Going to Lowell’s Boat Shop in Amesbury, Massachusetts, is like going to a dory candy store. Do you pick a straightforward rowing dory like the Salisbury Point Skiff, developed in the 1860s? How about the outboard-motor-powered version of the Amesbury Skiff, an adaptation from the 1920s? What about a high-sided Banks Dory, set up for traditional tholepin rowing? Having but one choice to make, I selected what I thought for me, and I suspect for many others, would be a fine compromise: a Sailing Surf Dory.

Corinne Ricciardi

Corinne RicciardiA comparatively round-sided dory, the Sailing Surf Dory handles well under sail or oars. This boat is a 14-footer, and Lowell’s Boat Shop in Amesbury, Massachusetts, also builds 16’, 18’, and 20’ versions.

For many dories, the words “sailing” and “rowing” don’t comfortably sit side by side. If performance sailing is of paramount importance and you break out the oars only grudgingly, look elsewhere. If keeping up with the collegiate rowing teams along the Charles River in Boston is your ambition, don’t even think about a boat that has anything like the word “sail” in its vocabulary. All boats are compromises, and the only question is whether the compromise works well or works poorly for its intended function in the hands of its owner.

Lowell’s Boat Shop made thousands of dories in the schooner-fishing era and has a tradition dating back to 1793 in Amesbury. The combined boatshop and museum, now a nonprofit organization, is worth a visit in its own right. Dories built here using jigs and patterns polished by use and time have been shipped far and wide. “All that we build we build from patterns that are here at the shop and notes from the original builder,” lead boatbuilder Graham McKay said. “John Gardner has a few plans for boats like this, such as the Nahant Dory and the 19′ surf dory in The Dory Book, but our design is indigenous to the shop and based on 19th-century patterns. Likely some of the boats Gardner recorded were similar surf dories built here…or they were closely based upon them.”

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonThe nonprofit Lowell’s Boat Shop fulfills roles as a working boatshop and also as a museum. Dories are built here using strongbacks and templates that date back many decades.

Lowell’s makes the Sailing Surf Dory in four sizes, 14′, 16′, 18′, and 20′. On a fine day with a fair breeze, I took a 14-footer for an afternoon sail on the Merrimack River during the high slack tide. The boat was 33 years old, built by longtime Lowell’s builder Fred Tarbox. She had been donated back to Lowell’s by her owner after long service. The boat was in excellent condition, a testament to her builder and the care she has received during her lifetime.

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonThe Sailing Surf Dory, at front, is one of many dory types built at Lowell’s on a site that has a boatbuilding tradition extending back to 1793.

This particular boat was rigged with a single sliding gunter sail. Other rig variations are possible, among them the traditional dory combination of a long-footed triangular mainsail with a small jib. For solo sailing, I found the sliding gunter to be a fine choice. It has ample sail area, and it’s easy to handle. The rig is something like a very high-peaked gaff rig, with the gaff nearly parallel to the mast. Its particular advantage is that the mast can be quite short, making the entire rig easy to stow inside the boat when rowing.

The boat is handy, responding well to her helm and easily making stays, or turning from one tack to another, leaving no doubt of her ability to cross the eye of the wind. The sheeting system is the only thing that might offer a novice some consternation, but with a bit of practice it becomes clear. The system is a common one for dories and a few other small-boat types in which a single-part sheet passes around one of a pair of very simple thumb cleats mounted on the inwales well aft, one on each side. When you tack, you free the sheet from one thumb cleat and pass it around the other one, which will be on the leeward side on the new tack. There is no provision for cleating it off, nor should there be: Get used to keeping it in your hand, where you can instantly let it go in a gust. This sheet-shifting can seem awkward at first, but very soon the sailor develops a strategy to guard against having the sheet run afoul of the long tiller.

Corinne Ricciardi

Corinne RicciardiWith no standing rigging, the rig is easily struck completely when it’s time to row. Here, the mast heel is run under the rowing thwart and the masthead and spar extend just a bit past the transom.

The sheet really must be shifted when sailing close-hauled, not just because doing so assures the best sheeting angle for the sail but also because it’s the best way to keep the sheet clear of the tiller. When jibing, however, I found that it is much simpler to leave the sheet on one or the other thumb cleat and forgo shifting it. On downwind points of sail, this has a negligible effect on sheeting angle, and leaving the sheet on one cleat means that jibes can be done one after the other in quick succession with very little effort or disruption. I simply held the tiller and sheet together in one hand and grabbed the clew with the other to pass the sail across the boat for the new tack.

The boat is fitted with a daggerboard, which is sensible for a dory. The board can be raised fully for downwind sailing, and it allows a continuous adjustment for any given point of sail. It requires no complicated gear, and its top is well supported by the rowing thwart. The trunk’s short length minimizes intrusion into the interior. Forgetting to raise the board when nosing into a beach, however, would bring a memorable reminder, and venturing too close to rocks risks not only harming the board but also wrenching and possibly damaging the trunk. Having simple and uncomplicated rigging perhaps leaves the mind free to pay close attention to that board.

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonA daggerboard helps the dory track while sailing, and the fitted cap (below) keeps the water at bay while rowing.

When it comes time to row, the dory’s sail bundles easily around the mast, spar and all, where it can be made off with a short length of line or the end of the sheet. There is no standing rigging. The halyards— there are two, throat and peak—are made off to cleats mounted on the mast above the partners. This means that the whole bundle can be very easily lifted free and stowed in the boat. When I row a boat like this one, I like to pass the heel of the mast under the rowing thwart and let the top end of the mast trail over the transom. This keeps the rowing thwart clear.

Tom Jackson

Tom JacksonThumb cleats on the insides of the rails, far aft near the distinctive transom, provide a good sheeting angle.

Dories can be remarkably agile under oars, and they can also be very comfortable to row. The surf dory steps up nicely to its pace, and with its well-rockered bottom it comes around sharply. No dory will track as well as a long-keeled, round-bottomed boat, but steady rowing rewards the oarsman with a reasonably straight course. One benefit of a dory is that when you come to shoal water, you can adroitly turn it around and row effectively backwards, allowing you to see any rocks and maneuver around them. When beached, this boat will also remain upright on her flat bottom.

Corinne Ricciardi

Corinne RicciardiDownwind, it is possible to leave the sheet on one thumb cleat to simplify quick jibes.

I sailed in a fairly light breeze in protected waters, but I wouldn’t hesitate to do some adventuring in this boat, especially the larger versions of it. Dories are famously capacious, and with dry bags for gear, camp-cruising for a solo sailor or a couple would be a tempting possibility, especially if tenting ashore. The boat has no floorboards, so it would be difficult—but not impossible—to set her up for sleeping aboard. The 18′ and 20′ versions, especially, would be robust trekking boats for cruising to islands in at least somewhat protected waters. Like many boats, this one will probably take more weather than the skipper will—and it’s worth remembering that for a century the old U.S. Life Saving Service, before the days of the Coast Guard, relied on surf dories like these.

With effective reefing systems, wise choices of ground tackle, and a willing oarsman, this boat will go places. At 230 lbs for the shortest boat and 400 lbs for the longest, any of these dories would do well on a trailer for expeditions to new territory. And once set up to the owner’s taste, new territories will always beckon.![]()

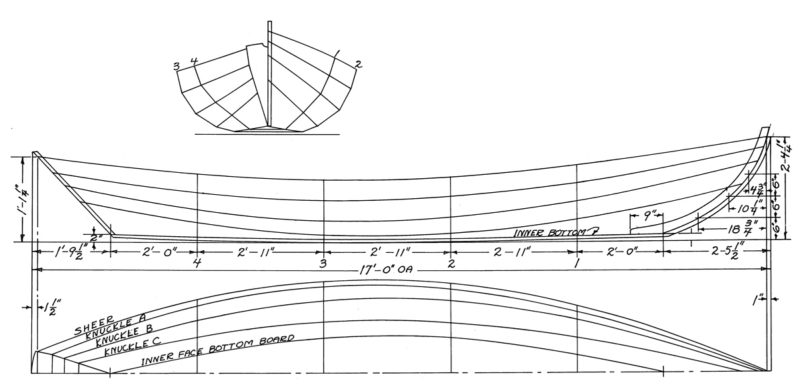

Because Lowell’s Boat Shop uses templates and patterns, no plans exist for the boats built there—and Lowell’s built them by the thousands back near the turn of the 20th century, especially for the Gloucester fishing schooners. Mystic Seaport’s John Gardner reproduced lines for some boats, and one that comes close to the Sailing Surf Dory shape is the Nahant Dory shown here and published in The Dory Book. Note, however, that it was not set up for sail and that with 4’2” of beam for its 17’ length, the Nahant Dory is much narrower than the 14’ Sailing Surf Dory with a beam of 4’11”.

The Lowell Boat Shop / Museum offers classes in wooden boat building. I took two hands-on classes, taught by Graham McKay and his right-hand man Jeff: Pete Culler’s 13’ Good Little Skiff and a 15’ Amesbury Skiff – both hulls of traditional clenched copper nail lapstrake construction. I won the latter in the end of class build raffle and felt a bit of history. Other courses such as lofting (the boat in this article) and making a set of spruce oars were also very interesting. Great to be (relatively) near this historic shop-museum.

E. Strizhak

Framingham, Ma.

Beautiful boat. The 14 feet are the waterline, so it’s as big as my CLC NE Dory. The only thing I would hate is the tiller. It looks uncomfortable.