor to rendezvous with the rest of her company for her stay on Jurmo. It was still early in the day; I tied a hammock under alder trees close by and tried to have a nap, but while I was tired, I was not sleepy. When I felt and heard the wind stirring, I decided to launch.

With an 8-knot westerly and clear skies, the return crossing with a following breeze was a relaxed one. I wanted to position myself on the north side of the eastward open-water passage from Jurmo because the next day’s forecast was for a brisk northerly breeze of 17 to 22 knots; I didn’t want to take that on closehauled. By moving northward now, I’d make the rest of the return passage on a reach or a run, depending on route selection.

Having enjoyed following winds for a change while sailing away from Jurmo, I found a convenient and beautiful campsite sheltered by crooked alder trees on the southeast shore of Skataskär, a blunt-cornered triangle of an island about 300 yards across.

I sailed 7 miles northeast from Jurmo and took a lunch break on a small islet just outside the old fishing village of Trunsö. The smoked salmon I had bought from the Jurmo shop was a welcome change to the menu. Energized by coffee, I proceeded north through the narrow passage on the east side of Trunsö and continued northeast toward Lökholm. Afternoon was turning into early evening when I began to look for a suitable island to spend the night on. I had passed several uninviting high and overgrown islands with steep and rocky shores. After sailing through the channel at Lökholm, I headed toward a cluster of small islands where I hoped to find a haven from the expected northerly. As I bypassed Skataskär’s southern cape and turned northeast, my intuition proved right: before me I saw a beautiful horseshoe bay with rocky shores and a gently sloping ledge toward which I steered ELDIR. Low and crooked alder trees provided shelter from winds, and a flat spot on the ledge where I’d landed was big enough for my tent. My refuge was painted in the soft light of the evening sun while a bank of dense, dark clouds crept in from the southwest, rumbling with thunder. I slept well in my rocky refuge.

In the morning, I woke up to a world shaded by gray clouds, with wind hissing through the alders. Although my campsite was sheltered, I could see gusts of wind changing the colors of the sea. Farther away, waves rose in white crests as they hit and tumbled over shoals and skerries. I took my time with breakfast and then prepared the boat well, anticipating a rough ride.

The first leg of my passage would be a flat run southward, so I started with a makeshift second reef by raising only the yard, leaving the boom to rest on the gunwale. This had worked well previously, when I had encountered conditions in which ELDIR would have been overpowered with only the single reef sewn in the sail. With greatly shortened sail, ELDIR was soon surging with the waves, perfectly under control. As I approached Borstö I had to decide whether to take the marked route, which required a brief tack into the wind, or to continue southeast through narrow channels between small islets. I chose the former and hoisted the yard to raise the sail with its reef tied-in and turned to weather. The wind spilling over and around land was gusting and constantly changing directions; I struggled to tack and soon gave up. I lowered the sail altogether and turned downwind. By occasionally lifting the lugsail’s yard by hand, I navigated the unfamiliar waters slowly, scouting ahead for signs of shoals or rocks.

I turned east and the route I had initially decided against turned out to be fine and sheltered by some islands. I again hoisted the sail with the single reef and was soon exposed to the north wind and waves that had gathered size and force over several miles of fetch. I was able to turn a bit more away from the wind and could feel ELDIR rising on a wave and storming along with white foam fanning out from both sides. In spite of the demanding conditions, I had a peculiar feeling of control. With the high speed the boat seemed to become more stable and needed only minor tweaks on the tiller.

After a while, as I was closing in on a narrow channel, I saw a man standing on a cliff outside a cottage and a moment later a small crowd joined him. They were all watching ELDIR, a tiny, red-sailed, ancient-looking craft riding the swell with white crests flaring from the bow. As I reached the lee of the channel, it was as if I had slammed on the brakes, leaving ELDIR only enough speed to glide gracefully along. Clearing the channel, I turned north and landed on a small bare ledge located in the middle of a sheltered cove on the east shore of Stockhamn. I shook off the adrenalin as I prepared salad and sandwiches followed by coffee. I checked my phone and saw a text from Inari: “Everything okay? I have never seen bigger waves as today on the north shore of Jurmo.”

It was still blowing quite a bit when I got underway again. I sailed in a more sheltered route toward Örskär. Broad- and beam-reaching to our cottage was a blast, although in waters somewhat sheltered by islands on the way, I was doing less surfing. The harbor by our cottage lies on the southern side of the island, and it took quite a bit of tacking to enter it, the wind being gusty and shifting as it passed over the island. I spent a pleasant afternoon and evening enjoying the sauna, dinner, and the company of my sister and her husband.

From Örskär I had only 11 miles left to reach Kasnäs. The weather was docile with bright blue skies and a following wind of 6 to 10 knots. Instead of the regular, more protected routes, I chose to sail northeast from our harbor into a scattering of islands and islets. To navigate through granite skerries and islets, I kept my finger on the map and counted the islands as I passed by.

After half an hour or so I had avoided all the hidden shallows and rocks and was through the Vänö archipelago, sailing open water toward the Rosala archipelago. ELDIR rocked gently in the swell, and my last passage was again more sheltered. I eventually turned north toward Kasnäs Harbor and sailed all the way right up to the boat ramp. Exhausted by six days of challenging sailing, I stepped out of ELDIR feeling very much alive. ![]()

Mats Vuorenjuuri is the father of three and has been an entrepreneur making a living in graphic design, photography, freelance writing, and most recently as a boatbuilder as well, offering boatbuilding and maintenance services through Nordic Craft. After sailing various types of vessels,including sail-training schooners, he enjoys the simplicity and pleasures of small boats . He wrote about cruising the Finnish coast in his Coquina in our May 2016 issue and about a Lakeland Row in January 2017.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Great story Mats!

Once again proof that the size of the adventure is not limited by the size of the boat.

Oh Mats, this is a wonderful trip you have given us. I have a 17′ fjaering as well. Your video was so sweet!! Thank you and Inari for this fine example of seamanship.

Thanks for writing about your trip–I really enjoyed it. It’s good to see youngsters willing to be involved in small-boat cruising. And wow! What a great cruising area. It reminds me so much of Lake Huron’s Georgian Bay, with no tides, exposed granite, and pines. If you ever made it to the Great Lakes you’d feel right at home.

-Tom

Hi Mats,

Thanks for sharing your adventure on this beautiful handmade boat.

Best regards,

Ralf

Thanks, Mats, for the enjoyable story, photos, and video. I have three questions: ELDIR doesn’t appear to have any buoyancy tanks or bags – if you capsized would you be able to bail her out and get underway again without assistance? Secondly, how do you avoid scratching or gouging the hull when hauling it up onto rock ledges – using rollers? Lastly, what holds the tent down when you set up camp on rock?

Thank you Andy,

We have a couple of inflatable rollers that are tied under the forward bench while sailing, and when pulling ELDIR up on rock ledges, one of them is tossed under the boat. The keel has a brass keel guard. We get some scratches every now and then, but I have stopped worrying about them, and fix if needed. In addition to these rollers, our clothes are in watertight bags, which we jam under the center or aft thwart. I have not done a capsize recovery test with ELDIR (should do) but take every precaution I can, in avoiding capsize or flooding. Most of all, we follow the weather closely and plan accordingly, avoiding getting into circumstances that would be too much.

If we use the tent on rock we use rocks as weights under each corner of the tent.

Thanks for your reply, Mats.

Thank you for your comments and for taking the time to read the story. As the snow and ice are slowly giving away, it is time to plan or at least dream of another adventure.

Hi Mats,

I loved to read your story since I am sailing also longer trips in open boats in the Swedish skerries. Of particular interest is the lug sail. Did you try without boom? I have an even smaller boat and sail the lug rig loose-footed without boom. I arranged a the mast in a slight backward angle to have space for rowing and sitting. Do you have a sailplan?

Hi Mats,

I’m a little late in reading your article but enjoyed it very much. I’m getting ready to build an Elf myself and am curios about your boat not having a centerboard as the plans show. Did you place any internal ballast? If not I commend your sailing abilities. Again, wonderful article. Thanks,

Randy

A great adventure indeed. Wow, what an amazing experience. I’m building my SW Dory in Langkawi, Malaysia, and this is inspiring stuff.

Many thanks,

Ed