In Cleveland, Ohio, Henry Billingsley was thinking about retirement. He had been practicing law for decades and was ready for the next chapter in his life. While he had no great plan set out, he knew that he wanted rowing to be part of his future. In the 1970s, he had trained as a sweep oarsman at Columbia University, rowing starboard. He continued the sport long after graduating, but in the late 1980s took a class at the Craftsbury Sculling School in Vermont and became a devotee of single sculling. Now, as he approached his seventies, he knew it was time to replace his flatwater racing shell with a more seaworthy and forgiving craft.

He had always wanted to build and row a Whitehall, attracted to the boat’s history as well as its proven performance and classic lines. But there were two problems. First, traditional Whitehalls had fixed thwarts, and Henry wanted a sliding seat. “The fixed thwart,” he says, “deprives the rower of the use of the largest and most powerful muscles in the body—the legs.”

The second, and potentially greater, problem was that Henry knew “nothing about building boats.” He was, he thought, a “reasonably competent shoreside carpenter,” but he would have to leave the world of “square and straight” and enter the world of “beveled and curved.”

Photographs by Ed Neal

Photographs by Ed NealThe first 18 western red cedar strips were installed working up from the sheer. Then the strips were laid working down from the keel, and the shutter strip (which closed up the hull) was installed along the chine.

Not to be daunted, he continued to research the Whitehall type and came across J.D. Brown’s 1985 book, Rip, Strip, and Row, in which he found plans for John Harstock’s modern version of the classic skiff: the Cosine Wherry, a 14′2″ × 4′4″ strip-planked rowboat for one or two rowers. Here, says Henry, was a “lightweight, beautiful boat complete with excellent guidance on how to build the hull. But there was nothing about creating a sliding-seat system.” There were suggestions for sliding-seat mechanisms that could be dropped into the hull, but to Henry’s eye they spoiled the boat’s clean lines and took up too much space; he wanted to build his sliding-seat mechanism into the hull from the outset. It was time for some help. It was time to talk to Ed Neal.

Ed Neal learned to build boats at the Cleveland Public Library. In the late 1990s he had returned from a canoeing trip in Canada wanting to build an outrigger to make his canoe safer when paddling on remote lakes. The library had an extensive collection of boatbuilding books and, he says, “I fell down the boatbuilding hole and have yet to emerge.” It was no surprise: Ed had been an avid woodworker since his Boy Scout days and had been reading WoodenBoat since the 1970s. He continued paddling, but when WoodenBoat published a three-part construction guide by John Brooks on how to build his 12′ Ellen design, Ed was smitten. He followed the step-by-step guide and built a 2′ model. “I learned so much from that, and gained the confidence to build the full-sized version,” he says. Twenty-five years later, “I still use techniques picked up from those articles.”

Indeed, for Ed the 2′ Ellen model was the modest beginning of a now decades-long passion. Since 2000 he has built two kayaks and an 18’ Firefly performance rowing boat, and has led classes in building the Mike O’Brien-designed 15′ Six-Hour Canoe and two Ross Lillistone–designed 15′ Fleets.

Once the hull was removed from the molds and turned right-side up, cleanup work could begin on the interior: first the excess glue was scraped away, then the sanding would follow.

Ed was leading the Cleveland Amateur Boating and Boatbuilders Society (CABBS) Boatbuilding Basics Workshop in 2019 when he met Henry. The two had briefly crossed paths when volunteering at a Cleveland public school, but otherwise did not know each other until Henry asked Ed about his Cosine Wherry sliding-seat issues and they agreed to meet. As the conversation progressed, Ed recalls, they discovered they had both attended college in New York City and had both covered their living expenses by driving a cab. They bonded immediately. Ed agreed to help Henry with his project.

The arrangement worked well. “I could not have hoped for a better teacher, guide, and friend than Ed,” says Henry. “Calm, confident, precise, and infinitely patient, he walked me through the process.” Together, they laid out the molds and constructed the strongback. The transom was fashioned in solid sapele, and the hull was strip-planked in bead-and-cove western red cedar, which they milled and scarfed from 2×4s. The fully planked hull was sheathed inside and out with epoxy-saturated fiberglass. Sapele gunwales were fitted to support the heavy cast-bronze outriggers. Throughout, Henry and Ed worked in partnership. Henry put his woodworking skills to good use and Ed acted as teacher, explaining boatbuilding techniques and then putting the tools in Henry’s hands so he could do the work.

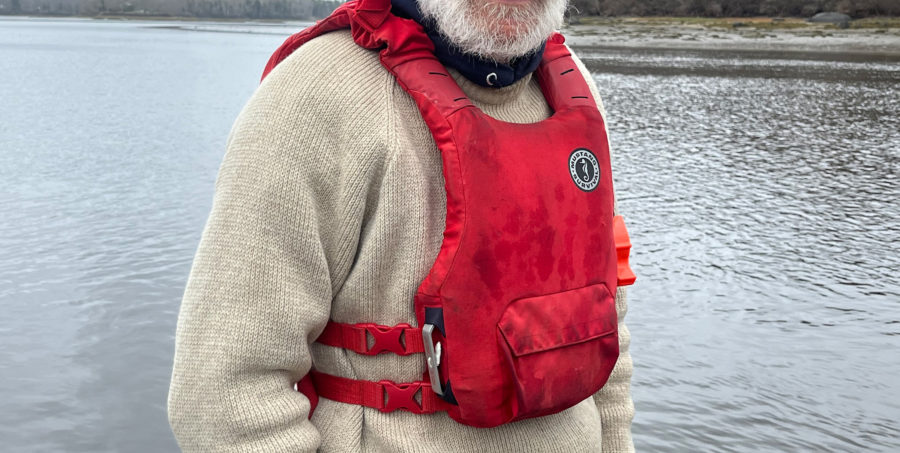

To support the rails for the sliding seat, and to add flotation, Henry Billingsley (seen here) and Ed Neal framed-in plywood storage “tanks” on either side, with watertight hatches. The tanks were coated with epoxy and then painted the same color as the rest of the interior so that, visually, they almost disappeared.

Aside from an unexpected hiatus of several months when Henry broke his arm, the project went smoothly, but when it came time to construct the sliding-seat rig, both men were challenged. They spent hours examining sculls—measuring seat height, oarlock height and span, and foot stretcher distance and angle. They decided to make the seat adjustable to accommodate scullers of different heights.

Both had sliding-seat frames that they scrutinized. Ed had a Piantedosi frame and Henry had an Oarmaster frame set to a position he liked in his own rowing shell. They pulled it out, temporarily installed it in the Cosine Wherry, and took it down to the lake. “Henry rowed,” says Ed, “and we moved the frame to different locations along the keel to find the best balance point for solo rowing and the appropriate place for the oarlocks.”

Tom Baugher

Tom BaugherEd and Henry outside the workspace where they built TAMO.

They designed a pair of tanks with parallel inboard sides that would support the sliding-seat rails, but identifying the right materials for the wheels and rails involved much trial and error. “We progressed very slowly,” said Ed, “like blind men feeling our way along a wall.” When they got stuck searching for a solution, Ed would, says Henry, “calmly suggest that we just sleep on it. Being old guys, we would routinely wake up in the middle of the night and then suddenly get a flash of insight. Some of our best problem-solving came that way, and it gave rise to the genesis of the boat’s name: TAMO, for Three A.M. Oracle.”

At last, there came a breakthrough. Fellow CABBS member, Jim Batteiger, a retired master elevator mechanic, passed along some salvaged, 2″-diameter stainless-steel wheels with grooved circumferences that perfectly fit over 1⁄2″ heavy-duty copper pipe. “We designed a seat carriage around those wheels,” says Ed, “and used the pipe to create long rails that could accommodate either solo rowing or rowing with a passenger.”

On launching day, Henry gets to use the sliding seat for the first time.

As construction neared completion Ed went to visit his son and family in Seattle. One morning, shortly after his return, he told Henry about the Seventy48, a 70-mile race on Puget Sound. Henry recalled that Ed seemed to be “just sharing a tidbit of interesting news. It was masterful. He dangled this shiny little nugget in front of me, confident that I’d strike at it. And I did. We were off. We would finish TAMO, train like demons, build a trailer crate to transport her across country to Washington, and enlist our wives to play along.” They had six months to prepare.

With the help of Tom Baugher, a fellow member of CABBS, Ed and Henry designed and built a trailer for TAMO, complete with a wooden crate to protect her, and a dolly for single-handed launching and recovery. The crate protected TAMO from the elements on her cross-country road trip and the dolly meant that Henry could launch and recover her while training solo during the weeks leading up to the race.

The Seventy48 was first staged in 2018 and the now-annual challenge, sponsored by the Northwest Maritime Center in Port Townsend, is to cover the 70 miles from downtown Tacoma to Port Townsend in under 48 hours in a human-powered boat. Competitors can travel solo or in a team, but all must travel overnight and unsupported, along Puget Sound, a large body of water with a 7–11′ tidal range.

Henry had rowed thousands of miles but never a distance of this length in one shot, and never at night. Getting race-ready meant long, grueling sessions on the ergometer to harden hands, seat, and muscles. For Ed, the challenge was even greater. At the age of 18 he had rowed with a friend 40 miles across Lake Erie to Canada, but otherwise his boating experience was almost exclusively paddling canoes and kayaks. He was new to feathering oars and rowing with overlapping handles. He, too, put in many hours on the ergometer, and as the weather improved into spring, he got out on the lake as often as he could in the Firefly, putting in the miles until the new techniques came naturally.

Henry went out to Washington three weeks before the race to familiarize himself with the area. Colvos Passage in Puget Sound was an ideal training ground.

With help from CABBS member Tom Baugher, Ed and Henry had designed and built a trailer for TAMO, complete with a wooden crate to protect her and a dolly for solo launching. Several weeks before the race, Henry and his wife, Karen, hitched up the custom trailer crate and towed TAMO the 2,400 miles to Gig Harbor. In the weeks before Ed joined him, Henry familiarized himself with the boat and the waters of Puget Sound. “Although the wind, tide, and currents could be a little tricky, the scenery and the bald eagles were extraordinary. Sea lions surfaced frequently almost alongside and stared at me as I sculled over the kelp beds. I was told that orcas also frequented Colvos Passage, where I was training, but I was glad none ever showed up.”

Before the race Henry rowed a daily practice session out of Olalla Point on the west side of Puget Sound. He gave mixed reviews on the usefulness of a mirror he had borrowed from his cycling gear.

A week before the race, Ed arrived and the two friends rowed TAMO together on three or four occasions, but time was up. They had made it this far: they had built a boat, designed and built a sliding seat, trained hard, and on Friday, June 10, 2022, they rowed out to the Seventy48 start line in Tacoma for the 7 p.m. start. The 116 competing teams included just six from east of the Rockies, and of those six two were from Cleveland—Henry and Ed had been joined by Paul Herrgesell, a fellow member of CABBS who had been inspired by their enthusiasm and signed up.

Fellow Cleveland Amateur Boating and Boatbuilders Society member, Paul Herrgesell, built an Angus Expedition to enter the race. Henry, Ed, and Paul practiced once together at Olalla Point. Paul finished the 70-mile race and placed 30th overall. He boarded his boat in Tacoma, rowed by GPS waypoints, and didn’t get back out of the boat until he landed at Port Townsend—his legs were a bit wobbly.

In the end Henry and Ed would be defeated by the weather. They rowed through the night, taking turns of 60 to 90 minutes each at the oars, rowing into shore for each changeover. By dawn on the Saturday morning, they were, says Henry, “surprisingly alert and buoyant.” They rowed on through the day, but as they rounded Point No Point and turned west for Oak Bay, the wind was building. Twenty-three hours and 53 miles into the race, the “high winds and whitecaps stopped our forward progress. We headed downwind to a narrow, rocky beach to take stock. We huddled on the narrow strip of beach at the bottom of a cliff and realized that with the rising tide, in just a few hours our beach would be underwater and then nightfall would come.”

About 10 miles from the end of the race, Ed and Henry were weather-bound and pondered what to do. In the far distance is the Port Townsend Ship Canal. Above the beach, out of shot, the cliff lifted the direct blast of the wind. In the foreground, the water looks amazingly benign, but in the distance can be seen the building waves and field of whitecaps. This is where they decided to call the race and head downwind for Port Ludlow, some 3 miles away.

They were faced with a difficult choice: either struggle against the wind and waves to the checkpoint at the Port Townsend Ship Canal 9 miles away, or abandon the race, turn southwest, and run 3 miles downwind back to Port Ludlow. They chose safety over competition. By the time they left the beach, the wind was so strong they had difficulty even climbing aboard, but as they finally made their way out, they gained confidence that TAMO could slip through the waves. Progress was slow. Henry remembers that “TAMO rolled and pitched so hard it was impossible to pull the oars. But she bobbed over the whitecaps like a cork and shipped very little water.”

As they left the beach, neither Henry nor Ed was sure that they were making the right decision, but rowing the next 3 miles would take them 2-1⁄2 hours. “It was,” says Henry, “the longest 3-mile row of my life and as we pulled into Port Ludlow Marina, we were disappointed but relieved. We’d made the right call.” And, he says, “It was all good, very good. We met some fabulous people, saw some truly beautiful country, and had a hell of an experience. I wouldn’t have missed the opportunity to do all that with Ed for the world.”

TAMO lies quiet and clean alongside at the Port Ludlow Marina. Saddened to have quit the race, Ed nevertheless pauses to thank the boat for a safe crossing.

Since returning from Washington, Henry has continued to row TAMO on his home waters of Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga River, and in the summer of 2023, TAMO will be part of an exhibit at the National Museum of the Great Lakes in Toledo. He hopes to join Ed in future boatbuilding projects helping, he says, by doing “mainly what Ed tells me to do.”![]()

Jenny Bennett is the managing editor of Small Boats.

Do you have a boat with an interesting story? Please email us. We’d like to hear about it and share it with other Small Boats Magazine readers.

What a wonderful story: a search, a discovery, new skills, new friends working together toward a goal, and a reward – the challenge met and knowledge to share!

As a – let’s say mature – adventurer myself, I have always admired those who have taken risks, managed them, and made good judgements. These kinds of stories, while not often as “flashy” are – to me – far more interesting, even fascinating. The stories of not reaching the summit, of not finishing the race, of retreat to fight again, show intelligence and discernment – but don’t make good headlines or blockbuster movies. It’s too bad really – the ability to turn back is where the wisdom and mastery resides.

I look forward to the further adventures of Henry, Ed, and TAMO!

“Fortune truly helps those who are of good judgement.”

– Euripides

I’m a Whitehall enthusiast – AND, in Seventy48 2022, my wife and I ended up holed up on that same stretch of beach, and ended up abandoning at Mats Mats Bay, just north of Port Ludlow. I will vouch for the conditions being far harsher than the photo indicates! Thanks, I thoroughly enjoyed the story.

(oops, we missed 2022, I was remembering 2021. But anyway, there’s a reason they call it Foulweather Bluff, no matter what year it is.)

Great boat and I love the trailer and bike cart. That rowing event sounds brutal, but having only one rowing station with two adults seems crazy! That’s a lot of ballast! That boat does great with two fixed-thwart stations, so it would fly with two sliders but might be tough to fit.

Could you please provide the source for your outrigger brackets?

Bronze folding outriggers are available from Shaw & Tenney and Whitehall Rowing and Sail.

—Ed.

Thank you.