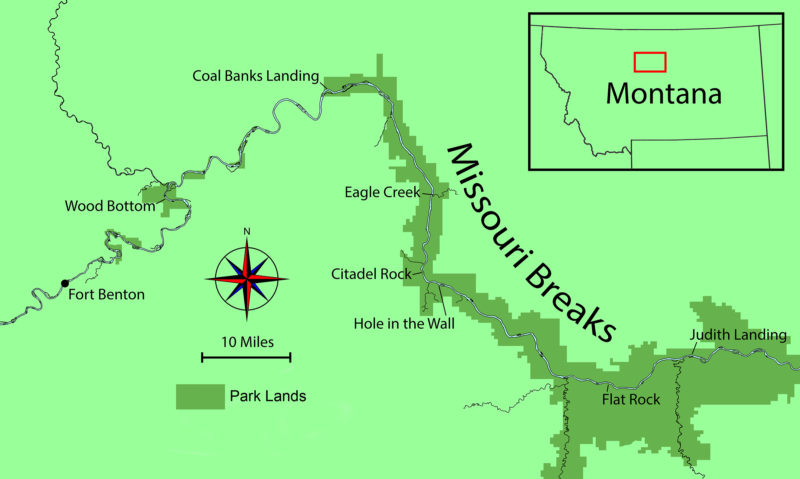

On the rusty old trailer behind my car was NEWT, a 15′ solar-powered micro cruiser that would be my little floating home for the coming week. NEWT had proven herself last summer during a month-long cruise through Washington’s Puget Sound, among cities, restaurants, museums, and crowds of luxury yachts. This year, I was looking forward to a much more solitary and rural river trip in the Missouri Breaks National Monument.

All photographs by the author

All photographs by the authorWith NEWT in tow, I drove about 450 miles from my home in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan to get to the Missouri River. I stopped in Cadillac, a shadow of the boom times 80 years ago. Dilapidated buildings, wrecked cars, and an abandoned grain elevator slumber along a highway that runs from horizon to horizon through the yellow and green fields of grain. I was happy to get a tank of gas from the part-time station proprietor/farmer wearing a John Deere hat.

I arrived at Fort Benton, Montana, the usual starting place for drifting down the Missouri River, late in the evening. It was dark and raining hard as I pulled into the local campground. With NEWT still perched high on her trailer, I set up the cockpit tent, which was quickly soaked, and the interior soon became equally wet as I awkwardly crawled in over the gunwale with soggy clothing and muddy shoes. Getting things sorted out and arranged for the night was like playing Tetris in a leaky garbage can. As I drifted to sleep, I was hoping that the weather in the morning would be better.

When I woke up the sky was still gray and foreboding, but it was time to go. The squishy, wet cockpit tent made a gurgling noise as I rolled it up and shoved it into its sack. The car was dry and the fast-food breakfast was hot as I drove about 18 miles downriver to launch at Wood Bottom Campground. It had begun to rain again and the boat launch was quite uninviting—gray, muddy, and deserted.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

NEWT would have made an odd sight—if there had been anyone to see—as I backed the trailer down the slippery ramp. My daughter and I had built the hull several years ago, a Chester Yawl kit from Chesapeake Light Craft. In preparation for my Puget Sound trip, I had modified it with arched decks fore and aft, leaving space for a small cockpit in the middle. The decks are covered with high-efficiency solar cells that can generate 400 watts, enough electricity for a customized trolling motor to drive the boat indefinitely at about 5 mph on sunny days. Lithium phosphate batteries provide about 4 hours cruising in reserve for cloudy days and early mornings. A small tent covers the cockpit to provide a small but cozy sleeping area.

I launched in the rain at the Wood Bottom Campground. When I returned at the end of the week, I found the road barricaded and the parking lot flooded. I just barely retrieved my car and trailer.

I slid the boat into the swampy water and parked the car and trailer in a corner away from the river, hoping that the favorable weather forecast for the rest of the week would prove accurate. The forecast for the river conditions, however, was not at all favorable. The ranger in the campground’s interpretive center warned me that the river flow, controlled by an upstream dam, was three times above normal for this time of year. This would cause very strong currents, water levels 3′ or 4′ above normal, and there would be plenty of debris in the water, everything from small grass and weed that would foul my propeller to huge tree trunks that could put a hole in my boat. The high water had brought the normally busy guiding and touring business to a standstill, and I would be all alone on the river for the week.

I waded into the turbid and swirling water, climbed into NEWT, and pushed off. The power of the current was immediately evident; before I could even get an oar in place, it pulled the boat toward the soggy and flooded shoreline. A few hard pushes got me out to the middle of the stream, and before I knew what was happening NEWT was swept under a bridge 3/4 mile downstream. As I flew by it, I caught a glimpse of hundreds of swallow’s nests—circular, muddy, smooth caves underneath the bridge.

After a few minutes, things settled down and I began to notice the landscape around the river. The banks were low, grassy, and dark green under the cloudy skies, backed by low rounded hills in the distance. The water was murky brown with small vortices visible throughout the entire surface. With my throttle set for cruising, I was heading downriver at about 10 mph. This was going to be a fast trip.

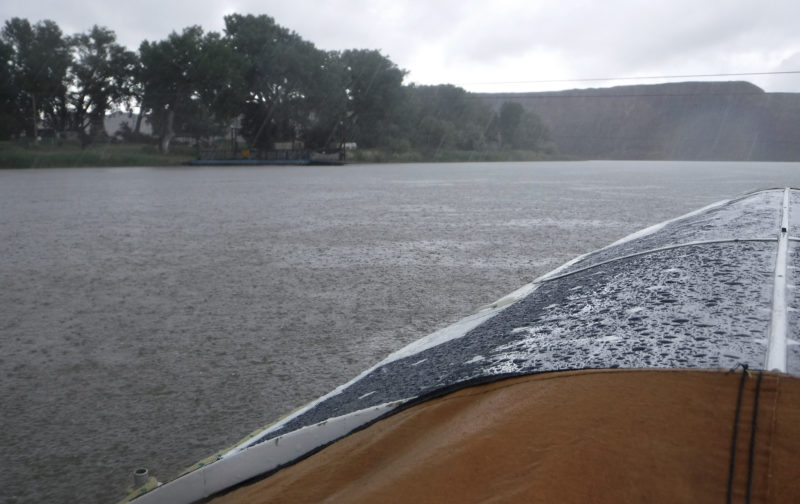

It was also going to be a wet one. Although I have a spray cover for the cockpit and decent waterproof gear, the rain was so heavy and steady that after just an hour I was wet and cold. My feet were still soggy from the launch, and every time I moved new rivulets of water would trickle down my back or neck. Water beaded on the solar panels. There would be no solar power today.

Fortunately, I have a cheap little electric hot-water heater in the boat. It’s so poorly made that I regard it as a fire starter, but it worked this time. Some hot tea and cheese crackers made life a little bit warmer and nicer. My mood was further improved by seeing a flock of great white pelicans, standing motionless, facing upstream, up to their bellies in the water a few yards downstream of a narrow muddy spit of an island stranded in the middle of the river. I wasn’t alone putting up with the rain.

With water above and water below, I cowered under my spray skirt trying to stay dry. I approached the Virgelle Ferry, here idle on the far bank, and passed beneath the overhead cable it travels along, just visible through the rain.

As the dark gray and green landscape flowed by I ducked under the spray skirt. NEWT’s dim interior was infused with an orange light filtering through the wet fabric. Every cubic inch not occupied by me was stuffed with food, water, and gear for a week. A very gentle whirring noise from the stern of the boat was the only indication that the boat was under power. In the turbulent current, a constant tending to the steering lines was required to keep the bow pointing downstream. Two hours of navigating got me to my first stop, Coal Bank Landing, a boat launch and campsite on the north shore of the river.

Steering around the half-submerged bushes straining to keep hold of their roots in the strong current, I made it to the launch area, the bow grating on the gravel boat ramp as NEWT came to rest. The mud squished around my already wet feet as I scrambled out of the boat. The surging river tugged at the boat, scraping it against the bank. The only place to moor was along a marshy, grassy bank adjacent to the boat ramp.

NEWT, buttoned up and protected from the river’s main current, would spend the night at Coal Bank Landing on her own.

The rain continued to drizzle down as I trudged up the gravel path, the sharp stones of the boat launch stinging my bare feet. At the top of the bank there was the new log-built camp station. When I opened the door, a warm dry waft of air wrapped around me, followed by a warm greeting from Casey, the campground host. Casey was tall and thin, with a grizzled face and granny glasses that made him look like an academic. A retired IBM hardware engineer, he was working the summer to get a free park pass for the fall season while staying in the riverside campground.

My five-star accommodation at Coal Bank Landing was a utility room that Casey, the camp steward, let me use for the night. The concrete floor, as hard and as cold as it was, made for a better accommodations than a soggy tent in the rain.

After talking about the rain and the flooding, he rescued me from what seemed to me the inevitable misery of another wet night. I could spend the night in the camp station, and while the hard floor surrounded by tools and supplies for the campground seemed a little industrial and exposed, it was nothing compared to the specter of a soggy night in the boat. I took him up on his offer. After I set my pad and sleeping bag, I crawled in and was lulled to sleep by the sound of a refrigerator rather than the rain on the tent I had been expecting.

After my night in the utility room at Coal Bank Landing I woke up and checked the extent of the rising river’s flooding, as well as the foggy morning I had ahead of me.

On waking the next morning, all I could see through the multi-pane window of the camp station was fog and mist. My little boat was a gray smudge at the bottom of the boat ramp, surrounded by half-downed trees and the gray river fading away toward an unseen far shore.

This was not the weather that had been forecast, but, rain or shine, it was time for breakfast. About three-quarters of the way through my steaming bowl of porridge the sun finally arrived, sending light streaming through the window. Suddenly the sky was bright blue, filled with puffy white clouds, and the water was at least a lighter shade of muddy brown. This was more like it. Time to go.

Casey waved from the shore as I headed out into the strong and swirling current. Motoring downstream, the landscape was looking much less like the flat, bald prairie lands that surround my home. The riverbanks transformed from low, green, and rolling to high, gray, and steep. Bone-white sandstone cliffs, rising straight up from the river, were scarred with meandering, dark rivulets descending into the chocolatey water below. Lone black and ochre granite spires appeared, each pushing up into the now clear deep blue sky. I let the boat drift and slowly spun with the current, providing me with an ever-changing panorama of geography laid bare by time, wind, and water. I was certainly not in Saskatchewan anymore.

Citadel Rock is a granite spire that rises above the softer sandstone that surrounds it. The churning brown water is littered with the debris that the rising river has plucked from its banks.

The current grew stronger as the river narrowed. NEWT, still just drifting with the current, was moving very fast, and I was soon approaching the region where I was hoping to stop for the night. A little bit before reaching the next campground, I noticed a small inlet on the right side of the river, not marked on the map. Some quick thinking and deft motoring got me through the strong current next to the narrow entrance, into a still backwater stream.

Just as I entered, I looked up and saw four deer standing on the bank, only 10′ away and staring down at me. I reached for the camera and, of course, scared them away. Disappointed, I proceeded up the inlet and found some consolation in a narrow stretch of water nestled between a low grassy meadow and steep rocky cliffs. It was so quiet and calm that I was suddenly aware of the low hum of the motor pushing me slowly along the nearby shore.

Tucking into a snug backwater inlet with snacks and a good book was a great way to spend an idle afternoon.

I moored up against the grassy bank and tied lines fore and aft to some half-drowned shrubs. Stepping ashore, I waded through the fresh green grass that poked up through the dusky brown mat of last year’s dried remains. In the distance, old black cottonwoods rose above the peak of the small island between the stream and the river. Across the narrow water was a high and jagged sandstone cliff, studded with protruding boulders and spindly trees clinging to cracks in the rock.

Homemade French bread with canned tuna and mustard was one of my favorite lunches. The scenery certainly helped make the meal fine cuisine.

I decided this would be a nice spot for the night. I had made such good time and arrived quite early in the day—about noon—so I had lunch, and did absolutely nothing for the entire afternoon. I reclined in NEWT, wiggled my feet in the water, and read my book.

When evening approached it was time to transform NEWT into her sleeping mode. Getting the boat ready for night is a bit of a chore. To lie down in the boat, I need to clear a space that is normally occupied by gear. Anything that can go on shore I put there, and everything else gets stuffed under the deck in the bow. I set up the tent (a backpacker’s tent less its floor) over the cockpit with the zippered door facing the shore. If it bodes rain I’ll add the rain fly.

Rain wasn’t threatening so the tent went up without the rainfly. The rock on the opposite bank provided a good way to keep tabs on the river’s water level.

Getting in from shore is kind of like crawling into a small cave and can be difficult if the bank is steep or muddy. Once inside, my head and torso are in the tent portion, and my legs stretch out under the deck into the stern between the batteries. I have pockets lining either side of the boat as a ready place for phones, tablets, chargers, granola bars, and my glasses. This particular evening promised to be dry, so I did not bother with the rain fly and snuggled in for a very quiet and peaceful night.

Across from a primitive but popular campground at Eagle Creek, white cliffs tower over the riverbanks.

I looked out of my tent after waking to find the shore 4′ away, rather than right next to the boat where I’d left it last night. Across the inlet, a rock that had been prominently above the surface last night was now awash. Overnight, the water level had risen about 2′. That was a little alarming. It looked like I was at the mercy of engineers at the dam upstream with their hands on the valve. Luckily, I had tied the boat firmly to trees on shore, so all was well.

After a breakfast cooked on the bank, it was time to go again. As I headed down the river, sometimes under power, sometimes drifting with the current, I came to the start of the continuous wall of sandstone cliffs, with large sculpted features appearing individually along the shore, poking up from dark green shrubbery. One of the most famous is “Hole in the Wall,” a sandstone cliff pierced through just beneath its peak, showing a small prick of light from a long way off.

I pulled ashore at Hole in the Wall, a pierced sandstone cliff set back from the river’s edge. I tried to climb to the cliff, but wasn’t able to scramble up the steep and crumbling slope.

Lewis and Clark, passing upriver here in May 1805, described the scene:

The hills and river cliffs which we passed today exhibit a most romantic appearance. The bluffs of the river rise to the hight of from 2 to 300 feet and in most places nearly perpendicular; they are formed of remarkable white sandstone which is sufficiently soft to give way readily to the impression of water…. The water in the course of time in descending from those hills and plains on either side of the river has trickled down the soft sand cliffs and worn it into a thousand grotesque figures, which with the help of a little imagination and an oblique view at a distance, are made to represent elegant ranges of lofty freestone buildings, having their parapets well stocked with statuary….

Settled comfortably in my boat, drinking tea and eating snacks, I watched the scenery go by. I got better at avoiding the weeds and large debris to keep my propeller clean and running efficiently. The flood was washing the manure left by grazing cattle on the banks down into the river. The ranger at the interpretive center had warned me not to drink or even filter the water for drinking. Looking at the murky brown water, I wasn’t about to try.

In the late afternoon of the third day I arrived at Flat Rock, an undeveloped camp along the south bank lined with a stand of cottonwood trees stretching along the river, many with branches arching out over the water. I’d been warned to avoid the big trees since they often drop dead limbs, so I chose a spot along the riverbank that was not directly underneath any large overhanging branches. Normally, there’s a broad, sandy flat here where it’s easy to beach a boat and camp, but the flooding put it all underwater.

I’m standing on the eponymous flat rock at Flat Rock; it’s normally surrounded by a sandy beach and used as a camping table, but was almost awash in the high water.

I nestled the boat in the inundated grass at the foot of a steep bank, and struggled to step out of the boat, grabbing at the scrub to keep from slipping into the water. I tied the bow and stern lines to trees high on the bank, and the current pressed the boat against the grassy shore. Downstream about 30 yards was a lone, flat rock that gives the place its name. Normally used as a dinner table by boaters, it was nearly awash. Pressed against its upstream side was a tangle of gray driftwood caught in the flood: broken tree trunks, planks, a fencepost, and mud-coated dead reeds. The sun was still high in the cloud-mottled sky and I welcomed the shade of the trees.

About 150 yards across the debris-filled river, tawny cliffs above bands of black and white rock rose high above the water’s edge. On this side of the river, there was little evidence of the camp: a disused fire pit, fallen branches, and overgrown cow paths dotted with manure that wound through the tall cottonwoods.

At Flat Rock, I had NEWT nestled against the shore, and hiding from drifting debris behind a small dam that I built to deflect the larger logs. That didn’t keep me from being rocked by the turbulent current during my stay that night.

Beyond the shade of the trees was a wide dry plain of grass and chest-high sagebrush that extended to the adjacent hills. The land is used by cattle ranchers, and while there once was a fence to keep the cows out of the camp, there’s little left of it now. I packed some water and snacks, then headed out for a hike to gain perspective from higher ground. After an hour of walking over the plain and up a dusty slope, the view was impressive, with the grassy hills and bare cliffs stretching upstream and down, the gray and green plain bordered by the long lush cottonwood grove next to the river.

As I walked back to the boat, a herd of cows with sooty black hides and red and yellow tags in their left ears trotted toward me. They did not seem happy with my presence. Normally, a yell and an arm-wave would scare cattle away, but not these. They continued to advance and I noticed a few of them looked like bulls. I was happy when I regained the cool, dark protection of the cottonwoods in the camp.

After I braved a herd of aggressive cattle, I had an expansive view of the river valley. My campsite is in the center, nestled among the cottonwood trees.

As the sun settled and the shadow of the ridge surrounding the river crept up the cliffs on the opposite bank, I set the tent up over the cockpit and settled in for the night. The turbulence of the flooded river gurgled along the hull and caused a surprising amount of rocking while I was trying to get to sleep. I eventually dozed off, but in the middle of the night I woke up to the sound of wind rushing through the cottonwood trees above. After such a hot day, a rising wind and storm was to be expected.

Poking my head out from the cockpit tent and looking up into the dark, windy night, I assured myself that I was not going to be crushed by a falling branch. The western horizon was blanketed in the black of the storm but the rest of the sky was clear and starry. As my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I could see the cliffs across the water glowing white in the starlight. There was, in spite of the storm, beauty all around me. It was time for some more sleep, so I crawled back into my little tent and listened to the wind with more contentment than concern.

In the morning, NEWT was still in camping mode as I got ready for the final run to the take-out at Judith Landing. The gentle slope of the bank here made it quite easy to get in and out of the boat, so I was able to get away quickly.

I woke to a calm and sunny morning, with the perspective again back to a friendly, bright river scene—the cliffs were the proper tawny gray and the sky was blue. It was a short hop to my final destination at Judith Landing, less than 10 miles downriver. It must have been a slow day at the campground, because both of the rangers there to greet me as I ran the boat ashore for the final time on the Missouri River. I grabbed some lunch and my phone, then trudged up the gravel slope to a picnic table nestled in a grassy spot at the top of the boat launch.

When I got to the end of the trip it occurred to me that I hadn’t taken my red sweater off the entire week. It was time for a shower.

As I sat having lunch and waiting for the shuttle to take me back to my launching point, my phone connected to a Wi-Fi signal emanating from the nearby camp house. It began to beep and boop just like R2-D2 of Star Wars. The isolation had come to an end, the trip was over, and it was time to head home.![]()

Rick Retzlaff is an Engineer, professor, and entrepreneur living (sometimes frustratingly) in the landlocked center of the Canadian prairies. He has owned and sailed many boats, the smallest being NEWT, the largest a Beneteau 40 kept on the Canadian Great Lakes. He has recently left the academic world to develop high-performance solar panels, a pursuit sparked by the success of NEWT. He can be reached at [email protected].

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Rick, I’ve kayaked that stretch of river and it is truly gorgeous and wild. I admire the performance of your NEWT—that turn of speed and efficiency is something I’ve not heard of in a solar boat. Please keep us informed of your further developments in solar marine propulsion!

Thanks, it was a great trip. Especially because of the flooding there was nobody else there. Very lonely. The hull is very easily driven, and I have lots of solar. That’s a good combination.

Rick:

It’s likely that many boaters have been intrigued by your account but few “enjoyed” it. Too many of us have shared your frustration of pushing on when cold and wet, miserable for the foreseeable. Not all voyages are larks.

All of us were surely fascinated by your solar propulsion but you haven’t given us enough description of how your rig handled. Did it perform to your expectations? May we assume that NEWT is a work in progress? Was is possible to clear the propeller from the cockpit? Did your cells and batteries provide more than the boiled water?

We’re all focused on small boats and their performance, yes, but how much did you engineer NEWT for your own comfort? Comfort isn’t dismissible as a design factor. Indeed, it’s a safety issue: miserable skippers make unsound decisions in the moment. I’m assuming that this was a shakedown run, and none of us can predict the weather for time we’ve planned in advance. But we can predict the chance of bad weather and its consequences. If you had foreseen steady cold rain, how would you have engineered your “pilot house?”

Not to diminish your achievements in finishing this float! You adapted and endured. Beside and beyond that, should we consider real comfort as a viable, important design factor in small boats? Might we agree that dry, warm and well-protected skippers are less distracted? This isn’t about you, Rick, but about a kind of tough-guy, I-can-take-it, Spartan ethic of small-boat design. Truth to tell, I don’t admire the Spartans.

Your use of the wand-rigged camping tent over your cockpit was apt. Those wands have been ingeniously used as design components for decades. Would you have been more comfortable and would you have enjoyed the fascinating banks of the Missouri more beneath a wand-curved light bimini? I’ve honestly enjoyed rainstorms sitting dry beneath the bimini of a bigger boat. That our boats are small doesn’t demand discomfort. Might we encourage small boat design that ensures a dry, rain- and sun-shielded conning seat? Or are small boats only for Spartans?

Adkins

Thanks for the insights. Yes, comfort is an issue. This was certainly not optimized for comfort. I’m thinking maybe a larger version of this is in order. I’ve had this out for two seasons. Last year I spent a month on Puget Sound. A lot more ambitious trip, much more urban and open. Less lonely. I did have a small tarp that I would place over the tent structure for sunny afternoons. That worked well. The solar panels provided all of the power. For propulsion, cooking, lights and charging devices. I’m busy developing a commercial version of the solar panels used here. Optimized for high performance lightweight applications like this. You can track this at http://www.lightleafsolar.com.

The Angus Rowboats RowCruiser might be a better starting point for a solar expedition boat. Cabin/sleeping accommodations is built into the forward section of the hull – no tenting required. There is plenty of deck space for solar panels, and enough transom to permit mounting an electric trolling motor, plus you have sliding seat rowing as alternative propulsion, and a way to get some exercise on a longer trip.

Yes, I’ve identified this as maybe the next version. I’ve been talking to Colin about this, but he is currently busy with his antonymous boats right now. The Angus boat is slightly larger, slightly bigger on the beam, lots of room for solar panels. I’ve been thinking of producing a solar conversion kit for this type of boat. I think there are a lot of folks like me, a bit older and not thrilled about rowing six hours a day. But still needing to get out there and adventure.

Hey Rick, very cool! It sounds like it was quite an adventure. What a neat little boat. I have a small solar-powered boat too. It has a 2-stage variable-speed engine that relies on dispersed soil-based chlorophyll inverters that transform sunlight to chemical energy, then I supply mitochondria to convert stored carbohydrates into paddle strokes.

Good morning Cathy. It’s good to hear from you. I just had lunch with Gord the other day. Big changes coming in their life in the next year or so. Yes, I used to have a system like that, but it is getting older and not working as efficiently. Also, it’s tough to paddle while you’re eating cheeses and drinking tea. When it comes right down to it, I’m just a lazy bum. I spent a month in the boat last year in Puget Sound. I remember passing a group of kayakers (I go slightly faster than the typical kayaker paddles). I waved as I went by. Feeling kinda guilty. You folks still getting out and paddling much these days? I’ve taken a leave of absence from the University and I’m developing a new kind of solar panel that is really good for these high performance lightweight applications.

Harassed by a band of wayward marauding cows! Who knew? Great story. Thank you.

Brad, I just took a look at this article and noticed some comments. Thanks for the compliment.

This summer, I’m planning on building a solar-powered bike camper and hitting through the mountains.

Rick,

That’s really a nice boat.

Twenty five years ago my family and another family floated in five rented canoes from Ft. Benton to the James Kipp area where US highway 191 crosses the river just above the Fort Peck reservoir, about three days on beyond Judith Landing. Your pictures brought back great memories.

During the seven days, we saw only one other canoe (briefly, taking out at Coal Banks as we went by), two cowboys riding along the river, and a B-1 bomber that flew low over us at dusk one evening, with afterburners on. Really loud. Scared us to death, because you couldn’t hear it coming. Not another soul. Almost no cattle. No dirt roads or even Jeep tracks along the river, and no campgrounds except at Judith Landing. Ancient tepee rings and wild horses up on the bluffs in several places. From your pictures and descriptions, it looks a little more “built up” today, though obviously still pretty wild. We rarely paddled except to go ashore to fix lunch and to spend the night. Sleeping and eating ashore was comfortable, but you did have to check for rattlesnakes.

I’ve built several canoes and kayaks, and understand the desire to use what you’ve built. But for us, the rented canoes and sleeping comfortably ashore were fine.

I hope you continue to work on the solar power as batteries become cheaper with more capacity. Freeing up some deck space and interior volume sounds like it would be very helpful.

Rich Wagner

Rich, I just took a look at this article and noticed some comments. Thanks for the compliment.

Very well written adventure story, Rick. Fantastic descriptives.

I see your business is selling the solar panels. I would really like to read an Instructable on the ‘motorboat’ conversion process.