In November 2013 I received a phone call from Tommy Hudson, good friend as well as one of my employees. After we chatted for a bit, he said he loved his job but there was something he really wanted to do: row across the North Atlantic. I was instantly inspired; I told Tommy he could go and I was going with him. He laughed and agreed.

Pete Fletcher

Pete FletcherOn arriving in Australia, MACPAC CHALLENGER took up residence in my garden shed. We started on what was to be just a new paint job, but we found lots of rot and removed most of the cockpit interior structure and even some of the hull.

We spent the next 15 months raising sponsorship and rebuilding an old, wooden, ocean-rowing boat that we hoped would survive the North Atlantic. Things started slowly, but then, thanks to the generous support of Macpac, an outdoor clothing company, and World Challenge, the organization where Tommy and I both worked, we began to make good progress, and our boat became MACPAC CHALLENGER, or MC for short. While the name conjured up an intrepid image, that was certainly unmatched by the reality. As we stripped MC bare with the help of Melbourne boatbuilder Dave Parker, we found more and more unsavory parts. She’d been left to sit out in the elements for two years after her third transatlantic crossing and the neglect showed. There was rot in the bulkheads and in the hull, and at one point Tommy put his hand right through the plywood with no effort at all.

David Briggs

David BriggsWhen we shipped MACPAC CHALLENGER to New York, we had finished the main structure, rowing setup, and basic safety components, but still had to obtain and install the electrics and autopilot. The cabin pump, its hose visible on the left side of the cabin, could bail the cabin out in the event that it flooded while the boat was capsized. David Briggs made the decals in our absence and must have had a good laugh, sticking “Row, row, row your boat” decals all around the cockpit. After just two days at sea we vigorously scratched off most of the words, but it was too late and the song was indelibly etched in our heads.

The refurbishment was more extensive than we’d imagined, but it gave us the opportunity to redesign aspects of the layout for what would be a longer, more arduous crossing than the boat had ever undertaken. We repositioned the watermaker—our most vital piece of gear—inside the cabin for protection from the elements, replaced the deck with thicker plywood, and reinforced the main cabin framing.

David Briggs

David BriggsMACPAC CHALLENGER was trailered to the Melbourne airport for her cargo-plane flight to New York. The scuppers visible in the side would drain most of the water that might wash into the cockpit, leaving only the footwell to pump out.

Our project ran long and over budget, but MC was eventually shipped from Melbourne to New York in February 2015 and we felt confident she’d be ready in time for a May departure.

The night before I flew to New York, Willow, my eldest daughter, just five years old, asked me why we were going. My answer—“To see what it makes of us”—was for both me and Tommy, even though he had told me only two days earlier, at our going-away party, that he had problems in his relationship with his fiancée, he’d been diagnosed with depression, and he didn’t know if he’d come on the row. Tommy was one of the only people with whom I’d embark on this kind of journey, but he had a difficult decision to make: If he came he risked losing his fiancée, and if he stayed behind he might never learn to live happily. I left Melbourne 24 hours before Tommy did, with the nagging question: If it came to it, would I go alone? It was a major relief the following night when I pulled up at the Newark airport and saw a smiling Tommy, standing in the chilly, springtime, New Jersey air.

With the help of ocean-rowing record holder, Simon Chalk, we got down to work. Our confidence in the preparedness of our boat was seriously misplaced. We still had to install the electrics and the autopilot, and we had no choice but to join the boat-shop queue with every other boat owner on the East Coast. The whole project had been a race against the calendar and we missed two good weather windows while we were in Brooklyn working on the boat.

Our autopilot was not meant for ocean-crossing rowing boats and there was no easy way to mount it and protect it from breaking seas. We finally installed it on the gunwale, but when we turned it on it didn’t work. Our fortunes began to change when Wayne, a talented marine electrician, replaced the motor and announced, at 7 p.m. on the 20th of May, that the autopilot worked. We were exhausted, our funds were depleted, and the sun was literally setting on our time in Brooklyn: With the wind from the northwest and the high tide at 10 p.m. that same evening, this was our chance to go.

We rowed west from the marina, staying north along the shore to keep out of a strong northwest wind, and then turned south for Rockaway Point. Wayne had warned us about breakers near the channel there and said, “Get ready to row like hell.” Our adrenaline must have been pumping, because at one point we radioed what we thought was a boat in our path only to find out, after the third unanswered call, that it was an oversized channel marker. The fast-flowing ebb shot us out toward the Atlantic; we set a course to the southeast to get offshore as quickly as possible.

In the morning we were disappointed that we could still see New York looming large behind us. Tommy noticed the compass wasn’t working, so we searched for a small screwdriver to remove and recalibrate it, but the smallest screwdriver we had didn’t fit! Although we eventually managed to remove the compass, I had the ominous feeling that we may have left other important equipment behind, and indeed the screwdriver would turn out to be just the tip of the iceberg.

On day four, the autopilot ram pulled out of the gunwale. We got it stuck back in place but eventually the motor blew. We were still within easy sight of the Empire State Building, and had no way to manage the rudder while we were rowing.

Pete Fletcher

Pete FletcherTommy cobbled together our foot-steering system and got it to move the rudder effectively. The failed autopilot ram is visible at lower left. The foot steering was an early success but an ominous sign of other trials to come, as Tommy later had to fix many of our other key components, including the compass, rear hatch, solar panel, and GPS.

I did my best to keep the bow straight in the waves while Tommy built a foot-operated steering system with odds and ends we had aboard. It looked makeshift but we could finally move the rudder with a twist of a foot. This old-fashioned steering would add days to our crossing, but our fortunes would no longer be tied to the hapless autopilot and the constant din of its motor. A calm came over the boat and for the first time in nearly two years there was nothing else to do. We were rowing; we were free.

That evening Tommy called me out of the cabin, telling me to bring the camera. I came on deck and was mesmerized by a huge shark swimming right next to us. It was majestic and over half as long as our boat. Tommy told me to put the camera in the water, and though I seriously considered throwing it to him, we were just four days out and I still felt I had something to prove. I knelt down and got my arm far into the water and came almost face to face with the shark. It let me keep my arm, and after a few moments moved slowly on its way.

Pete Fletcher

Pete FletcherWe painted our carbon-fiber oars pink in support of a breast-cancer support organization. We started with eight oars onboard, but dispatched two along with other marginally useful gear to lighten our load. Tommy and I wrote our contact information on the oars in case they showed up on some distant shore. Here, early in the trip Tom’s beard is meager and he is still looking robust in his black T-shirt–the first of three, each worn daily for one month.

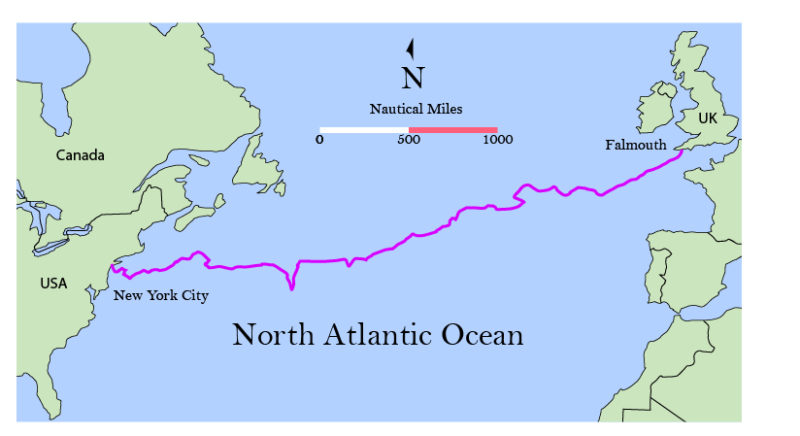

With a northwesterly wind in the forecast, we made the decision to forgo the more direct, northerly route in favor of using the wind to reach the Gulf Stream to the south, where we knew we’d make better progress. We rowed hard, but hadn’t anticipated an unfavorable current that trumped both our tailwind and our puny efforts at the oars. After five agonizing days we finally started moving eastward in spite of a 15-knot easterly wind. We’d made it to the Gulf Stream! Frustrated by my arm-rowing technique, Tommy decided it was time to teach me how to row properly by driving from the glutes and quads, and with my improved stroke, a current in our favor, and the wind strengthening from the southwest, we flew along, hitting a new top speed almost every hour. As 15′ following seas began to break, we hurtled down from the crests. I feared MC would nosedive in the trough, but each time she lifted her bow just in time.

We covered over 250 nautical miles in three days and recorded a top speed of 17 knots, later learning that MC’s longest day, 116 miles, had broken the Ocean Rowing World Record for the greatest distance ever covered in 24 hours. We’d had incredible conditions, but MC, a wooden boat in her twilight years, deserved the accolade.

Tommy Hudson

Tommy HudsonThe first time I deployed the sea anchor it was without the trip line, a mistake that could have cost us the anchor. Confucius came to mind: “I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.” I never again forgot the sea anchor’s second line. Deploying the sea anchor helped cut our losses in unfavorable winds, but resorting to it was often followed by a consolatory cup of tea as we watched our hard-won miles disappear.

Our first storm came a month into the crossing. The wind blew 40-plus knots from the south all day, creating 20′ seas. We were exhausted and at dusk debated whether we should stay on deck to keep the boat from going beam-on to the waves and potentially rolling, or hunker down in the cabin for the night. We decided to retreat and put a small drogue out to keep MC’s stern to the waves while we slept.

Tommy Hudson

Tommy HudsonIt was rare for both of us to be in the cabin and usually that meant tough times, sitting it out on the sea anchor, with regular trips outside to look at the sea state determine the wind direction and strength. The quarters were cramped but with our photos and messages from loved ones, the cabin was our sanctuary.

Breaking waves crashed over the cabin with a mighty force but we were so tired that sleep came easily. It didn’t last, and we woke suddenly in the pitch black at around 2 a.m. as MC pitched violently to port. A moment later we were lying on the roof of the cabin surrounded by water. Our seat belts, which we used to strap ourselves to the cabin sole, had broken and with all the water around us it seemed as if the cabin had fractured. There was little we could do but trust that the ballast would bring us back up. MC rose and fell with several waves but remained inverted, so Tommy and I clawed up one side of the cabin and after few more waves, MC righted herself. I got my foulweather gear and harness on, got out on deck and closed the hatch as quickly as possible. In the dark it was hard to judge the extent of the damage, but it was clear that we’d lost the drogue, the stern bridle, and the main bilge pump.

When dawn emerged, we could fully assess the boat’s condition. The battery monitor indicated we were almost out of power and the GPS was completely shorted. We could have limped on without navigation and communications equipment, but we needed power to run the watermaker, so we simply had to maintain the electrics. We found water seeping through the hull into one of the battery compartments. To keep the water from destroying the battery, Tommy drilled holes down low in the battery compartment partition so water could drain into the footwell where we could easily pump it out.

Pete Fletcher

Pete FletcherLow-pressure systems bringing wind and rain were a common occurrence and waves would often grow too large to negotiate with the foot-steering system. Here Tommy is holding the hand steering lines to keep the stern into the waves.

At our going-away party we’d had a sweepstakes to predict how long the crossing would take. Guesses ranged from 60 days to over 100, and Tommy and I guessed 75 days. With winds so rarely in our favor, it was 31 days before we notched 1,000 nautical miles out of over 3,000. Tommy and I were joined that day by hundreds of dolphins, and agreed that a swim with them was the perfect way to celebrate the milestone, even as late as we were getting to it, and give ourselves a much-needed bath. We must have underestimated our stench, because as soon as we took the plunge the dolphins vanished.

We discovered that roughly 40 percent of our food supply had spoiled, and our slow progress compounded the problem of not having enough to eat for the rest of the crossing. We couldn’t help but reflect on one of the comments my wife Beth and Tom’s fiancée Jodie had made during an interview before we left: “They’ll be fine as long as they have enough to eat.” Tom and I had previously discussed rationing, and though we desperately wanted to avoid it, we now had no choice. We worked out how much longer the crossing should take and divided our supplies by the number of days.

It was late in the crossing to establish the kind of routine that would give us the best chance of making it to England, but after we discovered the spoiled food we decided it was time we got organized. We stopped rowing together and settled on round-the clock 2.5-hour, solo rowing shifts. We also focused on our boat “culture.” We’d leave a hot flask on deck for the next person, and, when it was wet, do longer shifts to save us from both being miserable and reduce the amount of water in the cabin. We couldn’t expect to be on top of the world all the time, but with just two people onboard, managing emotions was crucial. We talked a lot, and one of our favorite pastimes was “Top Tens.” At first this was the usual stuff— influential movies, books, funniest moments—and then it turned to more philosophical topics—passions, people we look up to, and plans for the future.

provided by Israel Cannan via an onboard Go Pro

provided by Israel Cannan via an onboard Go Pro Rowing in tough conditions was risky as a lapse in concentration could easily result in catching a crab and taking an oar in the ribs or worse. The wind here was not yet blowing 30 to 35 knots, the point at which we’d generally clip in our safety tethers.

About a week after the first storm, we experienced another, and this time it was a direct hit. The wind blew 40-plus knots from the south for 12 hours, then at midnight it came in at about 60 knots from the north. The sudden change in direction played havoc with the waves, which rose to 30′ and marched in the dark from every direction. Tommy had been on deck at the change in wind direction, and when I relieved him in the early hours of the morning it was clear that he was physically exhausted and mentally rattled. He wanted out and I wouldn’t have been far behind him, but knowing we couldn’t actually get off the boat, we agreed to get some rest and then, like all members of the British Empire who find themselves in a crisis, we put the kettle on!

Anniversaries and birthdays passed by back home without us, and Tommy was desperate to get back to begin rebuilding his relationship; I sorely missed my three girls. But with the currents and particularly bad weather of 2015, the more we focused on the disappointing distance we had covered, the more psychologically harrowing the full length of the crossing became. Our journey was less a test of speed and more a test of endurance. This required a different mindset.

We talked about the few things that would put an end to the crossing, things like a man overboard, major injury, flooding the cabin, and running out of fresh water, which now had become a major concern. The decline in water quality from the watermaker was so gradual that at first we didn’t notice the increased salinity. Eventually I got stomach cramps and kidney pain, and inevitably crashed; Tommy did three rowing shifts back-to-back to cover for me. Our watermaker badly needed a service, and although we had the service kit, we’d lent its Allen key to a boat owner in Brooklyn and hadn’t got it back.

Tommy Hudson

Tommy HudsonPete takes a shift at the oars on the home stretch. After some long delays the sea anchor (in its red bag to port) was finally packed away and with roughly 600 miles to go, rowing never felt so good. With its high windage, MC leaned away from a crosswind, so leaving some gear on deck on the windward side kept the boat on an even keel. By this time our signs of hunger were becoming ever more visible.

Tommy nobly had me drink from the 120 liters of bottled fresh-water ballast while he persevered with the poorly desalinated water. It was a selfless act that I now suspect impacted Tommy far more than I appreciated at the time. With both food and water now heavily rationed, our crossing became even more a race against time.

Around 600 nautical miles from England we found ourselves on the wrong side of two high-pressure systems that produced easterly winds for 8 out of 10 days, and with food so low we had to change our approach to meals. Instead of continuing with our structured rationing system, we divided up all remaining food and resolved to eat no more than what we needed to get through the day. To make the food go further I only ate before a shift and would immediately clean my teeth to mark the end of each paltry meal; Tommy made a powder out of his remaining dark chocolate and he’d dip his finger in it to savor the taste. With dried beef in the greatest supply, we created unusual hot drinks including “Green Tea Beef” and Tommy’s favorite “Boffee.”

While the easterlies blew, with nothing to do but hang on the sea anchor we nicknamed this time “The Waiting Place” in recollection of Oh the Places You’ll Go, by Dr. Seuss. I created a verse of our own:

Waiting for the wind to change

To go around to a better range

Waiting for the rain to pass

Hoping that the tins will last

Buying time for bums to heal

Hands to thaw and feet to feel

Sitting around fighting cold

Praying that the anchor holds

With so little food and so far to go, we couldn’t risk losing the sea anchor. Without it we’d have no other way to combat adverse winds and could lose 50 miles in a day. For the first few days the wind blew at a constant 15 knots, but then it gradually increased to 25 and 30 knots, the strongest in which we’d used the sea anchor. With 6′ to 10′ waves coming over the bow and so much tension on the system, we made the decision to pull in the sea anchor and allow Mother Nature to send us backward at 2 or 3 knots. While this was one of the toughest decisions to make, it was the closest we ever came to letting go of our plans and ambitions and accepting whatever came our way with equanimity. We were now in the hands of fate flying along in the wrong direction, thinking we’d probably be 100 days at sea before reaching shore.

We got a text message over the satellite phone from Glenn McGrath, whose late wife Jane founded the cancer charity we were supporting, urging us to keep going. The easterlies eventually abated and we got a great run toward home. To go into the record books as an unassisted crossing we had to reach 5 degrees west, the Ocean Rowing Society’s official finish line, after which we could accept a delivery of supplies. Our colleague Simon Drayton set about trying to organize the delivery. A Cornish fisherman, Jimmy, and his crew agreed to make a detour to us on their way to their fishing grounds. My wife Beth and three girls, who had moved to Cornwall for the summer, dropped food canisters to Jimmy, but the effort was in vain. A storm kept them in port.

Tommy Hudson

Tommy HudsonFor two hungry men, cleaning a fish is a serious job. The throw cushion in front of the cabin door made it easy on our knees getting in and out of the cabin and also served as our kitchen countertop. A couple of cook pots melted circles in the covering.

On the evening of day 95 we received word of Jimmy’s delay and we were bitterly disappointed. On the dawn rowing shift after receiving the message—the morning of day 96, the day on which we would finally cross 5 degrees west—I went to the bow to retrieve one of the last bottles of drinking water, and came across the most wonderful sight. In the footwell of the rowing station was a 6″ fish delivered by the storm waves of the previous night. I was over the moon, and I immediately called Tommy out of the cabin to see what we’d inadvertently caught. Referring to divine intervention, Tommy said that at least He has a sense of humor! I cleaned the fish, cut it into six parts, quickly boiled it, and we enjoyed the most succulent meal of our lives.

Just before dusk, Tommy saw something on the AIS (Automatic Identification System) screen that we hadn’t seen in all our days at sea, a battleship. It was heading straight for us at 20 knots. He immediately radioed the ship and confirmed they were on their way to drop us a care package that would help get us home. Although we were absolutely thrilled at the prospect of having a proper meal, we were still a mile from reaching 5 degrees west, so we called Simon Chalk and confirmed that we could take the package without compromising the unassisted crossing as long as we crossed the line before opening the package.

The frigate HMS PORTLAND appearing out of the gray was a sight to behold. After being at sea for 96 days, I was so used to the two of us bearing the responsibility for anything that had to be done that I was working on a plan for the delivery. I asked Tommy how we’d coordinate it. He laughed harder than he had in days, and responded that in all likelihood Her Majesty’s Ship would coordinate us! The 436′ frigate left MC to starboard at a safe distance before deploying a rigid inflatable boat (RIB) with four personnel who were next to us in seconds. They gave us three large bags of food, two flasks of hot soup, and HMS PORTLAND caps, which we donned with pride. We thanked them profusely, and once the RIB was back on the battleship, its captain called on the VHF to say “Well done” and wish us a safe passage to Falmouth. We were impressed with the courtesy and generosity of the British Navy.

We packed the food down in the cabin before Tommy took to the oars in a very wet 35- to 40-knot southwesterly. Although it was uncomfortable on deck for him, with little energy between us left to row, it was the push we needed on the penultimate night at sea. After receiving the fresh supplies we knew we should ease back into food slowly, but this was easier said than done. Tommy was ravenous and ate seven meals in close succession before falling into a deep sleep.

Pete Fletcher

Pete FletcherFor the entire voyage, Tom had lamented having to survive without licorice and when the boat arrived to tow us from Lizard Point to Falmouth Bay, it brought a bag of his favorite candy. He was happy, and I was in peace!

Alone on deck at around 4 p.m., I looked over my shoulder and saw land for the first time in 97 days. At first I couldn’t remove my gaze for fear that it was an illusion, but then when I knew the sight was real, I was overwhelmed with joy and laughed aloud as tears rolled down my cheeks. With a full moon, clear sky, and 15-knot tailwind, the final night in the English Channel couldn’t have been better. The many boats and the flashes from the Longships and Lizard lighthouses were sure signs that civilization was only hours away.

In the morning we were very grateful to have a lift from the Deputy Harbormaster who towed us from Lizard Point up to Falmouth Bay, before releasing us to row MC to a waiting crowd at 10 a.m. on August 27. As we reached the dock, I heard Willow asking which one is her daddy and in the next moment my family was in my arms.

Nine months have passed since we stepped ashore, and perhaps Tommy and I did see what the crossing would make of us. Tommy feels like he was stripped bare by the ocean and all that’s left is potential that he can shape in any way he sees fit. He’s a new man and knows he can be anything he chooses. If there’s something that I learned, it has to be: Never set foot on an ocean-rowing boat again!![]()

Peter Fletcher is the Managing Director of World Challenge, a youth-development organization that enables high-school students to develop life and leadership skills through challenging student-led expeditions overseas. Although originally from the UK, Peter now calls Australia home and when not working overseas, he lives on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula with his wife, three daughters, puppy, and the family chickens.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Great story. We all dream of such a journey but very few take the chance. Congratulations.

Thanks Ron!

Got to say as a historian, I have to wonder what Harbo and Samuelson would have thought about the kit that is now needed to row across. They did have the advantage in their 55-day crossing [in 1896] of rowing a route that was well populated with shipping, and indeed took advantage of it for resupply after FOX was rolled over. Think that the Coast Guard would let you out of the harbor if you were trying to replicate it?

Good question Ben. Like you, I have a feeling the Coast Guard would have something to say about it.

Even with our modern gear, that was the other reason we took our opportunity to leave that night. Thanks for reading.

My only comment: Well done, very well done!