I’ve long been fascinated by the ancient square rig. It has been widely acclaimed for its downwind and reaching ability, but the traditional sails were often poor working upwind and required extensive rigging to do so. I wanted to experience what it was like to use the rig, and also to improve on its effectiveness using modern materials and aerodynamic theory. I built several square rigs for canoes and my peapod, and those results were rewarding.

Bob Cavenagh

Bob CavenaghMike moved his weight aft to steer downwind. A bit of belly or camber in the sail increases its stability, so he has pulled it up against the mast and the clews farther astern, curving the fiberglass batten sewn into the foot.

One simple sail for my canoe was particularly instructive. I made it quickly, just a flat shower curtain with edge reinforcements and a fiberglass bicycle flagpole for a batten, slipped into a sleeve sewn in its foot. It would go downwind and broad-reach as well as the traditional rig’s reputation suggested. My friend Mike tried it out on his beautiful 1937 Peterborough canoe with only a paddle and boat trim for steering.

Downwind, these sails do best when they have some “belly” to contain the wind and minimize eddies curling around, destructively, to the front of the sail. We achieved this by pulling the battened foot of the sail up against the mast, then creating the belly by pulling the sheets further to the rear. We also found that we could pull one corner of the sail snug against the mast, and downward; when we did so the sail could be pulled fore-and-aft and would point higher.

Bob Cavenagh

Bob CavenaghMike moved forward to depress the bow and steer closer to the wind, and he has pulled the leading edge of the sail down and fairly taut. The batten in the foot maintains the shape of the sail. In this mode he can sail downwind through about 150 degrees with only a paddle for steering and lateral plane. The sail now functions as a standing lug. On my sailing canoe with leeboard and rudder,that angle increases to over 180 degrees, depending on wind strength. A more refined sail with a strong downhaul could prove even better.

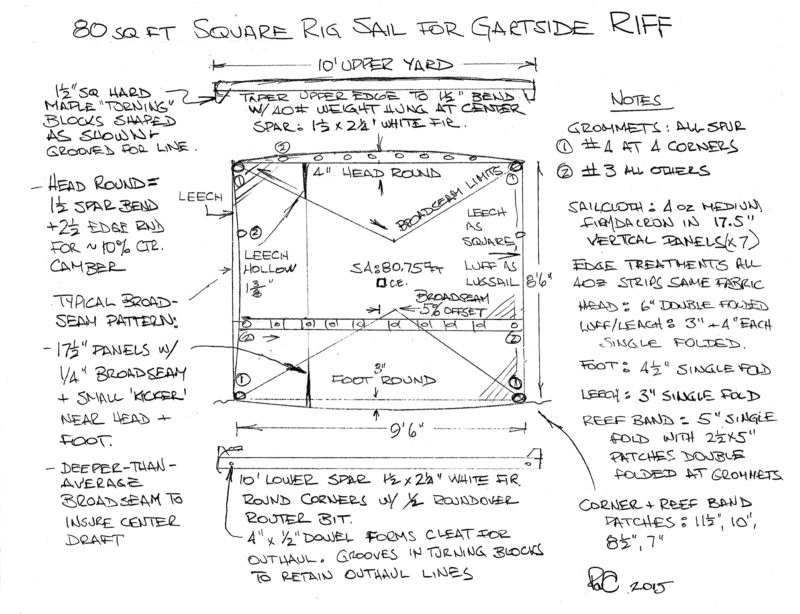

Encouraged, I later built a bigger, carefully designed sail rig for my Gartside Riff catboat, ROSE. I used 4-oz Dacron sailcloth and gave it a lower spar to tension its foot, avoiding the complex rigging of historic ships. ROSE’s unstayed mast lets the sail rotate easily without being hindered by shrouds and stays. This sail is a rectangle slightly wider than it is tall. (Square rig sails came in many shapes and were only occasionally square; the name comes from the sail being hung perpendicular—square—to the mast.) I designed this sail as I would a contemporary balanced lug, with a loose foot, vertical panels, head and foot round, and broad-seamed to make the middle fuller than the top and bottom. The starboard edge is perfectly straight and built to withstand high tension while serving as a lugsail’s luff, while the port edge is hollowed a tiny bit to prevent it stretching and flapping when it’s serving as a lugsail’s leech. I also moved the deepest draft from center to 5 percent toward the starboard edge to give better control in fore-and-aft mode. The loose foot can be tightened for upwind work and loosened for downwind, creating the desired belly. When loosened, the effective center of effort moves back toward the middle of the sail.

drawing by the author

drawing by the author.

The sail operates in two distinctive modes: across and down wind, with the yard square to the mast, and upwind, with the sail hauled fore-and aft. Going downwind in the square mode, the sail is docile and easy to handle. In the upwind mode, the rig can also work across and downwind, but downwind steering is, as you’d expect of a sail set well outboard to one side of the hull, much more demanding of the skipper.

Chuck Laudermilch

Chuck LaudermilchReaching in a wind blowing at about 12 mph, with whitecaps beginning to form, it will soon be time to reef. The upper yard is suspended from a pair of ‘lifts’ that spread load on the spar and also raise the pivot point. The downhaul next to the mast can tension the lower spar as needed and transfers sail thrust to the hull, reducing strain on the pair of sheets attached to the lower corners.

A 4:1 downhaul is attached to the center of the lower spar for the square-sail mode, or near the starboard/front edge for lug-sail mode. Either way, this allows the edges to be tensioned, which is essential as it lets the sail develop aerodynamic lift and point higher. The leading-edge tension in fore-and-aft mode is much higher, creating the taut luff that is the key to best upwind performance.

Chuck Laudermilch

Chuck LaudermilchHeaded upwind in lug mode.

In square mode I can run and beam-reach through a downwind arc of 190 degrees and more. When I take a couple of minutes to change mode to fore-and-aft, I move the downhaul point and change the sheets. The sail is now rigged like a balanced lug, and in this mode I can tack reliably and point as close as 55 compass degrees to the wind. Not too bad for a lugsail, let alone a square sail! With almost 30 percent of the sail forward of the mast in lug mode, one must tack rather decisively to keep from being backwinded, and this takes a bit of practice.

Bob Cavenagh

Bob CavenaghThe lifts have allowed the center of effort of the sail to move rearward, matching that of the designers lug sail. The downwind sheets are disconnected, the downhaul moved to near the front of the spar, and a 4:1 mainsheet attached to the spar. The diagonal creases— called girts—will disappear in stronger winds.

I am quite satisfied with my new sail. It performs better upwind than I expected, given its low aspect ratio. The current rigging gets the job done, but there remains room for new thinking on the arrangements: I’d like to make the transition between modes quicker and easier to do without going forward.

My experiments with square rigs have satisfied my curiosity and exceeded my expectations. I think this sort of contemporary square rig has good potential for sailing courses that include lots of downwind work, for which square format is quite docile. When higher reaching and upwind work is called for, it can be changed to the lug mode. Lugsails appear to be the heirs apparent to the square rig, and this two-mode setup gave me a glimpse at the how and why.![]()

Bob Cavenagh grew up in a Navy family and lived in seaports and around ships and boats from infancy. At the age of five he built his first boat; it sank immediately. After college, Army, and grad school he began an academic career, bought his first sailboat and canoe in 1975, and has been an enthusiastic sailor ever since. For the last three decades he has pursued a particular interest in rigs and sailmaking. Now retired, he spends summers sailing a small fleet of small boats on a Canadian lake.

You can share your tricks of the trade with other Small Boats Monthly readers by sending us an email.

Lovely idea, sailing down the lake with a shower curtain. I was just thinking of making my own lug sail for my Oughtred Sea Hen and this helps a great deal. Thanks.

Thanks for this, Bob. I have been sailing a bit in a lug-rigged ketch and reading Spritsails and Lugsails by John Leather and have a mind to experiment myself. Your article and drawing are very interesting and timely. I wonder if you could have reefed it down enough to sail in St. Michaels today!

(Editor’s note: Bob would have enjoyed attending the Mid-Atlantic Small Craft Festival at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michaels this weekend, but the event was cancelled as the approach of Hurricane Joaquin brought high winds. At the time of writing, Friday afternoon, the museum’s phone lines are down and heavy rains have put the St. Michaels area on a flood watch.)

Very interesting article, Bob. I am presently building a 14’6″ Viking vessel and have been looking for the perfect looking sail. My first inclination was to develop a balanced lug sail If you get a chance take a look at my blog and tell me what you would do.

That is a nice looking, fascinating and substantial project. In addition to the weighted shallow keel you have added a centerboard. That could help working to windward and reaching, but I haven’t figured out the relative mast location, which will be important. The square sprit sail in the Swedish plan looks right, but since you want a Viking look, that would suggest a square rig perhaps twice as wide as the hull. Unfortunately that would be a low aspect sail and subject to drag when sailing upwind. A more moderate square rig, similar to the one I used for ROSE-the-Riff could work pretty well, since it can convert to a lug format and perhaps work better upwind. At a guess, I’d think you could use 80-100 square feet of sail.

A problem with scaling a Viking longship down is that everything can be reduced in size except the crew, and sheet leads thus can become difficult. I’ll bet you have watched the video, “Sailing the Test Boats for Draken Harald Hårfagre.” If not, do, and watch the performance of flatter and fatter sails on different points.

Bob,

The square that I have on my Afjordsfaering is pretty high-aspect ratio. The yard is barely wider than the boat. And the larger 19th-century Norse boats have the same kind of rig. I wonder how that evolved. Mine, of course, has the bowline that runs to the stem and a sail stick onto which the sheet and tack is made fast. This rigging does require two people to sail the boat. It might be interesting to rig a boom for it and see what it does when sailed lug-like.

Hello Ben. The boom proved to be a real game changer. With a modern 4:1 tackle to tension the leading edge, upwind behavior became very gratifying. Downwind, the tackle relieves much of the pressure on the sheets, but as noted below it does require some attention in a sudden gust. With your larger hull, you could probably drop the boom for strictly downwind work.

My sail is cut to perform as a lug.

Does the high-aspect ration require braces to the head of your sail? I am working up a higher aspect sail to try on my tin canoe at Cedar Key in March.

Innovative as ever, Bob, and what lovely testing ground. You’ve gone a far fetch further than the Norse: It appears they reefed by twisting the two clews together to reduce sail.

Just to prove that Bob channels the wisdom of the ancients, I submit this article about a square rig for canoes from 110+ years ago. The author, E.T.Keyser, used stock Rushton canoe hardware but most interesting is the way the mast is added and supported. I’d actually run the mast tackle shown in the article a little differently to get at least a 2:1 advantage.

That is another classically beautiful Cheap Pages reproduction, Craig. I read it 2-3 times while working up the project. Thanks!

Fascinating. I hadn’t guessed that a square sail could be that versatile.

Bob, very interesting, thank you. I like the idea of the off-the-wind square rig, but I puzzled: How do you de-power quickly? With a lug rig, or indeed any asymmetric, unstayed rig, you can just let go of the mainsheet. But with equal pressure of the wind on both sides of the sail, I presume this doesn’t work?

There are different solutions for the two sails. The foot of the “tanbark” canoe sail is held only by the two sheets, so when headed downwind you can ease both to let the sail rise and spill air or make the faster and more radical solution: letting go of one sheet and hauling the other aft. These options quickly become instinctive.

Since the big sail on Rose is tethered to the deck by the downhaul you can release and ease the downhaul, again letting the sail rise. With a 4:1 tackle involved, that may take too long in a violent gust, in which case you release one sheet and haul the other aft rather smartly, spilling air. At that point you can either drop the sail, tie in a reef, or, gust past, you can power it up again.

Of course, in lug modes, you treat either sail like any other lug.

Thanks, I think I’ll avoid a central downhaul in that case!

I’m playing with the idea of a boomless square sail that can switch on the fly from square to a dipping lug for my Clint Chase Drake. I’d have a double sheet in each lower corner. One would be a conventional sheet, the other would run forward to a ring on the gunwale, and back to my hands: hauling on this would bring the forward corner of the sail to the gunwale, and in doing so tilt the yard from horizontal. (I think that would make that ‘sheet’ a ‘tack-line’?). I might put a cam cleat to hold the tack line. I think the ‘double sheet’ would work best as a continuous loop: tack line from the corner of the sail, through the ring on gunwale, back to hands, plenty of slack and then the same line goes back to the corner of the sail as the sheet. There’d need to be enough slack to let the sail fly if one let go.

This would create a shape and set up similar to a dipping lug, which would presumably be pretty powerful across the wind. To jibe, I’d slacken off the tack line while pulling on the other sheet, this would put the sail at right angles to the centerline, then continuing to pull would put the sail back in the dipped position on the other ‘tack’.

I still need to measure things up and see if this might work outside of my head! I imagine this set up would work best as a truncated pyramid rather than actually a square.

I can’t imagine I’m the first person to think of this?

By all means give it a try. You will be approximating the “bowlines” used on historic square rigs—lines from the luff of the sail to points forward. This will indeed approximate a dipping lug.

The article describes just two of the square-rig variations I have tried. If you scroll back up to the second canoe picture, you will see the sail functioning as a standing lug. In one variation, I placed a dowel through the mast a bit below the tack location in the picture. I could then hook the forward sheet under it (using a paddle), pull the tack down strongly, and thus improve upwind performance.

You don’t mention using a lower spar. That spar on ROSE is the key to achieving windward performance, as my downhaul can tension it anywhere from the middle of the spar (for downwind) to near the tack, achieving the luff tension needed for upwind work. That spar also lets me control the shape of the foot of the sail. Without it, it can be hard to flatten the sail aft. The sheet tension on the small canoe sail can be quite high. The downhaul transfers much of the thrust of the lower half of the sail to the hull.

I don’t find the gradual and urgent techniques to spill air from the sail to be onerous.

Bob

Thanks a lot for sharing an excellent development. I’m presently working on my own design of 42′ sail boat. I would love to apply your idea plus some roiling reefing solution. Similar like in Paradox boat. I would appreciate any comments.

Best of luck with the project. I’ve been intrigued by Matt Leyden’s hull and rig designs. The latter reminds me of some older Vietnamese rigs (see the Junk Blue Book, with a more primitive roller arrangement.

I am not sure how well those rigs go to weather. In some ways they seem similar to crab claw sails, but without the tapered point at the tack.

My next square rig will be for a canoe, and it will have higher aspect ratio.

Bob