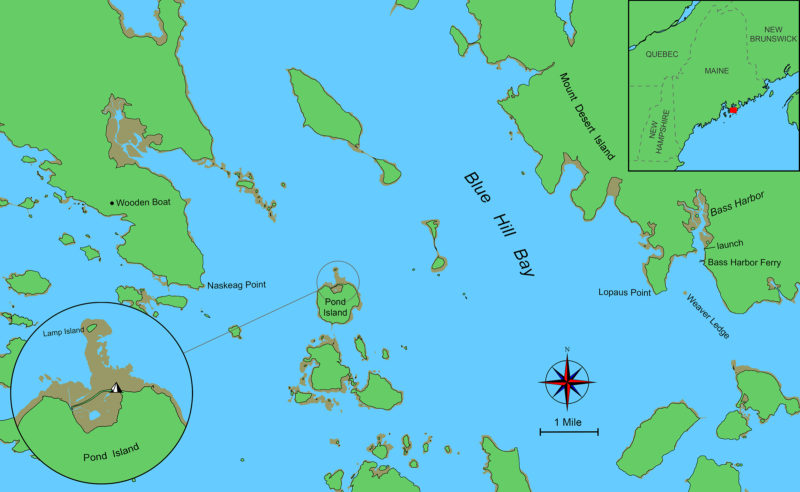

It was a Saturday morning in September, and my not-quite-girlfriend Delaney and I had just left the fishing dock in Bass Harbor on Mount Desert Island, Maine, in RIDDLE, my Shellback dinghy, for a weekend of camp-cruising in Blue Hill Bay. In spite of a late start—it was almost lunchtime—the morning fog, damp and breathless, had failed to burn off and visibility was measured in oar lengths instead of miles. With RIDDLE loaded down with two days’ worth of food and camping supplies, we floated the boat—sunk down well past the waterline—off the beach and headed out into the opaque white, using an aviation navigation app on my phone as our GPS.

Photos by Delaney Brown and Tom Conlogue

Photos by Delaney Brown and Tom Conlogue When Delaney loaded up RIDDLE, the boat’s paint was unscratched and our muscles were still fresh.

Delaney sat in the sternsheets serving as chief navigator; I was in the forward rowing station, and RIDDLE was cutting through the still water at a brisk clip when we heard the Swans Island ferry get under way somewhere off to our port side. The rumble of the ferry’s engines changed from a dull idle to a persistent growl, sifting through the fog and telling us it was in gear and under way. I grinned at Delaney in what I hoped was a confidence-inspiring way and pulled a little bit harder on the oars until I felt RIDDLE dig into her bow wave. The water quietly lapped along the hull as we pulled southwest, leaving astern the gritty beach and oil-slicked surface waters of the fishing dock shrouded in hazy gray.

Fresh off the beach with the fishing pier to port, I rowed out toward the fog bank as Delaney, reading off a flight-navigation app, guided the way.

While I had never launched here before, I thought I had a firm grasp on the water’s hazards and the standard ferry route. Bass Harbor is a cove that runs north to south with Weaver Ledge at its entrance just west of center. I had assumed that the car-carrying ferry, which left from a pier a few hundred yards to the south of our launching point, would stay east of the ledge, keeping to the deeper waters. Under this assumption, and in the interest of minimizing mileage, we kept to the ledge’s western side.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

With the ferry’s low hum nearly enveloped by the fog behind us I rowed ahead, confident in our course and that the ferry would pass well to our port side. Delaney, who had laid back and seemed to be enjoying the subtle rock and acceleration of each pull of the oars through the flat water, started to look around as if led by a hook in her ear. Hesitantly, she said: “I think we’re in the ferry’s path.” A half-minute later she repeated that, but now firmly. Though neither of us could see the ferry, the sound of the engines was rising to a crescendo, and I knew she must be right.

After a quick consultation of the chart, I turned hard to port and pulled for the ledge in the middle of the channel, using every bit of skill and muscle I possessed to propel us as fast as possible while listening to the ferry bearing down on us. Suddenly, the red buoy marking the west side of the ledge came out of the murk ahead, just as the ferry loomed from the fog 20 yards off our port beam. Suppressing a yelp, I made straight for the nun and we shot past it at hull speed as the ferry blew by, cutting a few yards from the marker on its way out the harbor. Quickly, I dug one oar in to spin us around, and we met its wake head-on, bouncing wildly and grinning like idiots.

Once the ferry had passed and our heart rates had settled to an acceptable level, we resumed our course and felt our way out around Lopaus Point, striking out westward into Blue Hill Bay. With the fog still closed in, muffling the sounds of the seagulls on the rocky shore until all was quiet, our world was soon contained in a circle of off-white nothingness, with only the occasional lobster buoy disturbing the scene.

We switched places, passing each other while stepping over coolers and dry bags filled with gear, and Delaney took over the oars while I reclined in the stern assuming a more managerial position. While she is an excellent sailor, having raced at a high level during college, this was only her second time rowing, so I got to enjoy the sight of a determined Delaney trying furiously to keep the oars in the oarlocks and our course a straight line. With laughter and a little not-so-helpful coaching as I pantomimed vague angles of oar blades and lever arms, we splashed our way west as the fog began to brighten around us.

After a half hour and about a mile of progress, we had just switched places again when I saw a pair of shiny dark heads bobbing in our wake. The seals stayed about five yards behind us as we plodded along at 2 or 3 knots, providing a welcome variation on the scenery for an hour or so.

By noon the fog had burned off over most of the bay, and the sun beat down on us without a breath of air to alleviate the heat. Stripped down to swimsuits, we rowed on impatiently and the 5 miles of bay between us and our destination seemed to stretch on indefinitely.

Pond Island is less than 3/4 mile across, is mostly tree-covered, and has a small tidal pond on the northern side that we planned to camp by. There is a 1/4-mile-long beach hiding this pond, and that spit of sand happens to be a popular picnic spot for locals, so I wasn’t particularly surprised when we rounded the corner and saw a white Boston Whaler pulled up on the beach with a flock of small children cavorting around it. The tide had carried us slightly south of the island on our passage over, so we turned north to get out of the current running parallel to the shore. We had been looking forward to jumping into the 50°F water to get away from the heat. Since we didn’t feel like socializing, we stopped rowing once we saw the beach was infested with youngsters and drifted slowly south with the ebbing tide, each of us sprawled on opposite ends of the boat too exhausted to be upright. Of course, this setback meant it was time to break out the beer and chips to help ease the pain of being cooked to medium-rare in the midday sun as small flies bit our ankles.

When the powerboat and its associated munchkins finally called it a day and vamoosed, we picked ourselves up and rowed over to the beach. The tide was almost fully out at this point, leaving about five yards of sandy beach above a hundred yards of rocky mud below, with scattered knee-high rocks sticking out at the perfect height to catch the propeller of a picnic-goer’s outboard at mid-tide. We grounded on the beach to the screech of plywood on rocks and dragged the loaded boat to the high-tide line. RIDDLE seemed to have grown much heavier while the biting flies stung like needles. Delaney and I made a frantic run to the water, with a comet’s tail of flies trailing behind us until we plunged into the water, the shocking cold of the emerald green a welcome relief.

After beaching on Pond Island, we took a quick break to take pictures and look around before the flies drove us into the water for a swim.

Once our feet were numb and the flies had subsided, we trekked back to the dinghy to unload and begin setting up camp. After about five minutes of searching, and stretching ourselves out to judge the ground’s levelness, we found a tent-sized flat spot in the knee-high grass above the beach and decided this was just the place to make camp for the night. It was shielded from wind to the north by an embankment at the top of the beach, and the ground was covered with rounded, sea-tumbled rocks and shells interspersed among them. We set up the tent, pleased with the views of Acadia Mountain to the northeast and Blue Hill Mountain to the northwest. The grass on the embankment hid the ocean, so it looked like we were in a field that stretched for miles.

By now it was only around two in the afternoon, and the sea breeze had finally started to fill in from the southeast. I grinned at Delaney, “Should we go for a sail? Maybe we could make it to Brooklin and surprise everyone.” She grinned back, “Of course!” So, we dragged RIDDLE back down the beach, although the haul wasn’t quite as far this time; the tide had just turned and water was creeping up the beach steadily.

I unrolled the sail, a standing-lug arrangement that fits inside the boat when stowed, and rigged the boat while still on the beach. Then, after a quick shove from shore, we began sailing north with the wind behind us blowing away from the island. Since the water just offshore was too shallow for the rudder, I had an oar over the stern for steering. With the daggerboard partially down, we scudded out past the last line of rocks and into deeper water. I pulled the oar back into the boat, letting RIDDLE luff up to head into wind while I set the rudder.

It was about 4 miles to Brooklin where Delaney is an editor for WoodenBoat magazine and I was on staff at WoodenBoat School, and we were hoping to blow in and surprise everyone that we had made it all that way in the fog. We settled onto a beam reach heading west, with Delaney wedged in forward by the mast looking very pretzel-like in the barely human-sized space while I sailed. I tried to concentrate on the sail and wind, doing my best not to stare at the beautiful girl lounging up forward. I can’t say I was particularly successful. Low, cotton-ball clouds built up over the mainland, the fog stayed in a solid bank to the south, and the breeze wavered at an inconsistent 4 knots as we worked our way west.

By the time we made it to Naskeag Point, the closest land on the western side of Blue Hill Bay, it was clear the breeze was dying quickly. We admitted defeat—our blistered hands had had enough rowing—and went to tack around to head back to Pond Island. RIDDLE came head-to-wind in the light breeze, but then faltered and fell back onto the port tack as we were barely making steerage way. Trying again, I pumped the rudder a few times to get the bow through the wind and we made a slow, languishing tack to port back toward camp. We made it back to the beach as the sun began to sink close to the horizon, and we hurriedly dragged the dinghy past the high-tide line and scrambled to find firewood. Delaney had brought a vegan pineapple curry she’d made for us to heat up for dinner. As a fervent meat eater, I was rather skeptical of a vegan meal, but, regardless of my food inclinations, we needed to hurry up and build the fire before the sun set. Delaney amassed a pile of driftwood while I made shavings from what looked like a promisingly dry piece of cedar and lit the fire; white smoke from the damp wood settled over the water like fine gauze.

The flames built up to chest height and sparks shot skyward like miniature rockets on an unstable trajectory. As the sun turned the western sky blood orange, we let the fire burn down to a bed of coals. We dug through the cooler, bypassing the breakfast food to get to the curry. I’d brought a wok from the boathouse at WoodenBoat, and once the flames subsided, I put it on the side of the fire with the exceedingly healthy-looking curry settled down at the bottom of it. After a few minutes, the curry was bubbling promisingly, and it smelled delicious, even to a diehard meat eater like me.

With the sun gone and the stars out, the driftwood fire burned steadily as it was fanned by the onshore breeze.

We had just dug into dinner with the ravenous hunger of a pair of young adventurers who had received too much sun for one day, when Delaney’s grandmother called. Since no amount of hunger should ever get in the way of talking with a worried grandparent, dinner was postponed until Delaney could assure her grandmother that we were indeed still alive and weren’t endangering ourselves too severely. After the phone call, we settled down for a few hours of storytelling and breeze-shooting as the wind began to build from the north and the tide crept up to lap quietly at the edge of our fire. With the sun long gone and the breeze blowing directly onto the beach with the urgent feel of a cold front, we snuggled by the fire in a Navajo blanket to keep the cold at bay.

Around midnight we ran out of firewood, so we decided to call it a night before we fell asleep on the beach with the sand fleas. We doused the fire and scuttled through the waist-high dune grass to the safety of the tent, our laughter carried ahead of us by the building wind.

The morning dawned cool and crisp, the kind of late-summer day that reminds you fall is coming. After languishing in the tent for about an hour, unwilling to leave the warmth of the sleeping bags, we crawled out of the tent around 10 to a stiff north wind flattening the coarse grass around the tent. Making my way to the site of the fire from the night before, I could still smell the smoke on my clothes and feel on my skin the grit of the sand still stuck there from the evening. I tracked down the single-burner propane stove and set it up on a driftwood tree trunk lying shielded from the wind behind the bank of the beach.

Acadia Mountain made our tent look tiny as we hid from the wind amid the grass.

We propped ourselves against the log and Delaney made us a breakfast of eggs and vegan sausage, which I had to admit was almost indistinguishable from the meat it was trying to impersonate. Sitting in the grass with the log pressing comfortably against my back, I stared at the salt pond 100 yards away. “Do you think we could get the boat in there?” I asked.

Waking up to bluebird skies and a crisp breeze, Delaney packed up the sleeping bags from the tent while I stalked off to the cooler bag to rustle up coffee and unpack what we were going to have for breakfast.

We ate an oxymoronic breakfast of eggs and vegan sausage. It proved to be an easy meal that paired well with instant coffee and pleased both the vegetarian and carnivore.

“We could row up the creek that feeds the pond,” she suggested, reading my mind and already packing up breakfast and moving toward the dinghy.

We launched RIDDLE into a steep, short chop crashing onto the sand. The spray salted my lips as we launched and sent shivers down my spine while I rowed us 20′ off the beach. Turning to port, we paralleled the shore, the beam sea trying to slide me across the thwart until we came to a cut in the sandbank with the creek that fed the pond. It was just wide enough for the oars to clear. We shot in with a following sea, and I pulled aggressively to keep us from getting thrown sideways by the breaking waves. Passing through the head-high cut in the bank, we were suddenly in the calm waters of the creek. The passage had gotten considerably narrower and soon there was not enough room for the oars. Seeing the perfect opportunity to impress Delaney, I asked her to switch places with me, then threw an oar over the stern to begin sculling us along. “Wait, let me try that!” she exclaimed.

If rowing had been hard to explain, it soon became clear that sculling was even more difficult. But Delaney was a quick study and was soon wiggling her wrist in just the right way to move us along, cursing colorfully every time the oar jumped out of the sculling notch in the transom. There is an advantage to learning to scull in a strip of water 5′ wide: the close banks let the boat pinball off them, so keeping a straight course isn’t much of a concern. However, the creek was made up of many short, 20′-long straight sections followed by 90-degree turns as it worked its way back to the pond, so just as Delaney got us up to speed, RIDDLE would ram into the bank and ride up onto the grass.

When not fending the boat’s bow off the bank, I “explained” sculling by flopping my hand like a fish. When not popping out of the sculling notch, Delaney laughed at my pantomime inevitably forcing me to fend off the bow again.

After a few such collisions, the stream became even narrower, and the dinghy was soon wedged between the grassy banks. As I stepped easily over the side and onto the grass, RIDDLE didn’t budge. The pond was only 20′ away, so once Delaney had piled out, I grabbed the breasthook and dragged RIDDLE the remaining distance over land, the skeg hissing as it cut through the grass. Once in the water, I triumphantly jumped into the dinghy and rowed the circumference of the 8/10-acre pond as the oar blades dragged on the shallow bottom. The pond wasn’t as spectacular as I had hoped and only about 5″ deep with shallows that persistently grabbed at the skeg of RIDDLE in an annoying way. After I’d made a lap, Delaney and I dragged the dinghy straight back to camp over the grass.

After successfully carrying RIDDLE the last 20′ and splashing down into the pond, it was time for a victory lap.

Turning back toward camp, I poled the first few feet with an oar before Delaney and I pulled the boat out of the diminishing creek and dragged it over the grass berm to get back to the beach.

By now it was about 11:30, so we decided to make one last excursion before heading back to Bass Harbor. Lamp Island, a hillock only 50 yards long and a third as wide, lay ¼ mile north of Pond Island’s beach. I have a penchant for high places, and this tiny islet seemed to be the tallest rock in the immediate vicinity, so we dragged RIDDLE down to the water yet again, leaving a trail of blue bottom paint on the golf-ball-sized rocks. Delaney jumped into the front before I could get there and told me she would do the rowing. We went bashing directly to windward, spray soaking our sweatshirts while whitecaps rolled past as we crawled toward Lamp Island. Making landfall on the lee side, I ran up to the sandy bank and climbed to the top. I pulled myself over the edge, but instead of the soft grass I had anticipated, the top was covered in exceedingly prickly bushes, and I was bleeding by the time I managed to stand up. Delaney laughed at my cursing as I made my descent but when I reached her, she consoled me with a kiss.

Delaney was reminded that rowing is actually pretty hard, and she popped out of the oarlocks a few times in the choppy conditions. However, we didn’t take any green water onboard and eventually made it to Lamp Island.

After relaxing on a half-tide rock on the north side of the island as the breeze kept the noonday heat at bay, we jumped back in the dinghy. The breeze was blowing an exhilarating 15 knots, more than enough to be downright sporty in our Shellback, and with the wind at our backs we flew back to Pond in about three minutes flat. Packing up camp, we threw gear loosely in RIDDLE in our excitement to go sailing. With Delaney on the tiller and me on the sheet, we tore off toward Bass Harbor on a beam reach, the water hissing on its way past. Doing 5 knots, RIDDLE threw cold spray onto us every time we met a wave, but we couldn’t stop laughing and were having too much fun to mind the cold. The fine water droplets hung in Delaney’s hair, adding silver to her auburn mane. The 5-mile passage that had seemed so long the day before flew by, and about an hour after leaving Pond, we had hardened up to a close haul and began tacking north up Bass Harbor.

With spray flying and sprits high, RIDDLE made excellent time back toward Bass Harbor on a beam reach.

Once we were inside the protection of the harbor, the breeze became fluky, and sections of calm water were darkened by catspaws barreling down from all sides. The winds converged on us in a frustratingly inconsistent manner. It took us the better part of an hour to work up the mile of harbor, but we eventually ran up on the beach by the fishing pier we had left from. RIDDLE protested loudly as we ground onto the barnacle-covered rocks, and we climbed out soaked in seawater and once again gritty with sand. Our adventure had come to an end, the two of us none the worse for wear and RIDDLE losing only a little bottom paint. We packed the boat into the back of my truck, and with sand clouding the rearview, my girlfriend Delaney and I peeled out in search of food and a shower, muscles sore but spirits high.![]()

Tom Conlogue is a former WoodenBoat School waterfront staff member who is currently feeding a crippling boat addiction as a student at Maine Maritime Academy. He can usually be found near some patch of water messing about in small boats.

Editor’s note: Pond Island is administered by the Maine Coast Heritage Trust and camping is permitted only at the established site on the east side of the island. The author learned of the restriction only after the trip.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Nice story. When I read this, in my fresh 60s, I would like to be young again. My (our) voyage of this kind was on the French river Arroux, about 1990.

So far it’s already inspired a few more adventures. Hopefully you and your partner will also have more adventures to look forward to.

I bet that ferry capt. had a few choice words!!!!!

A couple of wonderful adventures in one small boat!

Great story and adventure and all at minimized equipment, etc. We who navigate larger vessels from time to time link you with kayakers so far as fog is concerned; we may refer to you as speed bumps!

Not funny. Stay safe. We all look forward to many more sea tales from you two.

A beach “infested” with “munchkins”? If you keep going on these romantic trips you might find that is you in a few short years!

The part about getting wedged inshore reminded me of one of my earliest memories. My dad and I built two Sea Shell prams from a kit ($35 each!) in the late 1950s. They were a product offered by the Hagerty Furniture Company who also offered kits for the 110 Class racing sailboats at one time. There was a summer event called The Pirate’s Race. Each boat was outfitted with three tennis balls. If you could throw a tennis ball into another boat you “captured it” and they had to return to the beach. The last boat afloat won. A friend and I sailed our little sailing pram well up into one of the marsh creeks, threaded our way into a drainage ditch and dropped the mast. We reasoned that no one would either see or reach us by the end of the day. But we didn’t allow for the outgoing tide and ended up high and dry, marooned there until almost dusk. It was a lesson I learned early and won’t forget mainly due to all the mosquito bites.

I want to camp on Pond or Marshall this coming summer with my sailboat and I was reading this story and realized it is Tom and Delany who helped teach me to sail! Hi you guys! Great story, great adventures!! See you next summer.

Heather