Snags and sudden shifts in the current came out of nowhere as we dodged left and right around dangerous gravel bars that shot water back and forth across the river. The shantyboat shook as the skegs bumped across rocky shoals. I didn’t want to think about what this was doing to the wooden hull.

I was at the helm, white knuckles on the wheel. “Freddie,” our 30-hp Mercury outboard, was trimmed barely in the water to keep the prop off the rocks, running at full throttle for a measure of control. My shipmate Benzy was at the bow urgently calling out hazards and depth; Hazel, the ship’s hound, cowered under the table. I was sure we would end up deeply stuck, if not seriously damaged or sunk. The river rocketed through a single twisted channel and took us along with it, slaloming the clunky shantyboat hard left and then hard right shooting us through a series of rock bars and snags, their jagged teeth raking either side of the hull.

This stretch of California’s Sacramento River was the sketchiest bit of boating I’ve done in a thousand miles and ten years of sketchy boating. We were shooting the Upper Sacramento River in a rustic wooden barge-bottomed houseboat. It was a boxy behemoth that had no place on this section of the river where sleek jet boats fly over the shallows.

Our re-creation of a historic shantyboat was similar to those that used to dot the banks in every river town on the continent through the early 20th century, the kind of houseboat built by workers and vagabonds who needed to live on the cheap. In that tradition, we built our shantyboat by hand, from the wooden skegs to the gable roof, using mostly reclaimed materials.

Redwood from a 100-year-old chicken coop, corrugated tin from an old outhouse, and single-pane windows pulled out of old houses contribute to a houseboat that looks like it floated out of a history book.

Where we started, the river had just barely come out of the rugged northern California mountains. The water comes from the depths of the Shasta Dam and is very brisk, warming as it meanders under the Valley sun.

Photographs by and courtesy of Wes Modes except where noted

Photographs by and courtesy of Wes Modes except where notedOur departure from Red Bluff was delayed by repairs to our outboard motor. Word about our stay near the ramp got out and we had a lot of visitors.

At the ramp in Red Bluff, just downriver from a now-decommissioned diversion dam, the river was really moving. We got to know this ramp well as we stayed there for two days trying to diagnose why our brand-new Merc motor wasn’t running. This delay was quietly frustrating Sara who collected audio of our repeated failure to start the motor and our colorful cursing. When we finally found Dave, the mechanic, he spent a few minutes and said, “You got water in your gas, chief.” It was an inauspicious start to a month-long journey.

When we launched, many people who know the river suggested we’d never make it, including the Fish & Game people and a series of fisherfolk. On the other hand, Dave and the local sheriff had more confidence in us. They told us the river was hairy but doable. Despite the naysayers, they were right.

It wasn’t all white-knuckle boating. Punctuated by these long moments of sheer terror and intense vigilance, we idled away the days in long floats of serene relaxation and contentment on the Upper Sacramento. As we floated south, the river slowed and took its time down the long Central Valley.

Though there are monotonous fields and orchards for miles on either side, the river corridor is wide and surprisingly wild. Birdsong formed the soundtrack of our days. Crickets filled the night, interrupted by the rustling of critters in the riverside jungle.

Having spent the night near the town of Corning, about 25 miles downriver from Red Bluff, we got ready to get underway again.

For a tiny rustic floating cabin, the boat is well-appointed. The barge hull is 20′ x 8′ with a 10′-long cabin. We have a small but cozy galley with lots of stores and running water, a big table for work and play, a leather couch largely dominated by the ship’s hound Hazel, a comfy sleeping loft, and a library of river history, art books, and trashy novels.

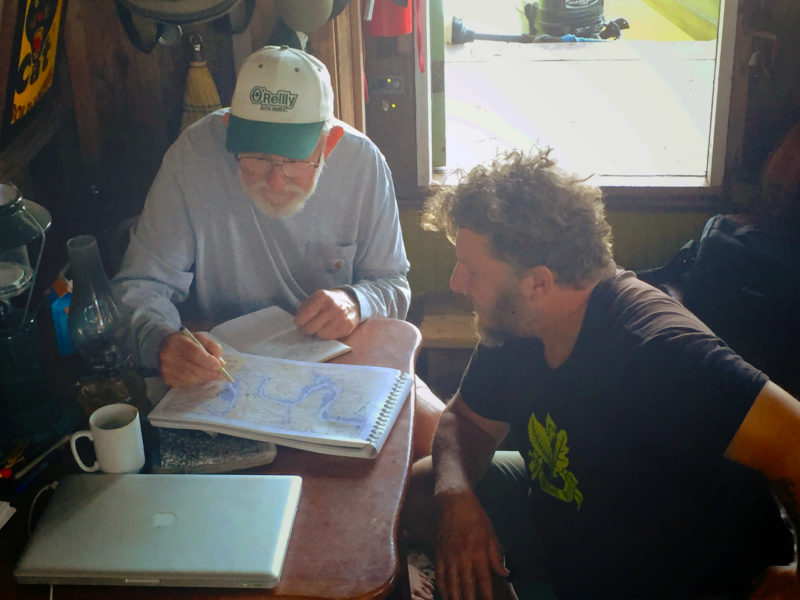

The visitors we welcomed aboard often gave us a wealth of local knowledge that we could add to our charts. We interviewed many of them to get their stories about life on the river.

I’m an artist by trade, and life aboard the shantyboat is part of my work for A Secret History of American River People, a project to collect the personal stories of river people. Every summer since 2014, I float down a major American river and talk to hundreds of people about vanishing river culture. Despite the dramatic moments on the shantyboat, we have plenty of time between piloting the boat and doing the oral history work of the project.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

After our days on the sketchiest portion of the Sacramento, we beached the boat at a pleasant sandy spot. We were not too far from a small town whose sleepy streets hide behind an impenetrable jungle and a sizable levee. “I’d kill someone for a sandwich,” Benzy said. So, we hiked into town on what I dubbed the Dustiest Road in America, winding through thick forest, picking blackberries and helping ourselves to grapefruit from a tree’s overhanging branches. After a sad little sandwich at Princeton’s tiny bodega, we headed back with 20 lbs of ice for our little cooler. “And for cocktails!” Benzy said.

A guy named Mike overtook us and offered us a dusty pickup-truck tailgate ride back to the river. This old fella lives happily in this tiny forgotten river town and goes down to the river every day with his dog, Gus. Mike is one of a vanishing breed of river people.

We whiled away the rest of the day with the tart bite of ice-cold gin and tonic, a meditative hour with a cigar, a float in an inner tube to cool off, a good book in the sun that turned into an afternoon nap, and a simple dinner. Jeremiah, another member of our crew, was meeting us in Princeton that night. “I brought a few things,” he said, gesturing at his mountain of supplies and gear. We got a ride from Mike down the long, dusty road to the shantyboat. We celebrated Jeremiah’s arrival with bourbon and cards late into the night.

With the skiff pulled ashore and the shantyboat tethered to the banks, our home for the night is bathed in the warm glow of kerosene lanterns.

In the morning, Jeremiah, always one to take care of the hard work first, insisted we do a water run. Jeremiah and I hiked to the road, foraging for water to refill our freshwater tanks—two long trips carrying two heavy, 5-gallon containers. While we were gone, Benzy picked a bucket of blackberries for a pie.

Mike arrived for an interview with a local friend, Al, an avid gardener, who gave us a huge bounty from his garden: fresh tomatoes, onion, cucumber, and squash. I am always surprised by the generosity of strangers when we are on the river.

People give us rides into town and loan us cars. They let us do our laundry and take hot showers. They bring us fresh fruit and vegetables, home-baked bread, books and articles, beer, and, of course, they share their stories.

I talked to Mike about his living in the little town of Princeton, population 400, his love of fishing and hunting, and his passion for the river. We talked for a couple hours, with Al chiming in with unsolicited comments and details that Mike had missed.

Mike set Benzy up for fishing with minnows and showed her how to bait a hook for striper. She spent the next several hours working along the bank. “Y’all like craydads?” Mike asked, “You know, crayfish? Like little lobsters?”

“Never had ’em,” said Benzy, “but hell, yeah.” Mike presented us with a whole trap-full of crawdads pulled from a secret spot in the river.

It was getting on dusk when Benzy yelled out that she thought she had a fish. She fought it to the bank and wrestled it in, a hefty 18″ striper. So, we capped off our long day of work and play with surprising bounty, a huge meal prepared in our tiny galley, and devoured around our little table: fresh fish, boiled crayfish, and blackberry pie right out of our janky, collapsible stove-top oven.

After a few rounds of cards, we tumbled into our racks. For Jeremiah, it was a sleeping bag on the deck under mosquito netting. Benzy and I retired to the loft in the gable of the cabin, up under the tin roof, rocked to sleep by the gentle motion of the river.

The next day, accompanied by the sublime aromas of good strong coffee, sautéed onions, garlic, and potatoes, we headed back out onto the wild river. We let the shantyboat drift quietly downriver, slowly turning in the swirling current. We listened to birds and watched the rugged landscape drift slowly by, always keeping one eye on the river for what it might throw at us next.

Mike Garofalo

Mike GarofaloThe town of Colusa is all but hidden by the levee that separates it from the river. Two water towers at the edge of town, towering above the trees, mark the best place to come ashore.

Over the next week, we left the wild river behind and Jeremiah left us to return to work. We were nearing Colusa, one of the few towns of any size on our journey. It was a chance to resupply, do our laundry, and a bit of maintenance on the boat.

The electrical system under the rear deck was giving us problems. Like an RV, the boat has two batteries, one for starting the motor and one for powering a few lights, charging phones, and other stuff. But unlike an RV, all the wiring was homemade and cobbled together over the years. The house battery wasn’t charging and I wanted to know why. So as Benzy made margaritas and floated in the tube, reading, I spent an afternoon under the rear deck sweating and swearing. In the end, the problem was the battery itself, which we replaced in Colusa.

With our aluminum johnboat, Benzy and I could leave the shantyboat on the river and make quick explorations of out-of-the way backwaters.

A TV news crew found us on the beach in Colusa and wanted to know about our boat and the project. The reporter stood onshore with the shantyboat in the background and made the inevitable Huck Finn comparison. We offered to take them out for a spin in the shantyboat and they made us do stupid tricks for the camera for an hour or so. Drop the anchor. Haul up the anchor. Repeat. I was reasonably sure the landlubber cameraman stumbling through the boat was going to end up in the river with his $10,000 broadcast camera. We were exhausted and relieved when the TV crew stepped ashore.

A guy who’d been following our travels loaned us an old pickup truck, so we had a chance to regain our land legs and cruise town in the evening, Credence Clearwater Revival blasting from the cassette stuck in the player. We stopped by a local watering hole, The Sportsmen, where locals were running amok on an otherwise quiet Tuesday night, dancing on the bar and loading up the jukebox with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers.

Mike Garofalo

Mike GarofaloLeaving Colusa, we caught glimpses of the Sutter Buttes, the remains of a single ancient volcano that are now known as the World’s Smallest Mountain Range.

After Colusa, the jungle shores gave way to rocky revetments, beyond which golden fields and dusty orchards extended into the hazy distance. For the first time on our trip, there were other people on the river, pleasure boats and families out for a dip on a hot summer day. Some boaters were curious about the shantyboat and zoomed dangerously close to us, throwing up a huge wake with their deep-V hulls.

The barge-bottom of the shantyboat is extremely stable as boats go, but big waves can still knock things about and break our teacups. With just a foot of freeboard, water comes over our deck easily. Each time it happens, we note, with anger, that neither etiquette, caution, nor good sense are requisite for buying a big, fast, expensive boat. We are very grateful to the boaters who slow for our little craft.

We found a rope swing from an overhanging tree on the inside of a slow river bend. We brought the shantyboat in to shore and took time for a leisurely lunch of tuna melt with Al’s fresh tomato. Against our mother’s advice we swam right after lunch, and the rope swing shot us off the high bank over the river to splash down in deep water. If we didn’t swim ashore quickly, we’d end up downriver with the current.

The mid-river scenery offered less variety, but afforded us opportunities to quietly drift downstream and even bob alongside the boat on a blazing afternoon. Benzy continued to fish from the boat with limited success. Along with more houses on the riverfront, we started seeing abandoned piers and docks…old boats sitting on the muddy bottom or high and dry on the banks. We were intrigued by these. What was their story? Where had they been? Who did they ferry? Why were they left to rot or rust? We would never know.

As we passed the mouth of the American River, Sacramento appeared with its Old Town district along the river. Suddenly, here we were in the Big City. The historic riverside section looked exactly as it had in 1890, if they sold taffy and Sacramento Kings T-shirts in the 19th century. Though chock-a-block with tourists, it still had its charms. There were several brilliant museums, including a well-known railroad museum, good restaurants, and lots of places to check out. Benzy and I were two river hobos out on the town.

That first night, we tied up at a dock under the Tower Bridge. Settling in for the evening, we played cards and read a book aloud, and then turned in, but soon the crazy began with party boats pulling up to the dock with fireworks, loud music, and people wandering the dock. It was a Sacramento Old Town Dock Rave. There was a knock on the shantyboat in the middle of the night. Who could that be? It was a sweet guy who followed our journey and had taken his boat upriver from who-knows-where to find us and welcome us to the area. Deep in the night, we were startled awake by the sound of something large and heavy crashing down from the deck of the bridge and slamming against the pilings.

Mike Garofalo

Mike GarofaloThe rusty corrugated roof might give the impression that our shantyboat came from an earlier generation, but it was built from reclaimed materials and had a patina of age even before it was first launched. On the roof over the stern deck are the bicycles we use to get around on land.

In the morning, we motored up the American River to see if we could find a quiet place to catch up on our sleep. A local park at the confluence of the American and Sac rivers is a popular place. Locals wade and frolic well out into the shallow water. Anglers anchor offshore with lines crisscrossing. We wove our way through the chaos. The waters of the American River are clearer and bluer than the muddy Sacramento, and since they come from melting snow in the Sierras, they’re colder too. Apparently, it is also a summer hangout for yachters. We discovered clumps of big boats rafted together full of partiers. There was a long line of boats rafted together gunwale-to-gunwale nearly across the whole river, an imposing yacht wall blasting Joe Walsh. Our shantyboat coming slowly upriver, looking for all the world like a floating chicken coop, did not fail to impress. We waved as the whole floating party appeared to check us out and politely declined offers to join the Yacht Wall.

Farther upriver, it was quieter. We were still in town, but the riverbanks were given over to wild and overgrown county parks. Oaks, willows, and cottonwoods shaded the banks. Thickets of elderberry and blackberries lined paths through the woods. There were folks squatting in little camps among the trees. Local kids were fishing, both young anglers with pro rigs and kids with makeshift strings tied to cane poles straight out of Huck Finn. We found a quiet bank in the sun, dropped a line in the water as well, and made coffee and breakfast of potatoes and cheesy grits.

We were near a rustic train bridge over the river and every few hours a freight train would woot over the bridge. We bathed in the river, Benzy played the banjo, and Hazel hunted ground squirrels tunneling in the bank. A couple putted by in a little boat and beached downriver. The fellow was sweeping a metal detector over the sandy bank. I talked to him for a bit.

Clyde was a treasure hunter and amateur archaeologist. He told us that he spends his free time on the shores of the American and Sacramento rivers hunting up treasures: old Chinese pottery and ceramic ware, metal bits and bobs from the Gold Rush era, and lots of bottles. “I have over a thousand bottles,” he said. “I’ve found every color—deep brown, cobalt blue, even old bottles that used to be clear, turned pink and purple by the sun.” In the short time I’d been watching him, he’d detected and dug up an old coin, an unidentified broken piece of speckled ceramic, and several rusty pieces of old iron. Clyde gave us the curious junk he didn’t want and we added it to our collection of odd river artifacts.

Another evening on the American River, we camped near a fellow in a neat compound a short walk from the shore. He was alternately sunbathing and organizing his camp. I had heard about the homeless camps along the American River north of town and was curious. The man’s name was Bar and he’d lived along the river for most of the last ten years. He shared a camp with another man who was getting on in years and needed Bar’s help. The local police knew Bar took care of the area and kept the “young bucks” out of trouble, so they told him that if he kept his camp clean they’d leave him alone. I sat down for a formal interview with Bar. His dark skin and bright eyes glowed handsomely in the sunset light.

He told me that about half of the folks who camped at the river were homeless because they struggled with mental illness or addiction, meth and alcohol being the most common. Bar himself had struggled with substances in the past and was clean now. “I feel for those people, but I don’t want to hang around them,” he said.

Benzy quickly took to fishing and got quite good at it. This 24″ catfish made a tasty and ample meal at dinnertime.

After our talk and some urging, Bar came over for a fish dinner at the shantyboat. He looked around and said, “Exactly right. You folks know how to live! Someday I’m gonna get myself something just like this.” Bar was a good neighbor, and we were sorry to say goodbye as we made way. I heard later that the cops had completely cleared out the camps along the river.

While we were in Sacramento, we exhibited the Secret History project with the Sacramento History Museum while docked along the Old Town waterfront below Joe’s Crab Shack. Hundreds of people braved the heat and came by to tour the boat and share their own river stories. One musician sat down with our banjo and played us a few old-timey tunes. Among the folks who found us there were a water-quality expert, a historian giving history tours of Sacramento, and a professional house restorer who offered to fix a cracked pane on the shantyboat and show us around town. Later, I interviewed these folks.

We needed to make one more stop in town to do a few interviews, and so Mark Miller, our new friend and window restorer, took us around to get groceries and ice. We stopped at Sacramento’s municipal marina where an apologetic attendant charged us an outrageous price to tie up for the night on an uncovered dock with no water and no electricity. Were we not so tired, we would have turned around to head back upriver to another marina.

Before we’d even had our coffee the next morning, we heard yelling. “Hey! Hey!” A lady was leaning out over the balcony of the swanky harbormaster’s office yelling, “Hey! This isn’t a public dock! You can’t just tie up there!” She was pointing at us. “You can’t tie up there,” she yelled.

From time to time, we’ve dealt with this kind of thing. We’ve had dockmasters say to our face, “You know, that’s not going to be welcome in any marina,” gesturing dismissively at our rustic boat. Fortunately, that’s the exception, not the rule. Most of the time, when marina staff discover our project and what we are doing, they refuse to let us pay.

This marina had lost our paperwork, and the woman working the office that morning thought we were squatting. We are certainly not above that, but we’d already paid too much for too little, and this lack of hospitality was over the top. We were still grumbling about it days later, joking in a screechy voice every time we docked, “Hey! You can’t tie up there!”

We were relieved to be out of the city. We had left the California capital, and the character of the river changed again. We had officially entered the Sacramento Delta, and we could feel it. The air smelled sharp and salty. The river got wide and sluggish and veered off into a maze of channels and sloughs. The sloughs had a different texture than that of the river. It was clear we were in a channel with rock revetment and high levees. A thin scrim of trees fringed the levee. At night it was ghostly and surreal.

We spotted old houseboats that we considered shantyboats, people living quiet lives—or at least weekends away—floating in unobtrusive corners of a forgotten slough. We never met anyone on these shantyboats and so we never learned their stories.

There were a good number of little marinas south of Sacramento that were little more than a few docks out in the river. Some looked posh, filled with big shiny yachts, and others looked forgotten by time. We stopped at one of the latter and found a collection of old houseboats and a legitimate shantyboat with a classic arched roof. The people aboard it said they’d had their boat in the marina for nearly a decade.

A cool swim was a welcome relief on a hot day at anchor. We had to keep a close eye on the river. If we weren’t careful and strayed from the still backwaters we could get swept downstream by the current.

We stopped for a swim and a walk along a levee in Sutter Slough where we discovered that the interior of the island was an endless expanse of pear orchards. We felt obligated to pick a bag of pears as part of our research. Hazel was relieved to stretch her legs on land, and picked up no less than nine ticks. Were all the slough islands infested? We were horrified, but didn’t encounter the bugs elsewhere.

I welcomed the rising sun after a quiet night on Sutter Slough. Kilts are well suited to summer travel aboard the shantyboat.

We heard that the nearby town of Courtland was having their annual Pear Festival, but small and large boats occupied every inch of available space on their public docks, most appearing not to have moved for decades. We attempted a tricky beach landing between trees in a brisk breeze. I was piloting and Benzy was trying to fend off hazards and set an anchor on shore at the same time. I got the shantyboat in an awkward position, and a big branch punched right through a kitchen window pane. We gave up on Courtland and headed downriver feeling stupid.

Our first stop on our Sacramento Delta tour was the town of Locke, a tiny town founded by Chinese who had helped build the railroad, then the delta levees, and finally worked as farm labor. This town retains its original rustic character and Chinese influence. Back in the day, Locke was a haven for bootlegging, gambling, and prostitution. An easy ride from Sacramento, it was where state politicians met to work out shady deals and let off steam. To be sure, it looks the same as it did in 1915 due to a century of neglect and poverty, a Byzantine net of historic preservation laws, and cooperative and occasionally conflicting ownership.

Mark came down from Sac to meet us for lunch. He immediately got to work on our broken window as well as ones that had been busted and covered for years. He introduced us to some of the folks in Locke, non-Chinese folks who’d befriended some of the original Chinese families and lived there for decades. My interviews included a photographer and oral historian who’d written a book about Locke.

As a Chinese community, Locke faces challenges. As the older generation of Chinese people die and younger generations move out of town, there are fewer and fewer Chinese people in Locke. The community viewed non-Chinese residents like Mark’s friends with suspicion until they slowly gained the trust of the community. Unfortunately, I never made a connection with any of the few Chinese families still living in Locke.

Docked near us was COMPASS ROSE, a former torpedo retriever, now a Sea Scout vessel with a crew of young mariners. Mark told us that he’d served in the Sea Scouts as a kid and plied the waters of the delta. Boy Scouts who reach high school can become either Eagle Scouts or Sea Scouts. The Sea Scouts are co-ed, a factor that helped Mark decide to join. He told us hilarious stories about his skipper, a hard-drinking Vietnam Vet and their ancient World War II ship. The crew of the Compass Rose gave us a tour of their ship from pilot house to engine room. We felt a warm kinship to these kids and all the nautical traditions they were steeped in.

Walnut Grove is 27 miles from the mouth of the Sacramento. This public dock is a good place to stop—it’s right across the street from a pizzeria, an ice-cream shop, and the cafe where we had breakfast.

Out on the river, the channels got wider and the reaches longer. The shantyboat was getting beat up by waves whipped up by the afternoon winds. Water sloshed over our decks, but our recently installed knee-knockers prevented waves from entering the door of the cabin. The tall shantyboat with its gable roof is a giant clumsy sail in a good wind. We resolved to get on the water earlier in the morning, but the call of a leisurely breakfast and several cups of coffee were always stronger than our sense of self-preservation.

Rather than brave the vicious winds of the Carquinez Strait to the San Francisco Bay, we opted to explore more of the Delta.

We chose a favorable wind and, from the Sacramento River, through a long cut, motored upriver on the San Joaquín. Vast reaches, long tidal flats, and insubstantial tidal islands covered in tule grass barely poking up above the water at high tide, gave the impression of a drowned world. With huge container ships moving both up and down river, we stayed out of the channel but the marshy levees afforded scant shelter from the wind. We couldn’t trust our NOAA maps. We were afraid we’d motor over an inundated island and stave in our hull on an old submerged fencepost. We were driving principally by instruments, navigating by compass, watching the depths on our electronic charts.

We stopped at a haphazard floating dock near some tumbledown fishing shacks to give Hazel a moment ashore and let us stretch our legs. On our short walk, the tide turned, putting us up-current from a menacing row of pilings and making getting under way more perilous than we expected. I started Freddie, and Benzy released the stern line. The moment she cast off the bow line and stepped aboard, I gunned Freddie before wind and tide could cast us into the jagged pilings.

We re-entered the maze of sloughs and silted-up cuts. This was the true delta, dotted with ancient marinas, secret coves, and endless tracts of tule-lined water.

Eleven hundred square miles of constantly fluctuating tidal and wind-blown wilderness. Our month-long journey had begun at the southern end of the Cascade Range, took us through California’s Great Central Valley, through the vast Sacramento and San Joaquin Delta, and brought us nearly to the sea; now it was time to bring an end to it. Consulting our maps, we liked the sound of Pirate’s Lair Marina just off the San Joaquin River. We spent a long afternoon carefully picking between tule islands and sprinting across long reaches, and landed at the palm-lined, green grass shores of Pirate’s Lair just in time for cocktail hour.![]()

Wes Modes is a California artist focused on social practice, sculpture, performance, and new media work. A Secret History of American River People is an art and history project, conducted over a series of epic river voyages, that gathers and presents the oral histories of people who live and work on major American rivers from the deck of a re-created 1940s-era shantyboat.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Wow! An epic adventure. I have a few rivers I would like to float; your Sacramento article reminds me of why I want to do it. Family obligations have prevented this so far, but there is always tomorrow. Thank you for a wonderful story and adventure. I love your boat!

Enjoyed! Thanks!

Excellent article, well written, and very compelling. Thank you!

Wes Modes’ Project is big and beautiful and essential to the watery heritage of our country.

GM and the Interstate have blunted our historical vision and have nearly extinguished our memory of a time when we were a three-ocean maritime nation blessed with an intricate, life-giving freshwater matrix of rivers and streams that carried Everything. Roads are relatively recent adjuncts to the millennia of thin-water transport on this continent. Highways appeared with the 20th century. Rivers were our interior connections. The adventures of steamboats surging up and down the Mississippi, Ohio, Hudson and Missouri Rivers beggars the cowboy cattle drives as adventure. Mark Twain saved a tiny remnant for us but the big story has yet to be written.

We’ve forgotten the enormous flow of river commerce. Strangely, we’ve nearly forgotten the technology that eclipsed river travel. After the Civil War, railroads dominated travel everywhere. We cross rusty tracks and marvel at occasional freight trains, forgetting the steam-powered, original railroad robber barons conning and playing the national economy like a piano, grabbing government funds like kids at a dessert buffet.

We have historical myopia, and we see living water as little more than a barrier to land travel. The lumber and stone that built the big eastern cities arrived by water. The bulk ore and coal and grain that fueled our Industrial Revolution arrived by ship and barge. The first steamboats plied the Hudson River. The Gold Rush came from California’s American River. Lewis and Clark pushed into the American West by way of the Missouri River and reached the Pacific on the Columbia River’s flow.

I was raised by the Ohio River in an industrial city, Wheeling, West Virginia. The River was filthy, treacherous, unpredictable, and essential to the growth of a muscular nation. Barges nosed up and down the brown water at all times of the day, They hooted through the night, stabbing searchlights, finding their channels. Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus arrived in later summer at Wheeling Downs Race Course by barge, floating downstream from Pittsburgh, its flatboats of equipment and menageries led by one of my memory’s most vivid artifacts: a steam calliope trilling and blasting from its own small barge, playing Sousa marches and old cakewalk stomps, every note piercing the ear and punctuating the air with a blast of white steam from its hundreds of note-whistles.

Wes Modes has a lot to tell about folks who still live on the rivers. Start recruiting apprentices, Wes! There’s much more adventure and mystery to unfold. As an historical writer my principle is simple and fascinating: all the good stories are real.

Hey Wes, how fun is to read about some of my old haunts outside of Chico. Having “tubed,” and partied on its banks in high school, taking inflatable boats down The River (in the local vernacular) and hearing stories of bass fisherman pulling 400-lb sturgeon out of its waters in the ’70s, I can only imagine how strong that river felt once you got on it. We all knew to respect it, the lazy look of it belies its power. What an amazing, ongoing adventure and how incredible to see it all from the rivers.

Man, you tell a great story Wes. Thanks

Good story. Rivers have long been a place for folks who don’t really mesh with the mainstream. My dad remembers the shantyboat community here in our Mississippi town. They made their money selling fish and freshwater shrimp and catching stray logs to sell at the mill. They all disappeared in the 1960s, but legend has it that the lower White River in Arkansas (not far north of our place) still has some river folk. It is illegal for them to live there, at least in the federal refuge, but several pilots I know who have flown over in the winter time say the shantyboats are not all gone.

Oh, come to Florida and do the Suwannee!

Jim and Pat

Over the years, we here in British Columbia have had far too many derelicts vessels left for the taxpayers to clean up the mess.

Although this is a Huck Finn adventure and fun to read, what happens if these floating homes become the norm in your waterways?

Wes, what can I say other than WOW. Your story gave me hope of a time long forgotten. I am a Viet Nam vet who was disabled and now in a wheelchair but that doesn’t stop me from reading your story then closing my eyes to imagine myself on a shantyboat floating down a river. Thank you for the few moments you gave back to me.

We had a similar (if not the same) sort of vessel at the previous wooden boat show in Hobart, Tasmania.

We live just west of where you left the river, in the town of Oakley. I’ve been to most places you’ve mentioned by boat and car; by paddle in my kayak closer to home. I could become a river rat and live in a houseboat or shantyboat. I used to know a couple of gentlemen who grew up in Oakley and on the river (Sacramento and the San Joaquin). One was a farmer and the other was a tugboat/river boat captain. More likely river pirates. I learned where things were dumped in the river, best sturgeon holes and striper fishing, and where the best blackberries grew. I will continue following your adventures. Stay safe.

I am also a sailor of rivers. I’ve sailed the waters of the Ticino and the Po rivers in Italy and have often rowed the Po from Pavia to Venice.

Very nice, this tale, truly impressive.

This is an adventure many of us dream of. Thank you for sharing your wonderful trip along with the great photos!

Thank you for your neat saga about your river voyage on the Sacramento. i also cruised my houseboat and patio boat for years up and down the river, with lovely long weekends on the American as sweet bonuses. It’s a wonderful life—thanks for sharing. Looking forward to more of your adventures.

The people who used to live in shanty boats on the river have been forced off the water onto rivers of concrete, parking their run-down RVs on out-of-the-way streets and parking lots.

Great story! We go out on the delta a lot. I live near marinas off 8 Mile Road, Stockton, California.

Great story Wes! Reminds me of Harlan & Anna Hubbard’s stories of Shantyboat Life and living at Payne Hollow which is on the Ohio River roughly between Louisville and Cincinnati. There is a group of volunteers working on the restoration of Payne Hollow to preserve Harlan’s artwork and stories of life on and near the Ohio River. Wes, have you finished your “Secret History of American River People” and if so where can I get information on it? Loved Jan Adkins comments also. Cap’n Tom