I first met Phil Thiel in 2009. My son Nate had just graduated from high school and was eager to build a boat, so we decided upon Phil’s 18′6″ Escargot canal boat. We paid a visit to him at his home, only a half dozen miles from ours, and he led us to his basement shop where he had his stock of plans, all stored in cardboard tubes. Over that summer, I coached Nate and his friend Bobby through the build and kept Phil up to date with the progress.

I continued to keep in touch with him after BONZO, a slightly modified Escargot, was launched in October. Phil was ill, with no hope of recovery, so I visited with increasing frequency, offering to help in any way I could; I had several of his plans sets scanned so they’d more easily made available. I had lost my father suddenly the year before, so I knew how important my remaining time with Phil would be. When I was offered this job, working with WoodenBoat as the editor of Small Boats Monthly, I knew how happy that my father would have been for me, but he was gone. I told Phil, and I got the smile I needed from him.

I was with Phil, his family, and a few friends when he passed away on the evening of May 10, 2014. Since then I have had the privilege of visiting Phil’s shop and have kept in touch with his family—wife Midori and children Kenji, Tamiko, and Kiko. It is with their kindness that I can share a few glimpses of my absent friend.

You could say Phil’s shop is “organically” organized. His tools and materials aren’t separated into categories, they’re intertwined like the roots of a tree, and the juxtapositions—waxed paper, an old brass scale, and a padlock, or tarred marline, a trailer ball, and toothpicks—have an engaging, even poetic quality.

Over his home’s front door, there is a sentence, one of many written in all caps in white chalk on the dark exposed ceiling beams, that reads: “A LOT OF WHAT I DO GROWS OUT OF WHAT I’M DOING.” The shop fosters that sense of unexpected possibilities and is fertile ground for the imagination.

Phil bought this machinist’s lathe, used, on November 24, 1987. It’s a South Bend C9-10JR, manufactured in South Bend, Indiana. Its original owner purchased it in 1949. The headstock needed some work and a few parts were missing, so Phil wrote to the manufacturer on January 9, 1988, beginning with:

“Ladies and Gentlemen, I have recently achieved a life-long ambition and at age 67, a few weeks before retirement from teaching, acquired a South Bend Lathe.”

The motor, here hidden from view, delivers power to the lathe with a flat leather belt, seen on a three-step pulley.

For woodturning projects there is a small lathe driven by a motor mounted underneath the workbench. Here, it has a sanding disc attached to the headstock and a wooden table on the tool rest. His daughters have fond childhood memories of spending time in their father’s shop using this lathe.

The anvil was made from a section of railroad track and fastened to a short timber. It was portable and could be set on the basement’s concrete floor rather than a workbench, which would bounce and rattle everything else on the bench top.

The pedal drive in Phil’s Sanpram required a propeller specifically designed for modest power and a peddler doing about 60 rpm, so Phil designed a wooden prop of stacked plywood. The pattern for the plywood rests on the workbench. Stair-stepping the pieces according to the marks on the paper pattern creates the proper pitch. The long cone on the finished prop reduces drag.

Phil made a lot of paper models as he developed his designs. This one appears to be the 22’9″ Joliboat. He used a similar angled roof as an option to provide more headroom in the L’Ark version of the Escargot. The drawing below is a freehand sketch of the 22’9″ Friendship.

Phil kept busy right up to his last days. This is his desk as he left it. I haven’t been able to figure out what his last drawing was about.

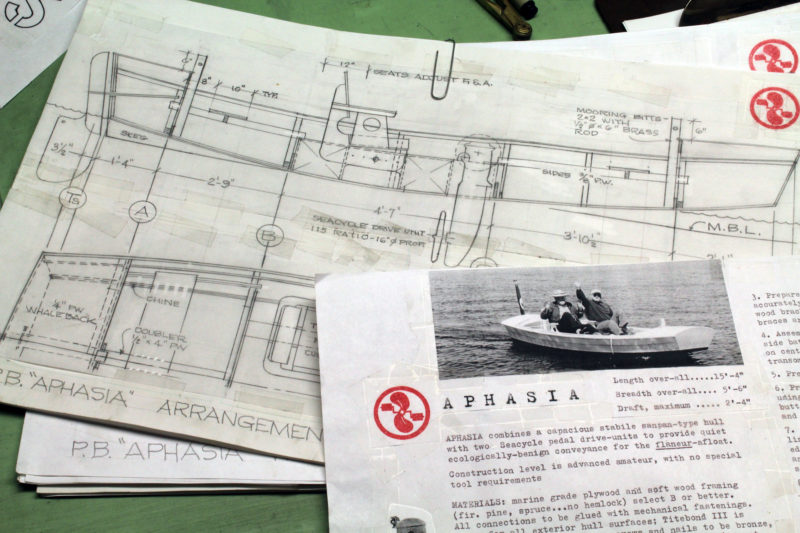

For all his technical prowess, Phil never went digital with his work. He did all of his drawings by hand, inked them flawlessly, and then taped pieces together to make masters to be photocopied. The year before he passed away, I took the originals drawings for his small wooden boats to a copy shop and scanned them. The digital files will assure the survival of his work and make his boats more easily and widely available.

The red stamp has a propeller and bicycle pedals joined and set inside a circle. It’s an indication of Phil’s interest in Japanese culture. In Japan, a Kamon is a symbol of one’s clan and has been used since the 12th century. It’s like a European family crest but with a broader set of relationships. Designs in circles are a common form of Kamon.

Phil had another circular symbol—a snail, set on ripples of water, with SERENDIPITY written in an arc to complete the circle. His serendipitous snail is a reminder to go slow while boating and to leave yourself open to chance.

Sitting on ledge near the drafting table is a stack of paper models: a tombstone-transom dory at left and a double ender sitting in a pram at right. The two long models at the bottom are for the 15′ 7″ Skiffcycle, one of the smallest of Phil’s “pedal-powered boats for the flâneur-afloat” and designed for a commercial Sea-Cycle drive. Phil’s graph plotting boat speed and pedal rpm shows the Skiffcycle reaching 5 1/2 mph, though Phil, a flâneur himself, wouldn’t dream of rushing about at such a pace, missing all of the sights, sounds, and scents to be taken in at a more leisurely pace. On at least one occasion, he furrowed his brow when I told him I usually paddled my kayak at 6 mph.

Models for the 15′ 4″ Aphasia (left), designed in 2006, and the 12′ 4″ Sanpram, designed in 2011, are resting on drawings for the Escargot. The Center for Wooden Boats in Seattle has had the first-built Aphasia in its rental fleet for many years and it’s the most popular boat in the fleet. It is equipped with two Sea-Cycle pedal drives, making the boat extremely maneuverable. With one drive pedaled forward and the other in reverse, it can spin around in its own length. The Sea Cycle drives are expensive, so for the Sanpram, Phil designed a drive for the do-it-yourselfer. Bicycle pedals and cranks turn large pulleys and V-belts transfer the power to a small pulley and an idler on the propeller shaft. The propeller is made of stacked plywood, like the one on his workbench.

Phil kept the tools he treasured most in a locked file cabinet. This is the first time the drawer has been opened since his passing. In the wooden box to the left is a proportional divider. To its right are two dial opisometers, or curvimeters, for measuring lengths long curved lines. I don’t know what the three devices with handles are. The black one to the right, made by Nikkor, has a lens that provides a fisheye view. The two with wooden handles are Phil’s home-made versions using wide-angle door viewers for lenses. The leather case at the bottom holds one of many slide rules.

I only knew what this was because I have one was passed down from my grandfather, a civil engineer. It’s a polar planimeter used to measure the area of shapes on a drawing. The top arm has a pin with a weighted disk to hold it in place. The other arm has a pointer that is used to trace the shape’s perimeter. The cylinder on the lower left has a polished steel wheel that both rolls and slides as the pointer moves. By some miracle, the area shows on the scale when the outline is complete. The planimeter can be used in boat design, for example, to measure the areas of hull cross sections.

This second model of the Aphasia was Phil’s most recent development of the design and did away with the expensive Sea-Cycle drives, adopting instead the DIY system of the Sanpram. I found the remains of two moths in the cockpit, the only passengers to ever get aboard the redesigned boat.

There are no markings in this half hull. Phil did some work designing commercial vessels and this may be one of them. It hangs in a room adjoining the shop, a windowless room lined with bookshelves.

Among the models in the shop is a steel passenger ship of unknown origin (Identified by a reader as the SS Tacoma. See Clayton Wright’s comments below.) and a freighter with a nesting barge. As I recall from my conversations with Phil, he designed the freighter while working as a naval architect. The idea was to create a system where cargo carried by two different means did not have to be reloaded. It’s like the freight trains that carry trailers or containers that are also hauled by truck or by ship. A barge used for inland waters could be floated aboard this purpose-built sea-going vessel.

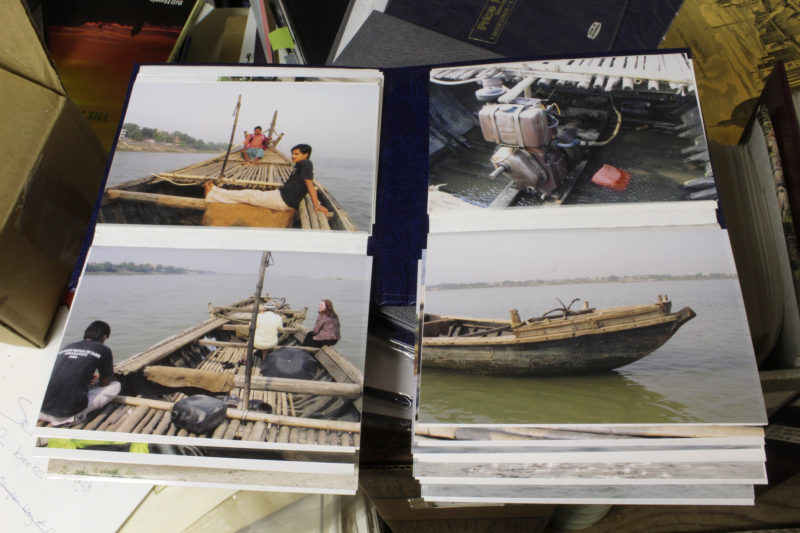

Phil did a lot of international travel and has bookshelves full of photo albums and file cabinets full of slides. His interest in boats of all kinds is evident in his photographs.

Hidden in the library was this painting. On the back is written in Phil’s hand: “Philip Thiel, late ’40s, early ’50s while student at M.I.T.” His oils were applied quite thickly, giving the painting rich texture. I knew he could draw well, but this was the first indication I’d had that Phil was, among everything else, a talented painter with an exceptional feel for color and free-flowing forms. It was a side of him that I discovered only after he was gone.

![]()

Thanks for this look at Phil’s life, Chris, as revealed by his shop.

I wish I’d known him.

Phil and your dad are smiling down on you. You think you are lucky to have known them…They’d say they are proud you were in their lives.

Really a nice trip down a smidgin of his life that left a long and happy legacy!

Nice indeed.

I admired Phil’s creativity and principled living. He swore-off automobiles I think in the 1960s and would only walk or bus around town. This meant you would run into him from time to time in the University District. Great guy who will be missed by anyone who spent a little time with him.

Excellent and extraordinary work, documenting such a wide genius’ mind in a short article, as was necessary. Perhaps a longer, more detailed biography should be in the works, and I would encourage it. I have a question on picture 5 from the top, that shows a couple of spray cans of Niagara, which is the same product I use to iron my shirts. It is, I believe, a sizing agent, like a starch (although Niagara also makes starch). What use would it have on the workshop, next to a lathe? I’m curious and interested to know.

Again, extraordinary mind, that of Phil Thiel’s, and I commend and thank you for your article.

Fernando Lopez-Evangelio, MHSA, Ph.D.

I wrote a profile about Phil for WoodenBoat (Issue #222, September/October 2011). There’s more information about his life there.

As for the spray cans, they are indeed Niagara spray starch—Original with the yellow cap and Heavy with the blue cap. Their placement next to the wood lathe may be one of those juxtapositions I mentioned.The laundry room is on the opposite side of the basement and the lathe isn’t on the way. Maybe Phil found a use for starch in the shop, maybe not.

As a long-time friend and admirer of Phil Thiel, I really appreciated your loving personal tour of his workshop.

He was an amazing and brilliant character, missed by many.

Thanks,

Marty

Looking through some other photos I took during a visit to Phil in 2011, I found this pop-up that he made of the Escargot.

A rich man, as I knew another. Thank you for a repast, as I needed it tonight

Thanks for the tour, and thanks to the family for sharing. Amazing creativity; that prop is incredible.

In our small-boat circle we are richly blessed by having men like Phil Thiel and you and many others, Chuck Leinweber, Marty Loken, Josh Colvin. Can’t name them all with us now and so many gone.

Thanks, Chris

I received a note from Tamiko Thiel, Phil’s first daughter, with some insights about some of the things I wrote about:

Most of the sayings in white chalk around the house, including the one I cited, are from Phil’s wife Midori. During dinner one evening she was telling a story, and Phil jumped up and wrote something on the mantle. Something Midori had said struck Phil as worth recording and it was the first thing he memorialized in chalk. Tamiko remembers it as “My nighttime is coming out in my daytime.”

Phil told Tamiko that he eyeballed the shape of first plywood propeller. He later wrote to an MIT professor who was an expert on propeller design, asking for his thoughts on a propeller suitable for human power with the boats he was developing. The professor entered the data in the sophisticated computer program he had created to calculate optimum propeller shapes. He sent the results to Phil and it was nearly an exact match for what he had come up through intuition and craftsmanship.

Tamiko recalls that as part of Phil’s research on perception of the environment, he spent a lot of time playing with fish-eye lenses as a way of capturing entire scenes. If he were still around, he would have been fascinated by the technology that now exists for 360° photos and videos. And seeing the photo of the barge-carrying freighter reminded Tamiko that Phil once mention he’d had a patent on the container-ship idea but it lapsed and someone else developed it into the system that now dominates goods shipments world-wide.

The photo album I included did not have pictures taken by Phil. While he did travel widely and take lots of photos, Tamiko took the shots shown here while on the Ganges River, near Patna in in state of Bihar, India. Phil asked for copies and wrote an article on the indigenous boats. She notes: “Now when I am traveling and see some boats with interesting shapes I take photos and then realize, with a sigh, that I have no one to send them to.”

I enjoyed your article immensely. Thank you for bringing some order and understanding to this very complex man with many and varied interests and expertise. Even before he became my graduate thesis advisor in 1980, which began our long association and friendship, he was much too intimidating a personality and intellect (your lead picture) for me to approach.

However, throwing my hands up at the available graduate design studios at the University of Washington (UW) on my return from my studies in Japan, I went to him as a last resort. It hardly seems necessary to say it, but choosing to work with Phil was the best decision I ever made and I continue to try to honor that every day.

The paper models are, of course, Phil’s work, but many of Phil’s very fine models were made by Gary Smoot, a very talented stage designer, product designer, and artist who was in one of Phil’s early Visual Awareness + Design undergraduate courses at UW, probably in ’82 or ’83. I’d guess the Aphasia and Sanpram models are all Gary’s work as he had a very special hand that Phil celebrated and Gary thoroughly enjoyed. Sadly, however, Gary died a year or so ago.

The viewers you found in the drawer had an important function in Phil’s course on Environmental Notation. I think the course was called “A Notation for the Built-Environment” or something like that. I took the course, of course, being his thesis student and had my own version of the ones you found. In the course there was a step-by-step procedure for their construction. They were used to develop and enclose or limit the visual field, which was carefully analyzed after being sketched. Phil liked to think of it as something like dance notation but not for the preservation aspect, rather it was a tool for sensitizing the visual perception of prospective designers. The “door peephole” on a screw eye and handle was the primary tool as it best approximated the human eye’s visual field for the purpose of Notation. The usefulness of the approximately 180-degree field of Nikkor fish-eye lens was questionable, but the optics were so appealing Phil couldn’t resist bringing it out to show its capabilities and, naturally, owning such a fine tool was an end in itself.

Thanks for the article, it got me thinking about Phil and missing him, but at the same time my life is so rich and full with memories precisely because of what he and I shared that the inevitable sadness that comes on me is, on balance, really nothing.

Well done, Chris!

I love APHASIA with the big prop and ergonomic seats. It would be great to try that modification some time. She’s still going strong, we’re going to be finally relaunching her this winter with Hobie Mirage Drives for propulsion.

I have been smitten by Phil Thiel’s Escargot, JoliBoat, and Friendship designs. Thank you for allowing me to see the man behind them. Fascinating look.

I was searching Phil Thiel when I came across your excellent reflection. I corresponded with Phil when I finished my own pedal-powered propeller boat in 2011 and sent him pictures. He responded enthusiastically with several letters and diagrams and offered good advice. I wanted to take the boat to Seattle to show him and meet the man, but I live in Spokane and didn’t get to it in time. A big regret.

The “steel passenger ship of unknown origin” in the third photo from the bottom is SS Tacoma, the fastest single-screw steamship in the world when launched in 1913. She was Puget Sound Navigation’s flagship and served the Seattle-Tacoma run exclusively, making four round trips per day. She remained flagship until 1935 when she lost that honor to Kalakala, for by then the automobile was becoming the primary mode of transportation and the mosquito fleet gave way to auto ferries.

I am currently building another pedal-propeller boat with heavy influences from Phil’s Sampram design.

Thanks for the article.

Clayton Wright

Thanks, Clayton, for identifying the model of SS TACOMA: 221′ long, 4-cylinder triple-expansion steam engine, 1000 passengers, 20+ knots. Scrapped in 1938. Phil collected dozens of books about steamships—and dozens more about steam locomotives—so it seems fitting that he’d have a model of a notable local steamship.

The planimeter was also used to measure the area of a card from a Crosby

Indicator rig to measure the H.P. of a steam reciprocating engine:

https://www.uh.edu/engines/epi2788.htm

Thanks for the article, Chris

Good morning!

I am interested in buying the construction plans of Phil Thiel’s Escargot.

You can purchase plans for the Escargot from the WoodenBoat Store. You may be interested in the Boat Profile we did in our April 2015 issue and a short cruise I wrote about in “Uncertain Ground” in our February 2018 issue.

Christopher Cunningham, editor, Small Boats Magazine

Are plans for sale for the smallest pedal boats, (1 person, belt driven), as shown in the original WoodenBoat story ?

Lets please keep the interest continuing!

For plans for the Sanpram, visit the Thiel web site, Sea/Land Design.

I emailed Phillip in late 2008 asking for ‘Friendship’ plans. He stated they were not done and I kept after him and finally he wrote me a wonderful friendly note and included the completed plans. Wonderful man. Wonderful boat.