My kayaking trip to Croatia in 2005 got off to a rough start. During the first day, crossing swell on the Adriatic made for seas so steep and confused that seasickness slowed me to a crawl, and that night a storm brought lightning ground strikes and winds of 40 knots, flattening my guide’s tent and forcing us to retreat from the open ground where we’d camped to find shelter. It made for a good story, the kind I was used to writing about: facing challenges. The trip ended well, and in a way that I grew to appreciate the more I traveled in small boats: chance meetings with remarkable strangers.

Radovan and I arrived at Kozarica on the morning of our last day of a kayak tour of the Elafiti Islands near Dubrovnik and Mjlet Island. We stopped in Kozarica to stretch our legs.

My guide Radovan and I were on our final day, paddling along the north coast of Mljet, a slender 19-mile-long island, 4 miles off the Croatian coast and 15 miles northwest of the city of Dubrovnik. We stopped at Kozarica, a village of only a dozen buildings nestled between its harbor and the steep wooded slope of the ridge that runs the length of the island. We landed on a gravelly beach tucked in the inner corner of the harbor and pulled the kayaks ashore between the handful of open fishing boats hauled out there.

It seemed that everything on the coast was made of stone: buildings, roadways, and fences. The Croatian limestone is easily worked and yet water resistant, so it’s not as prone to dissolve as other types of limestone. The White House’s columns are made of it.

The village was quiet, and Radovan and I were alone for several minutes, before a man wearing a blue coat and a yellow baseball cap emerged from a passageway between the harborside buildings. He walked up to us; I said Dobar dan—good afternoon—one of the few bits of Croatian I’d picked up. He nodded. Radovan spoke with him in Croatian and translated for me. His name was Pero, but he was called Brko, the mustached guy. He had a weather-creased face, deep-set brown eyes, and a short black beard showing the first signs of turning gray. Beneath his coat, showing below his throat, he had on a white sweatshirt, a green plaid shirt, and a T-shirt.

The residents of Kozarica didn’t build their village to accommodate cars, so there were more passages like this than roads. Brko’s kitchen and bedroom were in separate buildings, so these public walkways were also the hallways of his home.

It was early in the morning and Brko invited us for breakfast, so we followed him to a 4′-wide alley that led to his kitchen, a single room with just the one door from the outside—he slept in a room in another building. The kitchen’s two windows were darkened by shutters and the room was lit by a bare light bulb hanging from the ceiling, casting sharp-edged shadows on the walls. The floor was a foot deep with juniper boughs. Brko motioned for me to sit at the table in the seat where he had been eating breakfast. I sat down to a white enamel bowl and the jaw of a pig, leathery brown with a row of teeth facing me and half of a lip curled back over a bed of dark boiled greens. Brko, talking to Radovan, pointed to a picture on the wall. It was of Croatia’s president on a visit to Kozarica and behind him stood a beaming Brko. Taped to the opposite wall was a year-old poster-sized calendar with a photograph of a woman leaning against shelves of wine bottles and wearing tight white shorts and a pair of silver stars. Hung from a cupboard knob by a piece of blue plastic twine was a leg of ham, which Brko had been slicing away at.

He set a frying pan on the stove, poured in 1/2″ of green olive oil, and picked two eggs out of a box on the floor—one white, the other brown, its shell as lumpy as alligator skin. While the eggs were bubbling in the hot oil, Pero pulled a block of cheese out of a bucket, scraped off a gummy gray outer layer and sliced thin shavings onto our plates. He served the eggs, sunny side up, glistening with a sheen of oil.

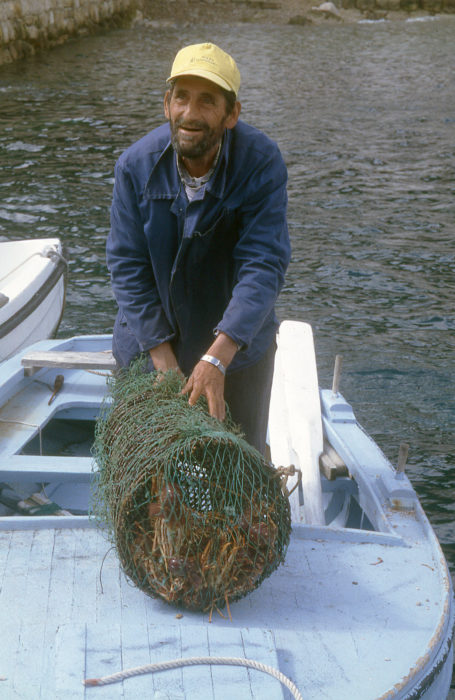

The traps that Brko and others made were scattered around the perimeter of the harbor. This type of trap, called a vrša, is made with split juniper withies and wire.

I asked Brko about the boughs lying on the floor. They were for making lobster traps. I had seen several of the traps at the edge of the harbor. They were about 5′ long and the diameter of a basketball hoop. Split boughs were woven in a tight pattern of triangles on the cylinder walls and in opposing spirals at the ends, like the pattern of a sunflower’s seed head.

The vrša has its origins in antiquity, and while it remains effective for catching lobster and fish, it is also popular with tourists as a decorative item.

Brko said it took him two days to make a trap. As intricate as they were, I would have thought they would take much longer. They were as much works of art as utilitarian objects. The outer shell came to a domed end and two funnels of woven withies inside the cylinder would lead the lobsters in and keep them in. The layers of juniper withies, bent in spirals and circles and bound with thin galvanized wire, created mesmerizing patterns in an elegant form that I would be happy to have in my living room.

Hanging on the wall by the kitchen door was a hooked tool for harvesting the boughs. Next to it was an adze, a small and simple tool with a blackened steel blade. If there had been a hardware store in town that carried them, I would have bought one. I asked Radovan if it would be inappropriate to ask Brko if I could buy his. Radovan translated for me and Brko, answered, “No, I need that. It’s a good one that I bought on a market day in Dubrovnik on the Day of Saint Blaise, the town’s patron saint.” It was just the kind of answer I’d give to anyone who might ask to buy any of my tools. A tool that’s useful, feels good in the hand, and has history can’t be replaced at any price.

Brko was popular with the cats in Kozarica. This one-eye black cat was just one of the cats that sought out his company while we were there.

As Radovan and I ate, a black cat, its right eye swollen closed, came into the kitchen and leaned up against Brko’s leg. He stooped down and cupped his hand over its head and spoke to it in a high, sweet voice.

Brko’s boat was built by his brother. The two of them, each in their own boat, row from the harbor to set lobster traps and fish the waters around Kozarica.

After breakfast, Brko took us back to the harbor to check on one of the traps he’d set there. His boat, built by his brother, had a white hull and a light blue sheerstrake and deck. He pointed to a boat just like it, resting on the beach by our kayaks, built by his brother for his own use. The trap Brko pulled up had been sitting right under his boat where it was tied to the dock. It had a dozen lobsters in it—it was clearly as effective as it was beautiful. Brko had wrapped it in green fish net when he’d returned to the harbor to keep the day’s catch securely stored.

Brko had kept a day’s catch of lobsters alive overnight by keeping them in one of his traps, hung over the side of his boat. The netting prevented any from escaping.

Radovan and I had to get underway again to meet our rendezvous at the west end of Mljet. As Brko walked us back to our kayaks, a little girl with short blonde hair and dark sullen eyes ran up to Pero and wrapped her arms around his knees. He put his hand on her shoulder and spoke to her in the same sweet voice he’d spoken to the cat. I said goodbye—Dovidenja—and shook his hand. His grip was gentle and his hands surprisingly soft for all the work he does with them. Brko said goodbye to us, and bowed his head toward the girl as the two held hands and walked away along the stone-paved street, deep in conversation.

As Radovan and I were saying goodbye to Brko, this little girl came up to him and wrapped her arms around his legs. He was an unassuming man who left a deep impression on me for his craftsmanship, generosity, kindness, and warmth.

Thanks for the glimpse into seaside village life in Croatia at that time.

I can’t help but think of all the other stories latent in that little vignette of the bay that morning. What is the economic basis for life in that village? How important is the lobster fishery to the locals – does it go beyond food for immediate consumption for the villagers or is there a market? The implication of the apparent lobster abundance in the bay is that the water is clean and that there must be effective sewage treatment or at least the outfall is offshore. Is the art and craft of trap making being passed on to the younger generation? What is the history of the boat type built by Brko’s brother?

I think you’ll have to return there and come back to tell us what you discovered.

Chris,

It’s a muggy Sunday morning here and Tina and I have just been transported to a calm, lovely place. The magic of Brko’s snug stone harbor was a delightful departure from squalls, swells, and seasick ‘yakking.

The photos from your visit – man with a yellow hat, one-eyed cat, wicker lobster traps, stout wooden boats, stone and stucco, sweet little girl, placid waters – as well as the vivid telling of a stranger’s gentle kindness reminded us that a lot of little connections out there are what brings us all together. It also put me in mind to re-read the story of your visit with the Hubbards that you shared in SBM in March, 2017.

Your sweet, colored memory of getting off the water pulled up one for me. We were boat-hiking down the Rio Napo on summer break from teaching in Quito and had found a new ride to take us across the border into Peru. Waiting for the boatman to cast off the dugout, my friend Paul spotted an older native woman washing clothes at the river’s edge. His hands moved to his waist to extract a small, travel camera from the Velcroed pouch. The swoosh of Velcro teeth separating brought up the woman’s head and she turned her back to us as she walked away. No photo but an enduring memory of a woman’s heightened threat awareness. We never reached the Amazon (house arrest in Peru) but those 50 years ago memories are easily refreshed. Thanks, Chris.