On a warm midday in November, I cast ARR & ARR’s lines off from the dock at Goose Island State Park and rowed into the fickle breeze coming down the double row of low pilings marking the channel to Aransas Bay on the south-central Texas coast. The channel was only 100′ wide, too narrow to beat to weather in the light air with a balanced lug—at least for me—especially with fishermen or hunters speeding back to the park’s ramp in their high-powered skiffs and airboats. Instead, I rowed across the shallows between the channel and the park’s 800′ fishing pier.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorAfter a 3-hour drive from my home in Austin, I left my car and trailer at a campsite at Goose Island State Park while I explored the bays. The landscape of the Texas Coastal Bend is flat with sand and shell beaches, brackish marshes, and bay depths of only 10′ to 15′. While mild conditions are the norm in early November, northers can blow through and drop temperatures 20 or 30 degrees in only minutes and build up a steep chop. I was fortunate to have five straight days ahead with afternoon highs near 80, overnight lows in the 60s, mostly clear skies, and winds rarely over 15 knots.

Near the steps that lead down from the pier into the water, two anglers in waders cast lines in long arcs. A kayak fisherman floating just past the end of the pier reeled in a slack line little by little. He paid no attention to me as I rowed past him on the side of his kayak opposite his fishing line, but a man and a boy standing on the end of the pier waved to me. I returned a wave and rowed another 1/4 mile into Aransas Bay. The bay was crinkled by wavelets in the light air. I had only 5 miles to go that afternoon, so I took my time stowing the oars, fenders, and dock lines before raising the sail.

I would rendezvous with another seven or eight boats across the bay at Paul’s Mott, a point of scrub and shell jutting about 1/4 mile into the bay from San José Island, for our first of two nights camping together. Most of them had set sail from Rockport an hour or two earlier. I would have launched from there as well, but I planned to spend an extra two days and nights exploring Aransas Bay by myself after they all headed home, so I left my car and trailer in the Goose Island campground where the gates are locked at night, giving me peace of mind and allowing me to relax completely.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

Oyster reefs run out into the bay in a broken line from Paul’s Mott. In the light air, waves wouldn’t break over the reefs, and with the murky water, I doubted I’d be able to see them. The Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) crosses the bay left and right about two thirds of the way to Paul’s Mott. Crossing the navigational channel at its marker 15 would keep ARR & ARR well away from the reefs, so I sailed closehauled south-southeast, as close to the marker’s bearing as I could while still maintaining 2 or 3 knots.

Within half an hour, the wind freshened to the 5 to 10 knots that had been forecast. It was easy sailing under a clear sunny sky, exactly the stuff I had wanted after months of being cooped up with a computer in what had become my office at home.

Tugboats pushing barges paired end-to-end crossed in the distance from left and right. I studied their courses through my monocular and made out the ICW’s numbered markers, green square and red triangular signs set on piles driven either side of the route. Two tacks put me back on track toward marker 15 and put more distance between ARR & ARR and the reefs, and I crossed the ICW during a lull in the barge traffic. By then, the wind had picked up another few knots, so I was able to point higher and made Paul’s Mott after only another hour on a single tack of easy sailing.

While I was still 200 yards from the point, where the chart shows a dip in the reef to a depth of 2′ to 3′, I raised the daggerboard and crossed the reef on a reach. Once on the other side of the reef and back in 5′ to 10′ of water, I put the board back down and closehauled back toward shore, where two boats were beached near a large portable canopy with a peaked fabric top.

Oddly, neither boat had a mast. I tried to recall if any of the group I planned to meet were to arrive in powerboats. I’d figure out what was what after I beached ARR & ARR. To cross the last 100 or so shallow yards to the beach, I dropped sail, unfastened the sheet’s lower block from its anchor point on the main thwart and moved it to a quarter cleat, swapped the daggerboard for the slot’s rowing plug, and set to rowing.

I heard “ARR & ARR, ARR & ARR, this is MYSTERY MACHINE, over” from the handheld VHF clipped on the front of my PFD. Matt, the sailor who had organized the trip, informed me that our group was not at Paul’s Mott—that the spot had been occupied when they had arrived—but about a mile southwest instead. I noticed a cluster of five masts then, well down the coast.

I decided to row instead of raising sail again and bent to the oars. I hadn’t rowed regularly in months, and it felt good to work my back and arms again. ARR & ARR slipped past the coast of waist-high cordgrass dotted with tiny oyster shell beaches, chest-high mangrove clumps, and narrow gaps where sloughs led into the island’s interior.

At our first night’s camp on San José Island, Matt, Ziggy, Dave, and I pitched our tents on the higher ground near the vegetation line. The island beaches in Aransas Bay are mostly oyster shell, and the water from the bay, at left, seeps through the sieve of piled-up shell to and from saltwater pools, at right, making them rise and fall with the tides.

MYSTERY MACHINE, Matt’s modified Bolger Featherwind, and MARILYN J, Glenn’s Mayfly 16, were already pulled up on the shell beach; Bobby and his wife Pam, with PILGRIM, a custom Princess 22 cat ketch, floated about 20′ off the beach on a bow anchor and a stern line run ashore; and CHICKEN PARTS, a MacGregor 26, swung on anchor about 100 yards out. I rowed ashore between MARILYN J and PILGRIM, stepped out, and pulled ARR & ARR’s bow as high as I could onto the beach.

The beach was mainly broken oyster shell piled into ridges paralleling the water and varied from as narrow as 10′ where I had beached ARR & ARR to as wide as 40′ interrupted with a saltwater pool so wide that cat’s-paws scurried across its surface.

Behind the beach, where soil mixed with the shell, thick vegetation transitioned through narrow, distinct bands. Closest to the shell beach and spreading onto parts of it were ankle-high saltwort, salt-tolerant succulents with pink runners and thick, light-green, inch-long leaves. Behind that was a dense, soft, shin-high layer of saltgrass, its narrow dark-green leaves in herringbone patterns that reminded me of the softer evergreens. Interspersed with the saltgrass were patches of prickly pear and knee-high sea oxeye daisy, some with dark, dried flower discs long gone to seed. The ground behind dipped back down into swampy swales and sloughs lined with cordgrass. Twisted limbs of scrub oak reached skyward above bushy, dark green mangroves.

As I unloaded ARR & ARR to make my camp, two WindRider 17 trimarans arrived, one skippered by Ziggy and the other by Dave, whom I had met the year before on a similar excursion. The three of us set up our tents at the edge of camp, on the flatter, higher ridge of shell running along the back edge of the beach’s wider stretch, next to the vegetation and separated from the shoreline by that pond-sized saltwater pool.

The tide would rise only 6″ or so overnight, and the wind was forecast to lighten and continue blowing across the island and out into the bay, so Ziggy, Dave, Matt, and I—those of us with tents—left our boats pulled up on the beach with anchors set on shore. Glenn planned to sleep aboard MARILYN J, so he repositioned her just off the beach with a stern anchor and a bow line running to shore.

Dave and I caught up over our dinners, he on his chair next to his tent and me, maintaining safe social distancing, on my two-gallon bucket next to mine.

Michael sailed in on RED TOP, a highly modified Lehman 12, and anchored about 15′ off of San José Island. The barge in the background stayed in place overnight and was on its way early the next morning before we got underway.

While we ate and chatted, a tiny red and green boat sailed in from the direction of Rockport and dropped anchor just 15’ from shore. It was RED TOP, a highly modified Lehman 12, now with a lugsail, leeboards, and a cuddy cabin. After stowing the sail, Michael, its skipper, came ashore and joined in the still-scattered reunions and conversation.

Most of us had brought firewood along—driftwood being rare on these bay beaches—and soon after dark, Matt had a fire going. An inflatable tender motored in from CHICKEN PARTS and Nick and his young son Mason disembarked. We gathered in ones and twos around the fire until the whole group of nine or ten was present. The air was pleasantly warm, so we didn’t sit in a circle around the fire but sat in a rough line stretched along the narrow beach facing the bay instead. I sat on my bucket at one end of the line, vigilant about keeping the recommended 6′ from anyone else whenever in company for more than a few seconds, but with the wind blowing across our line and out into the bay instead of along the line, even that was probably unnecessary.

I mostly listened, taking in the others’ stories and plans as much as I did the breeze and the deepening black sky. Mars shone bright and orange high in the southern sky, and Jupiter and Saturn stood poised above the horizon where the sun had set.

After daylight the next morning, we took our time breaking camp. I made a cup of coffee and sat on my bucket outside my tent. An airboat hummed in the distance and a bird trilled from somewhere in the cordgrass or mangroves, then went silent at the dull thud, thud of hunters’ distant gunfire. Ducks flew in wavy lines over the island.

The air was only slightly cool. I hadn’t even pulled my sleeping bag from its dry bag the night before, but had instead slept directly on my sleeping mat, comfortable just wearing jeans and a fleece shirt.

I walked down to the boats with the last of my coffee. The wind blew across the island from the east, so the waves were small but fell obliquely against the shore and had pushed ARR & ARR beam-to the shell beach. With her V-shaped hull, she rolled with the waves and ground against the shells. I knew it had probably done a number on the paint job during the night but hoped the double layer of fiberglass I had laid over her keel when I built her had provided adequate protection. I couldn’t see any damage, and I wouldn’t know for sure until I had her out of the water at the trip’s end, but this was exactly the type of camp-cruising wear and tear I had built her for.

I changed from my camp clothes back into the previous day’s quick-drying hiking wear and neoprene booties, broke camp, loaded the boat, and started to rig her for sailing. I had left the rowing plug in the daggerboard slot overnight, and now it was jammed in place by bits of shell that had worked their way into the slot.

I pushed the boat a few feet into the water, rocked her to work the water in the slot, and tried to wiggle the plug loose, but it didn’t budge. Using my push pole’s unattached duck foot, I pried the top of the plug away from the top of the slot, and the plug finally came out, the bits of shell grinding and squealing between the plug and the inside of the slot. I scooped water into the slot with my bailer to rinse away any remaining shell.

We planned to camp that night on 3-1/2-mile-long Mud Island, only 7 or 8 miles southwest, at most a couple hours’ sail, so most of our group were sailing back to Rockport to have lunch at a dockside bar and grill. I had been avoiding public places, and even though Aransas County had reported only one or two confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the previous week, I joined the others to head straight to Mud Island to see if the 2020 hurricane season, particularly Hurricane Hanna, had left either of two naturally fluctuating passes through the island suitable for our boats and tents. I also wanted to explore Blind Pass, the 60-yard-wide gap between Mud and 19-mile-long San José Island, for possible future overnight trips. Satellite images I’d studied showed what looked like promising beaches flanking the pass.

I shoved off and joined MYSTERY MACHINE, MARILYN J, and RED TOP on a broad reach under full sail south along the protected west coast of San José Island. Except for a few puffy white clouds just above the horizon, the sky was an unbroken expanse of blue. The wind grew from gentle to moderate, and soon we were sailing at 4 or 5 knots through only wavelets in the lee of the island. Dolphins converged on our boats and swam along for 15 or 20 minutes, moving mostly as a group from one boat to the next.

Dolphins are common in Texas bays, and the pod that accompanied ARR & ARR in Corpus Christi Bay seemed especially engaging, sometimes swimming so close that their puffy exhalations misted my face. On the low line of land on the horizon sit Point of Mustang and, tiny at the right, Port Aransas, marked by the towers of three deepwater drill rigs.

When we reached Mud Island, we sailed west along its northern side looking for the two cuts and beached our boats in what we thought was the smaller, easternmost one. A 15-yard-wide channel flowed north to south through the island between oyster shell beaches. The western beach was too short and steep to pitch tents on, but the eastern beach was a good 100′ by 50′ and curled around in a short hook at its southern tip, creating a sheltered cove that had deep water right up to shore along most of its length. The surface of the water flowing through the cut churned in eddies and swirls in a 4- to 5-knot current. Dolphins surfaced in tight arcs in the cut, likely after fish.

Like the beach we had camped on at San José Island, this beach consisted primarily of oyster shells piled in ridges, with a few wide depressions in the beach’s middle, some with shallow pools.

We relaunched and continued west looking for the larger cut. After a mile or so of sailing by nothing but narrow, steep shell beaches backed by unbroken mangrove thickets, we realized that we had landed in what had been the larger cut and that the smaller cut must have closed up, so we returned to where we had originally landed, beached our boats in the hooked cove, and scouted out tent sites.

The predominant plant on that part of Mud Island is black mangrove, growing too thickly to easily walk through and ranging from knee- to chest-high, with stiff, dark-green oval leaves only an inch or two long and seeds the color and shape of large lima beans. Sea ox-eye was thick there too, along the edge of the mangroves, and salt-tolerant succulents grew here and there. Sea purslane sprawled across low stretches of bare shell in the depressions, the purslane’s pink runners and 1″ leaves looking like saltwort at first, but with flat leaves instead of the bulbous succulent ones and with five-pointed, purplish pink flowers the size of a pinky fingernail.

Having found several good patches of flat ground, we returned to the boats. We had the entire afternoon remaining, so Matt and I decided to circumnavigate the eastern part of the island. We walked our boats from the sheltered cove, around the hook, and against the current along our side of the cut and launched from the cut’s entrance. We both set sail, and Matt pulled well away from me in only five or ten minutes. MYSTERY MACHINE bettered ARR & ARR in both pointing and footing.

Not wanting to admit that Matt was simply the better sailor, I decided that ARR & ARR was undercanvased, so I set a new jib I had been eager to experiment with. To accommodate the addition of the jib, I moved the main aft by setting the balanced lug as a standing lug. I moved the boom vang to the tack to serve as a downhaul, and let the downhaul move aft to become the vang. I set the little jib flying, and with the new sail plan’s center of effort properly set, ARR & ARR, now a sloop, took off.

I had not yet installed cam cleats for the jib sheets, so I had to hold both sheets, jib and main, in one hand while managing the tiller with the other. The boom still stuck a bit forward of the mast, and on each tack, the jib sheet caught on it. But the boat did make good speed and pointed higher.

I found Matt waiting for me at Blind Pass, and we sailed together through it. MYSTERY MACHINE drew less than ARR & ARR and my daggerboard hit the bottom several times. Although I quickly released both sheets, spilling most of the air from the sails, ARR & ARR pivoted on the grounded board and turned her beam to the wind. I pulled the daggerboard up and sheeted the jib to turn the bow downwind to get moving again.

We sailed on a broad reach up the southern side of Mud Island. This side of the island didn’t have beaches but was more of a wetland, with mangrove islets of all sizes scattered among inlets and flats. Although the water was opaque with mud and the chart showed less than a foot there, I didn’t run aground again.

At our second camp, on Mud Island, the little cove on the south side of the cut was deep enough right up to the beach that even PILGRIM and CHICKEN PARTS were able to nuzzle up to shore still fully afloat.

We beached back in the cut’s little cove, and before long we were joined by the four boats that had gone to Rockport for lunch. The cove was deep enough for even PILGRIM and CHICKEN PARTS to nuzzle up to the shell beach while fully afloat, and set anchors ashore on dry land.

RED TOP left by early evening, and two other boats joined us, CHEESE CUTTER II, a Hobie trimaran with skipper Chris aboard, and a Westsail 32. The Westsail came in under full sail and anchored a good 1/4 mile off Mud Island’s northern shore, and its crew—Chris, Cathy, and dog, Gus—sailed into camp on its lug-rigged tender with a tanbark sail.

At dusk, we collected the rest of the firewood we’d brought and gathered around in the warmth and light of the fire as Jupiter and Saturn set and Orion rose high in the darkened sky. I mentioned wanting to spend the next day sailing 15 to 20 miles north to explore Cedar Bayou, the 3-mile-long natural cut that separates San José and Matagorda islands and sometimes connects Mesquite Bay with the gulf. Matt suggested that, given the north wind forecast for the next day and the south wind for the day after that, I should go with the wind instead of against it to some beaches he had seen on Mustang Island’s Corpus Christi Bay side on a previous trip. Sailing with the wind abaft the beam both days was appealing, so that became my plan.

Glenn, Dave, and Matt (left to right) enjoyed fishing, coffee, and chatting on the second morning, at the cut through Mud Island, while maintaining safe social distancing.

The next morning was calm. On the south side of camp, the still water in the cove reflected the boats’ hulls and masts and the wetlands’ little islands of cordgrass in a perfect mirror of the sky’s growing gray-orange light. A haze on the eastern horizon separated the mile-long stretch of Mud Island’s mangroves from a line of palm trees on San José Island beyond. To the north, toward Rockport, the water rippled in the distance but had only dull crinkles next to shore. Dull thuds of duck hunters’ gunshots and the distant thrumming of engines carried through the still air but, with the air so heavy with moisture, I couldn’t tell which direction the sounds came from.

The saltwater pools in our beach’s wide depressions had risen overnight. The water in one had even reached the foot of Matt’s tent. It surprised me, because the night had been calm and dry, except for the heavy dew. Matt and Glenn surmised that the rising tide must have seeped through the coarse shell ground as through a sieve, which would explain why the depressions at our camps had water in them, despite no visible inlets and no recent rain.

In the early orange light, Rockport’s lone spheroid water tower and row of two-story buildings were strung along the northern horizon, like a string of pastel-colored beads. A haze over the rippled bay thickened until the entire horizon dulled and then disappeared.

The haze moved toward us in a thick bank. Fog. On the Coastal Bend. It is rare and was a first for me.

To the southwest, where I had decided to go, the water and horizon were clear. Even three deepwater drill rigs in Port Aransas were visible though low, tiny, and washed-out from the 6 or 7 miles’ distance. A moderate southwesterly breeze was forecast, and an encouraging hint of that breeze touched the back of my neck.

I was eager to get going, before the fog could reach Mud Island, so I said my goodbyes to the other sailors and raised ARR & ARR’s sail, leaving the jib stowed this time. I set the downhaul snug but not tight, so the sail could stay out perpendicular in the light air and catch what little there was. Chris, CHEESE CUTTER II’s skipper, gave ARR & ARR a good push to set me on my way, and I drifted from Mud Island at a turtle’s pace. The water had gentle dull ripples, like wavy window glass in a century-old home.

Sailing at a lazy pace, ARR & ARR didn’t need my full attention, so I gazed over the stern and watched the others leave the campsite for Rockport. One by one, they set sail and vanished into the fog. Whenever one hailed another on the VHF, I switched with them from 16 to the working channel and eavesdropped. I wanted to learn what sort of coordinating they were doing in the fog, and it made my departure feel less abrupt. Eventually, even their radio calls were out of reach.

ARR & ARR drifted past one of the lima-bean-looking black mangrove seeds floating on the bay, then another. I counted the seconds it took one seed to travel the 15′ from bow to stern—five or six seconds, which meant I was moving at only about 1-1/2 knots. I settled in on the sternsheets on the starboard side of the tiller, resting back against a dry bag, and enjoyed the easygoing morning.

A couple of hours passed before the breeze picked up, but by noon I was sailing up the channel to Port Aransas on a reach past the Lydia Ann Lighthouse, a 68′-tall tapered octagonal tower of red brick with four low, weathered wooden buildings tucked about 200 yards back into the surrounding mangrove marsh. Just past the lighthouse, on its south side, a bayou led from the channel into the marsh and next to the lighthouse.

In the nearly two centuries since the lighthouse was built, Aransas Pass—the channel separating Mustang and San José islands and connecting Corpus Christi Bay with the gulf—has shifted a mile south, so it wasn’t until the lighthouse was well astern that I rounded the point and sailed down Corpus Christi Channel.

ARR & ARR, sailing on a run down Corpus Christi Channel on the third day, passed three deepwater drill rigs under construction or repair in Port Aransas. The oarlock sockets on ARR & ARR’s transom allow me to use an oar as an emergency rudder if the need arises.

I was especially glad to have the wind driving ARR & ARR along the channel, while I watched for ship and barge traffic. About 1/2 mile down the channel, the ferries shuttling between Harbor and Mustang islands timed their 1/4-mile crossings to avoid me, and I was glad I didn’t have to hold them up too long.

On my approach to Sting Ray Hole, a 1/2-mile-wide pass between the sand-spit ends of Pelican Island and Point of Mustang, two white pelicans flew overhead, their black wingtips stark against their bright white plumage. Once through the pass and into the easternmost part of Corpus Christi Bay, I skirted the East Flats, a 2-mile stretch of shallows and low, mangrove-covered islets, and sailed closehauled toward the shoreline just south of the flats. The closer I got to the low stretch of undeveloped greenery, the more patches of white I saw between it and the water. I pulled the daggerboard up 8″ or 10″ to reduce draft without sacrificing too much pointing ability and aimed for the windward side of one of the larger white patches.

I pulled ARR & ARR ashore to camp on Mustang Island. The beaches in Corpus Christi Bay are white sand with clamshells instead of the piles of oyster shells that make up Aransas Bay’s beaches. Visible at left on the horizon are the storage tanks of an oil-export terminal at Ingleside.

I approached three beaches, the first two about the size of a modest kitchen, and settled on the third one, which was larger and higher than the others. Instead of mounds of oyster shells, these beaches were white sand just peppered with clamshells.

Beyond the mangrove wetlands, Port Aransas was still visible on the horizon from the three deepwater drill rigs—small and hazy in the northeast—to the low dark, angular spread of downtown buildings and the sprawl of two- and three-story homes to the east. Across Corpus Christi Bay, an oil export terminal’s spread of wide, squat, cylindrical storage tanks glowed with a bright splash of white sunlight.

All around me, silent except for the shush of wavelets on the sand and the occasional quack of a duck, was the wide, nearly motionless lapis and teal bay. Vast spreads of navel-high mangroves were interwoven with brackish bayous and sloughs. A quarter mile toward the thick spread of homes to the east, a man in waders fished 20 yards from a boat half hidden by mangroves. A skein of ducks flew overhead, all black except for flashes of white with the upward movement of their wings. This part of Mustang Island was an island of its own, an oasis of wild in the midst of human development.

I ate dinner cold: chowder straight from its can, the last bits sopped up with flatbread. It was simple and surprisingly good.

Although my mostly screen tent would have been comfortable with the light air and the pleasant temperature, the heavy dew that sets in overnight warrants setting the fly. After pitching the tent, I could change into dry camp clothes and hang up the day’s damp clothes to dry on paracord run between the tent’s inside webbing anchor points.

It was nice to be camping by myself. While I was sitting on the bucket watching the sun set, my shoulders and back relaxed and I felt as if my body’s weight had settled into my hips from its perch on tense shoulders. I had thoroughly enjoyed my time with the other sailors and was eager to see them again on future trips, but I prefer to do the social thing only in bits.

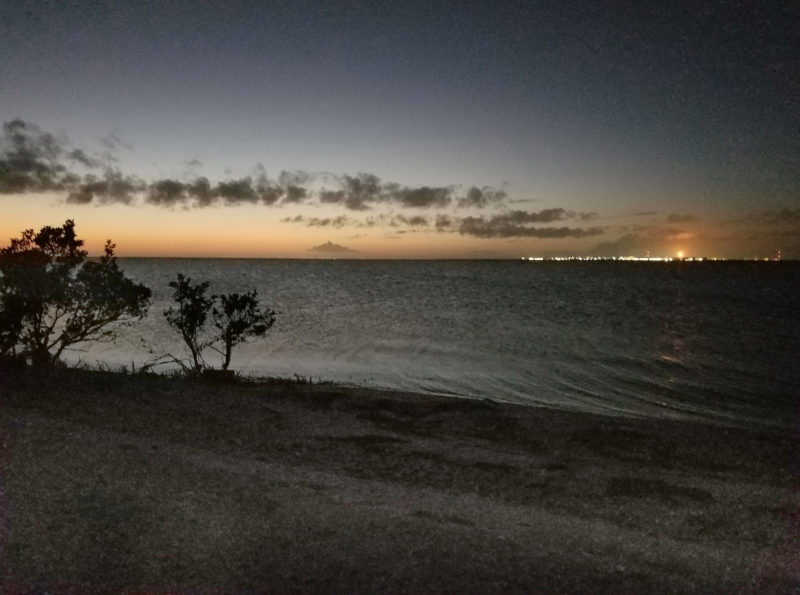

As darkness fell on Corpus Christi Bay, the oil export terminal at Ingleside lit up the horizon. The bright orange light, the fire on top of the flare stack, was clearly visible from the previous night’s camp at Mud Island, 14 miles away, and even discernible from Paul’s Mott, at 22 miles.

The last of the sunlight faded. The lights of Corpus Cristi and Port Aransas filled the horizon and spilled their glow into the night sky, masking all but the brightest stars.

I heard a puffy exhalation coming from out in the bay. I didn’t see a disturbance on the water’s surface. If it had been a dolphin, it could have covered a lot of distance before surfacing again. I didn’t hear it again.

I put my bread-mopped chowder can in with the rest of my double-bagged garbage, sealed the bags inside the bucket, and set the bucket on a clear spot of sand and shell 30’ from my tent. I crawled into the tent and fell asleep within minutes.

I woke up cold in the middle of the night. The half moon had risen and my tent was glowing in its light. I crawled out of the tent, pulled my sweatshirt out of its dry bag, and put it on over the fleece shirt I had been sleeping in. The bay was like glass, without the slightest of undulations. The light breeze, coming from over the land, didn’t stir the water’s surface for as far as I could see. The tide had come in, and ARR & ARR floated, motionless, 1’ from the beach with her stern pointed straight out into the bay. Having warmed up, I stayed up for a while and took in the stillness.

I turned in and when I woke again in the early morning light, the gentle breeze was still blowing across the land and into the bay. Low, thin puffs of gray clouds drifted north. ARR & ARR still floated free of the beach, but tugged gently at her anchor line.

I ate a breakfast of granola with boxed milk, broke camp, and set off to return to Aransas Bay. The breeze pushed ARR & ARR at only a knot or two; the sail’s sheet drooped toward the water between the boom and the gunwale. A lone brown pelican swooped down and glided across the bay, so close that its shadowy reflection almost merged with its breast.

Four or five dolphins swam in close and surfaced in ones and twos. Some surfaced gently, as if half asleep; others, quickly and tightly arced, as if diving after fish. They’d swim off 100′ or so and then return. Once, while they were farther from the boat, one leapt completely out of the water. Each time they approached the boat, one would swim right up to my quarter, turn on its side still beneath the surface, and watch me watching it, and a couple of times, when they surfaced on my windward side, their exhalations misted my face.

The wind steadily grew, and just after noon I was sailing a good 4 knots in Aransas Bay back toward Mud Island. A sea turtle with mottled skin on its fist-sized head surfaced soporifically just off my starboard bow and then ducked back beneath the water with a plop.

I was all alone at a midday break at the cut through Mud Island, where our entire group had camped two nights before. These cuts and beaches are in constant flux. The spattering of olive green near the shoreline are hundreds of black mangrove seeds that have washed ashore. Given enough time between hurricanes or other storms, some will set down roots and make this spit of shell more permanent.

At the cut through Mud Island, I spilled the air from my sail and coasted to a stop as the bow growled into the shell beach. I pulled the boat higher on the shore, had an apple and an energy bar for lunch, and refilled my water bottles from my 3-gallon jerry can.

I thought I might be able to make it back to Goose Island State Park before dark, but I wasn’t sure. I knew, however, that I could make Paul’s Mott. I decided I’d rather be camping alone on an island than in the park in the middle of a row of RVs on the mainland. Opting for the park would also mean driving the boat through the waves on the leeward side of the bay, and crossing the ICW, and navigating through the oyster reefs, all possibly at the same time, and all likely after dark.

I walked the boat through the cut and set sail to close the distance with San José Island. In its lee, the waves were small, and I sailed on a reach with full sail in the freshening breeze. The wind thrummed the sail’s leech, and water gushed away from the hull in foamy surges. It was an absolutely thrilling sail.

On my final night of camping, at Paul’s Mott, Aransas Bay was calm. Jutting partially from beneath the tent, just below the door, is a 2′ piece of an old foam camping sleeping mat that I pull out and rest my knees on while working at the tent’s door, to protect my knees from the jagged oyster shells. I tuck the mat between the tent and the ground tarp when not in use to prevent the wind from carrying it away.

When I arrived in the waning evening light, Paul’s Mott was deserted, save for a few shore birds alternately skittering toward and away from the swoosh of wavelets on the beach, and a mockingbird singing from the highest limb of the point’s thicket of scrub oak, tanglewood, prickly pear, and other undergrowth. An undulating line of brown pelicans flying low over the bay crossed over the island and disappeared.

The shells that make up the point’s beach were so coarsely piled that when I tried to set the anchor ashore, even a light pull would drag it plowing through the shells and clanking down the beach. I finally set it in a bit of scrub, where the roots bound the shells together and held the flukes tight. For good measure, I pulled the boat as high onto the beach as I could and set a second line with a bit of chain at its end around the trunk of one of the little oaks.

The next morning, I woke before first light. A fat crescent moon high in the sky cast the tops of the clouds in a silvery light and left their bottoms a deep catfish blue. Between the moon and the clouds, Venus and Mercury flanked Spica, the brightest star in Virgo. The water’s horizon was a sprinkling of lights. Wavelets plashed occasionally against the shell shore, and the mockingbird chirped from within the thicket. The air was still but not stale, and a heavy dew soaked the tent’s fly. I had my coffee and oatmeal while daylight crept into the sky.

I casually broke camp and, as I loaded the boat, a powerboat of about 25′ motored leisurely to the reef just off the tip of the point. Two more soon followed. My first thought was that they were fishing charters, but they soon set to work dredging for oysters. The closest had a 6′-wide panel running from its port gunwale down into the water. Chains and machinery clanked and banged, and a dredge ground its way down the panel and splashed into the water, was dragged grumbling across the bottom, and then was pulled clanking and banging back up the panel, over and over. The boat’s engine clattered at just above an idle, and boom-box music with thrumming guitars, an accordion, and Spanish lyrics carried through the air. I was glad I hadn’t been trying to sleep when the boats had arrived.

After I had ARR & ARR ready to go, I still couldn’t feel any wind or see any cat’s-paws on the water. The forecast was for light wind and then calm in the afternoon, but I raised sail anyway. I pushed the boat into the water and, wading knee deep, walked it around the tip of the point so I could launch on the same side of the reef as the state park and wouldn’t drift near the oyster boats.

I pushed away from shore with one foot and clambered aboard. ARR & ARR moved 20 yards, slowed, and coasted to a stop. There wasn’t a whisper of wind. I put the oars in the locks and rowed away from the land.

After about a half hour of rowing, with Deadman Island nearly abreast and the ICW markers in sight, having already covered nearly a third of the distance to the state park and still with no sign of even the slightest breeze, I lowered the sail and set in to row the entire distance. I didn’t mind, really. Moving under oars is where ARR & ARR comes into her own—the Flint was designed primarily as a rowboat.

The row to the park turned into a hot one, with the sunlight glaring off the water as well as from the sky, and I paused often to wipe the sweat from my eyes. But I didn’t mind at all. I’d had everything from arduous rowing workouts to drifting lazily along like a mangrove seed to flying at hull speed on nearly flat water. I had enjoyed the company of friends, made new friends, and recharged in silent solitude. For such a disruptive year, the trip had been a perfect relief.![]()

Roger Siebert is an editor in Austin, Texas. He rows and sails his Flint on local lakes, and has trailered it to a few of his favorite places on the Florida coast.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Having sailed, fished and kayaked in all the locations you described so well, I once again had the pleasure of being there, if only virtually. Thank you for providing these pleasures for so many of us. Hope to see you around Austin.

[email protected]

Thank you, Bob.

What a great read. Thank You…

Thank you, John.

Thanks, Roger. I really enjoyed coming along on the cruise with you, and your lovely descriptions of the sights and experiences you had along the way. Was particularly interested to recognize your Flint and to hear how she performed along the way, as I built and sail another Ross Lillistone design, a First Mate, down here in Aotearoa/New Zealand. The waters you explored looked like great cruising grounds for boats like ours.

Tim H.

Thanks, Tim. The Flint is perfect for the area, as long as I pack lightly and keep an eye on the weather.

Very curious about Red Top! What a wild little boat.

Sounds like a lovely trip for a strange year. I’m looking forward to one of my own, soon.

Aransas Bay is my front yard. I can see Dead Mans Island sometimes with the nekked eye. I have a 1975 AMF 16ft Sunbird and never sailed it due to Harvey injuries, and the boat mast was destroyed in the hurricane. Your article has rekindled my spirit and my sea legs as well. I can walk pretty good now. After all I am related to the famous pirate Capt. Thomas Tew. That’s where I think I got me sea legs there matey. Keep in touch. I have a boat ramp across the street.

January 7, 2023, at 5:16 pm

Well, it’s two years since my previous comment. I just finished reading this story again and I have greatly enjoyed it once more. Thanks so much for sharing your experiences.