It rarely gets cold enough here in Seattle to keep me from getting out on the water, so I’ve been getting year-round exercise and recreation paddling my Struer K-1 trainer on the canal that connects Puget Sound to Lake Union. The launch ramp is only 1-1/2 miles from my home and I’ve made this outing hundreds of times, so often that it has become an efficient routine that takes well under two hours from the time I decide to take a break from work to being back at my desk, rejuvenated and clear-headed.

This dock, at the ramp just 1-1/2 miles from home, is where I’ve launched the Struer kayak many hundreds of times to go paddling on Seattle’s inland waterways.

When there was a break in the wind and rain on the last Sunday of last November, I changed into my paddling wet suit, loaded the kayak on the roof racks, and headed for the ramp. The news being what it was in 2020, I usually didn’t listen to the radio, and instead put the seven-minute drive to good use, often doing memory exercises. On this particular Sunday, I was trying to remember cast members from the movie Young Frankenstein. Gene Wilder was easy and I could picture Peter Boyle, both as the monster and as himself; his name wasn’t long in coming to mind. I knew that the name of the actress who played the ingénue laboratory assistant was one I’d be able to recall, but I got stuck on the similar-sounding name of Vikki Carr and it took me a while to come up with Teri Garr. Later in the drive, out of the blue, the face of a neighbor I hadn’t seen in over a decade came to mind, and his first name dawned on me in a few seconds: Craig. I was pretty sure I wouldn’t be able to come up with his last name, but a half minute later, after I’d given up trying, it too popped into my head.

Within a couple of hundred yards from the ramp and feeling pretty good that my memory wasn’t too far gone for a 67-year-old, I heard a thump on the car roof and caught a glimpse in the driver-door rear-view mirror of a brown diagonal shape crossing the field of view. The kayak had flown off the racks.

I pulled off the street and walked back to the delicate, 30-lb Struer. It had flipped over and come to rest upside down on a diagonal across the edge of the roadway, half on concrete, half on the dirt and gravel of the median. The car coming up from behind had plenty of distance to stop and the driver rolled down his window and asked if I needed help. I replied “No, thank you. I’ve got it.”

I picked up the kayak, got it out of his way, and carried it back to my car to inspect the damage. Aft of the cockpit there was a T-shaped crack in the deck. It was as big as my hand and had a gumball-sized rock wedged between the jagged edges of one of the tears. The rudder blade was bent from vertical to nearly horizontal and there was a 1′-long hole in the bottom, just ahead of the rudder. I looked up and down both sides of the road looking for a missing piece but didn’t see any stray bits of the hull. I didn’t realize until I got home that the skeg, which guards the rudder, had been punched into the hull and stayed there.

I suppose I could have been angry, but I was numb with disbelief, not by why my kayak could have flown off the car, but by how I could have missed something I had never failed to do in nearly a half century of driving boats to the water: tying one down on the roof rack.

In the instant I saw the kayak in the rear-view mirror, I knew what had happened: I had made one small change in my routine. I have been loading the Struer the same way for years: I open the twin doors to the garage, slide the kayak off the carpeted eye-level shelf it shares with my lapstrake canoe and my son’s two paddleboards, and carry it to the car where I set it on the foam cradles and tie it down. On this Sunday, right after I’d put the kayak on its cradles, I glanced at the garage. The doors were open, as they always are at that point in the routine; I don’t close them until after I tie the kayak down. But one time last year I’d forgotten to close and lock the doors, and I was surprised to see them open when I came back from paddling. Not wanting to forget this, I walked away from the car and closed the doors. By the time I had returned to the car, I had slipped into the rest of the routine—the steps I do without thinking— got in and drove off.

If the bow of the kayak were visible from the driver’s seat, I would have noticed it bouncing and swaying; if I were heading to a distant put-in, I would have, as a backup to memory, rolled the window down, reached up and checked the tension on the rope.

The kayak stayed put for five turns, four stops, a 1/4-mile of arterial westbound at 25 mph, and 3/4 mile of boulevard southbound at 20 mph. It might have been a bump in the pavement that lifted the bow enough for the kayak to take its short flight.

The fall of the Struer from my car’s roof racks left the rudder’s stainless-steel shaft bent nearly 90 degrees.

The skeg, which keeps weeds from getting caught on the rudder, got punched into the hull. I couldn’t find any missing pieces on the road and was lucky that the skeg didn’t fall out through the hole on the drive home.

When I first picked the kayak off the road, the longitudinal part of the crack in the aft deck was tightly holding a piece of gravel; I couldn’t tell what had hit the deck here.

While the stern sustained the most damage, the bow took a hit, too, probably on a bounce as the kayak turned upside down.

As bad as the damage was, I had fixed the kayak once before and already knew how to approach the repairs. It had been air-freighted, brand new, from the Struer factory in Denmark, protected only by a soft, translucent cocoon of bubble wrap and a “Top Load Only” label. The label had evidently been ignored and the kayak made the flight to Seattle under a pile of other cargo. The deck and hull had pancaked, splitting the seam between them and breaking deckbeams free of the gunwales. The corner of a box or a crate had pushed through the bubble wrap into the foredeck, tearing through the plies of hot-molded mahogany. I’d put the kayak in slings and left it hanging from the ceiling in my basement for about two years as I mulled over how I’d put it back in working order.

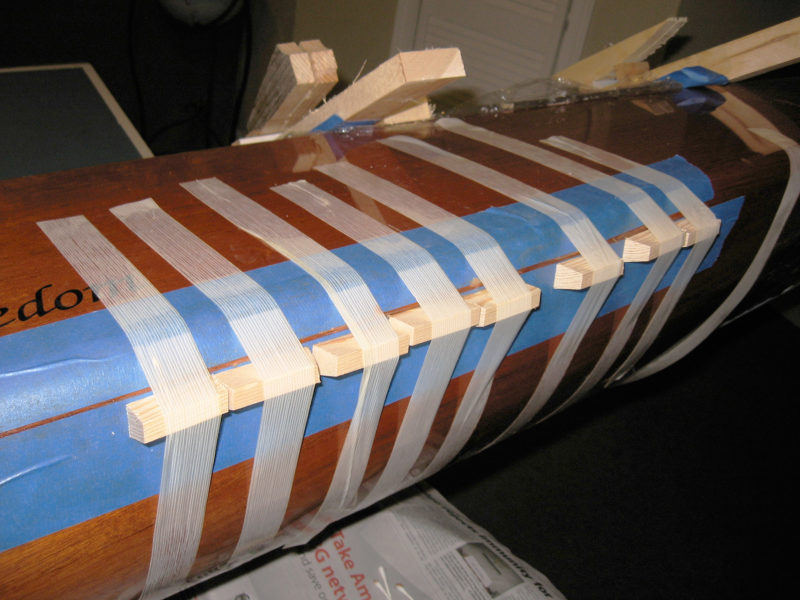

Repairing the damage done to the Struer in transit from Denmark was rather complicated. Bringing the collapsed deckbeams back into position would restore the boat’s shape; planking clamps could work on the deckbeam forward of the cockpit and the rest required bicycle spokes inserted through the hull—their flared hub ends hooked under the beam ends—and drawn up with blocks of wood and slotted wedges.

The seam between the deck and hull had split in several places. Masking tape limited the spread of epoxy and packing tape drew the edges back together. Blocks of wood under the packing tape pushed the edge of the hull back in line with the deck’s edge.

The cracks made by a box during shipping required gluing a piece of 1/8″ mahogany plywood to the interior side of the deck. A piece of 3/4″ plywood inside temporarily backed the mahogany. Clear plastic food wrap and Plexiglas provided a surface to pull the damaged area flat and provided a view as drywall screws squeezed everything together.

The finished repair of the shipping damage was as smooth as it had been new. I didn’t bother tinting the epoxy to match the mahogany and hide the boat’s history.

Afloat for the first time, the repaired Struer proved a great pleasure to paddle and provided great exercise. It became my most frequently used boat, taken out well over 150 times each year. This time, it won’t take two years to make the new round of repairs. I’m eager to have the kayak available again for the outings I’ve come to rely upon for physical and mental wellbeing. I trust the Struer’s new scars will make an equally indelible mark on my memory, a prompt to tie the kayak tightly to the roof racks. ![]()

Ow! Glad it was only the kayak that was injured, and not another motorist following behind you.

When my wife and I were taking our beginning sea-kayaking course in the Seattle Mountaineers Club almost 25 years ago, our volunteer instructor spent a good half-hour demonstrating how to load, tie down, and unload a kayak. Something he said made a lasting impression on me: “More kayaks have been destroyed on the highway than on the water.” I doubted then (and still do) that there was any factual foundation for the claim—how would anyone compile national or worldwide statistics?—but it seemed at least possible. To this day I still hear that warning in my mind’s ears whenever I load our kayaks, and double-check every strap and rope.

I’m forever concerned I’ll make this same mistake. I stick to my loading routine as though it were superstition. So while I haven’t forgotten to tie down a boat yet, I did try to drive into the low-overhead garage when coming home once. The boat was OK, but the roof rack broke. And yes, the dent is still there on the garage trim.

Changing a regular routine has probably put a lot of cars in the water at boat ramps too.

I had to repair my Cosine Wherry after it was rear-ended by a semi.

Ouch! One thing I like about wood and fiberglass is that it can easily be repaired.

Nearly the same happened to me two years ago: Back from a winter trip on a small creek in nearby Alsace called Selzbach—a very nice place in the heart of Europe you should visit—I lifted my plywood canoe (Kymi river) on the car top. Instead of fixing it, I first cleaned my muddy boots. Jumped in the car then and drove off. Bang! My former Old Town would have given a bored smile, but at the Kymi, a half-meter-long crack between two planks appeared. I fixed it later, but I can see the crack all time when sitting in the boat. I’m 58 now. What will happen when I’m 68? 😉

Been there. We are all creatures of habit and subconsciously trust the routine will avoid a problem. They never completely avoid a problem of course, just minimize risk. At work we use many different types of human-performance tools to avoid this, but mistakes still happen, well, as my teenagers would say “well – humans”.

I really enjoyed seeing your innovative approach to your first repairs to the Struer, never heard of that make before. Need to check it out. My go-to solo kayaks for exercise and mental health are the Pouch E65 and my absolute favorite, the Klepper T9.

Chris,

Wait until you get to 80, then one’s short-term memory really becomes aggravating!

I only lost one boat on the highway in 50 years, fortunately is was a Tupperware C-1 so no harm was done. Plus it was hard to tell new road scrapes from older river rubs.

Routine is important. I often have the challenge of fending off admirers questions about my stripper kayaks while I’m trying to tie them down, so part of my routine is to go over every tie-down once again before I get in the car.

It’s amazing that it stayed on the roof as long as it did!

Pat McManus, outdoor humorist and author, wrote a story about drain plugs and their propensity to be absent when launching boats. He suggested they be the size of a manhole cover so that one would know immediately it was missing, as opposed to realizing the problem half a mile from the dock.

Routines can be helpful. Imagine if you had to figure out every step every time you did a similar task?

On the other hand, routines can get you in trouble as you have reminded us.

There is a reason that pilots have checklists they go over, before every single flight.

A related story: A few years ago I loaded both kayaks on the Subaru at home one evening and left them overnight, planning an early departure the next day. In the morning I’d driven about half a mile from home when an upside-down cat face suddenly appeared in the windshield, peering down from the roof between the boats.

Before I could figure out what to do, the cat scrambled off the roof, took a flying leap off the hood, and landed on the road in front of my car. I was rolling at about 30 mph and was sure I was going to hit it. But as I smashed the brakes, the cat hit the road on all fours, kept its balance, and scampered like a demon off the road, unhurt.

Since then, my pre-departure checklist has included looking for stowaways in and between the boats.

Oh, I had one of those moments, too. After paddling, I secured my boat to the roof of my Subaru Forester, put all my gear in the back hatch, and began the drive back into town. I was aware that the noise level in the car was higher than usual and looked around to see what the cause could be.

I’d failed to close the rear hatch, and much of my gear was scattered along the road in my wake. Traffic was very light, so I assume that not too many people saw me retracing my route to gather up all my gear. That would have been very embarrassing.

Your kayak crash reminded me of the time I saw my briefcase flying off the back windshield…or coffee mug…or dictaphone… or bag of groceries. (Note: nothing in the last 10 years though). Or when, like you, I changed my routine after a great row and backed my Buick Enclave with the back hatch still up into the garage…$2500, of which insurance covered $2000! The pictures of your wounded kayak took me back to the days at Vanderbilt Medical School when all of us were sitting in a lecture hall in front of a huge screen with a patient’s damaged liver, or heart or limb on the screen wondered ”What to do?” “How to repair?” Yikes! Glad it all worked out well for you. And, a good message to all of us Boat Haulers: Keep your head in the game, run your checklist, keep with your routines, and check ties before leaving.

I read the article about you kayak taking flight; she’s well built to take that impact with so little damage. Thanks for sharing the story, a good learning lesson for all of us. My nemesis is tying something down but the line or strap works loose anyway. They’re sneaky. So I stop and check tie-downs at 1 mile, 10, and then 100. A friend gave us that tip. He said it worked for him, and if the object was still tied down after 100 miles it would go another 1000.

Great tip!

Good to hear many of us are not alone with these moments. This autumn, I made the mistake of lifting my open plywood lapstrake canoe on top of car without attending the tying up immediately, heading to fetch some gear left on shore. At 45 mph, the canoe went airborne, and I had exactly the same rearview-mirror moment you described. I was lucky to get a way with only minor scratches and a tear in the skeg. I take this as a proof of the extraordinary strength of glued plywood lapstrake construction. Struer is more refined and I guess it was never built to take any extra loads, but to be as light and fast as possible.

Well, Chris, just proves you still have warm blood running through your veins. No lost kayak ( I paddle most every day a Mirage in Australia ). I’m near that 80 mark and managed to leave my man bag (wallet, pocket knife, house keys, etc.) on the car roof as I loaded the groceries. Yep, drove off with predictable results. On arriving home got a call from an unknown person saying they had found it. Come and get it! On collecting it it was obvious that they were not strong financially, but they would not hear of accepting our offered reward! We resorted to hiding our offer in their yard and ringing them with its location in gratitude. World is an okay place,- no? Like you I need routines but that short-term memory needs constant work.

Innovative kayak repair. Enjoy your writing a great deal.

Same thing happened to me with my Wood Duck 10. Got distracted and

forgot to hook the bungee cords. Was lucky this time. It was in the

bed of my truck and moving slowly when it slid out. Just minor scratches.

Quite a few years ago, very early in the morning, we were driving home from our vacation cabin in Downeast Maine. There had been a car/utility-pole accident overnight in Hancock and hidden in the darkness were electric wires hanging down just enough to hook and rip our two CLC Chesapeakes off the car, rack and all, and dump them in the middle of the road. Both were damaged but savable. There followed a long day that involved purchasing a new rack the instant a local bike shop opened that morning and making the 10-hour drive home. But that’s not the end of the story. We had a firm paddling event the next day that we had to attend. With the proper application of gaffer tape I was able to make the boats at least watertight if not attractive. Both boats were repaired by me over the winter and are still paddling.

I’ve been lucky . . . so far. The only time things came loose was about 30 years ago when the leg of a sheet-metal roof rack gave up after hitting a pothole on the Cross Bronx Expressway. We crawled back to Sebago Canoe Club and left the boat behind.

I became an instant convert to Thule’s solidly designed racks. I also switched from cordage to belts with cam locks. Even so, the rig still gets checked regularly.

Your story about the initial damage when coming from the builder struck a cord with me. Some time last century, I built an International Canoe for a friend who lived in Toronto and I had to ship it from Calgary. I had not budgeted for a crate or the time to make one and the idea of an idiot-proof crate was tumbling out of control in my mind, getting heavier and heavier. Finally I gave up on the idea of a crate and tied the boat down to a pallet with all 17 feet of her gleaming varnish exposed. A truck drove up to my shop and the driver and I loaded her in, lifting at the bow and stern and the pallet going along for the ride. As he got ready to leave he said that he was just going to the warehouse where it would go into a bigger truck. A week later the friend called me to say that the boat had arrived without a scratch but the pallet was in rough shape. I wouldn’t recommend this method but I think the varnish spoke to those loading and unloading the truck and they heard it.

Chris,

That is a beautiful repair! You did a fabulous job.

We have a saying in aviation: “There’s those that have, and those that will.” It’s not fatalistic, rather an acceptance that eventually chance catches up to you. It’s easy to say it’s not chance, rather some kind of malicious forgetfulness, but I always give Murphy his due. It’s his way of gently(?) reminding us to return to the present. Glad it came out as well as it did. And I’m really glad it wasn’t “first dent.”

I can sure empathize.

— By their stretchy nature, bungees are not suitable for holding down anything that could become airborne as a result of their failure. My Windsurfer lifted off at 70+ mph and narrowly avoided a head-on collision with a tour bus. I would have been at fault.

— Force of habit can be our enemy. When I’m moving a single kayak I strap it flat. When I’m moving two, I use a Thule Hull-a-Port kayak rack for one. This day, I only had the one, but it was on the Thule rack. The bow punched the garage door off its track. At least the kayak was undamaged.

My goodness.How could you have done such a stupid thing?……Not You…Us… A long time ago we finished a Lightning Class District Championship off Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York. While heading back out on Long Island heading home, the Lightning looked like it had a mind of its own bouncing up and down and sideways. We’d forgotten the tie downs. If anyone has driven around Brooklyn heading to Kennedy Airport on the southern Parkway you know that many of the potholes date back to the turn of the century—like 1890, not 1990. Luck was with us.

Your story reminded me of three incidents. About 25 years ago, I got an inquiry from a guy in New York about building him a Pygmy Coho (Why? I have no idea, as I’m in Bellingham). So I built the boat, and arranged to have it trucked back east on a load of Ocean Kayaks (plastic sit-on-tops) out of Ferndale. I wrapped it well with bubble wrap, and O. C. added strategic cardboard for further protection. It was agreed that the Coho would ride on top of the load of plastic boats. As you have probably guessed, when the client went to pick up the kayak, it was badly caved in at the deck. He had already paid me, and his insurance compensated him. He said a young guy picked it up as insurance salvage, and that’s the last I heard of it. I don’t know whether the client ever ended up with a kayak.

Second story involves a kayaker who was partnering with a pal in a start-up called “Chuckanut Bay Kayaks.” The guy in question decided to build one of their boats for his wife. When he loaded the new boat onto his car, he secured it only with bow and stern lines—no belly lines or straps. He blew off his partner’s warnings about this, and sure enough, the kayak blew off as he was driving home. Totaled the boat.

Third story happened to my Easy Rider kayak. I had ridden with a friend to the put-in in his van. When we returned to the beach, we tied kayaks to the van roof, but I neglected tying down the bow line. As he drove off the beach to the parking lot (where I had intended to deal with the bow line), I heard a loud crunch. You can all guess what this was about. When my bow line got sucked under his front tire, it broke the kayak over the roof rack about in line with the cockpit. It was broken from the bottom almost up the the deck seam. I repaired that break with epoxy and fiberglass, and it actually turned out quite well. But I never painted the repair (the boat was yellow), because I thought it would be an object lesson to anyone who saw it.

I know of at least one other person who has made the same mistake.

And a comment to Patrick: I learned to never trust bungees to secure a kayak. Never, ever.

Feeling bad for you and ,your boat, Chris, but a lot better about all the company. About 2 years ago, I’d finished another kit yak and was determined to load 4 atop the Outback and tow the Pygmy Wineglass Wherry in a utility trailer—so many grandkids to get on the water. It worked,

but when I used the same rig for just two Pygmy Terns, I tried a new tie-down routine.

I kept speed under 55 on SR 520 heading home from Bellevue but faster, large trucks passed me and (I think) the turbulence generated a dramatic weathercocking event. I, too, saw the boats leave the vehicle in the rearview mirror. Both had bowlines yet attached. I moved them against the center lane Jersey barrier, damn lucky not to engage any other vehicles. The highway assist truck soon arrived and the driver helped me secure the parts. And clear a way at 15mph to exit in Redmond—about 10 minutes.

With a big paddle about two weeks away, I pondered for a day, then rebuilt a bow (about 10″) on one and the other’s stern. I scavenged some left-over okoume and called up 20+ years of builds and repairs on 6 kits. Keeping the extremes aligned with the long axis was challenging but the 10′ view is not so bad.

I have a 1966 Rob Roy Struer hanging in my house. A friend wanted to see if it would hold him. Trying to get in from the water he cracked the hull. Another friend fell on it causing damage. Delicate. Who needs friends.

I leave the loose end of the straps hanging and close the doors on them. It stops the ends flapping in the breeze and I can easily see that the straps were used as the ends are dangling inside the car.