Our house overlooks Irondequoit Bay, which opens into Lake Ontario near the city of Rochester, New York, and for a couple of years my wife, Carol, had been expressing a desire to have a powerboat. We already had five boats of various sizes—two sailboats, two canoes, and a kayak—that I had built over the previous 16 years, but they were all too small to be kept in the water and required time and effort to haul to a launch ramp and set up for an outing. There is a small marina below us on the bay, and Carol’s dream was to have a powerboat we could keep moored there so that any time we wanted, we could walk down to the boat, climb in, and go for a ride. She was quite happy to buy something, but I, of course, said, “Oh, we don’t need to do that, I’ll build you one.” That rash offer led to a three-year project.

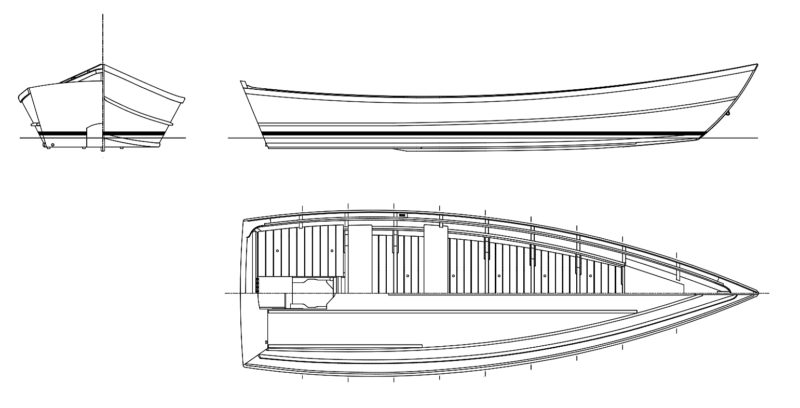

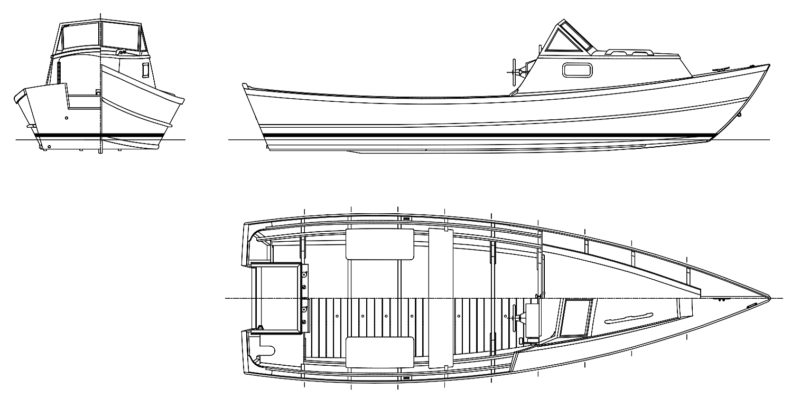

My choice of design was determined by the size of my basement workshop and its French doors. I decided on the Nexus 21′ Planing Dory, designed by David Roberts of Nexus Marine in Everett, Washington, which was the largest boat that I could get out of my basement. I ordered the plans, which include drawings for the dory with a cabin and a transom-mounted outboard, and for the open boat with a motorwell. A construction drawing is numbered and cross-referenced with a 12-page construction guide. A table of offsets is available—in feet-inches-eighths, Imperial decimal, and metric—for builders who’d like to do the lofting. Those who’d like to skip the lofting can order full-sized Mylar patterns for the frames, stem, and other small parts. A person with some boatbuilding experience should be able to build this power dory with this comprehensive plan set.

Andrew Kitchen

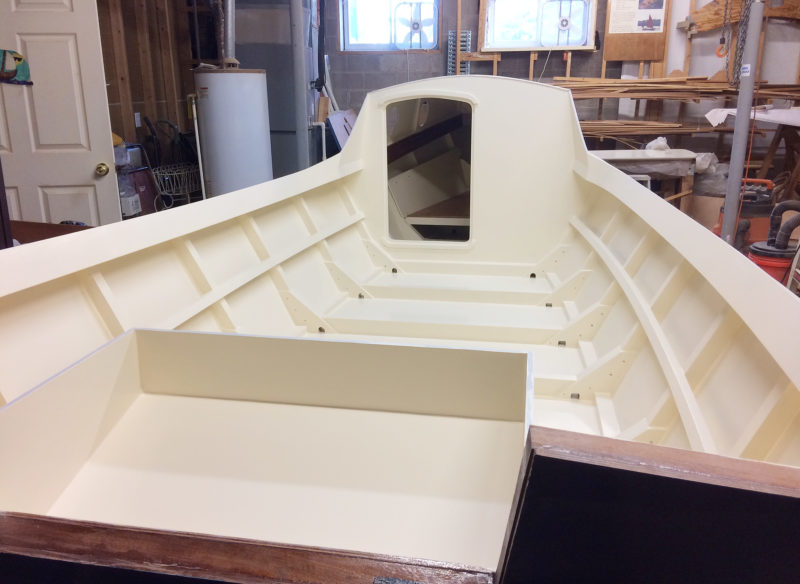

Andrew KitchenConstruction of the straight-sided Planing Dory is not complicated, although the framing does require some skills that first-time builders may find unfamiliar. The plans give detailed instructions for the build, especially regarding the substantial framing from which the dory gets its strength. However, the interior layout is less specific, allowing builders to make their own design choices.

The boat has slab sides of 9mm plywood and a flat 12mm bottom, so in many ways it’s a straightforward job, not much more demanding than carpentry. Unlike the boats I’ve built before, this one depends on substantial framing for its strength. The frames need to be beveled, something I didn’t have to worry about with my other boats, which had all been built around molds. I lofted the hull before starting the build, so I was able to lift the bevels directly off the lofted lines and pre-bevel all the frames before assembling them and setting them up on a ladder frame. The beveling was simple because with a slab-sided hull there is not an appreciable change in the angle along each limb of the frames, and the minor variations can be dealt with once the frames are in place on the building form.

The plans suggest 1-1⁄2” vertical-grain Douglas-fir for the framing, but it is hard to come by in good quality here in upstate New York. I chose sapele because it was locally available, affordable, and takes epoxy well. Mahogany was too expensive, and I was leery of using white oak—I had read warnings about using standard epoxies with it. I was happy with sapele but, like many hardwoods, it will bind and snap screws if the holes are not carefully prepared and the screws lubricated. All fastenings in this project were 316 stainless steel, as suggested in the guide.

The recommendations in the plans for construction are well thought out. I was particularly impressed by the measures taken to eliminate opportunities for rot to develop in the finished boat. For example: each frame consists of three straight futtocks butted together with epoxy and reinforced with 12mm-plywood gussets screwed and glued to both sides of each joint. The gussets bridge the inside corners of the frame, and the pockets created are filled with carefully shaped wedges of hardwood, eliminating a place where water would be prone to collect.

Andrew Kitchen

Andrew KitchenThe small cabin allows passengers privacy when changing and, with its semi-V-berth, somewhere cozy and comfortable to relax. A head may be installed at a later date.

The boat is built upside-down on a ladder frame. The construction is straightforward. The only challenge I found as a solo builder is the sheer weight of the bottom. I used 1⁄2″ sapele plywood as recommended by the plans, and this involved three 4′ × 8′ sheets. Luckily, two I-beams run across the ceiling of my workshop, allowing me to install two chain hoists; they made lifting and positioning the bottom easy.

I covered the exterior of the hull with 6-oz fiberglass cloth and epoxy. The plans call for a 1-3⁄4″ x 2″ oak skeg and 3⁄4″× 1-3⁄8″ oak skids bedded with 3M 5200 sealant and screwed through to the frames. I painted the hull before turning it over, starting with a two-part epoxy primer, followed by a linear polyurethane topcoat and a water-based bottom paint to minimize vapors (my workshop is directly under our bedroom). Over the last four summers the topcoat has held up well. I scrape down the bottom paint and refresh it each season. Our local waters are not the cleanest and the dory’s waterline acquires a thick layer of scum, but otherwise the bottom stays remarkably clean.

Once the boat was right-side up, I cleaned the inside, put fillets of epoxy along every seam, and spread two coats of epoxy over the interior. Up to this point I had followed the design to a T. The Planing Dory was designed as a versatile craft that would adapt well to many uses on the Washington State coast. Some builders finish the dory as an open boat with the outboard either mounted in a well or on the transom. Others add the cabin and windscreen detailed in the plans to protect the crew. My goal was to build a boat for use motoring to a beach for swimming or to a waterside restaurant on our local bay on New York’s Lake Ontario shore, so I made some modifications to the design. I reduced the height of the cabin and gave the windshield a more streamlined look. I also added a deck and coaming around the cockpit to soften the lines and protect passengers from spray.

After framing the cabin and side decks, I painted the interior before adding the 3⁄8″ okoume plywood cabin walls and 1⁄4″ okoume decking. With the major construction finished, the trim, windshield, and cockpit furniture remained. This part was challenging but fun. I had free rein as far as design was concerned: the plans leave interior organization to the builder, recognizing that the uses to which the basic hull can be put are as diverse as the people who choose to build it.

My aim was to build a versatile day boat. The cabin has an upholstered semi-V-berth, with room for someone to change into a bathing suit in private. No head or porta-potti has been installed at this point. The cockpit provides seating for six people. The accommodations were finished bright with a water-based TotalBoat Halcyon Marine Varnish.

Andrew Kitchen

Andrew KitchenAt 21′ LOA even the cabin-version of the Planing Dory has a roomy cockpit, spacious enough for six people. With lockers beneath the bench seats and the open cubbies under the two forward seats there’s plenty of storage.

It had taken me just a couple of months shy of three years to get the boat essentially finished. I still had to install the steering mechanism and an electrical system—a new experience for me. I left the installation of the 40-hp Honda outboard to the dealer.

Carol Kitchen

Carol KitchenWith the cabin, the dory can be a comfortable cruiser. The plans include drawings for the dory as an open boat with the motor moved forward into a well, a workboat option suitable for fishing, scuba diving, or hauling.

Early in the spring of 2018 the boat was finished, and ready for the engine installation. That summer we were off to Mystic, Connecticut, for The WoodenBoat Show and a vacation on Masons Island, south of Mystic. After some maiden trips north on the Mystic River and south to Fishers Island Sound, our little craft now sits in the marina below our home.

Owning a powerboat has been a new experience for me—my previous experience had been exclusively with oars, paddles, and sails. Learning to dock the boat was the steepest part of the learning curve. Fortunately, the dory is a sturdy little craft and has handled the punishment with aplomb. The flat bottom provides reassuring stability, a benefit when it comes to carrying people with little experience of boating. I have recently added a bimini, which provides shelter as well as a handhold when coming aboard.

With the usual complement of just the two of us aboard, the dory’s performance is quite lively and remains so with four aboard. I’ve taken as many as five passengers; with six of us aboard, acceleration and top speed are predictably reduced. The flat bottom does pound in a chop, particularly in water disturbed by the crossing wakes of high-speed powerboats. Carol and I are not into speed, so we usually take the dory out in the evening when the traffic has thinned and slowed and the bay is peaceful. When driven hard, the boat does throw up a bit of spray, but not an excessive amount. It carves a turn well and doesn’t skid; in our confused waters I don’t push too hard to avoid the risk of the boat tripping over its outside chine.

Carol Kitchen

Carol KitchenThe author’s dory is powered by a 40-hp outboard, well within the range of 25 to 50 hp recommended for the design. The top speed listed is 25 knots.

Flat-bottomed boats can lack directional stability in a head- or crosswind until they have some way on. There is not much lateral resistance up forward to hold the boat on course, especially with a cabin in the bow adding to the tendency to weathercock. We get stiff breezes in our area, and a couple of times the bow has pivoted downwind as I was leaving my slip. Backing into the wind provides the maneuverability required at low speeds in tight quarters until I have enough space to turn and get up to speed.

The Nexus Planing Dory has expanded our boating horizons and provided some wonderful experiences for Carol and me, our family, and friends.![]()

Andrew Kitchen grew up in England in the 1940s and ’50s when the only boats he knew were wooden ones. He used to devour his grandfather’s yachting magazines; his favorite parts were the centerfolds featuring the lines of the latest ocean racer or cruiser. He didn’t understand them completely, but they held him mesmerized. In his teens Andrew sailed on the Norfolk Broads with a school sailing club and day-sailed in the English Channel with his family. A half-century later he retired from a career in teaching mathematics and computer science. His first project was to build Iain Oughtred’s J II Yawl, the forerunner of the Arctic Tern. He then averaged one new boat every three years. His current project is Doug Hylan’s Siri, an 18′ canoe yawl. It’s a version of the Iris, which first caught Andrew’s eye 12 years ago when he saw its drawings in W.P. Stephens’s 1898 book Canoe and Boatbuilding.

21′ Nexus Planing Dory Particulars

[table]

Length/20′ 11″

Beam/6′ 9-1⁄2″

Draft/6″

Dry hull weight/500 to 1,200 lbs

Power/15 to 50 hp

Speed/12 to 25 knots

[/table]

Plans for the Nexus 21′ Planing Dory are available from Nexus Marine Corporation for $125. Full-sized Mylar patterns are available at an additional cost.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I built a similar 19′ Texas Dory skiff with a built in motor well with a splash baffle. No cabin, rowable, sail rig also. Powered with a 25 hp outboard. Many fishing and family trips. Shallow draft nice for beaching, dry, lightweight too. Wind on freeboard ratio gave me a little issue, but bottom line a lot of boat for my first build. West epoxy did very well. Should have never sold it

Lovely work, Andrew! Thank you for publishing this. The Nexus is a design I have day dreamed about for similar uses as you are putting yours to. Very elegant in a form-follows-function sort of way. It is good to see such a nice example, and to read your impressions of her in use. Well done!

Thanks John for the kind words. They are much appreciated coming, as they do, from one whose high boatbuilding standards I very much admire.

Andrew

Andrew, she is stunning yet seems to provide great utility. Not being into speed, are you pleased with your power choice? Do you stick to the bay or venture out along the coast a bit (writing from Rochester as well), does she handle Lake Ontario well on an appropriate day? I can envision a jaunt to Charlotte, Pultneyville or points further on.

I have taken short trips along the coastline, both to the east and to the west of the bay. She can handle moderately rough water very well but like any flat-bottomed boat the ride is not always comfortable under such conditions. This is most noticeable in crossing the short wavelengths of powerboat wakes as opposed to the longer wind-induced waves of the open lake. My approach is to ease up on the speed a little.

As far as power goes, 40 hp is plenty for my needs. If you consistently take on a full complement of passengers and want get up on plane, you could increase the power a little. However, the designer recommends that you not go above 50 hp.

Very nice project!

In my beginning boat building endeavor, I stopped by Nexus Marine and chatted with David Roberts. That conversation inspired me to pursue my boat building addiction! ;o)

Hi Andrew — What a beautiful boat! I’ve seen your excellent workmanship firsthand at past Small Reach Regattas. It looks to me like your Nexus dory is right up there with all of the others. Congratulations! Enjoy your boat!

Paul