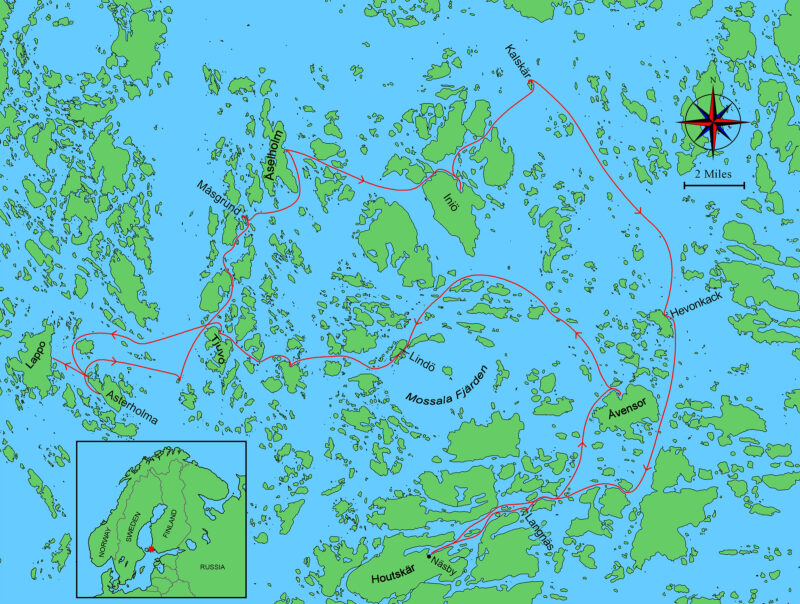

On the west coast of Asterholma, a 1 1⁄2-mile-long island in Finland’s Åland archipelago, my wife Marlen and I loaded our boxes, waterproof bags, camping stove, and tent aboard STRYNØ, our 20′ 8″ traditionally built sail-and-oar double-ender. At the water’s edge a boathouse with walls painted barn red was surrounded by reeds, but much of the island’s shore was rock in striations of pale gray and beige left bare, smooth, and undulating by the retreat of the last ice age. With our gear loaded, we pushed off, stepped aboard, and set the two rectangular spritsails. STRYNØ coasted out of the slick in the lee of the island and drifted into a wind that just dimpled the surface of the Baltic Sea. Glittering ripples soon surrounded our downwind course, gurgling as the bow passed through them.

Photographs by the author except as noted

Photographs by the author except as notedThanks to her light weight and shallow draft, STRYNØ can be launched and recovered just about anywhere. At Asterholma we found a shallow spot by a boathouse and slipped STRYNØ off the trailer straight into a soft cushion of reeds.

It was August, and under a brilliant blue sky we were off to explore the islands of Åland, the autonomous region at the southernmost tip of Finland where Swedish is the official language. Of the more than 6,500 islands, only about 60 are inhabited. The larger islands rise as high as 100′ and are mottled in green, gray, and gold in a patchwork of dense woods, bare bedrock, and summer-dried grass; many of the rest are little more than low, nearly flat spans of rock with almost no vegetation.

As we were enveloped by the extraordinary quiet of the archipelago on a warm summer day, Marlen and I made ourselves comfortable aboard STRYNØ.

Christoph Busse

Christoph BusseThe rig of the tosmakke offers exceptional versatility in a wide range of wind strengths. In lighter winds the topsail and jib can be set, but as the wind increases these can be taken down and then the main and foresail can be reefed in turn to balance the sail area. Beyond STRYNØ in this picture can be seen LENE, a tresmakke from the Roskilde Viking Ship Museum. LENE’s hull shape is very similar to STRYNØ’s and her sailplan is similar with the obvious exception of the third mast.

I had built the boat from plans for a Tosmakke, a traditional Danish working boat. To is two in Danish—for the two sails—and smakke is the sound a spritsail makes in a jibe. These boats were traditionally built for hunting porpoises in summertime and dragging nets for fishing eel in wintertime.

We soon left the marked waterway to set off between islands 2 miles (all nautical in this story) away to follow another of the many marked waterways through channels as wide as 200 yards, as narrow as 50 yards. We had sailed about 9 miles by 6 p.m. when we landed on Måsgrund, an island just 200 yards long and 50 yards wide, with a weathered rounded summit that rose only as high as our masts. We eased the boat alongside a granite ledge that loomed above a fathom of sapphire-blue water. Hungry and tired, we offloaded our cooking gear and stepped ashore.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

Close by we found a spot to sit and lean back against the smooth granite, still warm from the day’s sunlight. Soon, we were lying down and stretching, luxuriating and unwinding our limbs after the long day of sitting in our small boat. We dined on a salad of beetroot, onion, avocado, and goat cheese dressed with balsamic vinegar and olive oil, seasoned with fresh-milled pepper, and accompanied by some Swedish surdegs knäcke —a crispbread—with extra-salted butter.

Our first evening in the archipelago was typical—sunlit until well after 10 p.m., still, and silent. We tucked STRYNØ into an opening in the granite and settled in for the night on Måsgrund.

Afterwards, I set off to explore the island. I walked barefoot on smooth, warm rock slabs, and after the constant movement of the boat it felt good to stand on the unmoving ground. As I stepped away from the shore, the smell of seawater came with me on the light evening breeze but was soon replaced by the fresh scent of pine and juniper. The pine needles shivered in the wind. The rocks were overgrown by lichen and moss, in places dry and crisp beneath my feet, in others so soft that I sank up to my ankles, and everywhere ants had cut trails through the vegetation like miniature roads in a lichen forest. Near the center of the island the trees grew close together, and their branches cracked and broke as I made my way through; the sharp juniper needles bit at my hands and poked through my pants.

To the west of the island there was a 700-yard span of open water between a neighboring forested island where summer house was hiding between the trees. At the opposite shoreline reeds grew straight and tall—more like the shore of a lake than the Baltic Sea. In the quiet evening an oystercatcher was looking for food and a flock of swans had come ashore to sit at the rocks for a while. Arctic terns swooped and dove for fish and occasionally got into noisy fights. I heard the raucous cawing of ravens in the distance. Of course, there was the perfect spot for mooring the boat. I found a bay that was no more than a crack between rocks with deep water and just long and wide enough to enclose our boat, protected from the wind from three directions.

As I made my way back across the island, I found a 20″-long osprey feather lying on the moss and picked it up to bring to Marlen. I roused her from her repose on the rocks and together we rowed to the new mooring site. With STRYNØ secured, we went ashore, cleared the ground of pinecones and branches beneath a large pine tree, and pitched our tent on a soft bed of needles.

At Åselholm we came alongside the ferry dock and moored up for the night. After we had tidied up the boat, we walked across the island to fill our water bottles. We spent the night here under the tarpaulin cockpit tent.

After breakfast and a swim in the cold clear water we broke camp and sailed a few hours with the dying wind headed for Åselholm. We cruised slowly in the warm sunlight around the south end of the island with jib and topsail set. After covering 5 miles, we moored by a concrete pier for the ferry at the foot of an uneven wooden bridge with moss growing out of cracks in the planks.

We went ashore and the ½-mile walk along an ochre dirt road took us across the island, past fields, grassland, wild gardens, roadside flowers, and wild strawberries. We turned down the driveway of a lot that had several barns, a harbor with two piers, each with a wooden boathouse, and two windmills. We rang the doorbell at the two-story house to ask for water and met Jimmi. He filled our bottles and offered to show us his windmills.

The nearest of the two mills, a corn mill more than 200 years old, was about 15′ high and had the proportions of an outhouse with a steep-pitched roof. It stood on a platform of rough-hewn logs weighed down by lichen speckled stone slabs. The space inside was so tiny that we could only step one by one into the darkness. Flour dust on the floor rose from our footsteps and glowed in beams of light that filtered through the gaps in the wood.

We explored Åselholm’s two windmills. The larger of the two (seen in the distance) is unusual: Most Scandinavian windmills have four vanes rather than six and even rarer still, here the vanes power a sawmill housed within the round tower.

The second mill was much larger, round and shingled, and had six sails instead of the more usual four. Inside was a vertical sawmill with six blades driven by an overhead iron crankshaft. “Everything is there and it’s all working,” Jimmi told us, “but no one really knows how to operate it.”

We returned to STRYNØ and enjoyed dinner while sitting on the wooden pier next to the boat. To get ready for bed, everything in the area between the masts—cooler, camp stove, and tools in wooden boxes and the thwart for the forward rowing station—had to be moved to make space for sleeping on the floorboards either side of the daggerboard. After we set up the tarpaulin that covers the forward half of the boat, we had a dark, tiny, crowded but well protected and cozy space for two. We spent a calm night and slept soundly.

Early the next morning, to our surprise, the ferry came to the otherwise empty pier bringing a truck to collect trash. Two workers cleaned the corner of the pier nearest us twice, sweeping away gravel and dust just to take a closer look at our boat. We were still in our sleeping bags.

Soon after breakfast we sailed into a warm and sunny day heading 6 miles to the eastward to Iniö, one of the few places we could buy food. Just past noon the wind rose to 10 knots from the northwest, so we had easy sailing on our eastern course with jib and topsail added to the rig.

The opening to the harbor on the northeast coast of Iniö is protected by three wooded islets, and the marina, 1⁄4 mile in, is set among lush reeds 6′ tall. After shopping in the general store, we left to sail 3 ½ miles to Kalskär, one of the thousands of Åland’s uninhabited islands. It has a small bay open to the southeast on one side of an isthmus that connects the 400-yard-long main body of the island to its smaller sister, and another even smaller bay open to the northwest. The weather forecast promised a change of wind blowing from the south that night, so we chose the northern bay. The 13-knot wind blew right into the bay, so I took down all sails and let STRYNØ coast, carefully watching the stony ground and underwater rocks until the anchor found a hold in the rocky crystal-clear shallow water. The rode tightened and I made it fast to the sternpost.

We had to wait a long time each day to see the sun set. Here at Kalskär, it was just 30 minutes to midnight when the sun finally dipped below the horizon. It would stay hidden from view for just two and a half hours.

An evening walk along the steep west side of the island took us past pools of water trapped in fissured rock and rocky bars dotted with lichens and strewn with bleached skulls and skeletons from small mammals and seabirds, leftovers from ospreys that bring their prey to the pine trees at the top of granite banks. The wind fell asleep, the waves calmed, and the reflection of the sky lay over the rocky seabed under the still water’s surface. In the evening, after a refreshing cold bath, we had a fire in our wood-burning camp stove to warm ourselves, and with the last red beams of the sunlight illuminating our chart we decided we would turn south tomorrow for Näsby.

After breaking camp and teetering across slippery, algae-covered stones to load the boat, we set sail in light rain. Dull white clouds in front of a gray sky promised more rain to come. We worked STRYNØ, with topsail and jib added, against a 6-knot southeasterly wind that misted our faces with gray raindrops from clouds that left only a few blue gaps in the sky. Marlen was at the helm while I trimmed the sails, both of us enjoying sailing with the rising wind.

The sky cleared and the sunlight had brightened the islands around us for only 15 minutes before I decided to take down the topsail. “Why are you taking it down?” Marlen asked, still pushing STYRNØ at speed in waves now showing a bit of white at their crests. Only a few minutes later I hurriedly took down the jib. Soon we were flying with both spritsails heading hard against the wind, on the verge of reefing, picking our course between buoys, rock outcroppings, and islands. Steepening waves shook our boat and soon it was rolling like a rocking horse in cross seas. Suddenly, the wind blew away all the clouds and dropped as abruptly as it had built. Choppy waves in mixed directions brought the boat to a full stop. After a moment of confusion about what to do I set the jib again and the boat, still bouncing, started slowly moving through the waves.

At Hevonkack we found the only sand beach of our entire trip. We still moored STYRNØ with a beach rock and a stern anchor and enjoyed wading in and out for a swim rather than having to climb rocks to get out of the water.

We spotted an area of smoother water and as soon as we reached it, we began sailing normally, heading a last ½ mile to an exceptionally rare place in the rocky archipelago: a beach. The 50-yard-long crescent of caramel-colored sand on the lee side of Hevonkack was a very welcome place to bring the boat ashore. Some boulders, covering an area about the size of a small house’s footprint, rose only inches above the water and protected the shallow sandy bay. Marlen and I found a dry, sun-warmed place just wide enough for the two of us to sit with a view over the surrounding islands in the calming, sunny evening.

After breakfast and gathering blueberries, we left the wind-protected beach and sailed directly into a 15-knot southerly. Sailing toward Näsby meant tacking roughly 3 miles before holding a starboard tack to make a 7-mile passage along a natural channel formed by a gently meandering string of gaps between islands and rocks. The wind-scuffed waves slapped the bow and burst into white spray. As the wind strengthened to 20 knots Marlen and I had to move fast as we dove under the spritsails with each tack, holding our seat cushions tight lest they be blown away. The boat was making great speed but it was challenging to beat to windward, coming about every 500 to 1,200 yards, often between the foot of steep rock faces on one side and rocky shallows striped with white foam on the other.

At 5 p.m. we veered west and hoped to bear away on a steadier point of sail, but in the lee of a tall, forested island we could only try to sail puffs coming from changing directions. I relieved Marlen at the helm and helped to prepare some cheese bread. We had been too busy in the wind to feel our hunger and exhaustion. Dinner boosted our mood. We landed at Langnäs, an uninhabited islet composed of a trio of ridges connected side by side. We were still tired and hungry and had to have a second dinner—noodles and pesto—to restore our energy before we could set up our tent.

It was already afternoon by the time we left Langnäs headed for Näsby, the main village on the island of Houtskär. The weather forecast we heard before leaving concerned us; we had to look for a good shelter for a storm that would arrive that night and Näsby’s harbor is safely nestled among the peninsulas on the east end of the island. Set on pilings over the water at the bouldered shore were plain buildings with small four-paned square windows and vertical siding, some unpainted and weathered slate gray, some bright barn red, and others once red, turning gray. The building above the gas dock was built of logs, lapped at the corners, flattened on their sides and deeply checked with age. The buildings along the shore were backed with a thicket of trees in full leaf. Behind them were slender evergreens only slightly taller than a shingled church spire rising in their midst.

Marlen was at the helm as we approached a 100-yard-long pier and headed for the sole open mooring space among all the huge motorboats and even larger sailboats moored there. We were both nervous. We had no motor and there was too little space between the boats to row in among them against the wind. I prepared the lines, one at the stern, one at the bow, and lowered the jib, but still we were speeding along parallel to the pier heading for the empty slot. From the stern of every boat, people looked on as the strange little two-masted sailboat flew by. I set our two small fenders, let fly the foresail, and got ready to fend off as Marlen released the mainsheet and rounded up into the mooring space, as neatly as if she’d just taken a master class.

The two motorboats alongside us were twice as long as STRYNØ and there was barely room to squeeze the fenders between the boats, but we had made it. We breathed deep and set about tidying up. We left the boat to walk into town.

When we returned, we found a powerboat twice the size of our tosmakke had squeezed into our spot, pushing STRYNØ forward under the bow of two boats, nearly flattening all the fenders that separated our boat from them. The harbormaster, seeing our precarious situation, took pity on us: she had a liking for wooden boats and allowed us to move to a daytime-only mooring at the innermost end of the pier inside the harbor. We had a safe spot for the night.

The following day, many of the people walking about in the crowded harbor were interested in STRYNØ and stopped to ask questions about her and our cruise. We spent the time relaxing under the tarpaulin, walking into town to shop for food, and visiting historical houses and the church. Having spent one night and the day in the hustle and bustle of Näsby, we decided to slip away. We rolled up the tarp, maneuvered away from the pier, and set sail in a 10- to 15-knot breeze. It was 6:20 p.m. and our destination, Åvensor, was 6 miles away.

Marlen was happy to be at the helm once more and sailing smoothly downwind. In the warm evening, the sun came out and lit up our sails. I set the topsail and the jib. Reflected sunlight from the bow wave played upon the jib. Its concave curve gathered and amplified the sound of the bow cutting through the water, making it audible enough to be heard at the helm. The sound brought a smile to Marlen’s face. For an hour and a half, we flew across a glittering golden sea into the openness of the archipelago.

We went ashore at Åvensor to find the best campsite and left STRYNØ, her sails up, temporarily moored while we explored. Sometimes we were lucky and found a good place to pitch the tent nearby, other times we’d have to sail or row farther around the island. In the distance, to the right of this picture, can be seen one of the limestone kilns for which the area was once famous.

At Åvensor there are two 125-year-old quarries that were created to mine limestone for making cement. At the north end of the island, a natural bay 500 yards wide and about as long ends in marsh overgrown by reeds. It has a broken-down pier once used by ships taking the cement from the island to ports in Finland and Sweden between 1900 and the late 1950s. We tied up at the innermost end of the pier almost in the reeds and walked just 50 yards inland along a path that once was a road to the first quarry.

The water that had flooded the quarry was crystal clear and darkened from blue-green into black where the bottom is more than 100′ deep. Vertical walls 30′ to 60′ high surrounded the quarry. High above, surrounded by a new-growth forest of spindly trees and almost in ruins, were the lime kilns that looked like squat brick lighthouses. We clambered over the rocks and above the quarry to see the sunset and the waterway through which we had sailed. As we stood in the evening breeze with the low sun in front of us, a lone sailboat was winding its way through the archipelago of forested islands, rocks, and stony reefs.

Despite the fading daylight we wanted to swim in the still water of the quarry. We waded through the shallow water. In the darkness we could make out black finger-sized crayfish crawling across the stones at our feet.

We took a morning walk through the reeds to another of the island’s quarries, then loaded and launched STRYNØ. With her full foresail and reefed mainsail set, the gusting southwesterly pushed us on our northern course, speeding as fast as the foam-crested following seas. Behind us our wake lingered white across the waves. The forecast was for winds of 15 to 20 knots for the day. We had decided to set sail only after a lengthy discussion about if we should go and if we did, where we should go. Now, as we sped through the water for Lindö, we were a little tense but still confident in our decision.

For STRYNØ, a 23-knot wind is the upper limit. She is an open boat and at speed short, steep waves wash over the bow. One person must stay at the helm, leaving the other to manage the sails and lines. The weight of the crew in the boat is important for its balance—a sudden strong gust, and the crew must move swiftly to windward; in an unexpected lull they must shift to the center; moving too far to leeward can cause the gunwale to dip.

As we sailed on, the southwesterly steadily rose, visibly bending the unstayed masts. We left the protection of the leeward islands that kept away higher waves, and suddenly there were almost 2 miles of open water that we had to cross and the sea was becoming disturbed. Steep, dark gray waves broke over the port gunwale from bow to stern. STRYNØ was so steeply heeled that it was hard to find a suitable spot to sit. I spilled the wind in the foresail, holding it in just enough to stop it from luffing, and Marlen held both the mainsheet and the tiller tight. The boat leapt like a porpoise from wave to wave as the wind brought us ever closer to the rocky shore of one of the islands scattered along our route. We would have to come about to avoid it.

“Tack when the waves aren’t so high!” I shouted to Marlen. She waited for the right moment while I prepared myself with an oar to help with coming about. When Marlen pushed the tiller leeward, STRYNØ needed no assistance—she turned with ease and settled on her new course.

Gusts laid white stripes across the dark sea, and all around us the waves were cresting. After sailing free of the rocks, we turned again and held on, heading for the lee of Biskopsö. We made it to the northern side of the 1⁄2-mile-long island, and in the lee of its wooded hillside I dropped the sails. Marlen and I stretched out on the smooth granite, exhausted by the first 5 intense miles of the day. I quickly fell asleep. When I woke, the sky was darker, and the telltale ash-gray streaks beneath the clouds indicated showers were coming our way We decided to press on. If we kept to leeward of the island chain to the northwest, we would have milder wind and smoother seas.

As we plowed on, the clouds flung heavy raindrops that pelted us and soon soaked us through to the bone. As evening drew near the wind shifted and we were able to shake out the reefs and set full sail as the wind came around to our beam. The backside of the storm brought clear weather, and we made landfall on the south shore of Lindö island in the evening light.

Lindö is located on the northwest quadrant of Mossala Fjärden, a circular body of water about 3 miles in diameter, encompassed by a fragmented perimeter of islands, many of them curved around a common distant center. I had been looking forward to visiting this landscape of concentric circles of rocky islands that show so clearly on the charts. The islands are the remains of a magma intrusion that penetrated the Earth’s crust over a billion years ago. Standing on Lindö we could clearly see the round shape of this distinctive bay.

Throughout the trip we used the portable camp stove rather than make fires on the granite. The intense heat from a direct fire can cause the rock to break, sending out an explosion of hot embers and rock fragments.

That evening the wind fell from the stormy afternoon to a gentle whisper through the pine needles, to absolute silence. With the weather now again calm, the sky turned blue, and the sunset was seemingly endless, stretching from about 8 p.m. to 11 p.m. But even when the sun had finally slipped below the horizon, it was never truly dark, and even though there were no clouds it wasn’t dark enough to see the stars in the 2 1⁄2 hours that the sun was below the horizon.

The boat was safe at anchor, and we had the island to ourselves. The rhythmless burble of the ripples against the ledges and boulders faded to near silence and then all movement and sound stopped. As we lay in our tent surrounded by stillness, I heard only the beats of my pulse and the ebb and whisper of my breath.

We decided to sail westward to return to Asterholma. We had three days to get to the ferry at the neighboring island, Lappö, and to roll aboard with our boat. The weather forecast promised winds from the southwest, sunshine, and a chance of showers.

The islands surrounding Mossala have smooth but steep sides of polished rock, and those facing Lindö form a kind of channel 100 yards wide. A series of short tacks in the channel brought us to a wider area and our course turned more to northwest. The wind rose, and I took down the jib. We could sail with the two spritsails speeding STRYNØ along while Marlen and I sat comfortably in the cozy niches between boxes with drybags as our seat cushions.

The towering cumulus clouds pushed from the southwest across the luminous blue sky slowly turned from white to gray and soon changed shape into a large, dark anvil. As the wind picked up, we searched for the entrance to a marked waterway that would lead us in short, winding turns through the chaos of rocks and islets. Both of us shifted to the windward gunwale to balance the boat as we rushed past a white pile of stones, the mark we had been looking for. We needed to tack and had only four boat lengths to the next mark. The waterway markers—red and green sticks stacked on rocks or sunken boulders—took us through three 90-degree turns within 300 yards. With two more quick tacks and a jibe we threaded through the narrow section, leaving a foaming white wake that disappeared behind a veil of rain under another dark cloud. The wind died down a little as we tacked into another narrow passage and sailed another mile, slipping around the dark clouds and into bright sunlight with veils of rain on both sides of us.

Most evenings, the wind would die away and the clouds, if there’d been any, would also have retreated. The smooth granite rocks, like those here at Tjuvö, did not always offer useful cracks for mooring lines so, to hold STRYNØ perpendicular to the shoreline, we would set a stern anchor and wrap her painter around a loose rock we would find nearby.

With the wind continuing to die down, we turned northwest and made landfall on the north end of Tjuvö. The island offered a good anchorage in 6′ of water, and granite ledges just 1′ above water level formed a kind of natural pier 50 yards long. We pitched our tent on another bare ledge just in front of a forest. That night I woke from a heavy downpour pounding the rain fly, but soon felt asleep again.

As we sailed away from Tjovö, wisps of clouds over curved curtains of rain preceded a gray monster that was slowly drifting toward us. We knew there was wind over the blackened water in the distance. We prepared for wind and rain by packing away all loose stuff, taking down the jib, and wrapping ourselves in the tarpaulin. Marlen hid under it with the foresail sheet and I was at the helm with only my head sticking out. We were just 1 mile from the northern end of Asterholma when we were overtaken by a heavy shower that reduced visibility to 100 yards. Cold drops hit the tarpaulin with heavy impacts, bursting into spray. The sea was smooth and black under a pearly shimmer of bursting drops. Trickles of water ran through my woolen hat into my eyes and down my neck. The wind picked up and I had to change my ice-cold hand at the tiller from time to time.

On the last day of our trip, we sailed through a heavy shower. But in the calm of the evening, while Marlen prepared dinner, we raised STRYNØ’s sails so they could dry in the sun. The island, Asterholma, is named for the asters that bloom in the rock pools along the shoreline.

The cloudburst did not last long and as visibility improved, we felt it would soon be over. But as we approached our anchorage, I had to take down all the sails in the rain and got entirely wet. We needed to drift with the wind as slowly as possible into the shallow bay, which was littered with rocks just beneath the surface. The rain finally stopped. We pulled the rudder off, lifted the daggerboard, and rowed into the bay. Marlen stood at the bow calling out shallows and stones while I maneuvered the boat in the just-deep-enough water. When we reached shore, it was hard to find a level space for the tent. We fought our way through juniper thickets and had to settle for uneven ground.

We rose at 7 and on a calm sunlit morning set out for Lappo. Arctic terns flew tight circles and dove to catch small fish. After rowing out of the bay at Asterholma, I set the jib and topsail. STRYNØ glided last 2 miles of our trip through a glittering silvery blue sea. Marlen and I sat smiling, listening to the sound of the water tumbling at her bow. We never grew tired of it.![]()

Sailing the Baltic Sea became a dream for Sebastian Schröder while kayaking around the Danish island of Bornholm in 1996. Since then, coastal cruising in small, open, traditional wooden boats has become a passion. Living close to Leipzig in the southeast of Germany, he frequently sails the nearby region of Neuseenland where old open-pit coal mines have been flooded to create new lakes. His work as a live illustrator in creativity workshops and conferences gives him the opportunity to sail and kayak the Baltic Sea and to build wooden boats in traditional Scandinavian style as Feinspiel.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

A beautiful boat and great open-boat sailing story in Baltic Sea changing weather conditions. Did you derive STRYNØ design from one of the three Smakkejollen described in Christian Nielsen’s Wooden Boat Designs: Classic Danish Boats measured and described – or is she based on another plan?

Hi Pascal,

There was an original boat built by Mads Illum Petersen, owner of the boatyard in Middelfart (Denmark) from 1855-1907. This boat is now stored at the Fishing and Maritime Museum at Esbjerg and was measured for building a replica. A friend of mine was involved in the boatbuilding process and I got a printout of the basic measurements. Together with him I could sail the replica in Middelfart and have a closer look at the sails and lines and the characteristics of the boat. I took all that as a starting point to develop a digital lapstrake plywood design with seven instead of nine planks and a daggerboard. The result is STRYNÖ. I know the book of Christian Nielsen, but unfortunately only my brother owns one, so at the moment I am not sure which design out of the book would be closest to what I built.