photos and video by the author

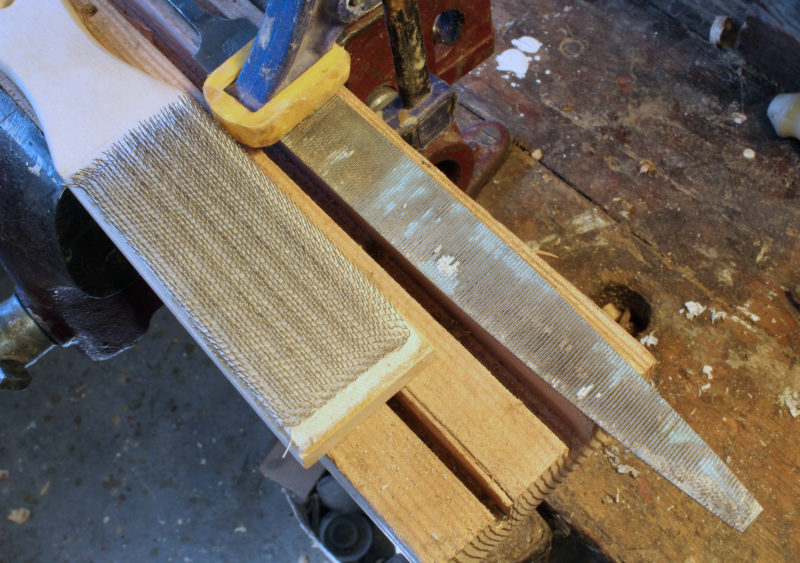

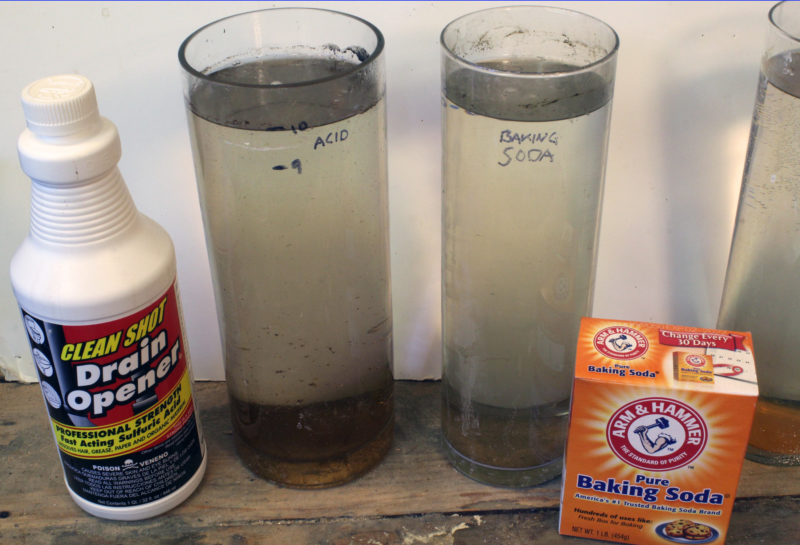

photos and video by the authorMy equipment includes three glass flower vases I bought at Goodwill for 69 cents apiece. A thin stick and some small spring clamps hold the tangs out of the acid. Drain cleaner provides sulfuric acid to etch the files and a saturated baking-soda solution neutralizes the acid. The third vase has a fresh-water rinse. The file card (lower left) cleans file teeth and shop-made tools of copper, brass, and steel remove the debris the file card leaves behind.

Files don’t get the attention that planes and chisels receive, but they are cutting tools too work best when they’re sharp. Because files are made of hardened high-carbon steel and their teeth are numerous and small, the easiest way to sharpen them is with an acid. I’ve used vinegar—acetic acid—and drain cleaner—sulfuric acid. The acids react with the iron in steel, removing metal from the surface. A dull cutting edge is rounded over with wear, and as the metal dissolves, the radius of the curve diminishes and the edge gets sharper. Before putting acid to work, the file needs to be cleaned. Anything stuck between the teeth will prevent the acid from getting to the metal. A wire brush will get some of the debris left by the work, but a file card, with its short, stiff wire bristles will do a better job.

I work files with my vise holding a block of wood that I’ve run through the table saw to make a raised lip along to restrain files set on the flat and a couple of grooves to hold files on edge.

A pistol-grip bar clamp with padded jaws holds the file for cleaning. This file is clogged with paint. Its back is rounded so it covers a bit of the lip on the wood block.

The first step is to scrub the file with a file card. If you don’t have a file card, use a stiff steel-wire brush. Even after a thorough scrubbing, some debris remains.

If there is still debris stuck fast in the gullets between teeth—paint, epoxy, and aluminum are my usual culprits—a piece of copper pipe with one end flattened or a piece of brass will dislodge it. Pushed parallel to the file’s teeth, the copper or brass will wear away, creating a saw-tooth-like edge with tips that reach down into the gullets. For very stubborn debris, piece of mild steel, heated and hammered thin and flat, is the most effect cleaning tool I’ve found. I used a piece of 1/4” steel rod; a big ungalvanized nail could work too.

Whatever debris that the file card leaves behind can be forced out by pushing parallel to the grooves with metal softer than the file’s hardened high-carbon steel. Here a flattened brass rod does the work on a 4-in-1 rasp and file.

The flattened end of a piece of copper pipe can also work down into the grooves. For stubborn bits of debris, called “pins,” angle the flat edge of copper to apply pressure with one corner.

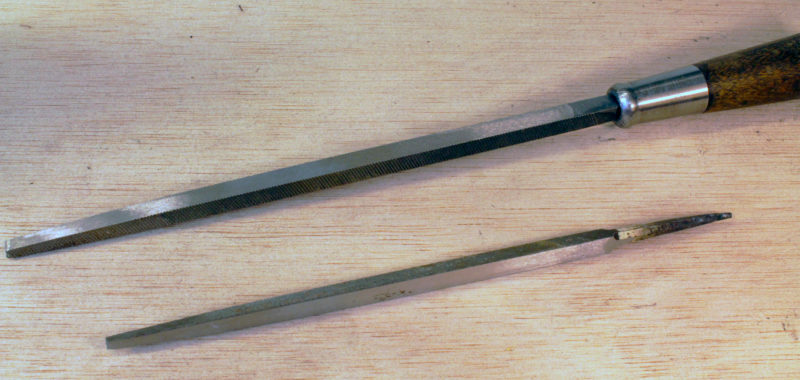

I made this file cleaner from a length of mild steel 1/4″ rod that I heated to red-hot with a propane torch and hammered flat. Pushing the tip parallel to the file’s grooves quickly creates an edge of teeth that will chisel out debris. The soft steel won’t damage the file. The same grooves develop when using copper and brass to push the pins out.

White vinegar is often recommended as the acid for sharpening files. The type you’ll find for kitchen use is 4-percent acetic acid. There’s also a 6-percent cleaning version that you’d find at the store among household cleaning products. Even the stronger version is very slow at etching a file. I found that after three days it would begin to make slight progress. The sulfuric acid that is available as drain cleaner is much more aggressive and can do the work in about an hour. The Clean Shot Drain Opener I bought at a home improvement store is 93 percent sulfuric acid. It contains “metal inhibitors,” but they clearly don’t prevent the acid from sharpening files. This high concentration of acid makes the product very harmful if it gets on you or almost anything else, so it requires handling with care. I wear glasses, the full face shield I use for lathe work, rubber gloves, and an apron.

This drain opener with 93 percent sulfuric acid, gets diluted with water to a 10-percent solution that can sharpen a file in about an hour. When the acid is poured into water it generates heat, so I prefer to use glass instead of plastic containers that might get softened when warmed. I bought these three glass flower vases at Goodwill for 69 cents apiece. I prefer the vases over glass baking dishes because I can suspend the files and keep the tangs away from the acid and dry for safe handling. The vases also give the acid less surface area to emit vapors and I can clearly see the acid at work. In a baking dish the bubbles would obscure the view through the surface of the liquid. I marked the acid vase with levels for the water (9) and the acid (10) so I could easily make the solution and require I pour the water in first. The other vase gets filled with water and then baking soda is added until no more can be dissolved. The third vase, to far, right is water for rinsing.

The acid is too strong to use undiluted; 10 percent acid/90 percent water is strong enough. Never pour water into acid. It can splatter and raise a little cloud of vapor because of a quick exothermic reaction. You’ll notice that a bottle of sulfuric acid will feel heavy. It is almost twice as heavy per unit of volume than water. When poured into water, the 10-percent solution will noticeably warm up, which is why I prefer glass containers to plastic. Keep away from the vapor rising from it by working outside or wearing a respirator.

Prepare a baking soda solution to neutralize the acid after the file has been etched. Mix baking soda until the water can dissolve no more and soda begins to accumulate at the bottom.

Before you immerse the file, check how sharp it is by pressing a fingertip against the teeth and slide it toward the tang. With a dull file, you’ll feel some resistance but won’t feel the teeth catching the skin.

Submerge the file in the acid solution and give it a gentle swirl to dislodge any air bubbles. The chemical reaction will quickly produce very small bubbles of hydrogen. The acid does the work in about 60 minutes. To check the progress, I remove the file from the acid and rinse it in water. I do the same fingertip test and when I feel the teeth catching, the sharpening is done.

Dipping the file in the baking-soda solution will neutralize the acid. The residual acid on the file will produce a flurry of carbon-dioxide bubbles. Rinse the file with fresh water and dry it with a heat gun, hair drier, or a blast of air from a compressor.

After dipping in acid, baking-soda solution, and water, the file needs to be thoroughly dried to keep from rusting. When the file is dried, rubbing chalk or soapstone on it will absorb any remaining moisture. I lightly brush the excess off with a brass-wire brush. Soapstone, often carried by art-supply stores for carving, is slippery stuff and leaving a thin film on will, for a while at least, prevent clogging when the file is in use.

Some do-it-yourselfers spray a lubricant such as WD-40 on the file to prevent rust, but I find that gets pretty messy and the lubrication might make the teeth slide across the work rather than cut into it. Rubbing chalk or, my preference, soapstone over the teeth will assure the file is dry and won’t rust, and then help prevent clogging when it’s being used.

After rubbing the newly sharpened rasp with soapstone, I use a brass-wire brush to clean up.

To dispose of the sulfuric acid solution, I fill a 5-gallon bucket half-full of water and pour the solution in. Next, I slowly pour the baking-soda solution into the bucket. It creates a lot of froth as carbon dioxide bubbles up from the reaction. The mix is still likely to be acidic, so I sprinkle in baking soda, straight out of the box, until the frothing stops. It can take a whole 1-lb box. At that point, the mix in the bucket is no longer acidic and the remaining by-product of the reaction is a solution of sodium sulfate, a neutral salt. It is safe to pour down the drain—it won’t harm plumbing—and isn’t an environmental hazard. The sodium and sulfate ions in the solution are, according to the source linked above, “ubiquitous in nature.”

While you’re devoting some attention to sharpening your files, consider grinding the teeth off one side. Some flat files come with toothless safe edges to assure you’re only working one side of an angle. I use square files for cutting through-mortices in the gunwales of Greenland kayaks. With cutting faces on all sides, it’s difficult to tune the corners accurately.

Grinding a safe edge on a file can make it easier to work accurately, working a corner one surface at a time.

By making one face smooth I can concentrate on one mortice surface, knowing the adjoining surface will be unscathed. I remove the teeth with a bench grinder and a 1×30 belt sander/grinder. As an added benefit, the intersection of the safe surface and the cutting surface will cut a sharp, precise corner. The file’s original edge cuts a slightly rounded corner.

All of these files and rasps got a better bite after a dip in the sulfuric acid solution.

After you’ve sharpened your dull files, treat them with the same care you accord your other cutting tools. Keep them separated from each other instead of tossed together in a drawer. ![]()

Christopher Cunningham is editor of Small Boats Monthly.

You can share your tips and tricks of the trade with other Small Boats Monthly readers by sending us an email.

Thanks for a useful article on an obscure subject. Files are integral to my boatbuilding endeavors, for both metal and wood.

Thanks for a great article! I had no idea files could be sharpened, much less so easily. I generally pick up files at thrift stores to replenish my dull ones, but I’m too cheap to throw out the old ones, thinking that hardened steel will be useful for something someday. Now I’ll resharpen my collection of dull ones!

Thanks for the article. I’ve long known about this but intimidated by lack of practical information. I’ve got a patternmaker rasp I’d really like to treat, but I think I’d better start small, like an 8″ mill bastard.

I’ve often wondered about using acid to sharpen files and now I know. It makes me think that this could be the solution for sharpening dull bandsaw blades as well.

I wouldn’t chance sharpening bandsaw blades with acid. While the acid is sharpening the teeth, it would be eating away the rest of the blade, making it thinner and weaker.

Galvanic etching is an alternative to using acid and doesn’t carry the same risks. The process is actually the same that eats up precious metal in boats (electrolysis). In this case, however, we would substitute a file for the sacrificial anode on the boat. DC power, the positive lead to the file, negative lead to a cathode (I use a hunk of brass or copper but any conductive metal will do). Submerge all into a salt water bath. Experiment with amperage, voltage, and salinity. I use a variable DC power source but others have used 12 volt batteries with success. This same set-up will remove old nasty chrome from any bronze or brass plated fitting. Bonus!

Interesting, informative & another great reason to subscribe to Small Boats Magazine.

I clean a lot of files by dipping them in vinegar. I never knew how to sharpen them though. This article has helped me very much.

Thanks for the posting. I had a file that I was ready to throw out. The teeth were so clogged that it felt smooth. I tried using a file brush but to no effect. I soaked the file in 5% vinegar for a very long time and now it is like new.