I have a shelf in the corner of my shop where I pile my collection of tape measures. They frequently fall off the shelf, and this past week I finally got tired enough of picking them up off the floor that I put them in order. In the process, I noticed a drawer in a small parts organizer that the tapes had been hiding. The drawer was marked “Knives.” The handwriting, in black Sharpie, was mine, but I didn’t remember putting any knives in that organizer. When I pulled the drawer out I immediately recognized one of the knives in it. “Oh, there you are,” I said out loud as one does when finding a member of the family in an unusual place in the house. It was my marlinespike knife, which had been missing for over ten years. The last time I’d seen it, I had taken it apart to replace the pins holding it together—they had loosened considerably with age. The knife had once belonged to my grandfather, Francis Cunningham, Sr.

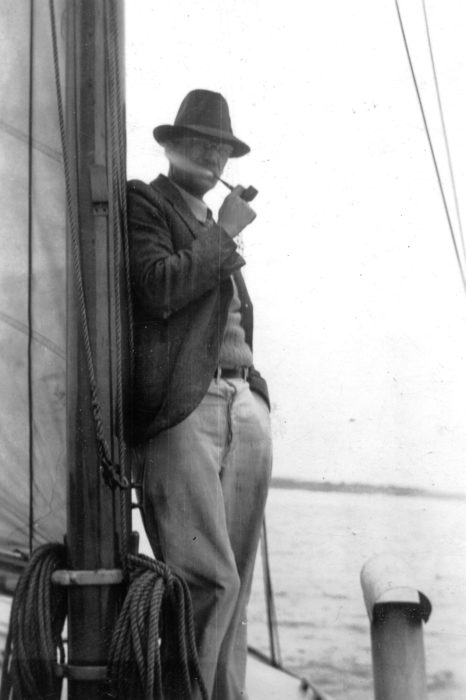

My grandfather, Francis Cunningham, Sr., dressed for sailing in an outfit that was at once natty and ratty.

My father, Francis Jr., was born and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts. Every two or three years we spent our summers in Massachusetts, splitting our time between my grandparents’ home in Lowell and a rented summer house in Marblehead, a harbor town just down the coast from Boston. On one of our stays back east we took a trip to New York City. I think it was in 1960; I was just seven years old then, so my memories of the trip are quite dim. I remember going shopping with my father for a birthday present for my grandfather, Papa, as my sisters and I called him. We went to Abercrombie and Fitch. It wasn’t at all like it is now, a source of trendy, upscale fashions for those who can afford to show a bit of midriff. It was the store for adventurers outfitting safaris and expeditions. I recall a high-ceilinged showroom with dark, wood-paneled walls covered with the mounted heads of African wildlife. Dad bought a folding marlinespike knife for Papa. We then visited FAO Schwarz, and Dad picked out a toy sailboat with a bright royal blue hull and a sloop rig. I liked it, and in my young mind I saw no reason that my 71-year-old grandfather wouldn’t like it too, as one of his birthday presents. As we were leaving, Dad asked me which gift Papa would like most; I could have the other one. I picked the knife for Papa and the sailboat was mine.

My grandfather’s boat, MOLLY MAY, was a 31′ auxiliary cutter designed by Wilder B. Harris in 1931. On hot summer days with light wind, Papa would trail a line from the stern so I could jump in the water and get towed behind the boat.

Papa would have used the knife for working on MOLLY MAY, the 31′ cutter he kept in Marblehead Harbor. After my grandfather died in 1965, Dad brought the knife home with him and used it working on his 27′ Tumlare sloop. In the ’60s, when I took an interest in maritime skills, Dad gave the marlinespike knife to me. Its blade held a good edge and was the best I’d ever used for cutting rope.

Eventually the knife got a bit loose and the marlinespike wouldn’t snap open and stay steady, so I took the knife apart, intending to fix it. I was at a loss for how to go about the repair and I put the knife away, in pieces. As it often is with important things put away carefully so they won’t get lost, I forgot where I put it. Having the knife once again in my hand, I straightaway set to putting it back in working order, using common nails to make new pins and replace the missing bail.

I sharpened the blade and, just as I remembered, it cut through rope with ease. I haven’t seen Papa for more than 55 years, but when I look at the knife, I imagine it held in the hand of my grandfather and think, “Oh, there you are.” ![]()

Putting the knife back together

The pins holding the wood covers to the liners hadn’t loosened so I had left those parts together. My goal was to make the knife functional again, not make it look like new. The knife had never rusted, so the steel had no pits and I could keep the patina of age.

I used two sizes of nails to make new pins for the knife. They were oversize, so I chucked them in a cordless drill and spun them against a fine sanding belt to get them to fit the holes in the liners.

The nail marked with the arrow presses against the two-ended spring to tension it. I couldn’t reassemble the knife with it in place, so I set it aside while I joined the liner and cover with the other pins.

With the pieces assembled, the pin that tensions the spring is driven in. It’s already seated here, marked by the arrow, with its point in a hole in the piece of wood under the knife. An extra tensioning pin, at left, shows the point beveled on one side. It functions a bit like a drawbore pin in a mortise-and-tenon joint, creating tension between the pieces being joined as it’s tapped in.

The beveled end of the tensioning pin is visible below the knife. With all of the pins in place, they can be trimmed and peened.

I kept the heads on the finishing nails I used for the new pins. That saved me from having to flare both ends of each pin. The belt sander took the extra metal off both ends of the pin. I left enough metal on the cut ends to flare them when peened.

The reason the knife loosened up in the first place was that the peened ends of the pin were pressing against wood, not metal (except for the blade’s pivot, run through metal bolsters on either side). I flared the pins wider than the originals had been to have a longer-lasting hold on the wood. My anvil is, I believe, a train car’s roller bearing, which I found by railroad tracks.

I used another nail to make a new bail. The original had been lost quite some time ago. The nail’s steel was soft enough to hammer cold to make the ends flat and wide.

After years of sharpening, the tip of the blade was no longer buried in the handle.

The projection on the blade’s tang is called the kick. It keeps the sharp edge of the blade from making contact with metal inside the handle. Trimming the kick on the belt sander will allow the blade to sit a bit deeper.

With the kick shortened, the blade is fully buried in the handle.

Peening the pin ends flared them, but they were shaped like the bells of trumpets and had sharp, proud edges. To roll the edges down and create mushroom-shaped ends, I used a diamond Dremel bit to shape a concave end on a pin punch.

A few taps of the modified pin punch rounded the rivet heads.

Back in good working order after serving the family for 60 years, my marlinespike knife is ready for future generations.

Love that sheepsfoot head on the blade, old school, similar to the knife we reviewed a few months back. Great looking knife with a wonderful story.

I love it when people refurbish useful items, like this knife. I always appreciate ceramic items that are glued back together. Like the knife, it means someone loved them enough to rescue them.

Well done!

R

Those are great memories or your grandfather, and to possess something that belonged to him is extra special.

Nicely done!

Wonderful story!

I have fond memories of my grandfather. I remember I had a sliver in my finger and he removed it with his pocket knife that he always carried. Great story, Chris.

This is great!

Absolutely beautiful. Restorations that preserve the history of an object and revive functionality are wonderful. The visual and tactile evidence of well-loved use combined with the family memories are all so special. Also, they really don’t make ’em like the used to.

I have some hand tools like a rasp, chisel or two, that belonged to my grandfather who died shortly before I was born in the 1950s. I know that part of the patina in those old wooden handles comes from the hands of a man I never knew. And somehow part of him lives on when I use one of these tools. Wonderful article.

A man after my own heart. It is so satisfying to be able to return to good use things that most people would consign to the rubbish pile. I particularly like your trick of beveling the end of the pin that bears against the tensioning spring.

Really nice, Chris. I hope the 4th generation can appreciate the nail bail!

I am sure that those of us lucky enough to able to be third- and fourth-generation tool users and or renewers know the deep satisfaction found there, and have pleasant memories sparked by this story.

Thanks!

Very satisfying project. Thanks for the tip on the kick. I need to stone the kick on my Dad’s old Case Doctor knife I keep alive using some of your techniques. It has lost about a half inch of blade length over the years from sharpening and the tip is beginning to become exposed. You do nice work.

Great story, thank you for sharing!

As a professional sharpener, I would recommend a rust eraser available from professional sharpening supplies. It will quickly restorer cutlery as well as hand tools.

Chris,

Delightful story, reminded me of Kintsugi, the Japanese art of putting broken pottery back together with gold. The idea is to embrace flaws and imperfections to create an even stronger and more beautiful piece of art. Your story made me go to my own “knife” drawer to see what I might resurrect from a lifetime of bosun’s knives. Well done, sir!

Thanks, Chris. I like to watch videos about restoring old, rusty tools to shiny, like-new condition, but I thought it best for the knife to look its age. The appreciation of flaws and imperfections you mention, as well as transience, are at the heart of the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, one of the things from my college classes in Zen that has stayed with me.

I love knife stories. My father’s rigging knife was a mid-century stainless type with a beautiful leather sheath but it did not stand the test of time. The blade snapped due to corrosion but I keep it in my desk drawer nonetheless for the memories.

That picture of your grandfather hollers loud the word “legend.”

Hi, Chris,

When I saw this article, I immediately thought about my own old rigging knife which I repaired in a similar manner probably 25 years ago. It’s a Wichard stainless knife with luminescent handles, originally riveted together with copper which failed after 10-15 years of use. I used short lengths of wire salvaged from coat hangers, which still hold the knife together fine and its still one I reach for when a knife is needed, but exposure to sea water has caused the steel pins to rust in place, so the knife doesn’t snap open as it used to any more, and the spring doesn’t work as firmly as it once did.

I guess you could look at this as a cautionary tale, if you wish. Enjoyed the article and the history as well.

Wandering back in the magazine, I found your article “Lost and Found” about rebuilding an old folding knife. I have the same knife, although in better shape than your original. I’ve had it many years and probably bought it Port Angeles, Washington, in 1966-1967 when I was stationed at the Coast Guard Air Station there. At some point I chipped out a bit of the wood, but no matter, it works well and loves being in my tool bag.

Great story! My Grandfather died when I was in junior high. I kind of knew him, but I didn’t really know him. Now the beautiful pocket watch that he carried hangs on my desk. The first thing I do every morning is wind that watch. Out in the workshop I have several tools that belonged to him, and I use them often. A tack hammer and a set of three squares, with wooden stock and steel blade, are the tools I use most. I also have a couple of his wedges for splitting firewood. I make it a point to take a few swings at them every year, even though most of my wood is split with hydraulics. The only time I ever saw him was at family gatherings, so it’s interesting to imagine what his day-to-day life might have been like. Thank you for sharing this story.

This is one of my favorite articles I’ve read in Small Boats, a perfect blend of how-to and nostalgia.