These days, I do my cruising in small, open boats. They’re cheaper to build, easier to haul, quicker to set up, and more exciting to sail than big boats. I’ve learned to accept their limitations, happily for the most part, but there are times, like a third straight day pinned down by high winds and driving rain, when what I really want is a small, cozy cabin. I don’t need anything fancy, just a dry place to lay out a sleeping bag and small stove, but the boat still has to be cheap and simple to build, light enough to trailer easily, and enough of a shoal-draft cruiser to pull up to a beach or anchor in knee-deep water.

For that kind of sailing, John Welsford’s Sweet Pea is well worth a look. The name is an allusion to Swee’Pea, the quick-scooting baby from the Popeye comics and cartoons. Welsford originally drew Sweet Pea as a club racer, but his clients also wanted the boat to be suitable for cruising their sparsely inhabited, relatively sheltered home waters. Welsford describes the result as “sport cruising on a budget,” and that’s exactly what Sweet Pea offers: a fairly fast shallow-water cruiser for those who prefer the comforts of a cabin and a portable toilet to a tent and a trowel. The boat could even be a contender in endurance events and adventure races, where a place for the off-watch crew to rest comfortably out of the weather can offer more of an advantage than pure speed.

all photos courtesy of John Welsford

all photos courtesy of John WelsfordThe hull’s flat center panel will keep the Sweet Pea upright on a falling tide.

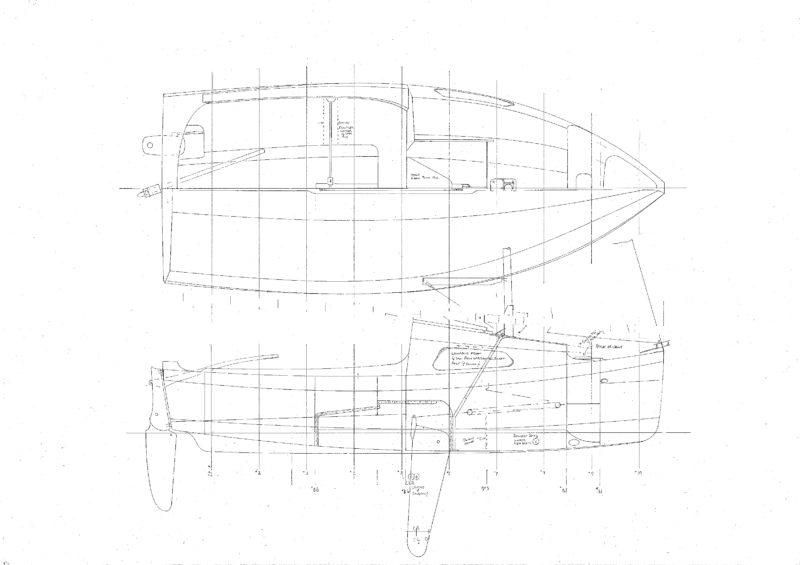

Sweet Pea’s multichined hull is built upright, with hull panels defined by stringers over plywood bulkheads erected on a narrow bottom panel—a simple and inexpensive construction scheme that Welsford often uses. Indeed, Sweet Pea may be simpler than most. Sail Oklahoma! boating festival founder Michael Monies, who built the Sweet Pea described in this article, described the process as “way easier than building a Pathfinder,” a similar-sized Welsford design with no cabin in glued lapstrake plywood, and “about the same as a Scamp,” the popular 11′11″ micro-cruiser designed by Welsford for Small Craft Advisor magazine.

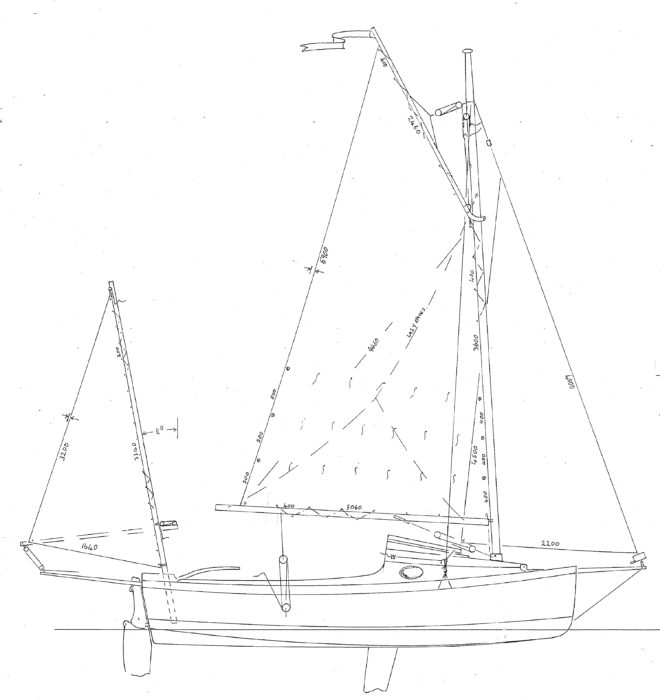

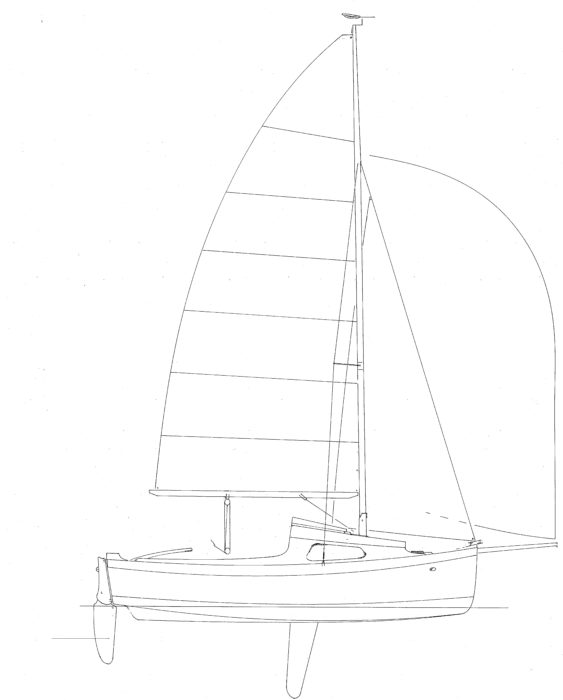

The side panels—three per side, including a narrow sheer plank that adds some tumblehome aft—are 9mm plywood, with the main chine just above the waterline. A large steel centerboard provides plenty of lateral plane, while its weight adds some stability. With its plywood hull, outboard motorwell, and raised-deck cabin, Sweet Pea’s aesthetic is relatively modern rather than ultra-traditional. Two rigs are shown: marconi sloop with spinnaker carrying 198 sq ft of sail, and gaff yawl with 180 sq ft. For a cruising boat, I’d choose the yawl for the advantages a mizzen offers. Those more interested in racing might prefer the bigger sloop rig, although Sweet Pea’s light weight, fine entry, and clean run should have her well over hull speed when reaching or running, even with the smaller yawl rig.

When I first saw John and Ellen Miller’s Sweet Pea on the beach at Sail Oklahoma!, it wasn’t immediately obvious how well it fit my idea of a good small cruising boat. That’s because, like most Welsford boats, it seems far bigger than it is. The cockpit could hold six adults for short daysails—I found it luxurious for two or three when we took it out for a long sail—and the raised-deck cabin offers two full-sized bunks and comfortable sitting headroom, even for skipper John Miller, who is 6′3″. Sweet Pea feels like a 20-footer, well into the category of “big boats” for someone like me, more accustomed to cruising in a 15′ dinghy. And yet, she’s only 17′5″ long, including the short bowsprit, and weighs about 1,100 lbs empty—light enough, no doubt, for a motivated crew to manage the mandatory beach launch (sans trailer) at events such as the WaterTribe Everglades Challenge.

Although the Millers haven’t committed to the Everglades Challenge yet, they did take their newly launched Sweet Pea on the Texas 200, a popular five-day adventure cruise along the Gulf coast of Texas. “I’d never really sailed a small boat in the conditions we had down in Texas,” John Miller says. I know from my own Texas 200 experiences that winds above 20 knots are typical, and there are stretches of open water that can be challenging for small boats. But Sweet Pea handled it quite comfortably, even though the Millers had only sailed their new boat for about two hours total before setting out on the race.

The yawl rig carries 180 sq ft of sail and short, manageable spars.

“I never felt out of control or struggling in any way,” Miller reports. “The boat told you what it wanted to do.” As a result, the Millers sailed along in perfect comfort, averaging about 8 mph according to their GPS, and surfing easily at 10 mph. And with the mizzen for balance, they were able to make their Sweet Pea self-steer—an important consideration for an event where 40-mile days, and long stretches at the tiller, are standard fare. “I don’t think we really touched any of the sheets or the helm all the way from Panther Cut to South Pass,” Miller says, describing one 6-mile close reach. They also discovered that the boat offers plenty of room for cruising. “We lived on it for a week,” Miller tells me. “We could probably go for two weeks on that boat with the two of us.” Having spent a full month aboard a 15’ dinghy this summer, I imagined happily spending six or seven weeks aboard a Sweet Pea. With a supply stop or two, I could easily spend an entire summer aboard—and never get trapped ashore in a sagging, dripping tent. Sweet Pea was starting to sound like my kind of boat.

That impression only got stronger when Ellen Miller invited me out on Sweet Pea for a long, windy sail, along with Michael Monies and designer John Welsford. Launching was simple: Wade out into knee-deep water, manhandle the boat into the wind like an oversized dinghy to raise the sail, and hop aboard. The offshore breeze pushed us off into deeper water, where we dropped the heavy steel centerboard and set off across the lake.

The offset mizzen and the outboard flank Sweet Pea’s rudder. The sides of the footwell are angled provide comfortable footing when the boat heels while under sail.

Once we were moving, my first impression was that I was on a much bigger boat. Sweet Pea is beamy enough to feel quite stable underfoot, and even hard on the wind she’ll heel only so far and then lock in place firmly. Minor triumphs of comfort and ergonomics reveal themselves everywhere aboard, and what might seem to be trivial features make quite a difference. The sides of the cockpit footwell, for example, are perfectly angled to provide a stable footrest as the boat heels. Everyone I talked to who had sailed in the Millers’ Sweet Pea noticed this, and raved about how comfortable it was. The seats themselves are wide and comfortable, and visibility from the helm is excellent, with the cabintop low enough to see over easily. The tiller felt light and responsive, needing only fingertip control.

Even on a broad reach we were able to play the mizzen to make the boat steer itself, virtually hands-off. When we hit planing mode, the shift was so subtle that Welsford had to point it out the first time. The subtle smoothness of that transition is an intentional feature of the design; Sweet Pea’s rocker is designed to lift the bow and slip up on plane easily, rather than “popping out” by brute force when the wind powers up enough to overcome the bow wave. “It sails wonderfully,” John Miller told me, summing up Sweet Pea’s performance in the Texas 200. “It’s way more capable than I realized at first. I would feel comfortable taking it on some pretty big water.” Very quickly, I found myself agreeing. Sweet Pea sails as if she wants to take care of her crew.

Still under construction, this Sweet Pea cabin awaits its roof. The benches flanking the centerboard trunk serve as full-length bunks.

Of course, no boat is perfect. Sweet Pea’s cabin, comfortable as it is at anchor, is less comfortable while sailing. The big centerboard restricts legroom, and an angle of heel that feels perfectly comfortable in the cockpit feels much more extreme below. Everything feels much more extreme below, with the cabin magnifying even the smallest sounds; a routine tack can sound like an emergency. The centerboard tackle runs down the cabin’s centerline, making it difficult to switch sides during tacks (at rest that’s not a problem, because the tackle can be temporarily removed, and replaced with a bolt to hold the board in place).

But those complaints are minor, and every skipper will find his own way of dealing with them. One issue that can’t be avoided, though, is setup time, which is far greater than the time needed for a 15′ open boat with an unstayed rig. “You’ve got two to two-and-a-half hours of setup and takedown for however much time you spend on the water,” John Miller told me. Which means that unless you plan to keep a Sweet Pea on the water, either on a mooring or in a slip, it’s not a good choice for a boat that will be dry-sailed and trailered. But the solution to that problem seems especially simple to me: just set up the boat once in spring, and spend your entire summer cruising. Simple enough.![]()

Tom Pamperin writes regularly for WoodenBoat. His first book, Jagular Goes Everywhere: (mis)Adventures in a $300 Sailboat, was released in November 2014.

Sweet Pea Particulars

[table]

LOA/17′ 5″

Beam/7′ 4″

DRAFT

Board up/8″

Board down/4′ 5″

SAIL AREA

Sloop/198 sq ft

Yawl/180 sq ft

[/table]

The cruising yawl rig has short manageable spars and sails that are easily reefed.

The sloop rig’s 198 sq ft of sail will bring the Sweet Pea up on a plane in a reach or a run.

The plans call for 9mm plywood skin over the chines and plywood bulkheads, a simple structure quickly constructed. The cockpit will sea six and the cabin will seat four and sleep two.

Plans for Sweet Pea are available from Duckworks Boat Builders Supply, or from the designer, John Welsford.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

I’m looking for a second boat to build after finishing a Martha’s Tender. A Sweet Pea with the Gaff Yawl rig just looks like it would be the perfect choice for me. I really like the beaminess of the boat; my John Leather designed Oyster is that way and brings tremendous stability and the capacity to carry six people. I also like the simpler construction of building around the bulkheads rather than molds. That will save a lot of time and I won’t get stuck with a stack of molds after construction. I am also impressed with the Sweat Pea’s sailing ability. It would match my style for sailing in all kinds of weather. Nice article—it has me hooked!

Dick G

Tom, excellent article on Sweet Pea. Having watched her being built out in the Boat Palace, I can say it is a joy to see her shining and on the water. While she is indeed somewhat more modern in appearance than we are used to seeing in John Welsford’s boats, she is still a Welsford. There is no escaping that classic Welsford look. I always knew she was a keeper for the sort of coastal sailing most of us do but offering features and stability we don’t always have in small boats we build.

I see John Welsford’s influence on Scamp. Both the Sweat Pea and the Scamp are amazing designs for such small craft. I can imagine downgrading from 21ft sometime in the future.

I’m late to this conversation, but thanks, everyone, for your comments and kind words. Sweet Pea—yeah, I really liked it. Seems like a comfortable and fast boat, a cabin boat I could imagine myself building someday (relatively simple to build) if I ever go back to cabins. I’m so glad I got the chance to go out for a long afternoon sail with Mike and John at Oklahoma.