The east side of the Bustard Islands was all shoals and breakers, with a broad band of granite shelves and outcroppings stretching half a mile or more offshore. Typical for Georgian Bay, I knew, where the safest routes run well outside to avoid the rocks, or follow the well-buoyed passages of the charted small-craft route that traverses Georgian Bay’s eastern shoreline.

Here in the Thirty Thousand Islands region, only kayaks and canoes—or a sail-and-oar cruiser with her board and rudder up—can manage to sneak through to the shore in most places. And even boats like my as-yet-unnamed Don Kurylko–designed Alaska beach cruiser have to pick their way carefully. Passing through the northern end of the Bustard Islands on my approach from the west, I had seen a few cottages and sailed past half a dozen larger boats in the main anchorage between Tie Island and Strawberry Island. Out here on the east side of the Bustards I was completely on my own.

photographs by the author

photographs by the authorLike most of Georgian Bay’s eastern shore, the Bustard Islands are a compact collection of long narrow channels running parallel to each other, divided by low ridges of the Canadian Shield’s exposed granite topped by mature white pines. After I made it through the wide band of rocky shoals offshore, I threaded my way into Tanvat Island’s east side.

Holding a close reach well offshore, I eased the sheet until we were barely moving, fore-reaching along at half a knot. From a mile away it was almost impossible to identify any features of the low-lying islands behind the band of shoals, but I made my best guess at identifying an inlet that might mark the channel I wanted and took a bearing with my hand compass. Things would become clearer as I got closer, but I wanted to have at least some idea where I was headed before starting in.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

On the chart, Tanvat Island is a spiderweb of long-fingered inlets and peninsulas reaching out to the north, south, and east; long ridges of pine and granite surrounded by hundreds of smaller islands that made it difficult to recognize the underlying shape. It looked like I should be able to skirt along the northern edge of the shoals and work close to shore in mostly open water. Worth a try, at least. I sheeted in to gather speed and pushed the tiller over to put the boat on a port tack, then steered toward the east side of Tanvat Island, watching the compass closely. I was trying for a course just south of west, but soon I was detouring around slabs of granite lying just beneath the surface and dodging half-submerged rocks almost completely hidden in the waves. After a few minutes, I gave up. “Mostly open water” or not, it would be foolish to try to sneak in any closer under sail. Turning into the wind, I dropped the sail and unclipped the halyard. It would be oars from here.

I pulled up the centerboard and rudder and slid the oars into the locks, then glanced again at the chart as we drifted slowly toward shore. I had managed to judge my entry well, despite my somewhat rough combination of eyeball navigation and compass bearings. At least, I thought I had judged well. But the chart might as well have been an inkblot test, a convoluted scrawling of rocks, islands, and narrow channels that twisted around each other like snakes crawling through a maze. When I put the tip of my finger down about where I thought I was, it covered more than a dozen islands. I wasn’t about to put any money on which one was which.

It didn’t really matter, anyway. I was almost through the reefs and safe along the east side of Tanvat Island—if I could manage to figure out which one it was. The narrow passage opening before me was lined with tall pines and granite slabs, and surrounded by a chaotic jumble of rocks, islands, hidden bays, and gnarled peninsulas. Was this the channel I had hoped to hit? I’d find out soon enough. Either way, I had reached the Bustards. It had taken me four days and a hundred miles, but finally, I was here. I moved to the aft thwart so I could row while facing forward—an advantage in avoiding the countless uncharted rocks and shoals I knew I’d encounter here—and made my way slowly deeper into the maze.

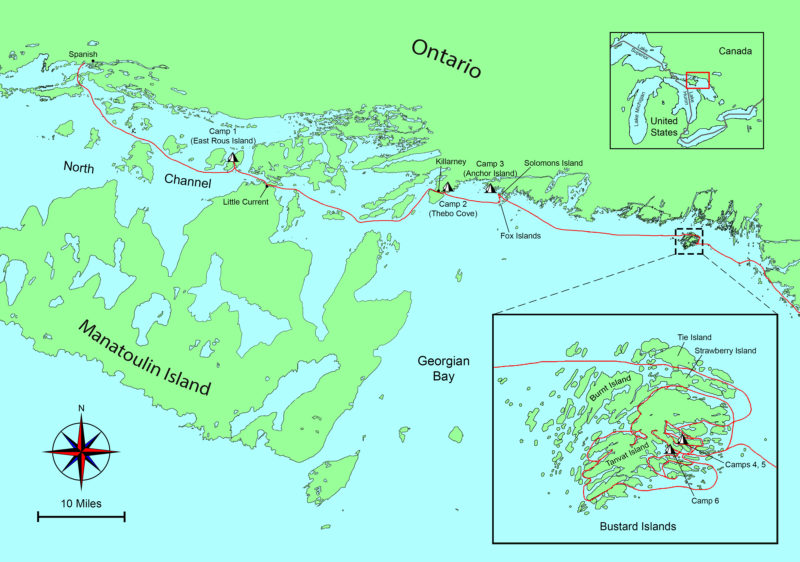

I had launched in the center of the North Channel, at the municipal marina in the small town of Spanish, Ontario, a ten-hour drive from home. Another four or five hours in the car would have gotten me to Georgian Bay two days sooner, but from my previous visits I knew Spanish had what I needed: a good ramp, showers, a laundromat, and, most important of all, hassle-free parking for a car and trailer for weeks at a time. Although I wanted as much time in Georgian Bay as I could get, that alone made Spanish a worthwhile trade-off.

After spending the first night on East Rous Island I woke to the flat calm of a typical North Channel summer morning. Three hours later, after rowing 6 miles and stopping briefly in the town of Little Current, a slight breeze arrived and I could stow the oars and raise the sail.

I had covered 60 miles in the first two days, broad-reaching on the starboard tack for hours on end, bypassing towns and marinas and overnighting in out-of-the-way backwaters, places too shallow or too small to see much traffic. At East Rous Island, a few miles west of Little Current, I anchored in knee-deep water outside the crowded main anchorage and slept on the Alaska’s full-width sleeping platform; at Thebo Cove a mile outside Killarney, I tied to shore and set up a freestanding tent on a granite slab.

This rocky beach on the west side of West Fox Island, 7 miles east of Killarney, offers a convenient place to land a boat, but lies completely exposed to the prevailing westerlies. Overnighting here is best left to kayaks and canoes—lightweight boats that can be carried up the beach. I had lunch here and headed north to spend the night in better protected waters.

The third day had brought me 7 miles east of Killarney to the Fox Islands, a favorite destination from earlier trips. Here, finally, was Georgian Bay, wild and rocky and filled with possibilities: high granite domes rising from the water, broad smooth slabs of Canadian shield granite sweeping up to jagged skylines of tall pines, trees that have withstood the prevailing westerlies for so long that they remain forever bent and twisted toward the east as if reaching out in supplication to some unseen power. After a lunch ashore on West Fox, I set out again, ghosting along in winds so light that I could barely feel the breeze.

A mile north of West Fox Island, the cluster of islets around Anchor Island and Solomons Island offers dozens of protected campsites for small boats. With an open boat, sleeping aboard is a good option only if you have foolproof mosquito netting. I opted to spend the nights in my tent.

Well, so be it. I’ve learned to enjoy what the day gives you rather than worrying about what it does not. This would be no 30-mile day. Instead, I worked my way slowly northward toward a cluster of islands only a mile away. With the wind behind me, and rocks all around, I sailed carefully, centerboard up, through cliff-lined channels less than a boat-length wide, sneaking through passages barely deep enough for my boat’s 7″ draft. And there, in a tiny shoal-draft backwater tucked in between Anchor Island and Solomons Island, I tied the boat to shore and unloaded my gear. This would be camp for the night. An afternoon ashore, scrambling among the rocks and climbing to the island’s tall summit, a long swim in the pleasantly cool water, and a quiet night at camp. After two days in the boat, it was exactly what I needed.

But now, 30 miles farther on and ready to make my landfall in the Bustards, I needed to figure out where I was. With no GPS—I try to avoid machines that purport to do our thinking for us—that might not be easy. But I knew it was almost always possible, even in a complicated setting like this. Here. The channel I was following split into two branches, then split again. I looked closely at the chart, turned it to align with the compass. A cluster of rocky islands here, a lone rock there. This was it—I had managed to find the passage I had been looking for. All I had to do now was follow the channel’s right-hand shore—Tanvat Island, I was fairly sure—through every twist and turn, as if working my way through a labyrinth with one hand on the wall. I kept rowing. A few more rocks and islands that matched the chart precisely confirmed it. Amazingly enough, I knew exactly where I was.

My fourth day began with cold rain and a strong breeze. Fortunately, the boat’s boomless standing lugsail is easily reefed: simply roll up the foot and tie it in place. With the first or second reef tied in, the boat performs well to windward; the deep third reef keeps things in control when running for shelter.

Twenty minutes later, rowing along a long narrow bay that ran between two ridges of granite topped with dark pines, I found my campsite: a broad smooth slab of gray stone that swept up from the water to a stand of gnarled pines above. Behind the trees, the ridge dropped down again to a dark pond dotted with white-flowered lily pads. The water here, so deep inside the maze, was perfectly calm with only the slight wake from our passage rippling through the reflection of the rock and sky and trees. I shipped the oars 10 yards out and let the boat glide slowly into shore, then stepped out into knee-deep water and tied the painter to a beaver-chewed stump at the water’s edge.

It had been another long day—30 miles of non-stop sailing on a close reach, and a half-hour of rowing. There was plenty of daylight left, but I felt no need to go farther. Instead, I stood barefoot on the stone and felt the rough texture of the granite, the curling lichen underfoot. Breathing deeply, I listened to the world around me. It was not silence, not completely, but a quiet stillness that seemed to hang heavy in the air. A whisper of shifting branches overhead, the faint ripple of water. And somewhere, a moment later, the call of a loon. I unstrapped my dry bags from the boat and carried them to shore.

I woke the next morning to a world blurred by gray mist and shrouded in silence. The water was still and dark at the foot of the rocks, a liquid mirror unruffled by the faintest hint of motion. Far out at the eastern edge of the islands, fog lay so thick on Georgian Bay that there was no horizon, no up, no down. It was no day for offshore sailing, but it would be perfect for exploring the maze of backwaters, narrow passages, hidden coves, and islands that made up the east side of the Bustards.

Moving as quietly as I could, I got my raincoat and water bottle and set them in the boat, then untied from shore. I stepped aboard with a gentle push, easing myself onto on the rowing thwart as the boat slid away from shore. As I lowered the oars gently into the water, I realized that I hadn’t even bothered with breakfast.

The fog held through the morning, painting the world in a palette of muted grays and blacks all around me as I rowed. A hundred oar strokes, a hundred paintings. The foreground of each scene came into sharp focus as I moved through it, the background forever hazy and indistinct. A vague darkness of pines; an oddly serrated slab of rock revealed itself to be a line of gulls standing and muttering to themselves as I rowed closer. From overhead came the rattling cry of a sandhill crane.

Hidden in the complex web of Tanvat Island’s surrounding maze is a wealth of potential campsites and anchorages. This perfectly sheltered inlet, my base camp for two nights, was tucked well back inside the Bustards, more than a half mile from the open waters of Georgian Bay.

My 18′ Alaska had been designed with exactly this in mind. With its Whitehall lines and narrow double-ended waterline, it was a decent sailer, but a flawless pulling boat. Built of 1/2″ planks, edge-nailed and glued—traditional strip planking—she was heavy enough to hold the momentum of each stroke. The oar blades dropped silently into the water, again and again, and glided through the maze with little effort and even less noise. At times the channel I was following pinched down to a passage so narrow there was no room to row, but the Alaska glided through easily, the hull’s weight preserving forward motion while the long keel kept her straight.

The layout of the maze become clearer in my head as I explored, my perceptions shifting to bring the chart and the world around me in line with each other. I had camped in the center of a long irregular peninsula that stuck out from the east side of Tanvat Island like a pair of weirdly twisted, frog-like legs. North of the peninsula was a large bay filled with so many islands that it was hard to recognize that it was, in fact, a large bay. By lunchtime I had explored it thoroughly under oars, making the discovery that the “peninsula” I had camped on was, in fact, an island—water levels were so high that a small circular inlet just west of camp had become a passage through to the other side. At least, a passage for boats with extreme shoal draft. Even the Alaska managed to scrape her keel as I slipped past.

A foggy morning on Tanvat Island’s east side inspired a lengthy rowing expedition before breakfast. On the chart, this bay was a dead end, but high water levels on Lake Huron and Georgian Bay allowed me to row all the way through and out the other side.

I returned to camp for lunch, a meal of red beans and rice I had prepped in my Thermos the night before. After eating, I set out again, this time following the southern edge of the peninsula. The day was still hazy and windless, the water flat and dark. I followed the shoreline of the peninsula until I reached its base, where I rowed far back into a fish-hook bay filled with lily pads, the shores strewn with beaver-gnawed branches. I had rowed 2 miles to get here, but the hook of the bay was dug so deeply into the island that a ridge of granite a few yards wide was all that separated me from the north side where I had spent the morning exploring. I had rowed for several hours and was barely a quarter of a mile from my campsite.

The Bustards, I realized, were a world of infinite possibilities.

Two hours after leaving camp, rowing steadily all the while along a circuitous route, I was still less than a mile from camp as the crow flies. The Bustard Islands hold more possibilities per mile than any other cruising area I’ve experienced.

One of the great joys of traveling by one’s self, I’ve learned, is that much of the need to plan ahead is negated. The solo traveler—the solo sailor—is free to act on a whim, and can keep all options open. By the time I had eaten a quick bowl of oatmeal the next morning, I still had no idea how I would spend the day. I suppose that many people would find that level of uncertainty unsettling, or annoying. Perhaps even foolish. I find it liberating.

I loaded everything into the boat—tent and gear, food and sailing rig—to keep my options open. First I’d row out to the mouth of the bay, where I could get a look at conditions on Georgian Bay proper. If the wind was good to continue south and east along the coast, I’d be ready to sail. If not—

Well, if not, I’d find something else to do. Just to be on the safe side, I surveyed the crew about my plan’s lack of specificity. No one objected. Taking a last look around camp to make sure I hadn’t forgotten anything, I rowed slowly out the channel toward the open water beyond. After ten strokes, the granite slab where I had set up my tent had vanished into the mist.

My technique for rowing the channels in the Bustard Islands was to keep the boat running straight with the help of a bungee-and-cord tiller tender and go fast enough to coast through the narrow spots.

As soon as I reached the edge of the bay, I knew that I wouldn’t be heading offshore. Fog had settled so thickly on the open waters of Georgian Bay that I doubted I’d be able to see the faintest hint of the Bustards from a hundred yards offshore. A chart and compass would suffice to get me to the next landfall, I knew—the ominously named Dead Island 3 miles to the east, where First Nations tribes had long ago interred their dead in the treetops, according to some sources I’d read—but it wouldn’t be the height of good judgment.

Besides, I was far from done here. On my only previous trip here, I had only stayed one night. This time I wanted more. But more what? I had already explored most of the eastern side of Tanvat Island, and retracing yesterday’s paths seemed less interesting than trying something new. I pulled out the chart. Tanvat Island, the largest in the Bustards, lay spread out across the page in two monstrous, squid-like lobes separated by a narrow isthmus where a deep bay cut into the shore on the western side. The area around Burnt Island just to the west housed a number of cottages, and the Bustard Island Headquarters for French River Provincial Park. There’d be other boats, other people. Burnt Island was, in other words, better to avoid.

The pond behind my Tanvat Island campsite—you can see my yellow tent through the fog—was too shallow for the boat’s 7” draft, and the entrance too narrow for the hull. It was a rare dead end.

But Tanvat Island itself? Possibilities. Tracing my finger around its convoluted outline, I wondered about a circumnavigation. But Tanvat’s northern end was pinched so tightly together with Strawberry Island that their outlines on the chart were touching. And Tanvat’s southern end was an endless scattering of rocks and shoals. Then too, there was a wide band of blue—the color used to indicate depths too shallow to bother marking—surrounding the entire island. I knew from yesterday’s explorations that not even my Alaska could always float across that blue band, and at 250 lbs for the empty hull, I wasn’t going to portage her. With water levels as high as they were, I thought my chances were good, but there would be no guarantees.

Gripping the oars lightly, I turned the boat north along the east side of Tanvat Island to begin—a counterclockwise circumnavigation. Or an ignominious failure. Either way, it’d be a good day.

The interior waterways of the Bustard Islands seem far removed from the open waters and offshore passages of Georgian Bay, but a good sail-and-oar cruising boat is equally at home in either world.

By late afternoon I had returned to the east side of Tanvat Island and pulled into the wide bay just south of my previous campsite, circumnavigation complete. I had seen no one. No one, that is, except for a few beavers, a pine marten (the first I’d ever seen in the wild), a northern water snake, a blue heron, a curious mink who swam out to the boat to stare wide-eyed at me for a moment before vanishing underwater, and an eastern massasauga rattlesnake that sidewinded its way across the surface of the water and crawled up onto the rocky dome where I had stopped for lunch.

The best thing about a long cruise is that there’s never any reason to hurry. With the fog gone, I enjoyed a quiet evening in camp after my all-day circumnavigation of Tanvat Island.

In the center of the bay I made camp at a cluster of three islands—in my head I had taken to calling them the Three Brothers—and rigged lines to keep the boat in shallow water without banging against the rocks. After a long swim and another Thermos-cooked supper, followed by a second course of instant mashed potatoes, I set up my tent on the island’s eastern summit, a bare granite dome overlooking the bay from ten feet above.

On my last night in the Bustards, I chose a tent site that faced east over relatively open water. As a result, the morning light woke me well before the sun cleared the horizon.

The sun was setting behind me, and the sky filled slowly with pinks and blues and wisps of purple clouds. The reflection in the still waters below was no less vivid. A sandhill crane flew past, wide wings flapping silently. Its rattling call was answered by another from deep within the dark pines of Tanvat Island. And then, silence.

Looking east from camp on my final morning in the Bustard Islands, it was easy to see a clear route out to the open waters of Georgian Bay to continue my journey.

I stood for a long time watching the sky grow slowly darker, until the first stars began to appear overhead. Tomorrow would be a fine sailing day and in the morning I’d be heading south along the shores of the Thirty Thousand Islands, sailing deeper into Georgian Bay. Being fogged in among the Bastards had seemed like an interruption at first, but the delay had forced upon me a mist-muted world where time and distance had become irrelevant, ambiguous, uncertain. For three days I had moved through a veiled, endless now, where each stroke of the oars only held me more firmly in place in the moment. Whatever lay beyond the mist remained out of reach no matter how far I rowed. When I woke the next morning to blue skies and bright sunlight, the Bustards felt like another world entirely, one made finite by its startling clarity.![]()

Tom Pamperin is a freelance writer who lives in northwestern Wisconsin. He spends his summers cruising small boats throughout Wisconsin, the North Channel, and along the Texas coast. He is a frequent contributor to Small Boats Monthly and WoodenBoat.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

I love your article, and the Bustards are dear to my heart. Please be aware though that the Bustard Islands are part of the French River Provincial Park. Camping is only permitted in designated campsites and there is a fee per night to camp. The area is being scarred by by fire pits which leave unrepairable scars on the rocks. Enjoy the Bustards but please abide by the rules of the park.

The question of camping permits for small-boat cruising is a difficult one for me. I value the conversation and preservation efforts that permits are designed to sustain, but at the same time some permit requirements can pose difficulties.

In my experience, a permit often demands a fixed schedule, which can impose a degree of risk that I am not comfortable with. The decisions I make when traveling in a small open boat are dependent on weather conditions, visibility, and sea state. If the itinerary I’ve registered demands that I must go to a particular campsite on a particular day, but sailing to it is not safe in my judgment, then I reluctantly have to choose between breaking the rules or doing something foolish.

My own uneasy compromise, one I have arrived at after much thought and soul searching, has been to eschew official permits and keep a very low profile, including the use of minimum impact camping practices: no fires, camp on exposed bedrock, proper waste disposal, etc. I understand that’s not something everyone is comfortable with, and have no wish to persuade anyone to adopt my views. But when I am in a small boat, especially when cruising in remote or semi-remote areas, avoiding a the imposition of a rigid schedule is, I firmly believe, a significant element of my personal safety.

Having sailed the French River Delta and the Bustard Islands when no permit was required, I have the same concern as Tom. I also cherish the area but unless you use a base camp, we generally have no idea where we will be at the end of the day! It is often unlikely one can make it out to the Bustards as the weather will decide! We did make it a couple days to explore. Major Island was our camp on returning to the Delta and was wonderful but “had” a garbage dump in the ravine behind our camp! We did not add to it and no doubt it is cleaned up by now, to the credit of park staff! Here another storm had us exploring more of the back waters rather than heading south in the open. Love the area and I always buy the Provincial Park Pass (great value) but hesitate to be bound to a scheduled camp. These days it is less an issue as we generally sleep on our boat but for others it does pose problems that perhaps a solution could be found.

Best,

Roy

Roy, good to hear from you again! Thanks for sharing your thoughts, because I’m very interested to hear how others deal with the permits issue. I’d be happy to pay the fees but am not willing to commit to a rigid schedule. And with sail-and-oar boaters making up such a vanishingly small portion of visitors, I’m hesitant to talk to rangers ahead of time because I’m skeptical about the bureaucracy’s willingness to make exceptions.

Anchoring out and sleeping aboard might be a way around the letter of the law, if not the spirit.

Tom, my little Aussie battler mate from Queensland,Paul Hernes, who commissioned the design of Phoenix and built the first one, alerted me yesterday to your latest literary nautical offering which I have just finished re-living with you via another of your wonderfully flowing accounts. Your choice of photos really brings the true feel of your surroundings and are a welcome addition that helps the narrative flow and makes me feel as though I’m along for the adventure. A welcome addition to your growing collection of most enjoyable true tales. It also showcased the positive attributes of your great boat which looks to suit your purpose admirably. I look forward to reading about your next adventure. Most enjoyable. Thank you.

Al

Al,

I’m sorry for the late reply. Somehow I lost track of my notifications. Thanks very much for the kind words. Thank Paul H. for me for getting such a great design out of Ross! The Alaska is great, too.

Tom, how fun it was to run into each other in Killarney in July. I was just launching my boat SOUTHERN CROSS and there you were aboard your new ride. I concur with your take on permits for that area. I have just penned a column for Small Craft Advisor titled “Without a Trace.” It addresses the leave-no-trace question and that is precisely how I cruise—as a good citizen. We have a fine opportunity to be such good citizens precisely because we sail small. Good seeing ya mate.

Howard,

Thanks for the note. Yes, it was great to run into you and SOUTHERN CROSS, and quite a surprise as I don’t see many unconventional homebuilt small cruising boats on the Great Lakes. None, really, before running into you all this summer.

The leave-no-trace ethic is an important topic for this kind of cruising. Small boats do lend themselves to keeping a very low profile that I really appreciate.

If you do not take control over your time and your life, other people will gobble it up. If you don’t prioritize your self, you start falling lower and lower on your list.

Cap’n Rick, Port of Lewes, Delaware – a Verlen Kruger kind of paddler!

Rick,

I met Valerie Fons in Wisconsin a couple of summers ago, in the little paddling museum (really a Verlen Kruger museum) that she runs on Washington Island in Door County. She signed a copy of her book Keep It Moving: Baja by canoe, (about paddling around Baja with Verlen) to me. I hadn’t really known much about her and Verlen before that. Serious adventures they’ve had. Georgian Bay would be (is) just as good for paddling as it is for sail and oar.

Tom

Well, Tom, as is always the case, your writing and photography have transported me to a good place. For that I thank you sincerely. The pleasure your writing evokes is multi-faceted, because in addition to encouraging me to continue with my chosen form of sailing, it confirms my own convictions about small-craft design and use. Wonderful, satisfying writing.

Ross,

thanks for your kind words, and I’m glad you enjoyed the article (and glad we have Small Boats Monthly to publish it!) I sometimes almost regret ever finishing my Alaska, since I don’t have a reason to borrow my brother’s Phoenix III* anymore. Life is tough, eh?

Tom

(*a Ross Lillistone design. Ed.)

Could so easily be the Baltic. Amazing!

Roger,

I’d love to do a Baltic cruise—not much for tides there either, I suppose? That certainly simplifies things. I’ve been eyeing up the coast of Finland for years now. But of course the Great Lakes are so much closer for me…

By the way, thanks for all the videos you’ve shared about your own cruising. I’ve really enjoyed them!

Tom

Tom, I ‘m working my way through my new subscription here and, as always, enjoying your trip/trips through your words, great photos, and video!

Thanks for feeding my dreams!

Robert,

Thanks for the kind words. This was definitely one of my favorite trips ever; it was fun to write about. Let’s hope you translate dreams to reality with your own visit to Georgian Bay at some point!

Tom,

Dreams and reality are becoming one! Just noticed Roger Barnes above – both you and he have moved me to the point of choosing the Ilur, which is now 10′ from me in my garage! Last weekend I was with three gents sailing on Chester River, Maryland, and “feeling” what it is you all are going after. Been a long time since I’ve just plain chilled to that level and felt something close to actual total tranquility, inside and out. On the boat for 22 hours and…so what? Loved it. Gratitude also goes out to the Old Bay Club gents.

Wonderful read and pics; reminds me of the best of numerous kayak trips off the west coast of Vancouver Island, while showing the enchantments of a sail-and-oar cruiser.

Thank you.

Wonderful prose, beautiful pictures allow me to venture vicariously along on your adventures. Hope to sail up there someday.

Thank you ! And Chris for this forum.

Glad you have your Alaska now. Really enjoyed your article and pictures.

Hi,

I was amazed at the sheer beauty of the area I never knew. Great photos and boat. I am curious about the weight of your boat as I am looking to build but can’t find any weight

Thanks,

H

The study plans for Don Kurylko’s Alaska list the approximate hull weight as 300 lbs.

—Ed.

I’ve never weighed my Alaska, but 300 lbs sounds about right, Huw.

In practical terms, it’s so heavy that my wife and I had a hard time lifting the boat off the trailer and flipping it over for re-painting a year or so back. We managed it with just the two of us, but it wasn’t easy. It’s definitely heavy enough that rolling it up onto a beach is not a one-person operation (especially since the zero-rocker keel makes it even harder). Two people can lift and carry it for short distances when the hull is empty, but I wouldn’t want to have to move it very far.

Tom