Our 19′ wood-and-canvas freight canoe, a derelict whale of a boat I’d restored, is a bit of a pig for long-distance paddling, but Tina and I stay mindful of the weather, eat well, work a little, and take the time to enjoy the beauty and quiet around us. And happily tuckered out after a full day outdoors, we sleep well, too. Early in September of 2021, our longtime friends Richard and Jessica Johnson, with their nimble kayaks, joined us for five days of paddling on Umbagog Lake, which straddles the border between Maine and New Hampshire and is the southernmost lake in Rangeley Lakes chain.

We left the low, muddy launch site at the south end of the lake at about 2 p.m. and paddled northwest toward the north end of Big Island and one of the three dozen campsites maintained by Umbagog Lake State Park. Our 19′ canoe has a transom to take an outboard motor, but the gently rockered stern makes it possible to move right along when paddling if we put some muscle into it. There was an easy southwest breeze at the outset, but after the half-mile crossing of Sargent Cove and leaving the lee, whitecaps surged around us. We still had 2 miles to paddle into Thurston Cove, now into a headwind.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert .

Richard, in his yellow kayak, was out ahead scouting the shoreline for our campsite while Jessica kept us in view; we were trailing nearly 1/4 mile behind. The forecast was for a cold front to pass through in the afternoon and, right on cue, the sky turned as gray as a hornet’s nest, the temperature dropped, and the wind freshened. In the bow, Tina quickened her strokes to maintain headway and I switched to working my draw stroke hard on the starboard side to counteract the rollers and keep the big boat on course while quartering into the waves. When I paused to throw on my raincoat, the canoe spun quickly, the high freeboard acting as a sail. Putting our backs into it, we drew even with the northwest point of Big Island, where tall pines and spruce swayed in the gloom as the wind intensified, driving the slanting rain. To the east, Jessica, with Richard’s help, hauled her boat up the wet, black-rock shore of the campsite. Tina and I paddled farther windward before swinging downwind to ride the waves to the landing where Richard and Jess were waiting to catch our bow.

Tina and I slid over the gunwales into knee-high water and held the boat off the gravelly beach as the waves splashed against our legs, soaking our shorts. Tina pulled the Johnsons’ tent from under the canoe deck and chucked it up to them. We covered the canoe’s remaining cargo with a tarp as the rain angled across the wind and streamed across the tarp.

The canoe was side-to the rock-bound shore but was too heavy to lift. I hurled the 10-lb mushroom anchor offshore and secured the stern to its rode while Tina kept the bow off the rocks and held down the tarp. Richard and Jess got their four-man tent secured to its poles while the loose rainfly snapped like a whip. The gusting wind kept Tina and me focused on the canoe—our little anchor doesn’t hold well in a blow.

Tina DeVries

Tina DeVriesAfter landing at the campsite on Big Island, I tended to the canoe in the wind, trying to hold down the tarp to keep the firewood dry. It would take all four of us to carry the canoe to shore. This rock-strewn shore was no place to drag a heavy canvas-covered canoe.

With one tent up and the squall slackening, we offloaded the canoe, stashing open crates and totes in the tent and stacking dry bags and firewood nearby. Then, the four of us carried the freighter out of the water and set its canvas-covered hull on life jackets and seat cushions safely above the exposed rocks on shore.

Tina and I set up our two-man tent while Richard and Jess carried the gear stowed in their boats to their tent. The rain let up. They found the food bags and set out cheese and crackers. We heard the tinkling of ice in our camp mugs as they mixed drinks for happy hour. Soon, I had steak tips searing on the folding charcoal grill while the peppers and onions caramelized on the propane-fired griddle and quinoa and mushrooms simmered on the stove.

By early twilight the sky had cleared, and the evening cooled into a starlit night. I bundled up in warm pants and wool hat before we lazed in camp chairs, staring at the blue flames and orange coals of the dying fire. A loon’s song echoed around the lake.

Richard Johnson

Richard JohnsonAfter our first night at camp, we woke to a bright sun and a radiant blue sky. The exposed gray bedrock on the north end of Big Island is a common sight all around the lake.

In the morning, we fired up the camp stoves for French press coffee and oatmeal. After breakfast, Richard and Jessica tended to some leaky seams on their tent fly. Richard fashioned temporary drip rings for their paddles from twine and electrical tape to stand in for the originals, which he had forgotten to replace after varnishing the paddles. Jess sketched with colored pencils in her notebook while Tina rambled around the north end of Big Island and came back with news of dessert-plate-sized moose prints in the soft mud just 30 yards from our tent site.

We broke camp, then used the hand pump to empty the canoe of rainwater before the four of us lifted it back into the water and loaded it with firewood, coolers, backpacks, tents, kitchen supplies, fishing gear, spare paddles, water jug, and food bags.

Tina DeVries

Tina DeVriesRichard and Tom held the canoe off the rocks while waiting to load up for our excursion to Sunday Cove. The water was sweet-smelling and bracingly cold.

Tina and I got aboard and pulled away from Big Island, heading off for our day’s paddle to a campsite about 7 miles away at the northeastern end of the lake. Since our canoe was the slow boat, we got a head start while Richard and Jess finished stowing their gear and launched. They quickly caught up to us and paddled off along the shore, Jess with binoculars around her neck and Richard with a map under the bungees on his foredeck. We would meet for lunch at Molls Rock on the western shore. A west-southwest breeze gave us easy downwind paddling. The map showed a northeast heading to Metallak Island and then a jag north to make Molls Rock.

Richard Johnson

Richard JohnsonAfter an 11 a.m. start, Tina and I headed northeast from Big Island, paddling toward Metallak Island. The lake has a “bathtub ring” all around its perimeter because the water level was 4′ below normal.

By noon Tina and I were short-sleeved in the sunshine, and we found the paddling rhythmic and easy. Five loons floating nearby made mournful wavering calls, then dove out of sight. The wide-open lake basin stretched out along the evergreen hills dappled yellow and red with early touches of fall. The northern White Mountains rose to the south behind us, gray silhouettes beneath a bright sky. A blue heron stalked the shallows, fishing. I was fishing, too, trolling a small silver minnow lure. The pole bent and I quit paddling to set the hook and reel the line in. Tina netted the yellow perch as it rose to the surface by the canoe. Jessica was planning a chowder for our last night’s dinner, and we would add the fish to the pot.

We poked into Black Island Cove and made an easy landing on a soft, sandy beach on the north side. Wading in the ankle-deep water we saw hundreds of silver-dollar-sized freshwater clams and the curlicue grooves they trailed. After a stretch and a stroll, we boarded the boats again and continued, paddling around and between jutting boulders and exposed rock piles along the lake’s west side. We passed a few fishermen, their powerboats drifting with the wind in the shallows alongshore. Then, up ahead, we made out the prominent point of Molls Rock. Richard and Jess were already there and directed us to an easy landing on the bare-rock shelf at the water’s edge. To reach the top of Molls Rock, we walked up a worn granite incline. Clumps of green grass and a stunted spruce clung to the cracks and duff fringing the bare gray dome where names and initials had been carved into its knobbly top. The vista from 15′-high prominence swept from Tyler Point on our right up to Pine Point to the northeast. Beyond Pine Point and across the lake rose Johnson and Moose mountains.

To the northwest, the Magalloway River empties into Umbagog at the lake’s outlet and meets the Androscoggin River. The Floating Islands Bog lies between the rivers but as we left Molls Rock and headed north, we found the lake level too low to permit even the kayaks from progressing very far westward. Tina and I held back in the big canoe and skimmed over the clear shallows through lilies that twined around our paddle shafts. The muddy lakebed was close beneath us, but only rarely did we touch bottom with our paddles.

After traveling more than a mile north we turned east for the 2-mile run to our next campsite at the entrance of Sunday Cove. As we passed Pine Point, the afternoon wind picked up out of the west. In weed-free water now, I set to trolling again. The sky was nearly clear and bright blue as we rode downwind on the rising waves toward the 1/3-mile-wide mouth of the Rapid River. Richard and Jess paddled ahead along the shore to scout for the campsite. Tina and I saw only uninviting gravel and boulder landings and stayed a 1/4 mile offshore. Umbagog spans 8 miles from north to south and has an average depth of just 10′; it is deepest at the north end where it reaches down 50′ in spots. The west wind was blowing briskly across the 2 miles of open water behind us, and whitecapped waves swelled as the breeze freshened. As we waited for a sign from Richard, Tina and I labored to keep the bulky canoe on course and away from the lee shore.

In the distance we saw Richard land on the south side of the point at the entrance to Sunday Cove and manhandle his loaded kayak out of the water and up the rock-bound landing. He walked the shore of the peninsula looking for a better landing spot for the rest of us. Finding none, Richard waved Jess in and waded out to steady her kayak as she disembarked while it was still afloat. We then followed to the landing—a cove behind a wave-rounded natural breakwater, no larger than a compact-car-sized parking space. Paddling hard, broadside to the wind, we poked the bow of the canoe into the calm water just behind the rocks, letting the canoe swing slowly into shore where Jessica and Richard caught us. We managed our exit in thigh-deep water with wobbly rocks underfoot. Jess held the bow and Tina the stern as Richard and I offloaded the boat, tossing the firewood we carried high up the granite slope.

Tina DeVries

Tina DeVriesThe canoe was cushioned atop the rocks at the head of Sunday Cove. This view is due west toward the middle of Umbagog Lake.

The wind was lively, and the canoe bobbed in its tiny harbor. Jessica strained to keep the canoe off the rocks and was a little dumbfounded when she saw Tina reeling in the trolling rod. I had forgotten about the rod while controlling the boat and hadn’t brought in the lure before approaching the landing. At the end of the line was a fist-sized, mossy-green bass on the hook: more fish for the chowder! After steadying the rocking canoe, the four of us humped the canvas-skinned canoe up the rocky slope and onto the life jackets and seat cushions. There was a little yellow paint from Richard’s kayak streaked on the rock along the path he had taken.

The campsite was crowded with crooked white cedar and arrow-straight spruce, white pines with trunks as thick as whisky barrels, balsam firs as symmetrical as Christmas trees, and a hemlock with branches like inverted umbrella ribs. Red maples blocked the sky with their thick crowns of leaves, and white birch were charcoal black where horizontal strips of paper-white bark had curled back. The air had a spicy smell of cedar with a pungent turpentine whiff of pine. At the head of the cove to our south, the mixed forest and shrubs gave way to a small, open beach and shallow water.

In the morning the woods were suffused with a thick fog. Tina had gotten up early and was perched on the rocks peering through the murk toward the lake. As the sun rose, the fog burned off and, under an azure sky, all four of us boarded the canoe to paddle into Sunday Cove and search for the Carry Road. If we could find it, a 3-mile walk would take us to Forest Lodge where author Louise Dickinson Rich and her family lived in the 1930s, chronicled in We Took to the Woods. Paddling into the shallow head of the cove, we wallowed in sandal-sucking muck and carried the canoe, carefully hop-scotching rocks, to a berth on the boat cushions. A stream we could have crossed in a single stride trickled through the loose rocks and under a derelict timber-and-steel bridge overgrown with brush. We wove through tangled woods, around blowdowns and through tight stands of saplings. We found rusted remnants of metal buckets and heavy wire, but nothing that looked like a road much less a footpath. Before getting in too deep, we headed back to the lake and searched along the shoreline. With no sign of a trail there either, we returned to the canoe. I paddled while Tina and Jess settled between the thwarts and Richard stood in the bow, pointing the way through the maze of rocks in the shallows. As we paddled out of Sunday Cove, we considered turning south into the mouth of the Rapid River to look for the path, but the low water discouraged us from that, and we headed back to camp.

Tina trolled on the way out of the cove. The lake holds large brook trout and landlocked salmon, and I daydreamed about splitting a cedar log and grilling planked salmon for dinner. Tina got a strike and we stopped paddling while she played the fish. In a minute or two, she had it alongside the canoe and its silvery sides flashed just beneath the surface of the olive-green lake water. I hadn’t put the landing net aboard—this was to be a hiking trip—and when the not-too-tired fish came alongside the canoe, I tried to hoist it aboard by grabbing the line, but it shook itself free and swam away.

We spent the rest of the day relaxing in camp amidst the trees. Jessica and Tina strolled on the beach while Richard and I played cribbage. Tina lazed in her hammock; Jessica sketched; we swam. Later that afternoon, three otters came bobbing into our little bay. Loons warbled across the water to the south. A shrike, easily identified by its Zorro-like black mask, flitted through the tree limbs. Red squirrels nibbling on mushrooms chattered with rapid raspy barks.

That night, as the campfire faded and darkness surrounded our campsite, the Milky Way’s dusty glow appeared overhead. I spotted the Big Dipper just as a shooting star streaked across it. Far off to the west, beyond the lake, a jagged bolt of lightning flashed. As we zipped into our tents, rain fell with a whisper. Thunder rumbled through the night and rain pattered on and off.

By morning, water was trickling from the trees and the rain flies were soaked but the storm had passed. Cotton-white clouds draped the western hills and there was a faint southwest breeze. Tina and Richard were up early, standing at the edge of the lake watching the otter family swimming and diving a mere 10′ away. A doe and two fawns with white-speckled backs sauntered across the beach. We stood in our raincoats under the dripping evergreens during our breakfast of coffee and granola. After breaking camp and loading up, we paddled away on mirror-like water.

Tom DeVries

Tom DeVries Jessica and Tina enjoyed breakfast while lounging in rain pants on the damp granite. Looking through binoculars to the far-off hills in the west, we could see dozens of wind turbines harnessing the wind that blows across the hills by the lake.

Tina and I floated westward back toward Pine Point in the flat calm. The still morning air, thick with humidity, hung in a thin chalky haze over the lake. Fish, sipping flies, left dimples on the water. I could occasionally get one to follow a lure in toward the canoe, but then it would drift off when it got close to us.

Tina DeVries

Tina DeVriesJessica and Richard drifted past Pine Point. An old-time summer camp sits back in the woods.

After we rounded the northernmost prominence of Pine Point, we had 4 more miles of paddling south to round Tyler Point and reach a campsite inside Tyler Cove. The weather was quiet, with no appreciable wind, either with or against us. Loons laughed and swam nearby. A bald eagle looked down on us from its tree-branch perch. We paddled languidly and it seemed a long, sleepy haul.

Tom DeVries

Tom DeVriesTina provided forward momentum as we made our way northeast toward Tyler Point. In our cargo canoe we don’t need to travel light.

At length we reached the landing at Tyler Cove. We slowly drifted over the shallows and nosed the canoe gently onto the sandy beach. Rain was likely to fall in the afternoon, so we set up the tents and hung the flies, still damp from last night’s rain, to dry before putting them on the tents. Using the kayak paddles as poles, we set up our tarp over the campsite picnic table.

Tom DeVries

Tom DeVriesJessica and Richard carried his loaded kayak to a soft landing at the campsite on Tyler Cove.

Jessica made fish chowder with the fillets of the fish we had caught and, although there may have been more canned corn in the chowder than fish, it made a delicious dinner. Rain spattered lightly as we drifted into our tents.

Richard Johnson

Richard JohnsonLow water in Tyler Cove left a wide, sandy beach. The view here looks southeast, with Metallak Island peeking out on the right.

On the last morning, we woke early to a gray dawn with drizzle speckling the lake. Tina, Jess, and I, still a little foggy-eyed, strolled southeast to a bog surrounded by blueberry bushes, balsam fir, and white birch. After a breakfast of oatmeal, grilled bread, and coffee we watched a family of three loons swimming 10 yards offshore. The elders were diving and bringing up food (freshwater clams, perhaps) to feed their youngster. The young one stuck its head under water but never dove and the parents whistled softly to each other as they fed the little one.

Jessica Johnson

Jessica JohnsonAt the trip’s end, Tina and I returned to the Umbagog Lake Campground boat launch. We powered the canoe with classic cedar beavertail paddles.

We loaded up and, although it was easy to shove the canoe off the sandy beach, once out on the lake, Tina and I were blown backward by the stiff northwest breeze. We settled in and bulled our way through the whitecapped waters to the lee of 150-yard-long Metallak Island. After a breather we ran southwest, back toward Big Island, with the wind aft on our starboard quarter. Rounding Tidswell Point, Richard and Jess rejoined us, and we drifted awhile downwind, lolling in the surf with the whole of Umbagog Lake behind us. ![]()

Tom DeVries and his wife Tina live in New Braintree, Massachusetts. He enjoys fruitful days spent in Beyond Yukon Boat and Oar, his snug woodworking shop. In years gone by, Tom has also canoed on the Yukon, fished commercially in Alaska, and sailed his skipjack on the Chesapeake. He wrote about his 1986 river travels in Zaire in the May 2019 issue. He wishes to thank Bob Lavertue of Springfield Fan Centerboard Company for the gift of the freight canoe four years ago.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

My wife and I did a reverse version of this trip around 35 years ago, from Bugle Cove on Mooselookmeguntic to Middle Dam on lower Richardson, in a Mansfield canoe with an old Johnson 3-horse on a side bracket. A bit crazy, but we were young and (I was) foolish. Those are big lakes, with big wind and waves, but it was a memorable journey. We did get to see Forest Lodge, the inspiration for the whole project.

We’ll make our way back some day to find Forest Lodge. Looking at the Northern Forest Canoe Trail map I see the portage trail along the north side of Rapid River leads you there. And it would certainly be good to start where you did, Greig, and explore more of the Rangeley Lakes region. On our visit to Umbagog, a pleasant park ranger told us he had a boat similar in size to ours that he powered with a 2 1/2-horse motor and he comfortably made his way on all the big lakes of western Maine.

Tom, thanks for a great narrative that satisfies all of one’s senses. Umbagog sounds a lot like Lac St. Francois just to the north in Quebec, with rocky lee shores aplenty. I’ve been tinkering with various methods of anchoring off or being able to pull our craft up on the shingle with airbags. Thoughts?

Thank you, Jim.

Camping on shore, I’ve always felt better having my boat nearby on dry ground. But scrapes and dings are inevitable. I remember patching a crack in a wooden canoe on the Yukon River with chopped dog hair mixed in melted spruce resin.

I don’t have beach rollers, but think they would be a good addition to our freight canoe kit, especially as our dead-lift ability fades with age.

I would recommend Chris Cunningham’s July 2021 article on clothesline anchoring for a possible off shore solution.

Wow – the memories triggered by your rendition of the trip! Raised in the upper Androscoggin valley, years of cruising and camping on Umbagog and the upriver lakes in all their moods have been a wonderful and, yes, a spiritual part of my life. Thanks!

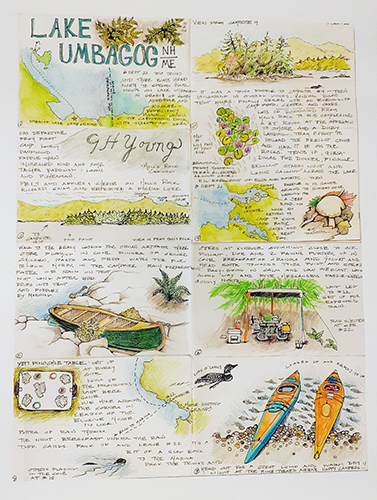

This poster is Jessica’s sketch of our Umbagog trip.