The Waterlust sailing canoe designed by Dillon Majoros of Chesapeake Light Craft (CLC) is a 17′ decked sailing canoe designed for “high-performance expedition cruising.” It was developed in 2016 in partnership with Waterlust, a group of environmentally focused scientists, for a journey along the Intracoastal Waterway. It has a choice of rigs, and the option of a Hobie MirageDrive for auxiliary power.

I fell in love with the graceful sheer and reasoned that the boat was not so big, and I would not have invested too much time, money, and energy if I found out that either I was not the boatbuilder I had hoped I might be, or that the boat was not right for me. The boat did turn out to be the right one, and the sheer still gets me every time.

The boat is available as either kit or plans from CLC or their partners around the globe, as part of their Pro-Kits range, which is aimed at people who have some degree of competence with epoxy-plywood construction. I sourced my kit and instruction booklet from Fyne Boat Kits in the U.K. The kit contained precut plywood parts, resin, ’glass, and most of the hardwood required machined to the right dimensions, with precut puzzle joints—just what a builder needs to make rapid progress. Sails and hardware can also be provided, although I sourced mine elsewhere. This was my first build, but it went together very easily, and the 28-page instruction booklet is well illustrated, clear, and easy to follow. The few questions that I had were quickly addressed either by Fyne or CLC.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThe cockpit extends beneath the aft deck and can be used as a berth for the crew. Forward of the centerboard built-in compartments to both port and starboard give accessible, dry stowage space, and in the canoe’s ends watertight compartments provide excellent flotation.

The construction is typical for a modern kit boat, with hull planks and frames being stitched together, then bonded with thickened epoxy, and the resulting structure reinforced with ’glass cloth. I was astonished by the precision of the cutting—all the predrilled holes for the stitches lined up perfectly, and the LapStitch hull came together quickly and easily. My kit arrived in early March 2020, and the hull was ready to launch in late May.

Even during the build, it became apparent that the Waterlust is a substantial canoe. With a beam of 36″ and full ends, the hull’s load-carrying potential becomes clear as soon as the last planks are stitched to the bulkheads.

There is a watertight compartment built into each end, and forward of the cockpit is a large storage locker accessed through a watertight hatch cut out from the deck. The deck is supported by a combination of the plywood frames, bulkheads, and carlins. I added two additional deckbeams fore and aft of the hatch opening, strengthening this area to support sitting on the deck.

In the forward part of the cockpit is the slot for the daggerboard, and the well for the drop-in MirageDrive. We opted to use paddles for auxiliary power and to use the well, with the hull left intact at the bottom, as an additional storage locker. The main cockpit area is large and divided by the longitudinal stringers that provide strength to the hull. The spaces to the outside of the stringers provide convenient open-top storage areas and keep loose items handy but out from underfoot. Between the stringers, the center cockpit space extends unimpeded under the aft deck, creating a 35″-long space for more storage. As this is open to the cockpit there is more chance things stored here will get wet, so I use dry bags or sealed plastic boxes in this space; when cleared, it is large enough for sleeping. I have not tried sleeping on board but know others who have with success.

The amas increase the canoe’s buoyancy by 70 lbs on each side and offer yet more options: on windy days the canoe can be sailed with full rig, while on less windy but gusty days they provide stability for a more relaxing sail. A single-blade paddle is useful auxiliary power in a difficult turn or very light airs.

A suggested hardware layout is provided in the construction manual, and I used this with minor modifications. My spars are all solid wood, as suggested in the plans. A hollow mainmast may be advantageous to reduce weight aloft, with the caveat that a standing lug benefits from a stiff mast, so a hollow one must be sufficiently stiff to handle the high loads needed to flatten the sail as the wind picks up.

Steering is with a push-pull Scandinavian-style tiller attached to a yoke fixed to the head of the rudder. I have found this to work quite well. It is necessary to tie the tiller into the boat: if the tiller is dropped into the water untethered, it is quite an exercise to get it back while underway as it will be dragging behind the boat! I have also added a simple tiller tender, which I find very useful as it enables hands-free sailing for short periods.

The hull is both elegant and strong. I have dropped my Waterlust off a dolly onto concrete, and it appears none the worse for it. The ’glass-and-epoxy coating is very wear-resistant, which is useful on a boat meant for hauling-out on beaches. According to the specs, the fully rigged canoe should weigh about 115 lbs. I have not weighed mine, but I routinely walk about 800 yards to my launching beach with her on a dolly. I cannot, however, lift her onto a car roof without assistance of some kind.

An outrigger package is also available, and is put together in much the same way as the main hull. The crossbeam (or aka), which is laminated from four layers of 9mm ply, is reassuringly substantial. The outriggers are attached by lashing the crossbeam to mounting points fixed to the main hull and then bolting the floats or amas to the crossbeam. Each ama provides 70 lbs of buoyancy, which makes it possible to power-up the rig or simply have a more relaxing sail in gusty conditions. The amas touch the water at about 8 degrees of heel and, when the boat is flat, cause no drag at all as both sit clear of the water.

Courtesy of Chesapeake Light Craft

Courtesy of Chesapeake Light CraftA custom cane-back cockpit seat is the perfect addition for an easy sail in the gentle breeze of a late afternoon. The push-pull tiller and shorter balance-lug boom allow the skipper to sit facing forward and upright, while the Hobie MirageDrive provides some welcome auxiliary pedal power.

The whole package of outriggers and crossbeam weighs in at 27 lbs and is cleverly designed with storage in mind. The amas fit neatly inside the cockpit, and the aka, when lashed to the deck for storage, does not extend beyond the perimeter of the hull. This is very neat and a testament to the thoughtfulness and attention to detail of the designers, as it makes the package exceptionally easy to live with off the water, as well as on.

One of the great pleasures of sailing a canoe of this type is that it can be sailed from a seat, facing forward. I use a folding cane seat, which was recommended by Phil at Fyne Boat Kits, and I have been delighted with the choice. Although not officially part of the kit, this seat is the one shown in the illustrations in the CLC build manual. The height of the seat is important: it should be low for sailing, but I find it needs raising a little when paddling to allow me to get the blades comfortably in the water without hitting the gunwales. Although nothing is suggested in the build manual, two quickly removable wooden beams resting on the longitudinal stringers have proven to be an effective solution.

At its simplest, the Waterlust can be used as a canoe, powered by a drop-in MirageDrive, or a double-bladed or single-bladed paddle. I have opted for the paddles as I prioritize sailing over other forms of power, but I understand that the MirageDrive option works well, too, and can propel the boat at hull speed—over 6 knots has been measured. The plans also suggest that a sliding-seat rowing unit with outriggers could be installed.

For passagemaking under paddle, I raise the rudder, take out the daggerboard, and apply myself to my 240cm-long double-bladed paddle, which gives me a good reach over the relatively wide deck. With a loaded boat and no wind, I can comfortably cruise at 2 knots all day. As a canoe the Waterlust is stable when boarding and underway. It is comfortable and there is plenty of space to find a good sitting position. It’s no problem to stow the paddle, sit and enjoy the view, dig around to find the camera, or pour a cup of tea. This stable, beamy hull is well-suited as a platform for exploring or birdwatching: take the time to enjoy going slowly, and you will be rewarded.

A surprisingly versatile craft for one so small, the Waterlust canoe is equally suited to sailing or paddling.

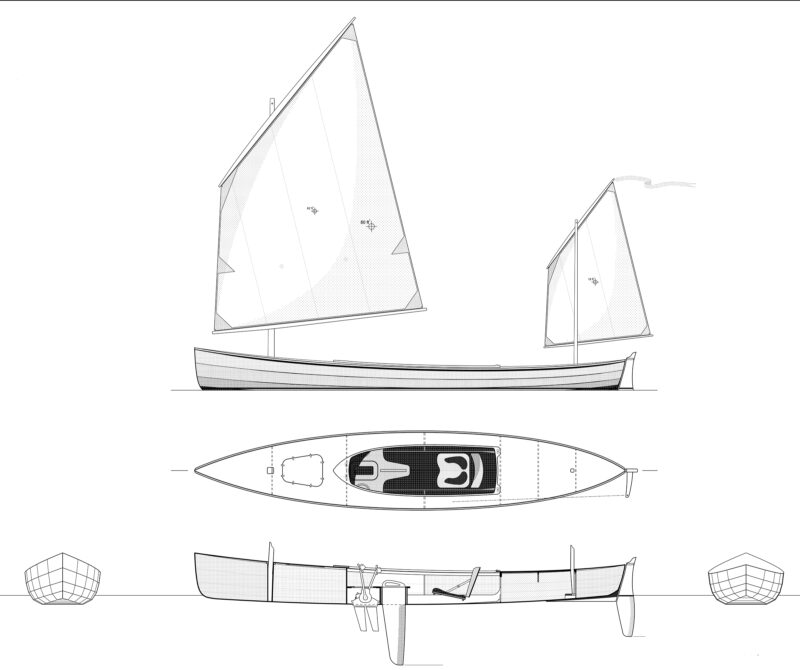

There are two maststeps forward for the 11′ 4″ mainmast, and one aft for the 6′ 10″ mizzen. The Waterlust can be sailed either with the main alone, a balanced lugsail of 62 sq ft set in the aft main maststep, or with the main set in the forward maststep and the 18-sq-ft mizzen added, taking the sail area up to 80 sq ft.

Handling the boat on land is a one-person job, though some may need help (or ingenuity) if the boat is to be transported on a car roof. For rigging I have found it best to get the hull in the water, or ideally drawn up on a beach where it will sit solidly on her flat bottom. The masts simply drop into their steps, then sails and daggerboard and rudder are made ready. This whole exercise takes me about 20 minutes, 10 minutes more if the outriggers are to be used. If using the outriggers, a beach is a much easier proposition than a pontoon or floating dock, as the outriggers get in the way and make tying to the dock a bit tricky.

The character of the Waterlust canoe under sail varies considerably depending on the choice of sails—main only or main plus mizzen—and whether the outriggers are deployed. Under main and mizzen and without the outriggers the Waterlust is a sporty proposition, and rapid reactions to changes in wind speed are called for. The sail area is slightly larger than that of a full-rigged Laser, and on a hull with a beam of 36″ (compared with the Laser’s 55″) hiking out as the wind strengthens is necessary to keep upright. When the wind pipes up, I find the sailing experience almost closer to windsurfing than dinghy sailing as one has a very immediate connection between the power in the sail and the counterbalancing weight of the skipper. While the rig can easily be matched to a steady breeze, rapid changes in wind strength are the main challenge. A capsize to windward if the wind drops suddenly is more likely than a capsize to leeward in a gust. It’s a lot of fun, though while gaining experience it would probably be best enjoyed with an empty boat in warm water. The addition of ballast has a marked calming effect; the canoe is an expedition boat, designed with carrying cruising gear in mind, and behaves well when loaded.

Courtesy of Chesapeake Light Craft

Courtesy of Chesapeake Light CraftWith its full decks, lapstrake hull, and split lug rig (technically a ketch but with the appearance of a yawl), the Waterlust harks back to the sailing canoes of the 19th century.

The outriggers are described by CLC as “training wheels to help keep the boat upright in gusty conditions” and do not convert the canoe into a fully fledged trimaran. Even so, the difference in character is substantial, and the sailing experience with the outriggers is more relaxing. The 70 lbs of buoyancy from each ama has a great impact on secondary stability, and the skipper can enjoy the best of canoe sailing safe in the knowledge the boat will stay right-side up under all but the most extreme situations. With the outriggers mounted, the Waterlust shows the best of itself as a well-thought-out cruising machine. When the canoe is being paddled, the amas are above the water and don’t add drag. When the wind fills in, the leeward outrigger gently limits the heel, with the righting force increasing as the ama is forced deeper into the water.

Tacking and jibing are straightforward with or without the outriggers, but it is important to enter a tack with sufficient speed to avoid being caught in irons. The remedy, if required, is a stroke or two with a paddle, and this is quickly done if the paddle is accessible. The use of auxiliary power when sailing is a great plus of this design, and either a single-bladed paddle or the MirageDrive serves well for this purpose. If beating in light airs to get round a headland to windward, I can pinch slightly and start paddling; this “paddle sailing” can be effective and perhaps avoid a tack or two.

Under sail with the outriggers mounted, the Waterlust skipper is free to enjoy the surroundings, and operations such as reefing, pouring coffee from a thermos, or looking at a chart are straightforward. I have even broken the golden rule of canoe sailing: never cleat the mainsheet. In the right conditions, I can make the mainsheet fast to the cleat I installed on the after face of the daggerboard case, engage a tiller tender to fix the rudder, and make long tacks with the canoe sailing itself.

For passagemaking, I plan for around 2 knots made good over the day, slightly faster with a fair wind. In a good following breeze of Force 3 or more, an average of well over 4 knots can be maintained for many hours. When sailing in company over an extended period, I found the Waterlust well-matched with a Welsford Navigator, and noticeably quicker than a Drascombe Lugger.

The Waterlust sails well under just the mainsail so the skipper has many options depending on the strength of wind.

The long hull is directionally stable and very forgiving with little tendency to broach even with a following sea. When significantly overpowered off the wind, the Waterlust remains remarkably docile and any tendency to roll is quickly dampened by the outriggers. The hull is easily driven, so reefing early does little to harm progress while making for a more comfortable ride. The deck protects the cockpit well, and I usually remain dry unless beating into a chop.

The Waterlust epitomizes the small-boat advantage: it is quick to build, easy to store, and light enough for one to handle alone. Because of its small size, all the hardware, sails, and spars are smaller, lighter, and less expensive than for a larger boat. It is a remarkably capable and, in my mind, elegant vessel.

The type is adaptable, and very much what you want to make of it: it can be a fast and exciting daysailer, a seaworthy expedition boat, or a platform for exploring. I know that many owners have adapted their Waterlust canoes to suit their own needs. Some make arrangements for a crew of two; others add ballast and reduce the sail area to make for more relaxed sailing without adding the outrigger package. I have stuck close to the standard package, usually using the outriggers and full rig, but I sometimes press my Waterlust into service as a paddling canoe with three or more kids on board, and it takes it all in stride.![]()

Guy Hall lives and sails on the west coast of Norway, near Bergen. In his youth he sailed extensively in the waters around the U.K. in boats large and small. His Waterlust canoe, christened SVALE, represents a first step back on the water after a career-induced break, and a way of introducing the next generation to the joys of small boats. He is a member of the Dinghy Cruising Association.

Waterlust Particulars

LOA 17′

Beam 36″

Draft 4″

Draft, board down 32″

Hull weight 115 lbs

Sail area, lug yawl 80 sq ft

Sail area, cat-rigged 62 sq ft

Maximum payload 400 lbs

The Waterlust Sailing Canoe is available from Chesapeake Light Craft as basic hull kit for $1,730. The sailing component kit is priced at $1,545, and the outrigger base kit at $598.

Building the Waterlust Sailing Canoe by Martin Cartwright is a 90-page book about what he, Guy Hall, and Stephen P. Clark learned while building their Waterlust canoes. It is available from Amazon for $18.85.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats readers would enjoy? Please email us your suggestions.

I have a Waterlust without amas and I find it great fun to sail sitting on the side deck with toes under the opposite deck, hiking. I can do this in 18 knots or so going to windward with reduced sail. Downwind in a breeze is far more challenging as it is so narrow. I tack downwind to avoid the rolling effect dead downwind. I only use the wicker seat when using the pedal drive.

A very adaptable fun craft that sounds even more flexible with the amas.

Being a gent of advancing years, I found the Waterlust a little too lively for me; and my cruising area – The Norfolk Broads, UK – (narrow tree-lined rivers and lakes), were not conducive to the use of outriggers.

Consequently, I reduced the size of the mainsail and replaced the lightweight plywood daggerboard with a 8mm steel one (detailed in my book).

The result is a wonderfully stable cruising vessel in which I have sailed calmly in 20 knots of wind without hiking out and slept on in safety and comfort during a 5-day trip to Holland last year. This is a truly versatile vessel whose looks draw admiring crowds wherever she sails.