Benjamin Mendlowitz

Benjamin MendlowitzNathanael Greene Herreshoff designed the original Coquina for his own use. Excellent balance and sailing characteristics—and above all, simplicity—made the 16’8” LOA boat one of his favorites.

It can be a bit difficult sometimes to get beyond the mystique of a great yacht designer’s hallowed reputation, never more so than with Nathanael Greene Herreshoff (1848–1938). “Genius” is appended to his name as routinely as it is to Mozart’s. It’s best, if you can, to try to forget the history surrounding such a designer’s boat—like trying to listen to a famous string quartet as if you were hearing it for the first time. Instead, get inside his mind by using the boat plainly and simply for what it was meant to do. And when it comes to N.G. Herreshoff, no design makes that easier than a Coquina.

Like all of Herreshoff’s designs, formal lines drawings never existed for this 16’8″ LOA hull because he measured his own half models to develop tables of offsets that he handed directly to his yard’s boatbuilders for lofting the hull full-sized. The Herreshoff Mfg. Co. built the first boat of this design in 1889 for Herreshoff’s own use, and only one other was built in the designer’s time.

The absence of lines drawings has complicated replica construction in the modern era for any but the most experienced builders, who have had to analyze papers and photographs in the Hart Nautical Collections at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Museum—MIT being Herreshoff’s engineering school alma mater and its museum the custodian of the Herreshoff company’s drawings and offset tables. However, several years ago boatbuilder and designer Doug Hylan teamed up with this magazine’s technical editor, Maynard Bray, both of Brooklin, Maine, to develop a detailed building plans package for the boat (see also WoodenBoat magazine No. 187).

“Regardless of whether the boat is built in plywood or the traditional cedar, sailing a Coquina is an undoubted pleasure.”

Working under license from the MIT Museum, they based Doug’s drawings on Maynard’s research. But they also added extensive detail and instructions to bring the boat within grasp of talented amateur builders. The resulting plans are uncommonly well detailed, running to 11 sheets, specifying either traditional planking or glued-lapstrake plywood construction, all supplemented by an instructional CD with 550 photos documenting the construction.

I had seen Coquinas under sail and at rest many times but never sailed one myself before scheduling an outing aboard WIZARD with Vagn Worm. Vagn has a summer place on the Benjamin River neighboring the D.N. Hylan & Associates yard, where the pieces for WIZARD were assembled. Doug not only sells plans but also builds completed boats, bare hulls, and kits like the one Vagn purchased. Vagn was looking for a daysailer to take advantage of the afternoon breezes he could see from his porch, and he quickly settled on a Coquina, having seen the first two boats of this design come out of Hylan’s yard.

Building this boat, no matter what method, would be a real joy. The planking lines are a pleasure to look at, and instead of the careful lining-off that would be required in building from original plans or tables of offsets, Hylan’s plans specify plank locations at each mold. He also provides specific layouts for each individual plank. With the boat’s fine, easy lines and its thin planking stock, the work should go very easily and pleasantly. The masts and spars would present some opportunities for working with fine stock—the boat is crying out for varnished clear spruce spars—but the quantities involved would not be so large as to be completely ruinous to the bank account. Careful attention to detail and to finishes would yield a stunning result, whether in traditional planking or plywood, bright-finished or painted.

I’m aware that most people would likely choose plywood planking these days, for easy availability if nothing else. For my money, though, I would go with traditional cedar planking. It would be a great pleasure to run those gently curving plank edges with a hand plane and work in the “gains” at the plank ends with truly sharp edge tools to fit perfectly in the stem rabbet. Such work on a lapstrake boat is one of the great joys of life. The result would probably be heavier than a glued-plywood construction, but in my view ever-lighter weight as a holy grail of boatbuilding is highly overrated.

Thinking of building a Coquina of your own? Check out this Reader Built Coquina for some inspiration.

Regardless of whether the boat is built in plywood or the traditional cedar, sailing a Coquina is an undoubted pleasure. In our first outing, Vagn and I were slammed by a dark-souled squall line carrying something more than 25 knots of wind with it. We got the rig down in a hurry and I took to the oars, barely able to make headway against the wind and waves of some 3′. Though the boat never felt in peril, with a lee shore looming we ultimately took a tow from a neighborly lobsterman.

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonVagn Worm keeps his kit-built WIZARD on a mooring, so all he needs to do after an afternoon sail is tend the sails and raise the centerboard. To furl the mizzen, he rotates the boom all the way forward for easy access.

A break in the weather for our second attempt a week or so later gave us a pleasant late-August breeze of about 12 knots and mostly sunny skies—a picture-postcard day tailor-made for this boat, it seemed. For the new guy—me—it would have been nice to have had this weather in reverse, with the pleas- ant day as a warm-up for the screaming banshees later.

Making sail is uncommonly easy in a Coquina. Both main and mizzen are gaff-rigged. Hauling the throat and peak halyards together (mizzen first, then main) takes the gaff aloft level to the waterline until the luff is taut. After making off the throat halyard, you peak up the gaff until a crease shows in the sail from tack to peak, then make that halyard off, too. Vagn brings his mainsheet aboard through a swiveling cam cleat mounted on the centerline of the after thwart.

The mizzen sheet reeves through a cam cleat mounted on the forward edge of the afterdeck, a little to port to clear the mast. Granted, the masts were already up and the boat was already at the mooring when we embarked, but the setup was as easy as taking off the sail stops, lowering the centerboard, raising sail, and casting off. This boat’s hull form, however, clearly would make the alternative of launching from a trailer very simple. Without stays or shrouds, the mast and rig setup wouldn’t take much longer when trailer-launching than it does at the mooring. The rudder is not so deep that it would have to be removed—depending on the trailer setup and the con- figuration of the launching ramp, of course.

Without doubt, the steering system is the most unusual aspect of the boat. In the design specifications, one line per side is made off to the rudder and reeves through a fairlead “beehole” in the transom. This line then operates through a three-part mechanical advantage under the afterdeck and then passes through a fairlead beehole in the after bulkhead. Then it runs through fairleads under the narrow side decks. The ends of these two lines are spliced together to make a continuous loop running around the interior of the boat. Some prefer to have the line cross the hull at the forward thwart, but others take the line all the way to the stem, as Vagn chose to do.

However the steering line is led, this system isn’t uncommon (see our Beachcomber-Alpha dory profile for a variation on the concept). This one, however, does present some differences. For one thing, you can’t see the rudderhead, so checking whether the rudder is amidships has to be done by feel. Now, there’s nothing wrong with this—I’m a great advocate (to my wife, crew, and anyone else who might be listening) of sailing and steering by feel more than by indicators of one type or another. I believe this is the best and most thorough way to learn a boat’s characteristics, and this boat would teach you well and quickly. But this steering system does take some getting used to, and I would probably always miss a tiller, with its continual feedback about exact rudder angle.

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonCoquina steers by a continuous line attached to the rudder, and in this case the line passes through fairleads under the side decks all the way forward to the stem. Blocks giving three-part mechanical advantage are hidden under the afterdeck. Molded sheerstrakes are one design detail the daysailer has in common with larger Herreshoff yachts.

During our first outing, while Vagn and I had to get the rig down in the blow, the boat slipped backward, pushing the rudder to one side and hard against the transom. In this state, the steering lines don’t have sufficient leverage to bring the rudder back amidships— you’ve got to either reach over the transom to give the rudder a push by hand or start rowing to gain enough steerageway for the rudder to start its swing. In 3′ seas, it took considerable effort at the oars to get up the necessary speed.

I would think that stopper knots in the steering line set to ride against the bulkhead fairleads might prevent this from happening, with the benefit of also preventing oversteering during tacks. Some sort of an indicator in the line—one whipping per side referenced to a known location, such as a knee, for example— might give a quick visual check to see when the rudder is amidships. For someone new to this system, turning the wrong way is a problem relatively quickly overcome, but getting a feel for how much to steer takes longer. Eventually you settle on the right amount of tension to keep on the line to counteract the boat’s slight weather helm, neither pulling the line nor easing it too much as the boat reacts to the seas. It’s a little bit like playing a fish with a rod and reel.

In 12 knots of breeze, the boat was perfectly at home, with an easy and highly responsive motion. Vagn compares the boat’s handling to a racing dinghy, often needing crew weight on the weather rail to keep her on her feet, despite the fact that he keeps 50 lbs of inside ballast under the floorboards. (For the record, Herreshoff himself recommended 140 lbs of inside ballast.)

The very low coaming capping the side decks makes it easy and comfortable to hike out when necessary. One benefit of the loop steering system is that a solo sailor can be well out on the weather rail and still reach the steering line. Also, he can adjust weight forward or aft, or he can move around the boat as needed to adjust a downhaul or halyard, prepare an anchor, reef, or grab his lunch, and all while still being able to steer. Those are excellent advantages.

I found it very easy to “read” Coquina’s sails. If you are pointing a hair too close to the wind, the balance response is immediate, so it’s easy to find the sweet spot. When you do, her speed picks up noticeably. If you go too far off the wind without easing the sheets, her stall is also readily perceptible. This makes it very simple to feel when the boat is on the knife-edge of efficiency and when it is being headed or lifted by variable breezes.

Coquina is well-suited for solo cruises as well. Read of one Adventure from The Isles of Finland.

She seems to point very well to windward. Tacking is effortless. Really, nothing needs to be done—just put her over and find the new tack based on sail trim. When jibing, all you need to do is haul the mainsheet and then let it run out gently to the new trim. The mizzen takes care of itself. The boat seems to settle very nicely into wing-on-wing sailing, making that often-troublesome point of sail easy to hold—which can’t be said of all boats. When jibing the mizzen, I found it simple enough to just reach aft, grab the boom, and push it to the other side, restraining it a bit to prevent shock loading. Her split rig gives her excellent balance downwind.

The boat is set up with one rowing station, but in my view this boat is all about sailing—rowing isn’t particularly easy or enjoyable and merely gets you home if the wind utterly fails. With her 130 sq ft of sail, lean shape, and great all-around handling, she promises to move well in light air. The oars would be the last resort on a day of the faintest breeze or a bothersome current.

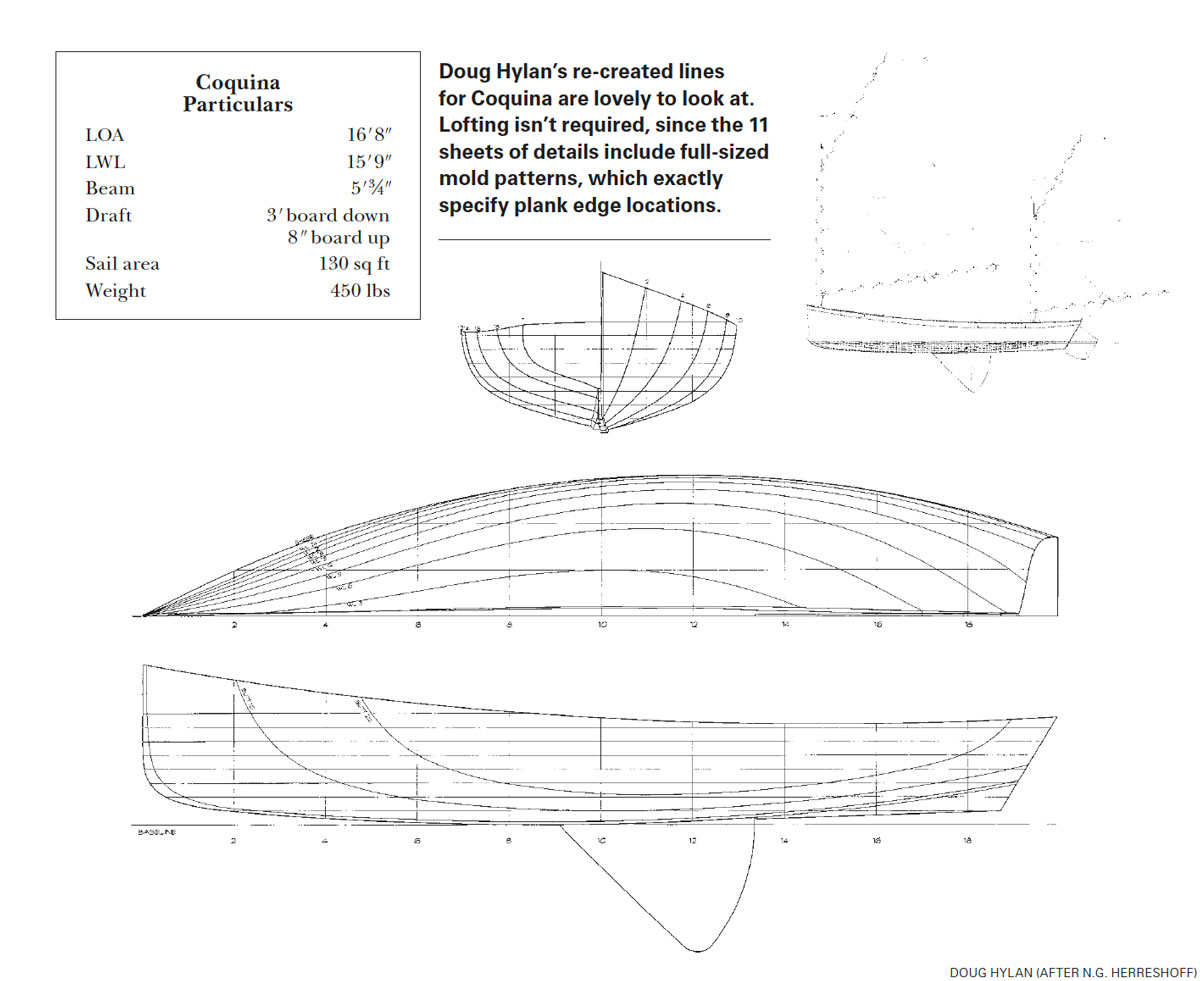

Doug Hylan

Doug HylanDoug Hylan’s re-created lines for Coquina are lovely to look at. Lofting isn’t required, since the 11 sheets of details include full-sized mold patterns, which exactly specify plank edge locations.

When he was up in years, Herreshoff recalled that this diminutive daysailer was the boat he liked to use more often than any other during his lifetime in spectacular boats. In a way, this is not surprising, since it seems to be a universal law that the amount of use a boat gets is inversely proportional to its length. But Herreshoff had boats galore and access without end, so his fondness for this particular daysailer had to have been heartfelt.

The original boat was delicately built—with only 5⁄16″ cedar planking—by one of the best craftsmen at Herreshoff Mfg. Co. For decades, it was kept in davits in a boathouse adjacent to Herreshoff’s Love Rocks home in Bristol, Rhode Island. He used it often, in every season, even on fine winter days. His equally famous son L. Francis wrote that COQUINA was the first boat he could remember sailing in. The boat, sadly, was destroyed when the boathouse was carried away by the famous 1938 Hurricane that devastated New England coastlines.

Boats that designers create for themselves, free from influence of racing rules, client demands, or market expectations, offer unique insight into the designer’s thinking. Sailing a boat that N.G. Herreshoff liked so much and suited his needs so well inspires respect that can take you directly to the root of why he attained his resilient and enduring fame. It really is like hearing a Mozart concerto for the first time.

D.N. Hylan & Associates, 53 Benjamin River Dr., Brooklin, ME 04616; 207–359–9807

The MIT Museum, Hart Nautical Collections, Building N51, 265 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge, MA 02139; 617–253–4444

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.