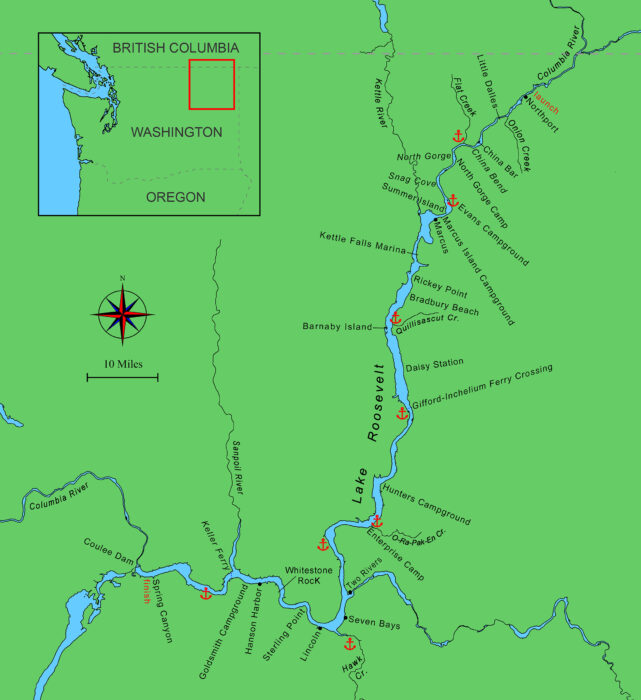

Ever since I first saw Lake Roosevelt, a Columbia River reservoir in northeast Washington, I’ve wanted to voyage down its 133-mile length. The place seems made for small-boat cruising. The shoreline is almost entirely undeveloped because the west side of the lake is mostly tribal lands and the east side mostly federal lands. The sandy beaches, coves, and campsites are seemingly endless. The summer of 2023, decades after my first encounter with the lake, the stars aligned, and I was able to shove aside the affairs of life on land for two weeks. While August is not the best month for a voyage on Lake Roosevelt, because of the heat and light winds on the lower lake, this was my time. I packed the boat and on August 7 my wife dropped me off at Northport, a town on the left bank of the Columbia River about 10 miles downstream from the Canadian border.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorFully laden SIRIUS weighs only about 600 lbs and can be comfortably towed behind a family car.

Here, the Columbia isn’t a part of Lake Roosevelt but a large, forceful river, not yet blocked by the Grand Coulee dam. This free-flowing stretch is the domain of motorboats and canoes, not sailboats. I launched at the Northport ramp, just upriver from a 1⁄4-mile-long cantilever truss bridge. A strong, blustery upriver wind and swirling downriver current full of eddies and whirlpools made motoring under the bridge interesting. My 22′ mainmast just cleared the bridge. Beyond it I killed the motor and hove-to, then went forward to set the mainsail. Ordinarily SIRIUS, my modified Michalak Jewelbox Junior with a cat-yawl rig, heaves-to perfectly, but with the solid Force 5 wind countering the roiling current, the little boat didn’t know what to do and wandered all over the river. I balanced on the foredeck, trying to loop the snotter around the mast and hang the sprit boom. Holding the end of the boom on my shoulder, I struggled while the mainsail, its clew clipped to the other end of the boom, did its best to knock me overboard.

The boat eventually grounded itself on a gravel bank near the river-right shore, and I was able to get a reef tucked in and set the mainsail properly. With a pivoting leeboard, kick-up rudder, and 1″-thick flat bottom, I never worry about running aground, which is one of the reasons I like SIRIUS. Indeed, I usually sail her right onto the beach.

Just a few miles downriver, the railroad line crosses a stream at the mouth of Onion Creek and the northern border of the Lake Roosevelt National Recreation area.

After pushing off the bank with an oar, I hauled the leeboard down by its pendant, caught the wind, and sailed out into midstream. I tried tacking but got caught in irons, stalled, and rolled about at the mercy of the conflicting wind and current. What the heck? For a flat-bottomed plywood box, this boat usually points high and foots fast, a paragon of sailing virtue. But I was beginning to understand the advice given to me by a friend, “Don’t launch a sailboat north of China Bend.” I realized the strong current from astern made steerageway difficult to maintain. I eased the mizzen sheet to fall off the wind a point or two and hauled the mainsail in tight. The boat heeled over and zoomed across the river, making short, broad tacks. As long as I kept the speed up, I could control the boat.

A couple miles below the town, I spotted my wife sitting on the railroad tracks that follow the left bank. She wanted to be sure I had everything well in hand before driving away. I hove-to close to the bank and we shouted our goodbyes. We didn’t expect to be able to communicate for days, if at all, because we knew the area’s cellphone coverage was poor in these parts. As it turned out, I found enough signal to get a call out every day.

As the river flows into and through Little Dalles, the current becomes fast and often unpredictable. With no GPS or detailed chart, I had no idea this narrow gorge existed. For me, discovering the river as I go is a large part of the fun.

With the strong current going my way I covered plenty of ground, industriously short-tacking down the river. In an hour the river slowed, and the wind stilled. Nestled on the left bank was a quiet cove backed by the railroad line that crossed a stream on a rusted trestle bridge. I sailed in and landed to stretch my legs and have lunch. This is the mouth of Onion Creek, the official start of the 133-mile-long Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area according to my only navigational aid, the National Park Service map, which I’d picked up at the launch ramp.

When I left the cove, the wind on the river had died and I didn’t feel like just drifting, so I racked the sprit boom on the cabintop, rolled the mainsail up from the clew, loosely furled it to the mast with the snotter, and started the motor.

As it flows through the Lake Roosevelt National Recreation area, the Columbia River is fed by many streams and creeks. Flat Creek is typical and offered a sheltered overnight spot out of the main current.

Soon the lazy river started to pick up speed. Ahead, it narrowed between tall cliffs and with the aid of my binoculars I confirmed that an eddy line stretched clear across the river! That usually means rapids ahead, although the map didn’t indicate any here. I hurriedly raised the leeboard, donned my life jacket, and made sure everything was squared away. I gunned the motor to maintain steerageway as the current continued to gather speed. I’m no stranger to rapids, but I’ve certainly never run them in a sailboat. “OK,” I figured, “keep the boat pointed downstream, try not to hit anything, and whatever you do, don’t get broadside on a rock.” I’ve lost a boat that way before.

There were no rocks, but the current was powerful and unpredictable, full of 10′ whirlpools and strong eddy lines. The volume of water moving through this narrow gorge, called the Little Dalles, is tremendous. The Columbia has flowed more than 500 miles from its source by the time it reaches here, gathering the flows of countless streams and tributaries along the way.

The forward half of the cabin has a plywood inset to create a stable and comfortable sleeping platform with plenty of storage below the benches on either side. The large windows provide plenty of natural light and excellent all-around visibility from within the cabin.

SIRIUS was grabbed by an unseen eddy and instantly heeled over so far that I let go the tiller and threw myself to the cabin floor to help keep her upright. This was no place for a boat with a deep, hard chine like SIRIUS. The gorge funneled an upriver wind so strong it unfurled the mainsail from the mast; having 96 sq ft of sail flapping furiously about didn’t help matters. Fortunately, the Little Dalles gorge is only 300 yards long, and I was soon out into calmer waters.

Beyond the gorge the wind died again, and the current slowed to about 2 mph, so I lowered the sail and kept motoring. Two or three miles downstream the water went glassy, and I cut the motor, letting the boat drift. The afternoon had turned hot, so I stripped down, jumped in, and swam around the drifting boat. SIRIUS has a boarding step on the stern at waterline, and with the help of the mizzen boomkin and mast, climbing from the water is easy enough.

The footwell in the stern of the cabin doubles up as a flat surface on which to prepare meals, and the flare of the cabin sides provide comfortably sloping seat backs.

Back aboard I broke out the stove and brewed afternoon tea. Two jet skis passed by, heading north. I cooked and ate dinner. The two jet skis passed by again, heading south. That was all the boat traffic for that day. Eventually I refilled the motor’s fuel tank and continued, passing China Bar, a 65-yard-long, narrow island where Chinese immigrants panned for gold back in the 1860s. The evergreen-crested bar looked like a great place to camp, but I had no idea how long this trip might take and figured I’d better press onward. I passed the China Bend boat ramp on the left bank, which is as far upriver on the lake as big boats dare to launch.

The Columbia curved to the west, and I found a cove in the north bank where Flat Creek tumbles down to the lake. I went up as far as I could, tossed the anchor over the bow among the rocks of the creek, and let the boat snuggle against the muddy bank. Despite a late start thanks to the current, I’d made some 14 miles, according to the river-mile marks on the map.

For much of the trip there was little wind and at times the Columbia was a flat calm. With everything lashed in place—the throttle on the outboard’s tiller arm held by para cord and the tiller centered by a length of bungee—SIRIUS needs very little hands-on supervision.

The Jewelbox Junior is a Birdwatcher design, sailed from inside an 8′-long slot-top cabin. For a 15′ boat accommodations are pretty good. Low seats line the cabin sides where the headroom is about 36″. At night, filler boards bridge the seats to make a double berth. A vinyl cover supported on wooden slats snaps over the slot at night or during inclement weather. As tall grasses along the creek brushed the port cabin windows and a hundred little bugs swarmed around my light, I listened to a pocket radio tuned to a Canadian station for company as I read myself to sleep.

The next morning, the silvery beads of a heavy dew covered the boat. I had a pleasant breakfast-in-bed of tea and oatmeal, listening to the chuckle of the little stream and reading The Venturesome Voyages of Captain Voss. Underway by 9 a.m., I motored downriver through the North Gorge where I feared a repeat of my experience in the Little Dalles. I needn’t have worried. Steep, wooded hills reared above the river, but the channel was wide and the water glassy. I stayed close to the right bank where I discovered several little rock-bound coves, one with a waterfall.

In fair weather I roll back SIRIUS’s cabin top to transform her into a high-sided open boat. With the sleeping platform put away there is no obstacle from one end of the cabin to the other. Gear and food are stowed in lockers beneath the side benches while the bedding goes up under the foredeck. In light airs or when motoring I steer from the stern deck but in stronger winds it’s safer to steer from inside the boat.

There was no longer a discernible current; the Columbia had turned into a lake and with no wind, the voyage was turning into a motor-cruise. My little two-stroke outboard was so loud I wore earplugs. I landed to explore North Gorge Camp and walked the train tracks along the shore. The line ran right beside the road at the camp entrance, but the two soon diverged: the road headed inland while the rails veered through the forest close to shore. The rails, spiked to wooden sleepers, were bright with use. Through the trees I caught glimpses of the quiet cove on the upriver side of the camp.

I motored on and by 11:30 a.m. a gentle upriver wind had sprung up. I killed the motor and raised sail to conserve fuel. I had brought only 1 gallon of gas and couldn’t get more until the marina at Keller, about 40 miles below Northport. I tacked downriver and upwind for several hours, making a gentle 3 mph. Gradually the wind grew and at 2 p.m. I landed at a boat launch at Snag Cove. Despite the name, here there is neither cove nor snags. I went ashore for lunch carrying my stove to brew tea but had a beer instead, courtesy of a passing fisherman. The wind grew strong but fluky, and I left Snag Cove reefed, but soon shook out the reef to make better time. I luffed through strong gusts, on and off sailing, becalmed, then wham!…another gust. It was tiring and took several hours to reach the first big bay of the trip, about 1 mile wide and 2 miles long. Here the wind blew strong and steady. Rather than reef, I flew along close to the wind and sailed full-tilt up to the dock at Evans Campground, cast off the sheets at the last possible moment, and leapt ashore with docklines in hand. It was a perfect landing, but no one was there to witness it.

In the height of summer the upper reaches of Lake Roosevelt were almost deserted. There were many quiet isolated spots to pull up to overnight, such as here on Summer Island.

It was 5 p.m. and I was bushed. I set up my kitchen under a pavilion and cooked a good dinner of a homemade polenta-couscous mix with diced tomato, cheese, and tea. I considered sleeping on shore, but it looked like rain and I hadn’t brought a tent. The wind was dying, and I was tired, but I didn’t want to stay on the dock in this exposed location, fearing I wouldn’t sleep well. SIRIUS has pronounced rocker fore-and-aft, which makes her rather tender, so it’s best to beach her for the night. Besides, visitors leaving a boat at the dock all night are supposed to pay for a campsite. I sailed from the dock bound for the opposite shore, only a mile away, but the winds had calmed, and it took me an hour of tacking upwind to cross the bay to Summer Island, one of the many boat-in campsites on Lake Roosevelt that are free of charge and are first-come, first-served. I landed on the sandy shore at 7 p.m. I’d managed 13 miles that day. The beach was sheltered and quiet, and I had the whole island to myself. I bathed in the lake and turned in for the night.

It rained a little that night, but not much. The next day was overcast and cool, and I left the vinyl cover in place over the cabin’s slot-top; it looked like that kind of day. I had a lazy morning, cast off at 10:30 a.m., and sailed away from Summer Island in light, variable winds, chasing ripples across the lake. I didn’t get far and was soon motoring slowly along with sails up. The bay narrowed back into a river between rocky banks and low wooded bluffs, and I could see weeds bending in a gentle current. The water was glassy, reflecting a gray sky.

The sand bluffs just above Marcus Island camp are unstable, particularly between Gifford and Enterprise. All was quiet when I passed by this trip, but in an earlier summer, I saw two cliffs collapse in clouds of dust and sand, reminding me of icebergs calving from a glacier.

Somewhere along the way I passed over the remains of the town of Marcus, one of the 10 communities drowned when the lake was formed. I motored past Marcus Island Campground and out into the biggest bay on the Roosevelt, more than 1 mile wide and 5 miles long. The water here was rippled and the wind light. I was on my last tank of gas, so I killed the motor and ghosted. A gentle breath of air from the north pushed me down the bay from behind, the first following breeze I’d experienced on the trip. I ghosted straight down the middle of the bay, headed for the narrow exit straddled by the Kettle Falls Bridge. Halfway down the bay, the wind picked up and shifted to the west, putting me on a reach, and as I neared the bridge the water grew choppy; the wind shifted to dead on my bow and increased to about as much as I care to handle without a reef. As I got closer to the bridge, I could see that it was not one, but two bridges close together. I’d have to pass under the lower railway bridge first. I short-tacked up close but at the last moment chickened out and sprang to the motor. It came alive at the first yank, I cranked it wide open and motored through, bouncing in the chop. The wind was just too strong and fickle in the narrow gap, and there was little room for error.

After clearing both bridges, I killed the motor and was once again tacking down a narrow river against a strong south wind, heeled well over. Soon the wind quieted, the boat settled back upright, and the flat bottom pounded in a leftover chop. I started shifting my weight to the leeward side of the boat with every tack to heel it over—a flat-bottomed boat has to sail heeled in a chop or it will pound to a stop. I was making little progress and eventually gave up, furled the sails to the masts, and started the motor. I had just enough fuel to get to Kettle Falls Marina, not quite 2 miles below the bridge.

SIRIUS’s roll-top cabin roof is an old above-ground pool liner cut to size and shape. It is supported by thin wooden battens sprung across the opening, their ends held in slots in the coaming. I got the idea from plans of AMOS BROWN in John Atkins’s book “Practical Small Boat Designs.”

I tied up at the gas dock, refilled my 1-gallon gas can, and bought oil and an ice cream.

I motored out of the little marina and raised sail. The wind was now blowing from the north, strong enough that I took in a reef. I ran off to the south, making good time as the wind continued to build and entered the mile-wide bay above Rickey Point, where about a dozen large sailboats are kept on moorings. A mass of low rain clouds rolled down the hills from the northwest behind me, and I considered ducking into a cove on the right bank for shelter. But I was making such good time, the storm wasn’t gaining on me, and I didn’t care to spend the rest of the day swinging at anchor in the rain; so I made sure the cover over the slot-top was snug, put a transparent drop board in the forward companionway, dropped the aft flap, and kept right on going downwind. It felt odd sailing with the cabin battened down for heavy rain. I could see out the windows, but not directly behind, and I couldn’t see the mainsail at all.

Being flat-bottomed SIRIUS can be beached anywhere with a soft landing, and her bow is low enough so I can simply step ashore without getting my feet wet.

Suddenly SIRIUS was hit by a terrific gust of wind and heeled well over, and I cast off the mainsheet as fast as I could. The storm had overtaken me. Because I couldn’t see the mainsail it took me a moment to figure out what was happening. The wind was now blowing hard from the west and the boat was caught broadside on. Torrential rain hammered, thunder boomed, and the wind increased yet again, heeling the boat alarmingly. The only thing I could think to do was to heave-to. I had to plant both feet against the aft bulkhead to haul the mizzen flat, but the boat rounded up. I was amazed that nothing broke, but feared the flogging mainsail would knock the boat down any second. The rudder was hard over to port and SIRIUS was being driven backward across the lake at a surprising rate. I tried to force the rudder over to starboard but gave up as the force required was so great that I feared breaking something; then belatedly I realized that with the mainsail to port and the boat going backward, the rudder should also be to port. The boat knew what it was doing better than I did! I wanted to haul down the mainsail and considered reaching across the foredeck with a knife to cut the halyard, but the only way to get the sail down is to stand on the foredeck and free the boom’s snotter, which is looped tight around the mast trapping the sail lacing and halyard. The storm was frighteningly violent, but slowly I relaxed, realizing there was no immediate danger. SIRIUS is fully self-righting; the buoyancy of the high cabin sides and weight of the inch-thick bottom and 135 lbs of lead ballast will bring her right back up from a knockdown. A good deal of rain was driving in over the front drop board and under the slot cover. I put on my raincoat, life jacket, and hat, and spread a small tarp out to catch the rain coming into the cabin. I’d been blown clear across the lake and was headed right for the sailboats moored off Rickey Point!

I considered dropping the anchor, but with only 100′ of rode I had no hope of it finding the river’s deep bottom before I ran in among the moored boats. The storm moved eastward and the wind moderated, if not the rain. I loosened the mizzen to fall off the wind, gathered my courage and the mainsheet, and sailed downriver, away from the point, and left the storm behind.

When stopping overnight at a beach with a steeper slope, such as here at Quillisascut Creek, I bring SIRIUS in stern-to so that my head is higher than my feet when I’m sleeping.

The wind stayed In the north for the rest of the day, strong enough for a reef, but conditions moderated for a time and the sky shone brilliant blue between broken clouds. At 5 p.m. I landed at Bradbury Beach. The floating dock there was pitching in the waves and the approach was guarded by log booms. I hove-to and tried to furl the mainsail, but the wind was too strong; I had to lower it instead. I started the outboard and steered for the dock but had to abort the attempt. I gunned the motor to spin the boat about, got out past the booms, and ran the bow up on a sandy beach in their lee.

I stretched my legs on solid ground but couldn’t stay. The sky had darkened again; another storm was blowing down from the north. I pushed off the beach and motored south along the left bank looking for a cove. About 4 or 5 miles down, Barnaby Island came into view off the right bank and, just as heavy rain hit, I spied a small opening in the opposite bank and motored into Quillisascut Creek. With the strong tailwind and motoring I’d covered about 20 miles from Summer Island where the day had started.

SIRIUS will sail herself to windward with the tiller held by the bungee and the mizzen sheeted a little freer than the mainsail. My weight moving around the boat has little effect on the heading and I make course adjustments by sheeting the mizzen in or out. The mainsheet comes from the end of the sprit through an eyebolt on the sterndeck and into the cleat—it has no mechanical advantage.

I waited out the storm, then motored back out into the lake to find a cellphone signal and, drifting broadside to the waves and rolling all the while, made a brief call to my wife. The fetch was miles long and considerable chop had built up. Motoring back to the creek, I had to quarter the waves—SIRIUS could not take them on the beam. Well up the creek I put the stern on a bank, tied up to a tree, and tossed the anchor off the bow into the grass on the other side. Only tiny wavelets made it all the way up to where I was. I cooked dinner and ate as the sun set, glad to be in a snug, dry, cabin.

I spent the next morning in the cove. I tidied the boat, wandered the beach, explored the nearby woods, and had a shower under a cataract that tumbled 20′ over moss-covered rocks. At about 11:30 a.m., I took my leave and sailed across the lake on a broad reach before a brisk north wind under blue skies scattered with fluffy cotton-ball clouds. I bore away to run the gap between the west bank and Barnaby Island, a 1-acre wooded islet rimmed in sand and silver-gray driftwood. The passage was too shallow even for SIRIUS. Barnaby Island is no longer listed as one of the boat-in camps, but I could see picnic tables and latrines among the trees. About 1 p.m. the following wind picked up so much that I hove-to and took in two reefs. The boat quieted right down with the double reef. I think I was being overly cautious, worried about another surprise storm. A half hour later I made Daisy Station on the left bank where the gas station, store, and restaurant are now out of business. As the wind died, I shook out the reefs and drifted, bobbing about in the leftover waves.

The 2′-long bow well is self-draining. For the samson post and mast step I was inspired by the setup drawn by Phil Bolger for his Black Skimmer design. I carved SIRIUS’s mainmast from a 35-year-old Douglas-fir. Sitting at the bow while your boat sails on is truly mesmerizing, but it is a little dangerous—if I fell overboard the boat would happily sail away without me!

In a little while a south wind sprang up and I tacked down the lake. The lake here is about a mile wide between low wooded bluffs with scattered sandy beaches. For the first time the wind blew nice and steady. I strapped the tiller amidships with a bungee cord, cleated the mainsheet, and adjusted the mizzen to hold a course about 45 degrees off the wind. SIRIUS would hold her course like this for hours. When we neared a bank, I’d push the tiller over to come about, then center the tiller again and go back to writing in my journal, talking to my wife on the phone, and making lunch. I even washed some clothes, using the aft deck as a washboard and towing them behind on a cord to rinse. I hung them to dry on the boom. While SIRIUS sailed herself, I stood on the aft deck with a hand on the mizzenmast, studying the scenery, or sat on the forward cabintop, mesmerized by the bow wash.

At about 6 p.m., the wind left for the evening. I furled the sails, started the motor, and putted past the Gifford-Inchelium ferry. A little beyond the landing on the right bank I passed a series of coves.

South of the Inchelium ferry dock, I found a small deep cove where I moored up and went ashore to explore the forest before rowing on to an even more sheltered spot for the night.

I killed the motor and broke out the oars for some exercise. I set SIRIUS up for stand-up rowing with 9′ homemade oars. She is no joy to row, but with the sails furled and the leeboard and rudder up I can maintain about 2 1⁄2 mph and have rowed a mile or two upon occasion. (Mostly I use the oars for maneuvering or poling in shallow water.)

On this fourth day, I’d made 15 river miles downstream, much of it beating to windward. I chose a sandy beach in a small cove that my map said was about 75 miles up-lake from Grand Coulee dam. It was wide open to the east, so I would be awakened by the morning sun.

Many of the coves, like this one, showed no signs of human activity—no old fire rings, no trash, and no trails leading into the woods.

The next morning, I was underway by 8:30 a.m., sailing gently downwind past wooded hills interspersed with sheer sand cliffs, sometimes as much as 100′ high. At the base of the cliffs spread beaches of fine, white sand. It was Friday, and there were plenty of smaller powerboats on the water and camps on shore. There was not a cloud in the sky and the day was already on its way to being a scorcher, but it was pleasant in the shade of the mainsail. By 11 a.m. the wind died, and I couldn’t drift on the lake, baking in the heat, so I started the motor. Within half an hour I had landed on an empty sandy beach on the right bank a few miles upriver from Hunters Campground. A swim in the lake cooled me right down and I shaved while standing waist deep in the water, my pocket mirror propped up on the stern deck. After lunch, enough of a breeze sprang up from the south to make beating to windward profitable and I was on my way again.

I made the floating dock at Hunters Campground under sail and stayed long enough to refill my water jugs before casting off.

The Hangkia 3.5-hp outboard worked well throughout the trip, starting every time it was needed. I had a limited supply of gas so used the outboard as little as possible, but even so I burned through 4 of my 5 gallons of fuel.

I tacked to windward the rest of the day, usually with the helm untouched. Many of the beaches were occupied by campers, with boats lined up along the shore, tents pitched, music blaring, and ski boats and jet skis blasting in and out. The weekend had come to the popular part of the lake. About 7:30 p.m. I landed on an empty, sandy beach at the mouth of Oh-Ra-Pak-En Creek for a swim to cool off and remove the sweat of the day. I looked up and realized I was providing entertainment for a bunch of people camped on the opposite shore of the creek who had nothing better to do but sit in the shade and watch the antics of the old guy in the odd little boat across the way. It creeped me out, so I pushed off and motored as far up the narrow and deep creek as I could both for privacy and to get out of the setting but still blinding sun. I anchored among the submerged snags at the head of the creek. Evening sent a breeze down the canyon, cooling me off as I dined on canned chili, diced tomato, some baby Gouda cheese, the last of the bread, and a pot of tea. I had covered about 17 river miles—not counting the endless tacks—almost entirely under sail, which was a record for SIRIUS. The breeze blew all night, making the boat swing to her anchor, and I slept soundly.

Saturday, the sixth day of the voyage, dawned bright and cloudless but the sun couldn’t penetrate up the canyon and I didn’t get underway until almost 10 a.m. I motored down the creek and out past Camp Enterprise, which had at least a dozen boats pulled up along the beach. The shore looked like a tent city. Here the lake jogs westward in a big dogleg. The day was already getting hot as I motored across to the right bank to find a shady beach to wait for a wind. As I neared the far side, the outboard’s fuel tank started rattling sharply inside the housing. I landed in a shady cove and went for a swim as the engine cooled. I disassembled the motor and found the tank mounting bolts had worked loose, an easy fix.

With little wind and not much left in the gas tank, I took to the oars to keep SIRIUS moving. I row standing up looking forward, the oars pressed against the sides of the oak-trimmed oarports like thole pins.

I stayed in the cove for two hours, beachcombing and waiting for wind. The morning was hot and still, without a cloud in the blue sky. Motorboats occasionally chewed up the lake, throwing huge wakes. Finally gentle cat’s-paws appeared on the water. I motored out to meet them, shut down the engine, and ghosted along. I rowed now and then, but it was too hot, and my heart wasn’t in it. It took three hours to make the next 5 miles, to the end of the dogleg where the lake turns south again. Around the bend is a bay more than 2 miles wide. Here, a good south wind sprang up and I tacked a few miles south before it died. It was still early, but I’d had it for the day. There were several coves with sandy beaches on the left bank, but I needed to get out of the afternoon sun and find shade on the right bank. I sailed for another half mile, gave up, and motored on my last tank of fuel across to a small, rock-bound cove that was in the shade on the right bank. I’d managed only about 7 1⁄2 miles.

I dropped the anchor and bathed standing in the self-draining bow well, pouring water over my head with the anchor rode bag. I had my last tomato and the last of the cheese with dinner. Feeling much better, I hung a kerosene lantern from the end of the sprit boom racked on the cabintop—the first time I’d bothered with an anchor light—and settled back against my pillows to catch up on my journal.

Throughout the trip and most especially towards the end, the weather was so hot that I sought shade wherever and whenever I could. Here, SIRIUS is moored in the shade of a basalt cliff.

On Sunday morning, I was vigorously bounced awake by sharp little waves entering the cove. I sat up and was blinded by the low-angle morning sunlight. Groggily I hunted up my watch, it was just after 6 a.m. A reefing wind blew southward past the mouth of the tiny cove. I got an early start and, before too long was heading south under one reef, making great time. About 5 miles along, I spotted a 70′ pontoon houseboat beached on the west shore, looking like a stranded whale. I knew that boat well, having done plenty of work on it this summer. I released the mainsheet, threw the tiller over, and ran the boat up at speed on the sandy beach about 100’ from the houseboat. As SIRIUS scrunched to a stop on the white sand beach I hopped over the bow and startled a black bear that had been foraging near the houseboat. It ran off and scrambled up a sandy hillside sparsely forested with ponderosa pines and sagebrush. That set the dogs on the houseboat barking, and soon my bleary-eyed friends were peeking out at me. It was only 8:30 a.m. We spent an hour chatting, and they generously refilled my gas can and gave me a gallon of two-cycle oil.

I continued south, enjoying the strong following wind and making great progress. I had planned to stop for two-cycle oil at the marina at Two Rivers, the confluence of the Spokane River and Lake Roosevelt, but since I no longer needed any, I continued past.

As the upriver forests gave way to the starkness of sand and basalt, the landscape and heat were quite forbidding. For a while, the shade in Hawk Creek offered welcome respite.

Three miles farther down on the left bank is Seven Bays Marina, home of the only restaurant on the lake. As I neared it, the Roosevelt grew crowded with all kinds of motorboats heading this way and that. SIRIUS carried the only sail in sight, and I was grateful for the strong wind that enabled me to plow through the confusion of wakes and chop. I hove-to outside the marina entrance to furl sails and motored into the courtesy dock where SIRIUS looked out of place among the fiberglass and aluminum powerboats. I enjoyed a cheeseburger at the restaurant and filled an extra gallon jug with gas. I might need it if the weather turned back to hot and still.

After leaving the marina, I sailed a few miles down the lake as the wind gradually faded away and the lake grew calm. Without the wind it became very hot. I started the motor and sat on the stern deck with the tiller between my legs, an umbrella balanced on my shoulder to shield me from the broiling sun. The cabin was a greenhouse, too hot to occupy. I entered the wide mouth of Hawk Creek where, on its north shore, a wedge of shade was cast by a sheer basalt cliff that plunged into the lake at the mouth of a small cove. SIRIUS had turned into a furnace, the wooden cleats and dark green trim too hot to touch. I beached in the shade. The water was murky with fine clay silt, but I was far too hot to care and spent an hour floating in the shade on a seat cushion, then sat in the shade reading and writing until 6 p.m.

The 40′-high waterfall at the head of Hawk Creek narrows to a fast running stream in late summer, but in the spring is a spectacular torrent.

In the cooler evening I motored up the creek. The entrance is 300 to 400 yards wide with many sandy beaches and campsites, gradually tapering down to a narrow, winding channel enclosed by tall, sheer cliffs called the Palisades. The sun couldn’t penetrate in there and it was cool in the shady passage. Little kayaks and paddleboards splashed about like water bugs, and several motorboats were anchored, one with smoke curling up from a barbecue on deck. I motored on through and the Palisades opened up to reveal shady Hawk Creek Campground nestled below sage-covered basalt hillsides. I motored, rowed, then poled as close as I could to the 40’ waterfall at the head of the canyon, but SIRIUS ran aground about 200’ shy of it. The day was fading, and eventually I headed back downstream and anchored in a shady, rock-bound cove on the south shore near where the mouth of the creek opens onto the lake.

During dinner, while spreading peanut butter on a cracker, I carelessly dropped my sheath knife onto my air mattress. Naturally, it landed point-first. I had no patch kit, and I spent the rest of the trip sleeping on a flat mattress.

As I neared the end of the trip and cruised through increasingly rugged terrain the wind dropped off to almost nothing and the daytime temperature soared to over 100 degrees. I made frequent stops at shady beaches in my efforts to cool down.

On the morning of my eighth day out, the radio warned of a heatwave with temperatures in the shade exceeding 100 degrees. From here, Lake Roosevelt no longer heads south but turns northwest. Underway at 8:30 a.m., with no wind and not a cloud in the sky, I motored slowly close to the left bank where there was the most shade. I sat on the stern deck, with the umbrella on my shoulder, and occasionally plunged my shirt over the side and put it back on, dripping wet. The lake here is 1⁄2 mile wide and bordered by desiccated grass-covered slopes rising to rocky sage-covered hills. Gone were the forests of upriver; this was desert country. Gone also was the boat traffic. It occurred to me that a desert is not the ideal location to sit out a heatwave, and that I was now utterly dependent upon the cheapest and perhaps most unreliable outboard sold, which had never run so many miles without failing. If it quit, I might be in a bit of a pickle. I reasoned I’d row to the nearest available shade, cool off in the lake as necessary, and either fix it or wait for a wind to carry me to the nearest boat ramp where I would call my wife to come get me. I still had plenty of food, even if it was of the oatmeal, ramen, and canned tuna variety. With this contingency plan in place, I motored on.

I passed the ramp at Lincoln and the camp at Sterling Point, making perhaps 7 miles before I landed in a tiny cove with cool, crystalline water caressing a beach of coarse sand with tiny wavelets. Shade was provided by a sheer 40′ granite cliff and there were cool, rounded boulders to lean against. Seldom have I chanced upon such a nice spot. I stayed two hours, and maybe should have stayed two days, until the heat lessened.

Whitestone rock rises 700′ above the lake. The boldness of the cliffs offered little in the way of shade and with the temperature topping 100 degrees in the shade, the heat out on the glassy lake was exhausting.

I motored the next stretch at what passes for high speed with my outboard. From time to time, I dipped a cloth in the lake and wrung it out over the fins on the cylinder head to cool it down. The lake was glassy as I passed Whitestone Rock, a sheer-sided granite monolith that rises 700′ from the lake. The lake is over 1⁄2 mile wide here, the left bank rocky, the right bank rising in barren brown steps clothed in short prairie grass.

The engine ran out of gas after about 5 miles. I poured gas in and continued to the next shady beach to cool down. After a break in the shade yet again, it seemed better to cruise at 3 or 4 mph, so I motored slowly on past the ramp, the three-dozen lakeside houses at Hanson Harbor and the picnic tables at Goldsmith Campground and made the marina just past the Keller Ferry landing where I refilled my gas can yet again. I sailed for perhaps a mile beyond the marina in a light, fluky headwind to a big rocky island, but I soon gave it up as unproductive. I motored to the left bank and ran the bow up on a muddy beach in the shade below a steep bluff topped with houses. I drank two quarts of Gatorade while lying on my back in the boat with my feet propped up on the aft deck and passed the time reading.

As the daylight faded an unexpected notch opened up in the cliffs giving onto a short rocky cove where I could spend the night.

At 7 p.m. I refilled the outboard and slowly motored into a blinding setting sun, past a confusion of jagged pillars, towering cliffs, and talus-draped ridges lining the bank, and turned into a deep, narrow opening that unexpectedly appeared among the cliffs and pillars. This led into a deep cove ringed with craggy granite, with a narrow dry wash choked with brush at the back. As I came in, a river otter slowly swam out. I’d pushed about 25 miles and was bushed. I set the anchor over the bow, tied the stern to the shore, bathed while standing in the bow well, and went to bed.

On the morning of my ninth day on Lake Roosevelt, I got underway at 8:30 and motored slowly along the left bank as before, stopping about every hour in any scrap of shade I could find to cool off. With only 10 miles to go, I was not in a hurry. I had arranged for my wife to pick me up at Spring Canyon, within sight of Grand Coulee Dam, at 2 p.m. The craggy granite cliffs gave way to low, sandy, sage-covered hills. An endless beach ran along the left bank. Without the cliffs, shady beaches were becoming rare, and I tied up to a big jumble of granite slabs and blocks along the shore for lunch. The pile was just steep enough to offer some shade as I settled in among the boulders. I watched fish swimming in the shady depths while I munched on crackers, peanut butter, a can of tuna, and a can of orange wedges, washed down with a quart of Gatorade. After the break, I motored the last few miles and at about 1 p.m. tied up to the dock at the Spring Canyon boat ramp. I spent the next hour swimming. My wife was right on time at 2 p.m.

Any shade was welcome. The mooring spots were not always the most hospitable but with no wind and away from the current, even an unpromising notch in the rocks allowed me to escape the worst of the heat out in midstream.

Cruising the entire 133-mile length of Lake Roosevelt fulfilled a decades-long dream, but I still feel I’ve only scratched the surface, and nowhere near exhausted all the possibilities for exploration here. SIRIUS, a boat that can be beached at will and easily pushed off again, was a perfect match for the clean, clear, water, the broad blue sky, the coves and creeks, and the endless beaches.![]()

Bob Van Putten and his wife live off-grid deep in the Washington mountains in a straw-bale cottage they built for themselves more than 20 years ago. He is a self-employed systems integration technician specializing in smaller municipal water and wastewater systems. Small boats and being close to the water provide him with dynamic engagement with the real, natural world and force him to live in the moment and continually renew his interest in life.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

I took a hard look a Jim Michalak’s birdhouse designs, but then was pulled away by other more complicated designs. Your wonderful voyage will have me review them again. Any thoughts on the flat bottom Jewelbox vs Scram-pram or IMB?

IMB is my actual building project. I finished all parts about two years ago and looking forward to put her together this year. She has a very spacious cabin for her length.

“Cabin was a greenhouse” – So this was concerning, I have heard of another JM Birdhouse nicknamed “EZ Bake Oven” I believe. But the heat you describe would be disabling in any boat – sitting in the cockpit or “furnace” of the cabin. Thoughts on tinting or reflective material on windows? Insulation on the roof? Bimini or tarp above cabin slot, not sealed, so hot air can exhaust (your pool liner idea is brilliant – thanks for sharing), venting? Or was it simply the three-digits tempts?

Normally I don’t have a problem with the heat, and one reason I selected this design was for the shade the cabin offered. On this trip it was the triple-digit heat, the searing sun and calm that did me in and any other boat would have had the same problem I’m sure. My wife and I spent last winter aboard a 21′ fiberglass sloop in the Florida Keys. Once my wife had to throw me overboard and tow me along through Florida bay, bobbing in my life jacket for a few miles while I cooled off. Once or twice I did the same for her. Sometimes the heat just gets to you.

Hi John!

The only Scram Pram I’ve seen in person is heavily modified from the plans, wears a junk rig and cannot sail to windward at all. It may normally be a good boat but it seems heavy and complicated to me, and I do not care for water ballast. For the same investment I think I’d rather build something else.

I quite like the IMB, but I’ve never seen one. It seems a well thought-out boat and an economical build. I came close to choosing that design myself, but went with the Jewel Box Jr because it used a building technique I was familiar with. I don’t like the mast in the cabin, it complicates the hell out of sealing the cabin rain tight and the mast step is right where you are sleeping, and the off-set mast does make the boat heel more on one tack than the other. So I’d probably build it as a cat-yawl, as I did my Sirius.

As far as the flat bottom vs the multi-chine, I don’t see much advantage of one over the other. The Jewel Box Jr. is tender. The bottom is 4′ wide at best and heavily rockered fore and aft and there is much top-hamper. Given any weight to the wind she sails at enough of an angle that she does not pound. In light winds I often sit to leeward to make her heel some. In certain conditions all three of the above boats will pound, and I think Scram Pram would be worse of all because of her beam. The flat bottom also provides more available flat space within.

Great trip! I remember you building the boat, nice work. I’ve cruised the lower Columbia and plan to spend some time up there eventually.

Quite a trip, and an ideal antidote to modern life.

That’s a trip that been on my list since I got my boat. Envy!

I truly enjoyed this story. The cabin in our Bolger Birdwatcher can also be stifling, even on decidedly un-desert-like Lake Erie. After converting to leeboards I modified the cabin design by making the starboard amidships plexiglass panel removable. Under sail the panel is secured. The removable panel helps ventilate the cabin on the hottest days which are usually also the calmest and most likely motor-dependent. The primary motivation for my modification was increased comfort afforded by the 6′ bench seat after the centerboard trunk was removed, but the additional advantage of cabin cooling is appreciated. The cabin uses smoke-grey plexiglass, but I don’t think that helps with the greenhouse effect.

You don’t need a multimillion-dollar catamaran to have a good adventure. I may have a Michalak Picara in my future.

Great read. Good to learn of this remote lake. Love the boat. I think this is the build? (I may be the last to discover it.) The best thing I learned in this write up is that Titebond can be an alternative for epoxy when gluing. https://forum.woodenboat.com/forum/building-repair/243788-?263545-Jewelbox-Junior=&highlight=

Yep! That’s the build thread at the WoodenBoat forum. You can see I modified the boat heavily from the plans. Titebond III works great anywhere above the waterline, or anywhere at all on a simple skiff for that matter. My La Madalina reviewed in the September issue was built with Titebond II and has held up fine.

Note that I did use epoxy to laminate the double layer bottom on Sirius. I think that’s one place it’s wise to use. I had purchased three quarts of epoxy and the bottom used all that up, so I used polyester resin to fiberglass the bottom.

Interesting fact: All materials came from my local Ace Hardware and Home Depot except for some epoxy, rudder pintles, and rudder drag links which I ordered from Duckworks. I had fiberglass cloth to cover the bottom leftover from an earlier project. The sails were made by David Gray of PolySail International, who was very helpful figuring the new center of effort and proper mast placements for the yawl modification. Total cost including a new Chinese 3.5 H.P. outboard was $1,944.63.

I read this last month and promptly got on Abe Books to order The Venturesome Voyages of Captain Voss. What a great book, thank you for mentioning it in the article. I wish I could be on the Columbia again, but my life has taken a different turn. Keep up the great writing!

~Kees~