Two years ago, when I was considering building my next sailboat, I daydreamed about a compact, shoal-draft solo cruiser with a comfortable cabin that has no need of an engine. My sailing in recent years involved cruising and racing my trimaran, sometimes in very lively conditions. That boat was all about speed and distance. Perhaps I’m getting old and lazy and even a bit cranky, but no more jibs, no more winches, no more twangy-tight shrouds for me. I’d had enough of fooling with the noise and maintenance of engines and the careful timing and physical effort that sail rigs demand simply to change direction. I wanted to revisit the low-key end of the boating spectrum, gunkholing the shallow and protected places that few cruisers visit.

I had expected there would be a good list of production boats to fit the bill, and an even greater selection of plans and kits for the home builder. But no, my search was a frustrating one until I recalled seeing Chesapeake Light Craft’s Autumn Leaves in WoodenBoat No. 249. It was not just a boat that I could make work for what I had planned, but one that John Harris had drawn from scratch for exactly this purpose. Add to that the availability of a CNC-cut plywood kit and a timber package milled of quality stock, and my decision was all but made.

David Dawson

David DawsonThe Autumn Leaves has a towing weight of about 1500 lbs. and doesn’t require a large truck to pull it. The Volvo here has a towing capacity of 3,300 lbs.

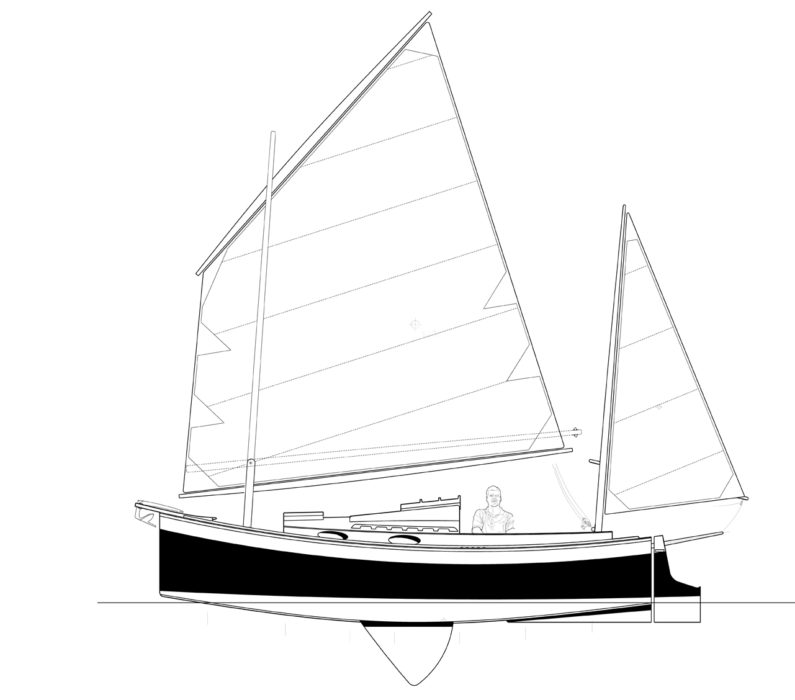

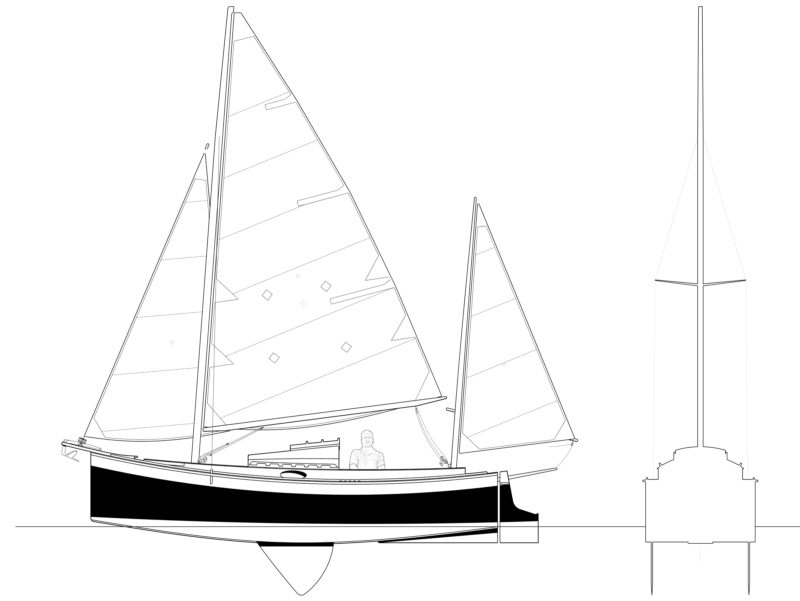

At the time I had read Mike O’Brien’s comments about the design in WoodenBoat, no one had built an Autumn Leaves, but I was quite intrigued by Mike’s assessment of the drawings. While he noted the rig—a classic yawl with a jib— “will prove a joy to handle,” it seemed the three sails might be a bit fussy for me in an 18′6″ boat. A few years ago, I turned a 16’ skiff into a balanced lug yawl and found it most agreeable, and knew this rig was the right direction to take. I was downsizing from that larger and fairly complicated trimaran and wanted to simplify everything as much as possible. I wrote to John and asked if an Autumn Leaves could be built with a balanced lug main in a tabernacle. John agreed and drew the new sail plan and at the same time extended the cabin trunk to create a more agreeable interior. With that, I placed my order.

Putting the hull together was straightforward. Chesapeake Light Craft cut the kit for me without having put a prototype together—the first time they’d done this—but I was game to be the guinea pig. The plans were detailed, but a step-by-step construction manual had not yet been created. I received countless tips from John as I worked my way through the build. The precision of the CNC okoume parts was a marvel. I found just one very minor measurement error in the entire kit. I also purchased the Autumn Leaves timber- and spar-stock packages. The quality of the lumber was far beyond anything I could have sourced locally, and because the stock was milled to the finish width and thickness, I saved many hours of work sawing, resawing, and planing.

Caroline Dawson

Caroline DawsonThe auxiliary power is provided by a pair of oars rowed while standing and facing forward.

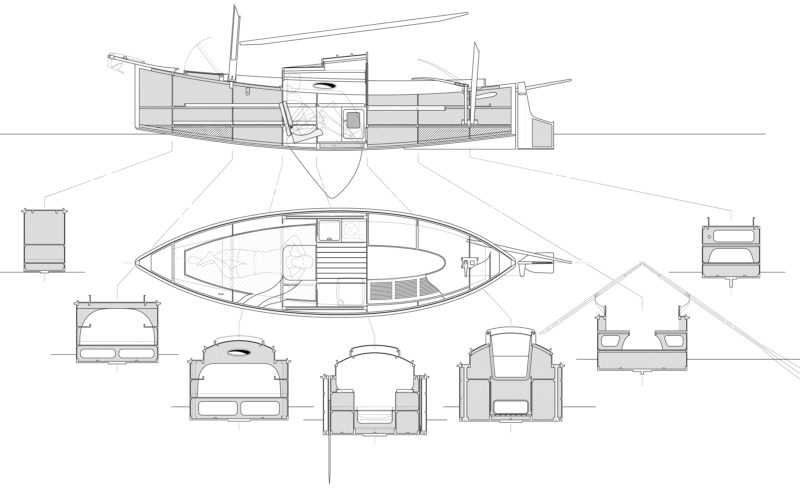

The specs for Autumn Leaves create a very stout hull. The bottom is composed of two layers of 9mm plywood with a third strip of 18mm ply down the center, forming a wide, flat keel. Generous placement of cleats and stringers tie bulkheads and horizontal plywood members together to create a very rigid structure. In the ends of the boat, below the cockpit sole aft and berth flat forward, foam provides about 860 lbs of flotation. This plywood boat does not resonate like a drum, often a problem with the type. The exterior surfaces are sheathed in epoxy and fiberglass. I had the aluminum tabernacle for the free-standing main mast fabricated by a local shop.

The plans call for 14 ballast castings of approximately 38 lbs each, or 532 lbs total. The mainmast and tabernacle structure on the lug version is heavier than the deck-stepped, stayed mast on the original version. To compensate for this, John suggested that I add extra lead, bringing the total up to 620 lbs. Making the castings was the only process I’d never done before, and so was the biggest challenge of the build for me. Others may be intimidated by having to melt and pour lead, but those familiar with the process said it’s not really difficult. My view is that going with lead is preferable to the alternative. Building a water-ballasted boat adds another step to the launching and retrieval at the boat ramp.

courtesy of Chesapeake Light Craft

courtesy of Chesapeake Light CraftThe box-section hull has a beam of just 5′, but lead ballast in excess of 600 lbs keeps the hull on its bottom while under sail.

Fifteen months after picking up the kit from CLC in Annapolis, Maryland, I had my Autumn Leaves in the water. The boat immediately surprised me with a surefootedness and ease of motion that I did not expect. The slab-sided hull has just 5′ of beam, but motion is tempered by of the lead ballast under the floorboards. It feels in every respect like a bigger boat than it is.

I’m more than pleased with the ease of raising the mainmast in its tabernacle without assistance, setup rigs, or tools of any kind. Both the main and mizzen sails remain laced to their spars. The mizzen bundle is light enough to lift and simply drop straight through its partner. The bilge boards are housed in cases that open to the side decks. They are not ballasted and pivot up and down with very little effort.

The Sitka-spruce mainmast, boom, and yard are of lightweight, hollow box-section construction, and the masts are unstayed so it takes little effort to rig the boat and raise sail. The mizzenmast and its sprit are solid, but are small enough to be easy to handle. The 180 sq ft of canvas the boat carries in the main and mizzen is plenty; even in the lightest airs, it ghosts willingly and easily. As the wind picks up, weather helm predictably builds, and feathering or even dousing the mizzen and trimming up the boards will reset the balance.

My first real outing in a strong wind had me concerned on this point. A tailwind of 25 knots and a steep, breaking Chesapeake Bay chop that reached 4′ high forced yawing beyond what the shoal-draft rudder could control, despite its generous endplate. But adjustments since then—setting the sail more forward on the mast and lifting the boards partway—have shown that in most conditions the boat is fine as drawn. For sailors who regularly have to navigate rougher conditions, John has sketched a rudder that encloses an aluminum drop plate to increase its depth and area when needed. I may make one, but rougher conditions are not what I have in mind.

Cie Stroud

Cie StroudThe lug rig carries 150 s ft in the main and 30 sq ft in the mizzen for a total of 180 sq ft, just 7 sq ft less than the alternate rig with the same mizzen, a 114 sq ft Bermuda main and a 43 sq ft jib.

The suitability of the Autumn Leaves design to the dedicated gunkholer is obvious at a glance. It draws just 8” with the boards up and has no appendages to catch weed or pot warp. This was brought home to me on a very blustery day at a local lake. It was time for lunch and I wanted to get out of the wind and relax. I sailed deep into a tree-lined cove, close to the shoreline. The water was choked with weeds. No problem, I doused the sails and let the anchor go into the green mass. So close to shore, the wind was down to nothing and the October sun was quite warm. After I ate and rested, it was an easy drill to raise the anchor, set the sails, give one sweep of an oar to bring the bowsprit away from the overhanging branch it was nuzzling, and off we went. As soon as I cleared the weeds, I put the boards down. Catching the breeze beyond the shoreline’s wind shadow, the boat bounded down the lake.

When I first sailed the boat, I found it easy to greatly underestimate my speed until I consulted the GPS. The skinny hull does not toss the water around much, removing the noise and visual clues that usually suggest speed in a boat this size. And if the reefs are tucked in when due, the Autumn Leaves stays on its feet, giving the crew nestled in the deep cockpit a sense of solid security.

David Dawson

David DawsonThe cabin isn’t large, but it has a comfortable chair that folds down to create a broad sleeping platform for one.

Simplicity extends to life aboard the Autumn Leaves. When it’s time to settle down for the evening, John made sure the solo cruiser would have ample comfort. In the center of the cabin is a cushy easy chair, just right for reading. It’s folded and hidden under the end of the berth when not in use. Countertops are right at hand near the companionway, with camp stove to one side and navigation gear to the other. Everything is within arm’s reach. The cabin overhead is low, but the average person can sit on the forward end of the berth flat without butting up against the roof, and there is space enough to stow and use a portable toilet or bucket, as one prefers. One compromise I made in opting for the unstayed mast is an obstruction about a foot back from the forward end of the cabin—the tabernacle comes through the deck and the berth on its way to an anchoring cross-member on the hull. There is good headroom forward, thanks to the extended trunk, and to my surprise I found it wasn’t difficult to crawl out through the hatch at the forward end of the cabin roof. Storage in the cabin is generous, with lockers under both the berth flat and the cockpit sole.

courtesy of Chesapeake Light Craft

courtesy of Chesapeake Light CraftThe designer recommends putting the first reef in when whitecaps appear.

Three can be comfortable in the cockpit for a day sail, but for overnighting, Autumn Leaves is a one-person cruiser. And the solo sailor does need a bit of determination to go without a motor. The boat has a good deal of windage and, loaded for a week’s cruise, it displaces over a ton. It rows easily in a calm—I can maintain 1.5 knots with minimal effort, 2 knots if I push hard—but once the wind is much over 5 knots, the boat needs to be sailed to make good way.

John told me he was aiming for an L. Francis Herreshoff Rozinante-type of boat that would be easy and affordable to build, a canoe yawl in the tradition of Albert Strange and friends, an engineless sailboat for cruising as it was once always done. I think he hit the mark. I christened my Autumn Leaves TERRAPIN, after a turtle once common up and down the East Coast of the U.S., and with her I’ll be gunkholing the shallow and protected places that few cruisers visit: the backwaters, creeks, rivers, and estuaries along the Mid-Atlantic coast.![]()

David Dawson is a retired newspaperman who has been hooked on boats since he was a boy, when his dad built a plywood pram. He does most of his cruising on the Chesapeake Bay, but has taken a variety of trailerable boats elsewhere to explore waters from New England to Florida. Nearer to home in Pennsylvania, he enjoys kayaking the local rivers, lakes, and bays.

Autumn Leaves Particulars

[table]

Length/18′5″

Hull weight/1,500 lbs

Beam/60″

Max payload/2,200 lbs

Rowing draft/8″

Sailing draft/37″

Sail area/Yawl 187 sq ft; lug yawl 180 sq ft

[/table]

Plans ($45) and kits ($3324 for plywood parts) for the Autumn Leaves are available from Chesapeake Light Craft.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I am beginning to think that Phil Bolger’s boat philosophy is beginning to really catch on. Boats with an open mind indeed! Wonderful work, David!

Rob

Hi David

I owned a Bolger Old Shoe, a 12′ flat-bottom yawl, a similar concept to Autumn Leaves. Just loved it. I beach cruised through the Whitsunday Islands on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef for a couple of months in 1980 in her. What a capable little ship.

Autumn Leaves looks similar. She is great looking and should be even more capable than Old Shoe was. Great job on the construction and good to see you stuck to the designer’s plans.

Happy sailing,

Jim D.

I saw TERRAPIN at the Mid-Atlantic Small Craft Festival this past October. The weather was truly frightful and my small boat stayed firmly tied to the dock while the Autumn Leaves was out playing in the wind. She is a lovely design, finished well. Thanks for bringing her out

Nice work on the build. She looks versatile and fun, ready for a mess about. Thanks for sharing your story.

Kent

It’s not that I dislike Bolger’s designs, they just look odd. In spite of that, I have built two of them, a Bolger Bobcat and a Gloucester Light Dory. Both excellent handling craft. Great job building the Autumn Leaves!!

And I built and sailed a Bolger Martha Jane. This boat reminds me of a nicely downsized MJ. Once the Martha Jane ballast was increased to 1000 lbs, she was a formable sailer. With 600 lbs of ballast Autumn Leaves should be really steady. I’m really impressed!

Jim, John Harris built an Oldshoe for himself some years back, and that boat was one of many influences on the design of Autumn Leaves.

Steve, I bought plans for the Martha Jane back in the ’80s, but never built the boat. Autumn Leaves is definitely a similar concept, scaled down for the solo cruiser. So building TERRAPIN brings me back to what I was thinking of doing some 30 years ago. I’m really impressed by how unboxy this “box boat” looks once in the water and under way. There’s some real design sleight of hand involved in achieving this.

I have just finished my Bolger Chebacco, a long and slow process. I have yet to sail it, but looking forward to spring. I think Steve was wise to build “unpowered” because the Pennsylvania certification requirements are beyond reach for a homebuilt. I have a great deal of respect for many of Bolger’s designs and it is good to see others recognizing the attributes. Very nice job on the boat, enjoy it.

Richard,

Pennsylvania has gotten very confusing when it comes to homebuilt boats. I did request an unpowered registration, but they gave me a powered sticker. But, either way, my CLC kit project made an important difference. If you buy a kit rather than build to the plans, CLC will provide a certificate of origin as builder of the boat. So the boat, although assembled at home, can be registered as a factory-built craft from Annapolis, Maryland. In Pennsylvania, this is an important difference. New state rules outlaw the sale of a homebuilt boat. I really like the Chebacco, too. That was on my short list before I went with the Autumn Leaves.

I also saw TERRAPIN at the 2019 Mid-Atlantic Small Craft Festival. It was blowing hard enough to blow my ball cap off while cruising the docks. Got a picture of TERRAPIN while dropping the main and getting ready to anchor. David made it look so easy! Nice boat.

Comfortable seat in cabin is excellent feature. The Montgomery 16 Kat Bote, is another good example of a comfortable cabin seat on a small boat.

The TERRAPIN seat is in best position, centered looking out the companionway.

Dave,

I beat you into the water by only a few weeks, but you really beat me by a lot when it comes to finish. I am in the process of having a custom gaff mainsail designed and made for INDIGO. I am still considering the appointments for the cabin while you are already sleeping in TERRAPIN. Thanks for the video by the way. Congratulations on a job well done. Maybe we might be able to sail together one day.

Al

Thanks, Al. It would be great to sail together at some point. When a few more Autumn Leaves get built, maybe we could set up a national meet.

Way back in 1966, I bought a Lone Star 13, a beautiful little masthead sloop designed by Thomas Faul and Charles Wittholz. I fell in love with it as I was learning to sail in a Philip Rhodes designed Penguin. It had a beautiful sheer line and enough hollow in the bow sections to curl a wonderful bow wave. I traded the Penguin in on an LS-13 after only a month and learned that its other great feature was lever-action bilgeboards. I no longer sail, but I still love sail boats and I’ve wondered over the years why bilgeboards aren’t used more often.

It took me a while to learn to get the most out of the LS-13, but once I did I could sail it competitively with Flying Dutchmen Jrs. I sailed it on Texas lakes and rivers (the San Bernard and the Brazos) and through the surf in the Gulf of Mexico. One of the biggest mistakes I ever made was selling it because my wife wanted a boat with a cuddy cabin. We bought a Luger Leeward kit boat that my dad had built. It was OK, but never captured my heart the way the LS-13 did. 🙁

Hi David,

Beautifully constructed and the video is convincing. Am sorely tempted to order the CLC kit this weekend. I live in northeast PA. If there’s any way I could visit your TERRAPIN, I would be much obliged. Have built the CLC Skerry and as such have become a believer in the balanced lug rig (Skerry). Autumn Leaves has sitting room and countertop space, as well as the built-in capability for rowing – all plusses for coastal cruising and gunkholing. Thanks for your well-written article!

Brad

David,

Thanks for sharing. I’ve admired AUTUMN LEAVES since John first talked about her on the CLC site. Your piece sure brings her to life for me. You’ve done a wonderful job building her. Love the lug-yawl rig.

John is an artist with a practical streak. I’ve been enjoying his Peeler Skiff design on Narragansett Bay since we built her in 2014. She’s an impressive combination of engineering and functionality and I was very pleasantly surprised by how pretty John was able to make a flat-bottomed skiff.

Cheers,

-Dick-

What model Load Rite trailer? I will be finishing an Autumn Leaves this year.

Ron