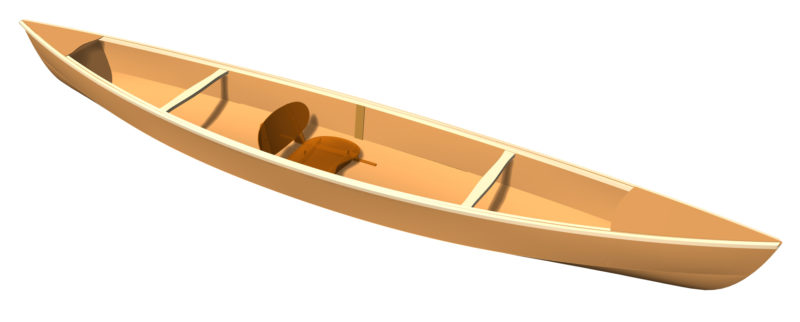

Canoeist Bill Burk, in an article linked to the Moccasin 14 page of the B&B Yacht Designs website, writes that he had built a Moccasin 12 and enjoyed it for day use and fishing but needed something larger to take canoe-camping at lakes in the Pacific Northwest. Regulations at the Bowron Lakes in British Columbia required at least 16″ of freeboard, Ross Lake in Washington State limited length to 14′, and Bill anticipated carrying up to 120 lbs of gear, setting the displacement at 350 lbs. That established the design criteria for Graham Byrnes, and he drew up what would become the Moccasin 14.

Opening photo Graham Byrnes, this photo Christopher Cunningham

Opening photo Graham Byrnes, this photo Christopher CunninghamThe five pieces of CNC-cut plywood for the hull are joined with these sawtooth finger joints.

B&B’s Basic Kit for the Moccasin 14 includes a 24-page manual, illustrated with drawings and photographs, and the plywood parts for the hull and paddle blades, all CNC-cut from 4mm plywood. The hull is made from five precut pieces: a center panel and four identical end panels. Each end panel incorporates half of a side panel, one side of the bow or stern, and the end of one side of the bottom. Finger joints, slathered with epoxy, hold all five pieces together. After the epoxy has cured, the joined pieces lie in a flat plane, ready to fold into shape.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe forward end of the chine transforms from a pronounced angle to a smooth curve.

The center seam at the ends is stitched together with cable ties, bringing the ends from flat to vertical. The sides, now splayed out, get stitched next. The chines have interlocking tabs that assure exact alignment, so there’s no fussing with an edge-to-edge contact and poking at wired ties. Pulling the chine joints tight forces shapely compound curves in the ends of the hull, and the side panels eventually meet amidships to get connected with plywood butt blocks.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe plywood doubler that spans the area between the two thwarts reinforces the seating area.

At this point the hull is hogged, and that’s where a building a cradle comes in. It’s one of the many add-ons to the basic kit and will assure the hull takes its proper shape. The center of the cockpit gets a second layer of plywood, and as that doubler is glued in place, screws driven along the centerline pull the hull down to the cradle’s long wooden I-beam. When removed from the cradle, the hull has a straight keel.

From this point on, the canoe’s completion is standard boatbuilding. Breasthooks, inwales, outwales, and thwarts can be cut to patterns in the basic kit or purchased as an add-on, ready for installation. A keel, epoxied to the bottom, protects the hull from gritty shores and gives the hull better tracking. The plywood paddle blades, supplied with the basic kit, take on a curve when glued to the paddle shaft, also supplied as a pattern or as a factory-shaped piece.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe seat, provided as an add-on kit, is a worthwhile addition for the comfort and paddling efficiency it provides.

The seat is sold as an optional kit, and I’d recommend adding it to your order. Sitting on the hull puts you too low for comfort or power, and cushions make a sloppy connection to the boat. The B&B plywood seat is set at a comfortable angle and high enough to put your hips higher than your heels—much better than sitting with your legs straight out—without compromising stability. The seat’s frame is contoured to pull the seat top into a single broad curve at the back, providing relief for the tailbone, and a double curve at the front to cradle the legs.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe broad pivoting backrest offers comfortable support.

While the kit doesn’t include a foot brace, you could, and should, take a cue from the backrest mounts and set a stretcher from side to side, high enough to meet the balls of your feet. With a foot brace, you can press yourself into the backrest, stay locked in the seat, and paddle with more power.

The canoe is light—it should come in at 38 lbs—so it’s easy to carry. The inwale provides a good grip for a solo carry with the canoe hung over a shoulder. The seat isn’t secured in place, but it will rest against inside the canoe, kept from sliding out by the inwale. Adding a yoke to put the weight on both shoulders with the canoe overhead would be a good shop project if you have in mind to do canoe tripping with long trail portages. For a tandem carry, the breasthooks offer good handholds.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe inboard ends of the paddle blades are shaped with a small lobe that sheds water before it can run along the shaft and get the paddler’s hands and lap wet.

When the canoe is sitting in the water, the seat is set between to two long cleats that center it and allow fore-and-aft adjustments. With a paddler’s weight on the seat, it stays put. I could make adjustments by pushing down against the hull with my knuckles to unweight the seat and scooting it where I wanted it.

The backrest has three positions to get the paddler in the right place for proper trim. The aft setting was appropriate for my 6’ frame. The backrest’s curved plywood panel was comfortable and provides good support down low where it doesn’t interfere with torso rotation during a full, powerful stroke. The seat was comfortable too, and if I’d had a foot brace I could have added a bit of leg drive to the stroke, pivoting my hips slightly in the seat.

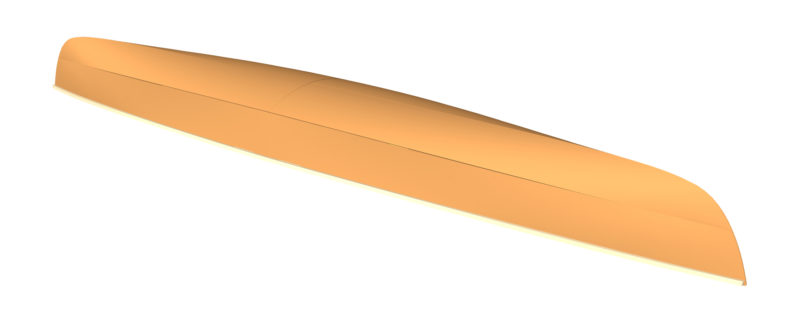

The Moccasin 14 is rated to carry an adult and one or two kids. With my 200+ lbs aboard, the canoe had about 8” of freeboard, and with a beam of 28″ the gunwales weren’t so high that I had to reach over them. I could paddle with a low, relaxed stroke. The initial stability was a little soft, but very good given the 28″ beam. I was quite comfortable taking my hands off the paddle to take notes. The secondary stability kicked in quickly and reassuringly when I edged the canoe.

Underway, the Moccasin tracked well and didn’t yaw excessively between strokes. Turning in place through 360 degrees took 14 strokes—seven forward on one side, seven backing on the other. The keel makes the canoe favor tracking over quick maneuverability, appropriate for a canoe designed for tripping, traveling lakes and slow-moving rivers. The Moccasin took well to being sculled sideways; it was a fun way to maneuver.

Graham Byrnes

Graham ByrnesPutting the power on, the author was able to push the Moccasin at 5-1/3 knots. It maintains good trim even at speed.

Equipped with a GPS, I did some speed trials. I could easily sustain 3-1/2 knots at a relaxed cruising pace. Working up to an aerobic exercise pace brought the Moccasin to an average of 4-1/3 knots. Paddling all-out for a few dozen yards, I did 5-1/3 knots. At top speed, the canoe stayed in good trim and its stern didn’t squat.

I didn’t have much wind during my two trails, just 8 knots. Paddling across the wind, I didn’t detect any weathercocking. I’d take a course across the wind, stop paddling, and watch the bow; it didn’t veer to windward. There were no waves or wakes, so I could do any rough-water testing, but, as an open canoe, the Moccasin 14 would have limits to the amount of chop it could handle. For lake tripping where adverse weather could make the going sloppy, spray decks and flotation, either as built-in airtight compartments or float bags lashed in place, would be in order.

The Moccasin 14 has an unusual construction that makes for a quick build and a shapely hull. And while it was designed for cruising with a big load of camping gear, unburdened it’s quite playful. It could make use of those brief windows of time when there’s a break in your schedule and the weather, and just as ably turn a vacation into a memorable adventure.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is editor of Small Boats Monthly.

Moccasin Particulars

[table]

Length/14′

Beam/28″

Height/11.5″

Weight/38 lbs

[/table]

The Moccasin 14 kits are available from B&B Yacht Designs. Prices range from $415 for the Basic Kit, with just the plywood pieces, to $1,025 for The Works, with everything you need to complete the build, ready for paint or varnish.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Looks like a nice winter project to me.

This is a great size for a solo canoe. It’s long enough to be reasonably fast, and light enough that just about any adult can carry it. Many years ago my wife had a beautiful 13′ freestyle canoe that was light as a feather. It was wonderful for spooning around on small ponds, but left something to be desired when she tried to keep up with the guys in their 15′ to 16′ canoes on cruises. She finally pressured me into designing and building her a 14′ x 29″ canoe. That extra foot mitigated the speed differential enough that she could easily keep up with the group, yet her new canoe was still light enough for her to car-top on her own. For most adults these medium size solo canoes are a much better choice than those too-popular 10′ to 11′ Wee Lassie models.

I looked for two years for a boat just like the Moccasin 14 without success. They were either too big, or too heavy, or too small. I finally gave up and bought a Wenonah voyager (14′ made of Kevlar and rather pricey). Oh well.