all photographs by Dave Hupke

all photographs by Dave HupkeDave’s canoe is as much at home on a muddy creek bank as it is in an art gallery—it was shown at the Galesburg Civic Art Center. Dave, a professional photographer, is no stranger to the art world.

Six years ago, a nearly fatal injury landed Dave Hupke in the hospital. While his life hung in the balance, he imagined what he would do if he were to have the good fortune to live beyond the age of 46. As a teen, he had been a Boy Scout guide at the Charles L. Sommers Wilderness Canoe Base in Ely, Minnesota, and later, as an Eagle Scout, led trips through the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. He had fond memories of wilderness paddling and of the beauty of cedar-strip canoes. He decided that if he walked out of the hospital he’d build a canoe.

David’s father, Horst Hupke, had the tools and his skills as a woodworker to hasten progress on the canoe project. Note the splitter secured by the smallest clamp. It holds the work to the fence and keeps the cedar from binding on the saw blade.

Horst’s spindle shaper, equipped with cutters for matching beads (shown here) and coves, made it possible to do quick and accurate milling of the strips.

A month passed and although Dave was weak, scarred, and had lost 30 pounds, he had survived. He had a long road to recovery before he could begin work on the canoe. Three-and-a-half years later, he had his strength back and was back at work. He had the time and the energy to devote to building his canoe.

His father, Horst, had been a craftsman in northern Germany before immigrating to the States, and is, despite his 82 years, an energetic and adroit woodworker. Horst was eager to lend his support to Dave’s project and offered up his woodworking expertise, his woodshop, and his garage.

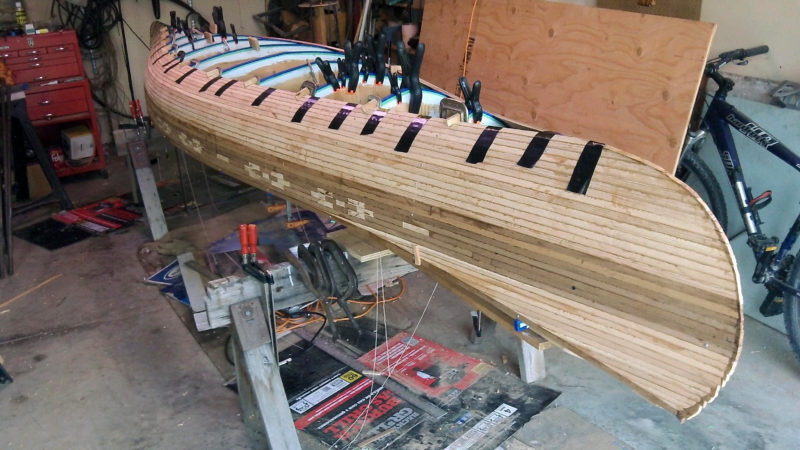

Dave and Horst used duct tape to hold the strips to each other and clamps and wedges to hold them to the molds, avoiding the use of staples and the holes they leave after they’re removed.

Dave searched the web for plans and came upon the canoes of Ray Klebba of White Salmon Boat Works in the town of White Salmon, Washington. Ray’s 17′ Kenosha design was very much like the canoes Dave had admired in his days as a Scout. Dave ordered a set of plans and even before they arrived, he and Horst started milling western red cedar into cove-and-bead strips. The 18′ planks were too long to handle in Horst’s shop, so they moved the tablesaw and then the shaper out to the driveway. A set of shop-made fences, hold-downs, and guides assured the strips were milled accurately and uniformly.

Dave’s woodburned insignia included two bottle caps to remind him of the Root Beer Lady of Knife Lake.

With the milling finished, Dave sorted the strips by color, from blond to chocolate brown. He added some birch to the building materials for bright accents and to pay his respects to the birchbark ancestors of his canoe.

With the hull ‘glassed, the canoe is ready for the gunwales, seats, and decks.

Dave and Horst worked together building the strongback, setting up the forms, and stripping the hull. With the planking complete, Dave designed an insignia for the bow of his canoe. The woodburning design included a hoop and feathers to honor the Native American origins of canoes. At the top Dave added a bottle cap, acknowledging The Root Beer Lady, Dorothy Molter. Molter made root beer in her cabin on the shores of Knife Lake and sold it to countless canoeists who paddled through what became the Boundary Waters Canoe Area (BWCA). When the BWCA was established as a wilderness area, Molter would have been forced to move, but the outcry from loyal canoeists led to permission for her to stay. She remained in her lakeside home until her death in 1986. Inside the outline of the bottle cap are the joined letters, HR. They stand for “Hol-Ry,” a greeting used by the canoeists of the Sommers Wilderness Canoe Base. Hol-Ry was the name of a rye cracker, made in a Duluth bakery, that didn’t break when stuffed in a pack, and didn’t spoil during backcountry voyages.

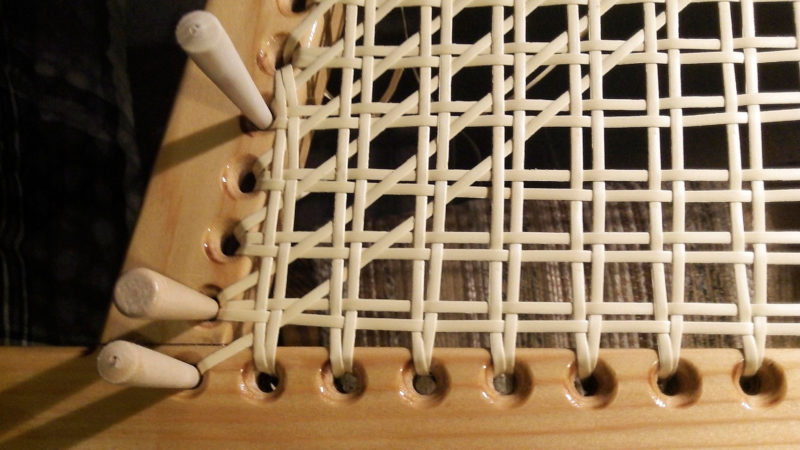

Rather than use pre-woven seat caning, Dave did the weaving himself, a job that takes time, patience, and focus.

Dave made two paddles for the canoe, one straight and the other bent-shaft, and decorated them with the same insignia he put on the canoe. He and his friend Andy Look won the wooden canoe division of the 13.5-mile Abe’s River Race on the Sangamon River in Illinois.

While the insignia on Dave’s canoe bears symbols of a fondly remembered past, the canoe itself grew out of hope in the face of an uncertain future. What better way could there be for Dave to celebrate a second chance at life than to take to the water in a wooden boat he built with his father?![]()

Have you recently launched a boat? Please email us. We’d like to hear about it and share your story with other Small Boats Monthly readers.

A beautiful story, and very inspiring! Congratulations on a job very well done, indeed, and a great outlook on life.

I am inspired by Dave’s work with his dad. I have built several boats, without, mercifully, Dave’s impetus to build. I am delighted to read that he chose his own history and used a wooden boat to celebrate that and his future. Good on ya, Dave!

Wonderful memories of Dorothy.