Harold “Dynamite” Payson, famed small-boat builder, wanted a boat he could row out to the islands of coastal Maine in the morning calm and sail home in the afternoon breeze. He wanted to be able to row standing up, facing forward, as he had done earlier in his life when tending lobster pots off Metinic Island. He was thinking of a sturdy Maine peapod, but wanted something lighter, like a light dory, only more stable. He asked Phil Bolger to design the boat for him and together they brainstormed ideas until both were satisfied. The result was the Sweet Pea.

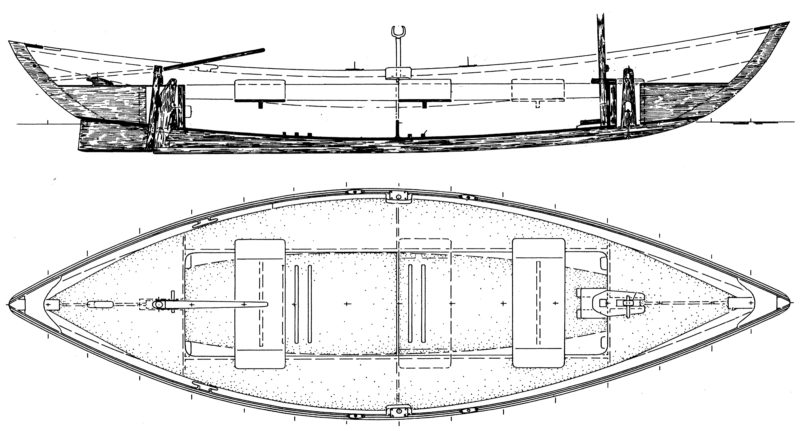

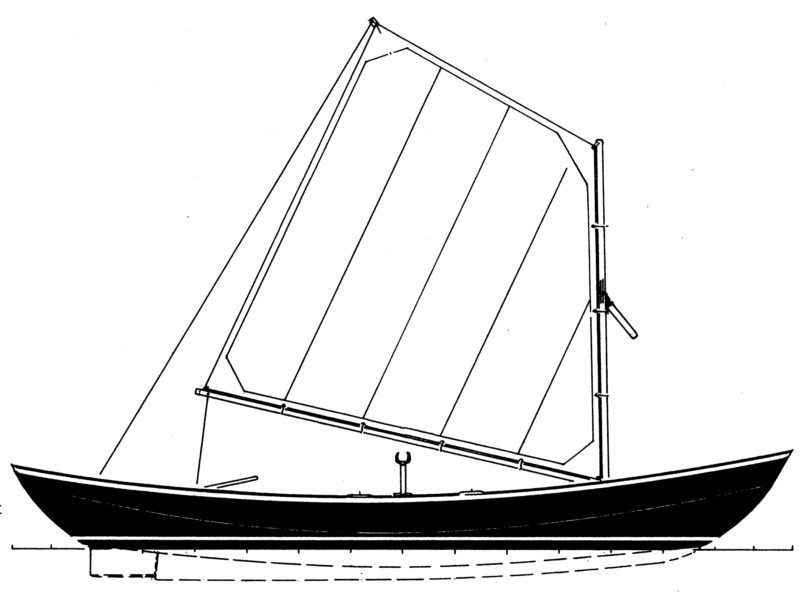

It’s a cross between a peapod and a surf dory, primarily a rowing craft, 15′ in length, 4′ 4″ of beam, and 150 pounds or so when fitted with the spritsail sailing rig, slipping keel, and inboard rudder. For rowing, the sailing rig can be left behind altogether, the slipping keel and rudder removed from their wells, reducing the weight to just 125 pounds.

Ingrid Code

Ingrid CodeThere is no centerboard or daggerboard trunk taking up precious space in the cockpit. On the deck at each end of the foot well, note the green protruding tongues with fids holding the slipping-keel in place. The tiller is folded back to rest in its notch on the sternpost. All spars and oars will stow inside the cockpit. This Sweet Pea is tender to the schooner NINA and hangs in the davits when cruising; a stainless-steel eyebolt with heavy backing plate at the mast partner (mirrored aft) serves as the attachment point for the lifting tackle.

In our case, we were looking for a tender to NINA, our 45′ Pete Culler-designed scow schooner. We were cruising full time and needed a rugged tender capable of carrying a heavy load of supplies or ferrying guests out to the schooner at anchor. We didn’t want a rubber dinghy with an outboard, but something that fit the aesthetics of the schooner—beautiful, in other words. It had to be a good rowing boat, but we thought it would be a lot of fun if we could sail it, too. Dayton Trubee, NINA’s captain, called Dynamite about a new rowing dory that could have a sailing rig also. Dynamite suggested the Sweet Pea design as the perfect boat for our needs. Dennis Hansen of Spruce Head, Maine, built it for us over the winter of 2002–2003, and delivered a work of art as beautiful as it is functional.

Sweet Pea has a multi-chined plywood hull designed for tack-and-tape construction and the resulting rather open seams are filled and shaped with putty before the hull is fiberglassed. Foam flotation beneath the side decks and the buoyancy compartments at either end of the boat will keep it afloat even if swamped. The bulkheads for these compartments, along with the ’midship frame, give support to the hull and help form its shape as the sheer panels are put in place. The bilge panels go on last, completing the hull.

Ingrid Code

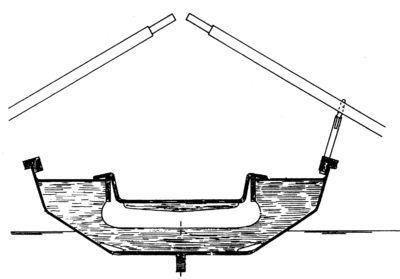

Ingrid CodeThe full-length slipping keel rests against the 1/2″ bottom and is secured only by the two fids fit through the ends of the tongues, which slide into the two wells at each end of the boat. The inboard rudder extends only to the end of the bottom. Sweet Pea’s straightforward, hard-chine construction is evident here.

The two wells for the full-length, 3″-deep slipping keel need to be included in the build only if the boat will be sailed. The slipping keel is an interesting way to go, and eliminates having a centerboard or daggerboard trunk crowding the middle of a small boat. As Phil Bolger describes, the slipping keel is based on those of England’s Norfolk Wherries, 50′- to 60′-long cargo vessels whose keels could be slipped off, while still afloat, before navigating shallow waters, and replaced upon return to deep water. The Sweet Pea’s shallow, full-length keel has two vertical tongues, one at either end, that slip up into small wells that are braced by the bulkheads and decks of the buoyancy chambers. A fid slipped into a hole at the top of each of these two protruding tongues holds them in place above the deck and the keel snug against the bottom.

The round rudderstock has its own deck opening aft of the slipping-keel well; the rudderstock pivots between the coved aft end of the slipping keel and the rounded aft end of the well. The rudder is kept from swinging free when rowing by the wonderfully efficient method of folding the tiller back all the way—180º—to set its end in a notch on the sternpost.

The rowing seats are built in five parts over a jig and are moveable to any part of the boat interior, resting on the parallel ledges that support the cockpit’s side decks. The plans call for two seats, but we’ve found that an extra seat aft (making one deep seat) adds considerably to the comfort of the passenger and doubles as a foot brace for the long-legged rower in the primary rowing position. It works for us because the two seats are butted up against the aft bulkhead. Heel cleats are indicated in the plans, but they’re absent in our boat. When using the forward rowing station, the ’midship frame works well as a foot brace. A savvy builder or owner could add foot braces to fit.

According to Payson, a skilled boatbuilder could complete a Sweet Pea in three weeks to a month working full time. Dynamite Payson’s meticulous instructions on building Sweet Pea in his book, Instant Boat Building with Dynamite Payson, give a detailed account of each step in the process, with a few modifications from Bolger’s suggestions in the plans. All in all, these directions are straightforward and clear, accompanied by photographs at each stage in the process. It would be well-worth studying these 21 pages with care before diving into the project.

Dennis built our Sweet Pea without the stacked foam panels filling the buoyancy chambers as indicated in Payson’s instructions. He left them empty and provided access to the enclosed space with watertight access ports in the bulkheads, two at each end. We’ve found these compartments most useful as places to store a dinghy anchor, a set of stand-up oarlocks, or our lead-weighted sounding line.

Paula Gillikin

Paula GillikinRowed solo from the primary rowing station, the boat is considerably lighter and easy to maneuver. The slipping keel and rudder are still attached in this photo, but can be removed.

There are two conventional rowing stations as well as the stand-up rowing station amidships. The two rowing stations are too close together to allow for tandem rowing but can be used to row solo from whichever rowing station achieves the best boat trim. The Sweet Pea rows well even when carrying a heavy load. We’ve had four adults aboard at one time or two adults with schooner provisions.

Paula Gillikin

Paula GillikinAn unusual feature of the Sweet Pea is its stand-up rowing station amidships. The rower faces forward “to see the rocks before hitting them,” as Dynamite Payson would say. The boat is surprisingly stable when standing. Stand-up oarlocks are essential for this practice.

The amidships station is used for stand-up rowing with tall stand-up oarlocks. One stands aft of center facing forward, propelling the boat by pushing on the oar handles. The motion feels different physically as one rows by pushing forward—and facing forward—rather than pulling the blades backward through the water, looking over one’s shoulder. It’s quite fun! The perspective is different, reminding me of stand-up-paddle-boarding, and approaching shoals are visible well before feeling the surprise of hitting bottom with an oar blade. And the boat is so stable there is no difficulty in being able to stand up and keep your balance. Only a powerboat wake caught beam on will prove momentarily challenging.

We usually row without removing the slipping keel, hoping that we might get in an afternoon sail. It’s easy enough to remove the keel for rowing only, though Payson suggests a skeg be made to fit the aft well to help the boat track straight. Without it, it’ll happily spin in its own length, as I’ve found, and curve off in one direction or the other if I’m momentarily resting on the oars. With the keel in place, coming alongside the schooner or a dock is easily done and the shallow keel will hold the boat in place, keeping it from sliding sideways at the wrong moment. Only a strong side-current or an unusually strong wind will make things difficult, though I suspect that would be the case with any small boat.

Paula Gillikin

Paula GillikinWhen rowing with a passenger, the boat is well balanced using the forward rowing station and bracing one’s feet on the midship frame.

We’ve beached our Sweet Pea many times while out exploring. The breasthooks at each end do make it easier to haul the boat up the beach. It’s doable with one person, but easier with two. We make sure to lift the rudder clear of the sand when beach launching to avoid grit or mud getting up between the rudder and slipping keel, to prevent it jamming the rudder and making it hard to turn. Since we leave the slipping keel in place, even for beaching, we slide a cushion or small fender under the chine to keep the boat upright. We’ve found removing or replacing the keel on the beach requires two people, one to hold the boat up on one side, the other to handle the keel and rudder. It could be done solo if there were a post or tree nearby to lean the boat up against. The operation can be slightly finicky. Because the rudder is braced against the aft end of the slipping keel, we’ve always found we needed to remove the rudder also when removing the keel, and that means removing the tiller with its associated acorn nuts and washers, which have a tendency to slip out of your fingers and vanish down the well. Early on, we removed the rudder and slipping keel much more often—and contemplated having a skeg made for rowing only that would utilize the aft well and lighten the boat. In the end, we’ve found it suits us to leave the keel in place, have the option of sailing more frequently, and accept whatever drag it creates as an improvement in the exercise we get while rowing.

We keep the spars and sail inside the boat most of the time, even if just back from running an errand onshore, in case a breeze pipes up for a little sail. Payson talks about chocks on the fore and aft bulkheads to hold the spars off the ’midship frame and bottom panel, but without chocks in our boat and all spars and sail rolled snugly in one long canvas bag that fits inside the cockpit, the rig is secured with a single lanyard amidships and tucked up half under the side deck and out of the way. When not in use, the 7′ 6″ oars get stowed in their own protective bag on the opposite side, beneath the seats and under the other side deck. It doesn’t take long, 10 minutes at the most, to pull the canvas bag off and set up the little sprit rig. We move the seats into a neat, nested stack forward or aft and sit on the bottom of the boat to sail in light air. There’s more room that way and, with the center of gravity lower, the boat feels more stable. We ended up adding a visibility panel in the sail because it was hard to see under the sail at times.

Paula Gillikin

Paula GillikinIn the right conditions, the Sweet Pea will move along at a nice clip under sail with her spritsail rig, especially bearing in mind her shallow keel and primary purpose as a rowing craft. On the day this photo was taken, the Sweet Pea took off in a rising wind and favorable current, leaving the photographer in the chase boat calling out, “Slow down!”

With the Sweet Pea rigged to sail, the slipping keel shows that it works well in a little sailboat that’s more concerned with rowing and carrying gear than high-performance sailing. The boat doesn’t really like to go to windward, but then that was never the point of the design. Sailing with a nice breeze on or aft of the beam, it goes along smartly and is a lot of fun. For a while we sailed it without the boom—one less thing to carry aboard—but for close-hauled work or running the boat does better with it. We run the sheet through a block attached to a small cleat in the sternpost and it feels more controlled that way, lighter in the hand. In light airs we’ve occasionally “motor-sailed” (rowing while the sail is up), though we’re more likely to take the sail down and just row.

A year or so after we’d got our Sweet Pea, we corresponded with the designer, Phil Bolger, about the boat. His own Sweet Pea was built for rowing only and he was curious as to the performance under sail. He wrote:

“I’ve been wondering if another inch and a half on that keel would gain more in sailing ability than it would cost in rowing effort. This is prompted by an anecdote of a big, three-masted schooner, wall-sided and deep-loaded, which showed an allegedly dramatic improvement in windward performance by a quite small (proportionately!) addition to her salient keel. (She had no centerboard.)”

A home boatbuilder with time to experiment may want to make up a second, deeper slipping keel to see if Bolger’s musings on this improve her sailing performance any without too-great a detriment to rowing.

When I’m out for a row just for the fun of it, maybe to get some exercise, or to explore some new harbor, the Sweet Pea rows along smoothly at a decent pace, steady as can be. In a steep chop, the bow will stomp or slap a little. If the stern is weighted down (usually with me, while Captain Trubee is at the oars), some spray will make its way aft when pulling into a headwind. I’ve never noticed much spray, if any, coming aboard when rowing solo. Payson said the same of the boat. Bolger gives the Sweet Pea a hull speed around 3½ knots, 4 knots if rowing hard. It’s not a race boat and there are some craft she just won’t compete with that way. Recently I rowed with a friend in an Adirondack guideboat fitted with a sliding seat. His paper-light boat flew along, gliding across the water with great ease and speed. But, on quick reflection, I considered how tender his boat is, how limited the conditions are for safely taking it out, the loads it can’t carry, its lack of a sail, and my momentary envy yielded to a solid appreciation for Bolger’s sweet design.

We once had our Sweet Pea out in a bad squall, trying to row back to the schooner out at anchor; the wind gusted across the tops of the waves, rain poured down, and lightning was all too close. Our success that night was partly due to the skill of the rower, but also to the boat itself with its seaworthy design and solid construction. We never felt at risk of being swamped and knew even if we were, the boat would stay afloat.

After more than 17 years of continuous service, very little about her has needed attention, besides cosmetically. The one area that should not be neglected is the insides of the slipping keel wells and the tongues on the slipping keel. We had left the keel in place a little too long and it was only on removing it for maintenance that we discovered some wood hidden up in one of the wells (and along the corresponding slipping keel tongue) that needed the attention of a shipwright. Take care that these areas are well sealed in the building process and then remove the slipping keel and rudder periodically to inspect. Otherwise, our Sweet Pea was remarkably solid after considerable, hard usage as tender to the schooner.

The Sweet Pea is the perfect little hybrid vessel that fits our needs perfectly. It’s a handsome boat with pleasing lines and, despite the modern construction, has a heritage in its workboat ancestors. It’s an able, sturdy, rowing/sailing, weight-carrying double-ender with a graceful sheer and a penchant for exploring beautiful harbors and creeks in myriad anchorages, sailing along the sedge, taking us for picnics on deserted islands, and carrying loads of provisions out to the schooner. It tows well behind the schooner when the need arises and is light enough to be carried on the davits with ease. We’ve cruised NINA from Bar Harbor, Maine, to the Dry Tortugas and all points between, and our Sweet Pea has been an indispensable part of that—a great joy to row and sail.![]()

Ingrid Code is a sailor, freelance writer, and musician who sails aboard the Joel White-built scow schooner NINA. Currently sailing south for the winter, she has spent the last twenty years exploring the rivers, creeks, bays, sounds, and byways of the US East Coast.

Sweet Pea Particulars

[table]

Length/15′

Beam/4′ 4″

Weight/150 lbs

Sail area, sprit/43 sq ft

Sail area, leg o’ mutton/59 sq ft

[/table]

Plans ($45) and full-size patterns (rowing and sailing, $105; rowing only $85) for the Sweet Pea are available from H.H. Payson & Company. Instructions with measured drawings are included in a 19-page chapter of Instant Boatbuilding with Dynamite Payson, available from The WoodenBoat Store for $21.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Wonderful and scholarly as well as deeply practical article. I know the boat but never had such a thorough exposition of the details. Excellent piece generously and thoroughly illustrated. This is my first encounter as well with your interesting magazine.

Kent Mountford, PhD

Estuarine Ecologist and Environmental Historian, U.S. Coast Guard licensed captain for 30 years.

I built a Sweet Pea a long time ago. The slipping keel is an ingenious device but it requires that you commit to rowing only or sailing before the boat goes in the water. You can’t make the change once the boat is afloat. Mine had the keel permanently fixed (glued and screwed) to the boat with no “cases.” I’m sure this degraded rowing performance, but without another boat to compare it to, I can’t measure it. I was satisfied with the performance under oars. With a very small sprit sail, I found sailing performance to be pretty weak However, a subsequent owner used to sail out from Charleston to Fort Sumter where tide, river current, and a brisk sea breeze can make for challenging conditions. He thought it was perfect.

My boat was built with AC fir plywood and sheathed in fiberglass and polyester resin (epoxy was not yet in common use). It has been 20 years since I heard about her, but at that point, the construction had held up for about 20 years.

For a messing-around boat, the Sweet Pea is a great choice.

I, too, fell in love with Sweet Pea. I particularly loved how the bilge plank swept up to the bow. I bought the plans, just waiting to be transferred to wood and cut. While reading your well-written and comprehensive article, I researched NINA and fell in love with her. She is reminiscent of a former love of mine, a 33’x14’x3.5′ Hampton Flattie built in the early ’60s. Her house was 10’x23′, a 25-gallon water tank on top provided gravity-fed fresh water, gaff rigged, a Chrysler Crown occupied the space where the centerboard would have been. The cabin rose 4′ off the deck. There was no sitting down and steering. It was a downwind sailing houseboat. I really loved living and cruising on that boat in NYC waters. What struck me when I studied NINA’s reconstruction photos was the cabin top edge joinery and the windows. They were practically the same as my old boat. I wondered if it was the same builder. I’d like to contact the builder to see if he’s one and the same. I love the husky, unadorned, workmanlike design and build of NINA. Thanks for article.

We also built one of these lovely boats (2006) and still use her every year. She lives on a trailer and is rowed in Quartermaster Harbor, Vashon Island, Washington. Although we constructed the trunks we never had the inclination to add the (unbuilt) slipping keel. This was in part due to a (snail mail) communication with Phil who wasn’t too excited about rigging “perfectly good pulling boats for sailing.” Our boat is made from AB fir marine plywood (still OK-ish then) glassed (per spec) set in System 3 epoxy and painted with their LPU paint. This has held up well. We used open rails (just because) and the bottom is smooth except for two ski-like parallel strips of UHMW screwed onto some built-up plywood sub foundations for dragging onto our rough beaches. This has worked well although some sort of small skeg would improve tracking. We did discover though that having a rowing compass helped with course keeping. With a bit of practice pulling a bit more on one oar or the other becomes automatic. I would add a skeg or keel though if we were more adventurous in our voyaging.

The design has been on my mind since the How to Build article in WoodenBoat, I have Dynamite’s book on building her too. It is time to get serious about her, I suspect one would account herself well.

I built mine about 28 years ago. It’s been a great boat. A few suggestions: I made new seats, deeper than the design in order to use a flotation cushion and still be at the proper height. I also made a 3′-long skeg to plug into the rear well when rowing. This makes it track much better with the keel removed and produces noticeably less drag than rowing with the keel in place. When rowing with two people, another useful accessory is a very short tiller to replace the sailing tiller so I can sit in the stern and steer while the wife rows.