The David Stimson–designed Ocean Pointer, a 19 1⁄2′ center-console outboard skiff, stands on the broad shoulders of a long Maine tradition. Alton Wallace began designing this boat’s ancestors in the 1940s, settling on the legendary West Pointer hull form in the mid-1950s. The West Pointer was meant as a stable fishing boat with good seakeeping abilities. He arrived at the hull shape the old-fashioned way, which is to say that he carved its shape in wood rather than drawing it on paper. Wallace built hundreds of these skiffs himself, and had a reputation for unusual generosity with the design: hundreds more—perhaps thousands—were built by fishermen and by other shops in both wood and fiberglass. Some of these were direct copies of Wallace’s original lines; others were derivative designs.

Although so many boats were built over several decades, the boat’s lines were not formally committed to paper until 1996, when the Rockport (Maine) Apprenticeshop measured one of Wallace’s boats, drew the lines, and built a copy. Bob Miller, writing for WoodenBoat No. 130, recalled the days in which he got to know Alton Wallace during that measuring project. “One might ask,” wrote Miller, “how someone with just a block of pine and a jackknife could design a boat that has been so widely copied and imitated. The answer is simple. Before Alton started whittling out the shape of what was to become the West Pointer some 50 years ago, he had spent a good part of the previous 30 years in and around boats that he and his father built and then used for trawling, dragging, shrimping, lobstering, and tuna fishing the often unpredictable waters at the mouth of the New Meadows River. Alton knew what made a boat work and what didn’t.”

Matthew P. Murphy

Matthew P. MurphyOwner-builder John Blatchford with his Ocean Pointer skiff near Bucksport, Maine. Using detailed instructions from designer David Stimson, Blatchford built the boat over the course of two years.

“It’s a flat-bottomed, round-bilged boat,” Paul Lazarus told me. Lazarus, who edited Professional BoatBuilder magazine for nearly two decades, owned a 16′ Alton Wallace skiff. The 16-footer was Wallace’s original design. He then built an 18-footer and, later, a 20-footer by simply spreading the molds apart and padding them out—all by eye. The larger boats eclipsed the 16-footer in utility, but the 20-footer was too big for Wallace’s shop—a converted schoolhouse. The 16′ edition of the West Pointer—a tiller-steered open boat— was powered by a 25-hp outboard. The 18-footer, with its greater length, side decks, a bulkhead, foredeck, and center console, was heavier and required twice that power. This boat—the 18-footer powered by a 50-hp motor—was the oft-copied sweet spot.

The hull form became famous for its good attributes, and especially for its great stability at rest. “That’s why it was such a good work platform,” Lazarus said. “They could drape a giant tuna [a 300-plus-lb fish] across the gunwales without rolling the skiff.” The boats were also low-sided for easy working and, with their flat bottoms, quick to plane. Pronounced sheer and flare forward obviated the need for a spray rail forward, and this shapely bow was balanced by proportionally pronounced tumblehome aft.

“If Wallace were to be faulted,” Lazarus said, “it would be because he didn’t prime the faying surfaces.” His boats were dry-strip-planked, which means that the planks were mechanically fastened without any compound or adhesive between them. “The only compound he used in the boat was where the keel met the stem—some black goo,” said Lazarus. His own 16-footer lacked floor timbers and had a shallow keel, and thus had a fairly limber bottom. “It was underbuilt,” he said. He is quick to point out, though, that the quickness of Wallace’s builds was in keeping with the design’s purpose: “He didn’t build these boats to be rebuilt; he built them to be used up. They were workboats.”

As workboats, dry-strip-planked West Pointers were meant to be used often, and were certainly not meant to spend long stretches out of the water, living on a trailer. The strip planking would dry and shrink in these conditions, creating numerous leaks that would seal only in the days following relaunching. And these boats were fastened with galvanized nails, which tended to rust out.

So, here we had a beautifully evolved hull form of serviceable but limited-life workboat construction. The West Pointer would make a fine form for a recreational boat, but this would require a construction upgrade.

Enter, David Stimson and the Ocean Pointer.

In the Ocean Pointer, Stimson channels Alton Wallace’s intent for the West Pointer, but he updates the construction to take advantage of epoxy. In his book, How to Build the Ocean Pointer (WoodenBoat Books, 2002), Stimson writes, “There is nothing new about the elements of Ocean Pointer’s design or construction. The general hull form has been around for at least fifty years. Plywood bulkhead frames, strip planking, sheathing fabrics, and epoxy have been in use for decades. The combination of these elements is what makes Ocean Pointer unique. Someone may prove me wrong, but as of this writing, I think that this is the only design that incorporates epoxy-glued strip planking on bulkhead frames in a pointer-style hull.”

Matthew P. Murphy

Matthew P. MurphyOcean Pointer uses a classic center-cockpit layout, with ample storage under the foredeck, in the console, and under the helm seat

To get a feel for the Ocean Pointer, I went on an outing with John Blatchford, who built a fine example of this boat. Blatchford’s boat is built of strip-planked juniper formed around plywood bulkheads. The backbone is of mahogany; the stem assembly is laminated. That assembly includes an inner stem that does the structural work of holding the boat together forward; an outer stem, or stem cap, creates the illusion of a rabbet without the labor of cutting one. This is a common technique in strip-planked canoe and kayak construction; it makes good use of materials and is accessible to the inexperienced boatbuilder.

A plywood sole sheathed in Dynel caps a water-tight bilge, making the boat self-bailing and contributing a vast, foam-filled reservoir of buoyancy. The ample foredeck and small afterdeck are also of Dynel-sheathed plywood. In a departure from the instructions, Blatchford fiberglassed his boat both on the inside and outside. “I wanted a bulletproof boat,” he says. He also ran the sheer about an inch and a half higher forward than the design specifies, thinking it might knock down more spray. After some experience with the boat, he concedes that he wouldn’t advise either change. “It would have been a bulletproof boat regardless,” he says.

Working with the assistance of Jim Kingan of Penobscot, Maine–based Rosebud Boat Works, Blatchford built his boat over the course of two years. He has high praise for Stimson’s instructions, which he used before they were published as a book. “It’s a great book,” Blatchford says. “Great instructions.”

Blatchford powered his Ocean Pointer, OLD TIDES, with a 50-hp Yamaha four-stroke. He’s kept copious notes on the boat’s performance, and shared these highlights: At 5,300 rpm with only the operator on board, the boat will make 28 knots. Drop to 4,000 rpm, and the boat slows to 16 1⁄2 knots. With three people on board and the motor running at 4,100 rpm, the boat makes 15 knots.

OLD TIDES handles well at low speed, with little tendency to blow off sideways despite her flat bottom sections. She transitions gently onto plane and makes a nice, easy bank in hard turns. There’s none of the suspicion of tripping we’d feel in a chine hull pressed into a too-hard turn. Accelerating to full throttle, she gradually presses her bow further and further down, finally running level at 28 knots.

Blatchford showed me his boat in the sheltered waters near her home port of Bucksport, Maine, near the mouth of the Penobscot River. We didn’t have a chance to test the efficacy of the boat’s shapely forward sections in keeping the occupants dry, but that’s of little consequence to Blatchford: “If it’s a windy day,” he says, “I’m not going out on [Penobscot] Bay.” Lazarus, however, told me that the boat was well mannered in a chop and didn’t root in a following sea.

Blatchford uses his boat mostly as a river cruiser, exploring the marshy narrows of nearby Frankfort Flats, or making the scenic run to Bangor, about 15 miles to the north. It seems a perfect fit for him. I asked whether he’d considered other boats when selecting a design to build, and he said that he did not. The West Pointer’s reputation cinched the decision for him early. “I took two years to build the boat,” Blatchford says, “and I enjoyed every minute of it. It was a great joy. Great joy.” ![]()

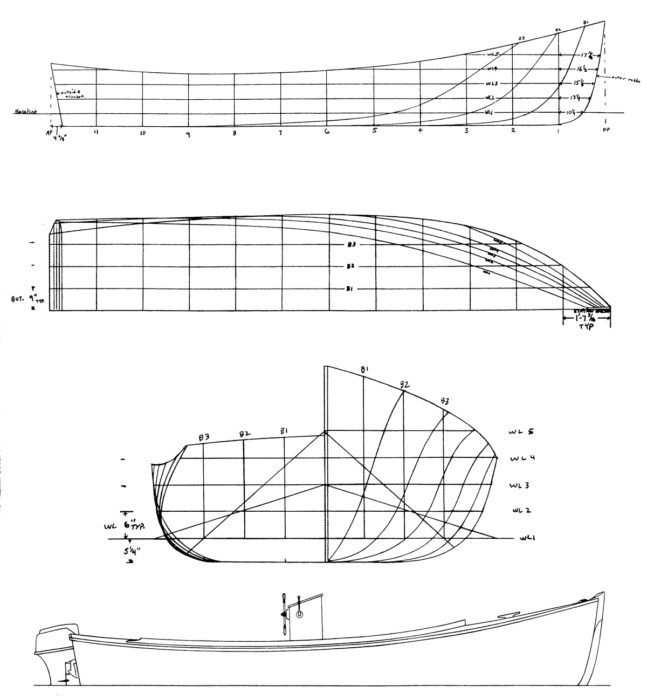

Ocean Pointer’s hull shape derives its distinctive features from the skiffs built by Alton Wallace since the 1950s. The distinctive features are these: ample flare in the bow sections, pronounced tumblehome aft, and flat floor sections running along a dead-flat keel profile.

Plans for the Ocean Pointer are available from Stimson Marine. The instructional book, How to Build the Ocean Pointer, is available from The WoodenBoat Store.

Have any members on this site built this boat? I’m currently building one and I’m curious how people got along with the build and the finished product. Thanks

I didn’t see any reply to your question on the Alton Wallace 18. Are any of these boat strip planked, edge glued, and fastened and not fiberglassed—simply sand and paint?

I used to be a fan of strip planking, but now feel its too time consuming. Like planking with spaghetti. Glueing between planks is worse still. Using epoxy as the glue and trying to sand fair is near nightmare. Sheathing in fiberglass and then trying to make that ripple-free is also harder than amateurs realize and one more time-consuming step in what will seem like a dark tunnel. But dry planking with the widest planks you can manage to use- leaving an outboard open bevel in the seams of like 10 degrees to fill with sandable epoxy (I use glass microspheres to toothpaste consistency) and all simply faired and painted in honest fashion is my choice now. You can use a sandable epoxy final primer before 2 or 3 coats of paint to protect and stabilize the planks, but fiberglass is not necessary. It will last as long as you take care of the boat. The epoxy primer will make the paint outlast historic methods. Same with the interior- or use penetrating epoxy in the bilges before painting with a catalyzed paint. Again, no need for more fiberglass. People need more appreciation for honest historic simplicity.