My love for Phil Thiel’s Friend·Ship canalboat began in September 2011 when I read an article by Christopher Cunningham about Phil’s quiet and simple boats (WoodenBoat No. 222). I reread the article multiple times and daydreamed about the day that I could have a floating RV on which my whole family could live aboard for extended lengths of time. Harry Bryan’s article on shanty boats in WoodenBoat No. 224 pushed me into action, and I called Phil to purchase the plans for his Friend·Ship.

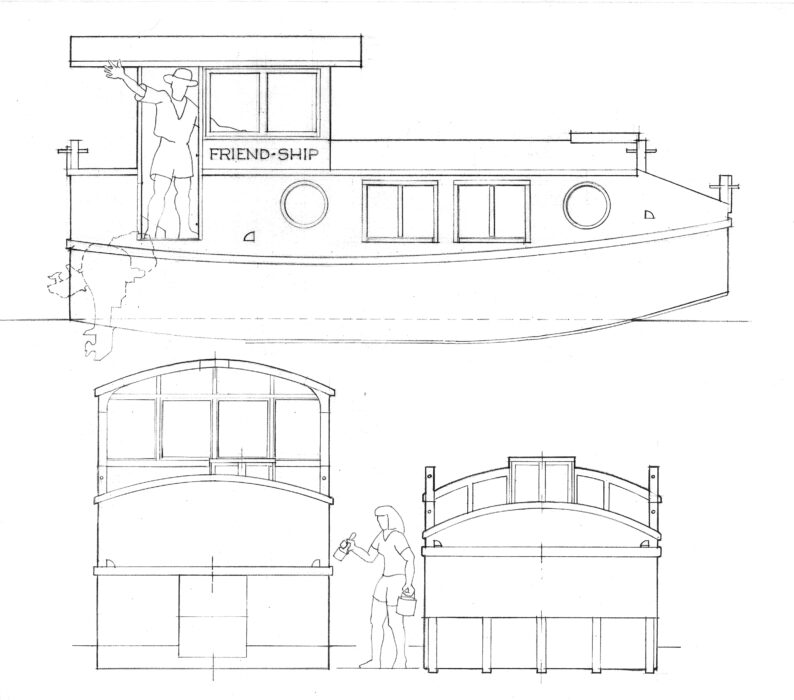

Our first call was interesting, as he asked me why I wanted the plans and if I understood the purpose of the design. While Lake Ontario is literally at my back door, its open water is not what the Friend·Ship is meant for. I explained to Phil that the province of Ontario has hundreds of kilometers of canals and rivers and small lakes for which the Friend·Ship would be perfect. Satisfied by my response, Phil sold me a set of plans. They included one page of written instructions, construction specifications, building procedures, and 13 pages composed of measured drawings and joinery details.

I pored over the plans and used the scaled frame drawings as full-sized patterns to build a 23″ model at 1:12 scale to visualize how the boat would go together and how it would look completed. I sent pictures of my model to Phil, and he loved it.

Beth and James Kenney

Beth and James KenneyThe plans leave the wheelhouse outfitting up to the builder. The companionway hatch can be raised for easier access to the cabin.

The building procedures for the Friend·Ship were the same as those used for his smaller canal cruisers like the Escargot and L’Ark. The assembled frames are to be erected upside down on a level floor and the hull and sides completed from bottom up to the roof line in that position. The plans are clear and detailed and the construction is uncomplicated with just a few simple curves—one for both the wheelhouse and cabin roofs and one at each end of the hull. At 23′ long, 8′ wide, and 10′ 6″ high, the Friend·Ship is as large as my whole dining room and would need an even larger space to complete the work or turn the hull over.

Phil had calculated that the flip-over weight of the completed hull—without the roof, wheelhouse, and interior structures—would be between 1,000 and 1,400 lbs. My several readings of the plans convinced me that most amateur builders, including myself, could not build the Friend·Ship hull upside down and then roll it upright. Phil told me that he had sold lots of plans, but at that time he knew of no one who had built the Friend·Ship as planned. (A Tennessee-based Friend·Ship builder was able to roll-over his completed hull using slings and chain hoists. In anticipation of the boatbuilding project, he had built a 30′ × 45′ workshop with a 16′ ceiling. —Ed.)

I told Phil that I planned to build the frames, then cut each one into two pieces along a line 3′ above the baseline of the boat’s bottom. I could then build the bottom on a ladder building form which would place the bottom only 4′ above my driveway. After I finished it with epoxy, ’glass, paint, and rub strips, I could roll the hull upright with roughly half the effort and half the space rolling the whole boat would require. With the hull portion upright, I’d reassemble the frames, top to bottom, and finish the upper half of the boat. Phil gave his approval and wished me success.

Beth and James Kenney

Beth and James KenneyThe dining table can be lowered to rest on bench-front cleats to create a double berth. Under the countertop stove, the galley has an open space for a portable cooler.

I also needed to study how I would use the boat. The rivers and canals in my area would be miles from the house, so the boat would live on a trailer. To keep the boat and its projecting sheer guard and roof eaves within the 8′ width limit on the highway, I reduced the overall hull width from the designed beam of 8′ to 7′ 8″. I then designed a flatbed trailer specifically for the Friend·Ship and had it constructed by a local trailer builder while I worked on the boat.

As directed by the instructions, I used spruce 2x4s from the local lumberyard for the framing and 44 sheets of marine plywood: 1⁄2″ for the bottom, 3⁄8″ for the sides, and 1⁄4″ for the cabin and wheelhouse roofs. I bought enough epoxy to coat every surface of the hull both inside and out.

During the winter of 2018, I completed and cut the frames in my basement, and in August 2019 I started construction of the bottom of the hull in my driveway. The ladder building form placed the plywood bottom only 4′ off my driveway.

After completing the hull, including epoxy, fiberglass, paint, and rub strips, I could, with helpful neighbors, flip it right-side up, rejoin the frames, and complete the boat. In August 2021, the completed hull was on its trailer, and I launched it to check for leaks. After spending a year working on steering, power, electrics, wheelhouse, interior finishes, and other details while the hull remained on the stabilized trailer, I launched the fully finished boat, weighing an estimated 2,200 lbs, and made its first test run in August 2022. A small open foredeck allows for sitting, handling mooring lines, and storage of external propane tanks and anchoring gear. A hatch and twin doors with screened vents lead down a ladder to the forward cabin where the single 6′ bunks on either side are curtained off from the main cabin and have storage underneath. Between the bunks there is a 3′ by 4′ area with 6′ standing headroom and space to turn around. Large round windows, port and starboard as specified, provide excellent lighting.

Beth and James Kenney

Beth and James KenneyThe forward compartment houses two single berths. The ladder provides access to the foredeck.

The main cabin has a dining table and two benches with storage beneath them, and lowering the tabletop to bench level makes a 6′-long double berth on the port side. The galley on the starboard side has a sink, with countertop on either side of it for a propane stove and meal preparation. Underneath, there is a cabinet for storage and an open space for a large portable cooler. This cabin has over 6′ headroom and two windows on either side which slide open for light and ventilation. I built the sliding windows exactly to the detailed plans and they work very well. They have 1⁄4″ acrylic panes and screens installed on the outside.

In the plans, the head is on the starboard side directly aft of the galley. At the request of the first mate, I moved the front wall of the head forward by 6″ to accommodate the installation of a self-contained composting toilet, which needs a bit more room than a portable toilet requires.

On the port side, aft of the dining area, is a 6′-long double berth with the foot of the bed extended beneath the floor of the wheelhouse. A fixed round window over the head of the bed illuminates the space and provides a view to the outside.

Beth and James Kenney

Beth and James KenneyThe foot of the double berth in the stern is tucked under the wheelhouse deck.

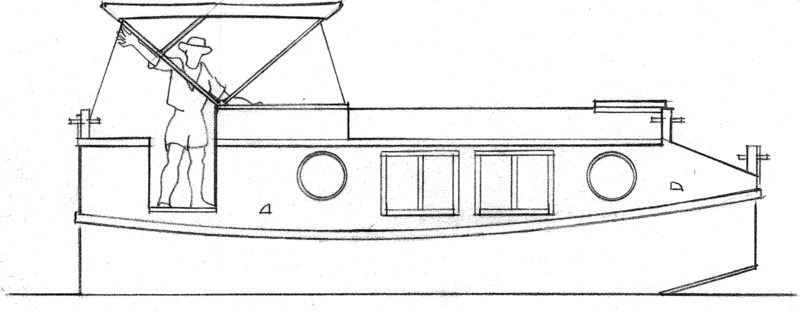

A four-step ladder leads from the main cabin up to the wheelhouse, which occupies the back 6′ of the Friend·Ship. The top of the wheelhouse is removable and allows for raising and lowering the boat’s profile for reduced windage when trailering long distances, and ease of wrapping for winter storage. It weighs about 150 lbs, which makes it a task for two or more strong people. In the future, I hope to design a mechanism to handle this job in a more practical manner.

The wheelhouse has two box seats at the transom, one for gasoline storage and the second for safety equipment. Between them, I changed the motor cover into a step/seat allowing access to the swim ladder that’s mounted on the curved transom leading down to the swim platform I added across the stern. The platform is hinged to pivot against the transom when not in use.

The shelf flanking the companionway at the forward end of the wheelhouse has room for navigation instruments. I installed an illuminated compass and video monitor connected to a camera at the bow, which allows the skipper to check the blind spot directly in front of the boat.

The plans leave it up to the builder to make the arrangements at the helm. My steering has a single-cable steering link that snakes under the wheelhouse floor and connects with the motor from the starboard side. On the port side I installed a 100-year-old 36″ wooden steering wheel. I’m only one step away from the wheel and motor controls, even when looking out from the wheelhouse along the starboard side.

Beth and James Kenney

Beth and James KenneyOn the starboard side, aft of the galley is a curtained compartment for the head. The ladder leads to the wheelhouse where a storage box serves as a seat. To its right, the cover for the outboard is built with a step to climb over the transom.

On that starboard side, under the wheelhouse floor, I installed the electric panel, with two batteries: one for house power and the second for starting the outboard. This space is accessed by setting aside the ladder to the wheelhouse.

When registering my Friend·Ship, I learned that state regulations require a secondary manual-propulsion system. My solution was to build a 14′-long sculling oar of white ash which is inserted through a hole in the center of the transom just above the floor of the wheelhouse. I keep it stored along the underside of the wheelhouse roof with the handle projecting through a hole in the wall forward and a few inches of the blade extending aft just past the roof. My estimate for the towing weight was 3,500 lbs including the motor, interior fittings, and trailer. I used a six-cylinder Chevrolet van for towing and the boat easily followed, but with only front-wheel drive, I quickly learned it didn’t have the traction to pull the loaded trailer up the launch ramps, so I upgraded to a four-wheel-drive Ram pickup truck, which handles all the demands.

Although the Friend·Ship looks like a large vessel, it is light for its size and about as easy to haul, launch, and retrieve as if it were a much smaller boat.

The plans recommend an outboard of 5 to 10 hp; I installed a 9.8-hp four-stroke with remote controls and a high-thrust propeller. The four-stroke option has proved to be quiet and highly fuel-efficient. At cruising speed with the motor cover in place we can hold conversations in the wheelhouse without raising our voices. A single 3.17 U.S. gallon tank of gasoline provides more than 11 hours of cruising.

Charlene Mitchell

Charlene MitchellFor those who prefer open-air boating, the plans include an option for a folding bimini in lieu of the wheelhouse. The transom ladder and folding swim step are an individual addition.

The 9.8-hp motor can push the Friend·Ship at 5 knots, which is 1 knot under the theoretical hull speed for a 19′ 6″ waterline. Backing off to three-fourths throttle the speed drops to a steady 4 knots. Even reducing to half throttle, we were able to maintain the constant 4 knots. At one-third throttle the boat maintains a miles-eating 3-knot cruising speed. We can run a 10-hour day of cruising on less than a tank of gasoline. I often smile as boats costing 10 times as much fly by, because we will both eventually end up at the same location.

On our first cruise, the Friend·Ship struggled to hold a heading as the stern would slide side to side, requiring helm turns, lock-to-lock, to try to maintain course. Thiel’s smaller barge-hulled canal boats, the Escargot and the JoliBoat, each have a skeg on the centerline, but that element isn’t included in the Friend·Ship plans. While a similar single skeg would have been adequate to give the hull directional stability, I could not easily install a skeg on the centerline with the boat sitting on the trailer, so I designed twin skegs that I could through-bolt to the framing members on either side of the motorwell. The skegs are 7′ long, 1 1⁄2″ thick, and 7 1⁄2″ deep at the stern and 1 1⁄2″ proud of the hull at their forward ends. The skegs work well, provide full control to the helm, and the boat now follows a heading like a train on rails.

Charlene Mitchell

Charlene MitchellFor trailering or storage, the wheelhouse roof is deigned to be lowered. The window sashes are all installed with loose-pin hinges, top and bottom, and can be removed and stowed in the cabin. The posts supporting the aft end of the roof are also demountable.

The Friend·Ship can easily accommodate six to seven family members for day trips and has berths for six for overnight outings. It is a perfect boat for long, leisurely trips on sheltered small lakes, rivers, or canals. I have even used it on Lake Ontario during times of calm or light winds while keeping an eye on the weather.

Building Friend·Ship is well within the abilities of woodworkers with modest abilities, even without a large shop or construction site. My estimated cost was $15,000 CDN ($11,000 USD) including both the trailer and motor. The Friend·Ship is truly a trim and proper little ship that turns heads everywhere we go, both on the road and in the water.![]()

James Kenney of Burlington, Ontario, studied mechanical engineering in college and retired in 1999 from a successful 34-year career as an international marketing manager to open a martial arts school. Now an 8th Dan black belt, he still teaches over 25 hour per week. At the age of 10 he received his first boat, a wooden semi-dory rowboat, which he later converted to sail. The Friend·Ship was James’s seventh completed wooden boat project. Now entering his 80s, he may have one more small-boat project in him (with his first mate’s approval).

Friend·Ship Particulars

Length: 22′ 9″

Beam: 8′

Draft: 9″

Height above waterline: 9′ 9″

Power 5 to 10 hp

Phil Thiel passed away in 2014, and plans for the Friend·Ship are now available from The WoodenBoat Store for $75.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats readers would enjoy? Please email us your suggestions.

I like it! What is the top speed of it when loaded with your cruising gear and supplies. 3 knots is ok, but if a current or headwind is encountered…….

Even with 7 people on board my 9.8-hp motor is able to push the boat at 5 knots at max throttle. The Friendship is for leisurely cruising, if it is too windy, seek a close harbour.

Jim

Insightful article about a great build – thank you for sharing your experience.

Thanks for your comments. I found the article harder to write than actually building the boat. But now both are done.

Jim

Very sweet. Feels like a canal boat influenced by the ’30s flush-deck cruisers. An elegant twist on the usually down-homey canal boats.

A friend and I were looking at a similar sort of concept on the Cumberland River in TN a few days ago. A 25′ manufactured aluminum box, reminded me of a Gibson style house boat influenced by one of the new hyper-mini pickups. Has everything a Gibson has, except air past your elbows. I asked my friend: “How would you emphasize that? Is it a Tinyhouse boat, or is it a Tiny Houseboat?”

He thought for a minute, and said: “Its a River RV. A RiVer.”

Be a good name, if another reader builds one.

Thanks for your comment. A self-propelled river RV is what it is. You can still buy the plans from Wooden Boat Magazine for $75.00 and save yourself a lot of money, if you have the time.

Jim