After the close of the American Civil War in 1865, John Wesley Powell, a Union Army veteran who had lost his right forearm to a Confederate musket ball, returned to civilian life as a geology professor. In 1869, he set out to explore and survey the Green and Colorado Rivers and lead the first scientific expedition through the entire Grand Canyon. The feat required boats built specifically for the task by the Thomas Bagley boatyard in Chicago. In the 1860s, there were no boats appropriate for this kind of journey and also no practical way to get them there until the completion of the first Transcontinental Railroad on May 10, 1869. Bagley could then send the boats west by rail to the Green River station in Wyoming. After christening the three large boats KITTY CLYDE’S SISTER, MAID OF THE CAÑON, NO NAME, and the small one EMMA DEAN, the expedition got underway on May 24, 1869. Three months later, on August 30, Powell arrived at his goal, the mouth of the Virgin River, with just three of his four boats and six of the ten men he’d set out with.

In 2013, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) commissioned the Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding to recreate two of Bagley’s 21′ Whitehall “freight boats” and the smaller 16′ scout boat for Operation Grand Canyon, a TV program about the retracing the famous expedition by Powell, who was later the director of the U.S. Geological Survey. I worked with eight students to build the Whitehalls, and senior instructor Jeff Hammond built the scout boat with other students.

There are no plans or pictures of the boats of this expedition. Powell’s journals offer only an outline for their construction:

Three* are built of oak; stanch [sic] and firm; doubled-ribbed with double stem and stern posts, and further strengthened by bulkheads, dividing each into three compartments.

Two of these, fore and aft, are decked, forming water-tight cabins. It is expected these will buoy the boats should the waves roll over them in rough water. The little vessels are twenty-one feet long and, taking out the cargoes, can be carried by four men.

The fourth boat is made of pine, very light, but sixteen feet in length, with a sharp cutwater, and every way built for fast rowing and divided into compartments as the others.

*One of Powell’s boats was lost at the rapids he named Disaster Falls. For Operation Grand Canyon only the boats that had survived were replicated.

The usual carvel construction of Whitehalls in the last half of the 19th century was ill-suited for this type of expedition, and, following Powell’s notes and channeling Thomas Bagley, I beefed everything up considerably and added some atypical features. I decided that Bagley would have added a keel batten to back up the garboards if he was concerned about the boat coming down hard on a rock. I also studied photographs and engravings in books about Powell’s second expedition—in 1871—and built the boats the way I felt Bagley would have in 1869.

Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding

Northwest School of Wooden BoatbuildingThe oak logs harvested for the Whitehalls were sawn with a bandsaw mill in Bristol, Rhode Island. The planks cut from trees with curved trunks made it possible to get planks with a lot of shape out in one piece.

The first two tasks were to find suitable white oak and to draw the lines that would later be lofted full size. While Jeff and I were drawing lines, our executive director at the time, Pete Leenhouts, was on the phone searching for oak. He eventually found white oak big enough for full-length planks and backbone timbers in Rhode Island, some 3,000 miles away. While we were building the strongback and making patterns and molds, the oak was being harvested and sawn and I was quite nervous about building boats with green wood.

The oak arrived, some as rough-sawn 10/4 flitches. We planed them down to 2 ¼″ and arranged our Mylar backbone patterns to make the best use of the oak’s beautiful grain. The wood had had very little time to dry after being cut, and our moisture meter just blinked—the readings were off the charts.

Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding

Northwest School of Wooden BoatbuildingThe frames on the two large Whitehalls would soon be bent around the forms’ ribbands. Pockets chopped in the backbone aft (left) allowed the frames to get a nice tuck in the stern. Whitehall designs vary slightly depending on the builder; I drew these boats with the aid of lines from John Gardner’s Building Classic Small Craft and lines taken from a San Francisco Whitehall by fellow instructor Jack Becker.

My students seemed to be enjoying themselves despite the cold, wet, dark shelter we worked in and our morale was high. Soon enough the enormous backbone was in place, and the transom was bolted on.

Powell’s description of the boats as “doubled-ribbed” could be taken to mean either that there were twice as many frames as a normal Whitehall might have or that each was twice as thick. I decided to compromise by increasing the thickness by half and decreasing the normal frame spacing from 9″ to 6″.

Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding

Northwest School of Wooden BoatbuildingAs we decked the large oak boats the plank seams began opening up. If you look closely at the seam just below the forward thwart you’ll see light coming through. The hatches were made traditionally without any modern gasket materials. Water found its way into the “sealed” compartments in a few big rapids making it difficult to keep gear dry. Powell must have dealt with the same problem.

The green oak was glorious to bend when steamed—it could take a 90-degree twist in a matter of a few feet—so the garboards went on quickly and we had plenty of time to put on the first broadstrake before we left for the weekend. On Monday morning, as I’d feared, the plank seams that were perfect on Friday now had ¼″ gaps. It was going to be a battle to get these boats to float. I tried everything I knew to keep this from happening again—oiling the planks to slow the drying, building a kiln to dry the oak before it went on the boat, even using a wood stabilizer that replaces water in the cells—but in the end it was a losing battle. Time was not our ally, so we planked the boats and let the oak do what it wanted to do. We flipped the hulls and turned to fitting out the interior and decks.

Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding

Northwest School of Wooden BoatbuildingPete Leenhouts, then the school’s director, and author Ben Kahn contemplate the widening gaps in the planking seams and the looming deadline for the completion of the boats.

By May, it was time to get the boats afloat, but some of the seams had gaps of as much as 3/8″. We ripped 8′ lengths of red-cedar splines, matched to the thickness of our planks. Because the seam gaps were anything but uniform, we made splines in several different widths, coated them with linseed oil, and tapped them in. The cotton caulking that followed kept everything in place without glue. I had to leave the shop in disgust several times after I’d caulked the same spot multiple times before it seated properly and didn’t blow out the inside of the planks. My students were calmer than I was about the whole process and so absorbed in it that they wouldn’t even look up when I blurted out my frustrations.

Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding

Northwest School of Wooden BoatbuildingThe scout boat’s tongue-and-groove decking will have tarred felt stretched over it, followed by canvas and paint. A few of the screws here await bungs. The scout boat had bronze screws and the large boats had galvanized screws; Powell’s journals didn’t mention the type of fasteners used in his boats.

After six months of work we put the Whitehalls—one painted green, the other blue—and the red-hulled scout boat on the beach by the school and waited for the rising tide to lift them off their slings. In the days that followed I trained with the boats in the bay. They were like huge battleships compared to the light boats I was used to rowing, but they could take a pounding like no other Whitehall. They were ready for their journey.

Bryan Smith

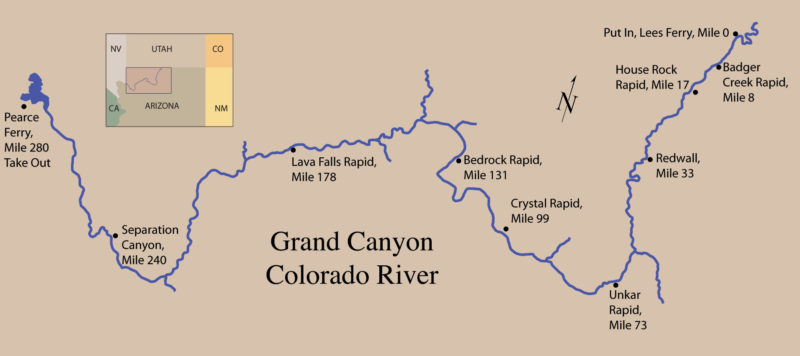

Bryan SmithThe two Whitehalls, left and center, and the scout boat, right, lined up at Redwall ready for action. Powell came ashore here on August 8, 1869 and named the place for a 400′ band of cliffs stained red by iron leaching from the strata above them.

The boats arrived in Flagstaff, Arizona, amidst such a frenzy of activity and preparations for the trip down the Colorado that they were never given names. Fred Thevanin, the fearless leader of Arizona Raft Adventures (AZRA) and in charge of the trip, also served as the guide in the scout boat I’d be in as crew. I had never seen such insanity as people threw bags of potatoes, welded solar-panel brackets onto raft frames, filled whiskey barrels, and moved boats around. We were all as excited and as anxious as we’d have been if we were going to the moon and might never come back. Even the guides, who had been down this stretch of river countless times, knew this would be no ordinary trip.

A few days before launching, the British boatmen arrived along with the remaining film crew—which included Dan Snow, a popular British television host and dedicated historian. The boat crew included Mike Dilger, an ecologist and BBC reporter; Dougal Jerram, a geologist; Sam Willis a maritime historian; Bryan Smith, a filmmaker and whitewater kayaker; Fred Thevanin; and Adam Bringhurst and Tom O’Hara, both river guides. This crew of nine was the same number Powell had for this stretch.

We piled everything into trucks and headed to the boat ramp at Lees Ferry, arriving to ominous claps of thunder and bright, ragged lightning bolts. The rain came soon after so we checked into a local hotel for one last comfortable sleep. Those who hadn’t been down the river looked to the guides for assurance, but because they had never used boats like those we’d built even they were unsure.

Bryan Smith

Bryan SmithThe scout boat, with only 6′ of cockpit between its bulkheads, was cramped for our crew of three but on the bright side, with just the one rowing station, Sam and I each had to row only half much as the crew in the other boats and had only half as much water to bail when we got swamped.

The next day, we launched the boats for rowing trials. The hulls had dried out in the desert air, and the seams were leaking badly. I assured everyone that this was normal and the planks would swell up, but feeling cold water around my shins as I rowed a sinking boat made me more terrified by the hour. I had committed to something that now seemed downright foolish; once we left Lees Ferry, there would be no getting out of the canyon except by helicopter. I took solace from Tom’s calm demeanor and focused energy. As we shoved off and headed downstream, I took a deep breath, rejected negative thoughts, and pondered the eight months of hard work that had gotten me this far. What a relief it was to be on the river, living in the moment, and no longer fearing the future. As we rowed through the first riffle, I was surprised by our speed; Fred was quickly figuring out how to manage the 14′ ash sweep he was using to steer. After that riffle, my anxiety turned to excitement.

Bryan Smith

Bryan SmithFred set the scout boat up for the line he’d chosen to run Badger Creek Rapid.

Our first real challenge was 17 miles downriver from Lees Ferry at House Rock Rapid, where the current threatens to take you into a large hydraulic hole to the left; to avoid it, the boat must cross the river mid-rapid and dodge huge rocks on the river’s right. It would test our maneuverability. As we dropped into the smooth V of water at the top of the rapid, Fred said, “Take me on a walk,” meaning row with a slow but powerful cadence. When smooth water turned to cresting waves Fred said: “Take me on a jog.” A cold breaking wave smacked me in the back and took my breath away. Another wave wrapped around us from the other side. “Don’t forget to breathe,” Fred yelled. He squared up the bow of the boat with the huge lateral wave. As the boat climbed, the water pushed our bow parallel to the lip on top of the wave and we got a glimpse over the edge into the deep and deadly hole, which was roaring like a jet engine. Then, like a big-wave surfer, our boat dropped into the downstream trough, sped into flat water, and pushed through the eddy line with authority. As the eddy spun the boat up river, we were nearly submerged and bailed water while our hearts pounded. The other two boats punch though the waves and into the safety of the eddy.

That night, we camped on a soft, sandy beach sloping from a sheer wall of ancient rocks. Everyone had aches and pains, even the film crew. Despite being on modern rafts, they too had taken some punishment. We unloaded the boats of gear and food, and set up the kitchen. Fred and Bryan figured out what to make for dinner. Our meals consisted of foods that Powell may have taken on his journey. By this point on Powell’s trip, his crew had been on the river for months and were running out of food. Our meal was simple but delicious after a long day of physical exertion under the desert sun.

Bryan Smith

Bryan SmithWe set up camp on a beautiful beach above Unkar Rapid. Unkar is the Paiute word for red stone; the area has several archaeological sites, indications of a settlement dating back 1,000 years.

On many of the nights that followed, like our first night camping just upstream from the head of Crystal Rapid, we would drink bottom-shelf whiskey and sing around the campfire to the beautiful music of Sam and Tom on guitar and banjo. On those nights when we expected torrential rains, I’d work with the English crewmembers to create shelters out of a huge canvas tarp using oars as poles. At the camp downstream from Separation Canyon, we set up a particularly nice canopy over the kitchen using four oars on the perimeter and a longer sweep oar for the peak. We were grown men arguing the finer details of design and knots while wrestling a huge leaky tarp, but it felt like we were kids building a fort.

Bryan Smith

Bryan SmithOn a sweltering off-river day, I got a chance to put a riser block under the scout boat’s stern-sweep oarlock. Fred needed a few extra inches above the deck to get his sweep oar to clear cresting waves.

The boats were constantly deteriorating, and I spent most evenings fixing broken oarlocks, patching holes, and mending oars. To achieve better trim for steering and climbing over waves, I arranged a few boulders as ballast in the stern compartments. Obsessed with the maintenance of the boats we’d created, I was prepared and ready for almost any repair. I’d brought wood, screws, bolts, and three canvas bags full of tools. Almost daily something needed to be fixed. Halfway through the canyon, CRAZY HORSE, as Dan had been calling the blue boat, pulled through an eddy line and struck a rock concealed just below the surface of the water; an hour later, as the fleet pulled into camp, Dan mentioned the boat was sinking. The mangled stem and keel took three hours to fix, with three other team members helping. I had brought large pieces of wood to replace broken pieces, but even if we could replace the stem and keel, the task would have set us back a week. So we put tar in and around the hole, molded a lead sheet by hammering it over the tar, and then tacked it down with copper nails. The four of us showed up for dinner covered with splattered tar.

Bryan Smith

Bryan SmithAdam drilled holes in the oarlocks to attach tethers. Our sweep oars had been getting wrenched out by powerful whitewater and these simple modifications successfully kept the oars and their oarlocks from getting lost overboard.

It was satisfying to see what these boats could endure. People asked me if it was painful to watch the boats get damaged over and over again, but I enjoyed seeing them pushed to their limits and beyond and relished the challenge of keeping them afloat. CRAZY HORSE collided with a sheer wall at Bed Rock Rapid and I was amazed the boat didn’t break in two. The patch we’d put on a few days earlier was ripped completely off, exposing the hole again. The impact punched through the planks, but the damage could have been much worse: The double framing prevented more of the plank from being shattered, and the hole in the stem could be repaired because the timber was oversized.

Bryan Smith

Bryan SmithDan and Dougal kept CRAZY HORSE moving slightly faster than the current so Tom could maneuver the boat and navigate around flat-water obstacles.

Crystal Rapid was an exceptional threat to both boats and crew. The filmmakers wanted us to line one boat, portage the second boat, and run the rapid with the third boat to demonstrate methods used by Powell’s expedition. We eased CRAZY HORSE down the bank next to the rapid, with Tom and Bryan in the boat and the rest of us three-deep paying out and then grasping bow and stern lines, we controlled the boat’s descent. We let the boat drift just far enough from shore for the current to pull it downstream without letting it into faster-moving water that would have ripped the lines out of our hands. At one point, CRAZY HORSE perched on some rocks and rolled on its side, allowing a huge wave to come over the rail. The additional weight solidly pinned the boat there, and despite trying for hours we could not free it. We gave up, hoping that the expected decrease in water level at night (the Glen Canyon dam upstream releases less water as the demand for electricity diminishes in the evening) would help get it off the rocks. It was depressing to think that the boat might be in its final resting place. If three crew were rendered boatless, they would have to cram aboard the other two boats. At 4 a.m., however, the water was low enough that we could bail the boat and work it free, after which we lined it the rest of the way to a beach at the bottom of the rapid.

We portaged the scout boat around Crystal Rapid. All nine of us carried provisions and gear 400 yards downriver along the bank. We then lashed oars across the 800-lb boat to provide handholds for carrying it over boulders at the edge of the river. Stumbling and falling in the sweltering sun, it took us hours to portage the boat.

The green boat ran Crystal Rapid and got swept into a boulder garden, slamming into several rocks without much damage. While Powell portaged his boats overland to avoid rapids he deemed unwise to run, most of us agreed that running the rapid was the best way to get people and boats down the river. It was less risky for the boats than lining and safer for the crew than portaging.

Bryan Smith

Bryan SmithAdam, Bryan, and Mike braced for a big hit at Lava Falls. Moments later, their boat disappeared into a hole and resurfaced with only Bryan and Mike still aboard.

Lava Falls was our last big rapid. Of all of the rapids in the Grand Canyon, it is widely regarded as the most powerful and the most dangerous. The film crew took several hours to set up, since they would have only one chance to capture the run on film. After hours of watching private groups scout the rapid only to have Lava Falls flip their rafts, it was finally our turn.

I shoved off while Fred gave directions to Sam on the oars. Fred maneuvered the boat a few feet to the right of a giant hole that has claimed many boats over the years. The muddy water was boiling as we plowed through and over a train of giant waves. At the bottom of the rapid we rode over a pressure wave the size of a bus and came to rest in an eddy on the right side.

Bryan Smith

Bryan SmithAlthough it looks like we’re about to be swallowed up by the whitewater, Fred had chosen a perfect line to get the scout boat safely through the heart of Lava Falls.

Next came CRAZY HORSE carrying Tom, Dan, and Dougal, who also survived Lava even though the boat was swamped. We all stood by as Adam, Bryan, and Mike entered the rapid in their Whitehall. Adam maneuvered next to the explosive keeper hole at the top, then his boat hit a huge hole at the bottom and vanished. When it emerged from the depths like a breaching whale, only two people were aboard. Adam was gone. We quickly rowed out in search of him. Adam eventually resurfaced 10′ behind his boat and swam to catch up. With Bryan’s help, he clambered aboard just before they were swept into the next rapid, Son of Lava. Completely swamped and lacking Adam’s steering sweep, they were at the mercy of the river; they could only hope for the best. All three boats made it through. Our nerves shattered, we regrouped, had a quick bite to eat, and rowed in silence for an hour until we reached our next camp.

Bryan Smith

Bryan SmithOur last day in the canyon we ate breakfast in the dark and pushed off the beach at daybreak. We rowed through a thick low-lying fog and covered our last miles on flat water. All the drama was behind us.

Our 18 days in the Grand Canyon gave us a deeper understanding of ourselves, the power of the great Colorado River, and the toughness of Powell and his crew. Only six of the 10 who started his 101-day, 930-mile expedition made it through the canyon, the final leg of the journey. One had given up before reaching the Grand Canyon and after Lava Falls three of the men abandoned Powell at Separation Canyon and were never seen again. Of his four boats, three made it to the end of the expedition. After running just the 280 miles of the canyon and more than 100 rapids, I understood all too clearly my obligation as a boatbuilder to build boats as best I can and to take good care of them. In the Grand Canyon the bond created with boats is especially strong; as the Colorado River guides say: “If you want to live, stay with your boat.”![]()

Ben Kahn earned a bachelor’s degree in industrial arts from Berea College in Kentucky in 1999 and graduated from the Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding (NWSWB) in 2001. Working in the Port Townsend, Washington, and Sausalito, California, shipyards prepared him for his current job teaching at NWSWB. He spends his free time enjoying boats and friends in the beautiful Pacific Northwest.

A trailer for the Operation Grand Canyon, is on the BBC’s YouTube channel.

A footnote

John Wesley Powell went on to serve as the director of the U.S. Geological Survey, and as an anthropologist and ethnographer he was the first director of ethnology at the Smithsonian Institution. He died, strangely enough, in 1902 in none other than Brooklin, Maine—the headquarters of Small Boats Monthly and its sister publication, WoodenBoat. For more about his explorations, see Wallace Stenger’s book Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Did you consider lapstrake planking? Seems it would have helped with the wood movement as it dried out, and would provide stronger resistance to impacts. Of course, repairing lapstrake planking is more of a challenge.

Plywood dories were tried out on the Colorado some years ago (as reported in WoodenBoat), and proved to be quite successful. A bit of rocker in the bottom makes them a lot more maneuverable. The evolution of the dory for river work has led to the Mackenzie River dory, quite popular with salmon fishermen around here (the Pacific Northwest) on the various streams. They have a lot of rocker on the bottom, and an extremely springy sheer.

Having rafted the Grand Canyon many years ago I really identified with the author as he described the rapids. Great story and the boats were wonderful too.

I strongly recommend reading Down the Great Unknown by Edward Dolnick, the former chief science writer for the Boston Globe. The book is as authoritative as is possible for such an event. It is detailed but deeply gripping. It includes maps and a large number of illustrations and photos. The author clearly outlines how horribly unsuited Powell’s boats were and the immense effort exerted by the crew just to survive. (published by Harper Collins, 2002, ISBN 0 00 653223 3)