The Droleen, a 12′ lapstrake catboat, was designed in 1896 by W. Ogilvy of Bray, a town on the east coast of Ireland. It was intended to be launched off a stony beach and to be sailed “in any weather, plenty of wind and sea—not infrequently encountered off the coast of Bray,” according to H.C. Folkard’s 1906 book, Sailing Boats from Around the World.

Eight boats were built—some, if not at all, by Mr. Foley of Ringsend, Dublin—but it is thought that the development of the class was hampered when some of the original owners, who were in the British Army, were called away to fight in the Boer War (1899–1902) in South Africa. There was, however, some class racing up until the First World War, after which the boats gradually disappeared. None survive today.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorThe trailing edge of the 3/16″ galvanized steel centerplate is fully exposed when retracted in the open-topped trunk.

The plans survived somehow and in 1996 they were redrafted by the renowned naval architect and small-boat designer, George O’Brien Kennedy. This allowed the Bray Droleen Heritage Association—founded in 2013 and led by the late Frank de Groot—to build two new boats, the first of which was launched at an Old Gaffers Association event on Dublin’s River Liffey in 2014. When Irishman Michael Weed enrolled at the Boat Building Academy (BBA) in Lyme Regis, U.K., he was keen to build one. He managed to get hold of a set of drawings from Jim Horgan, who runs the Galway School of Boat Building on the west coast of Ireland.

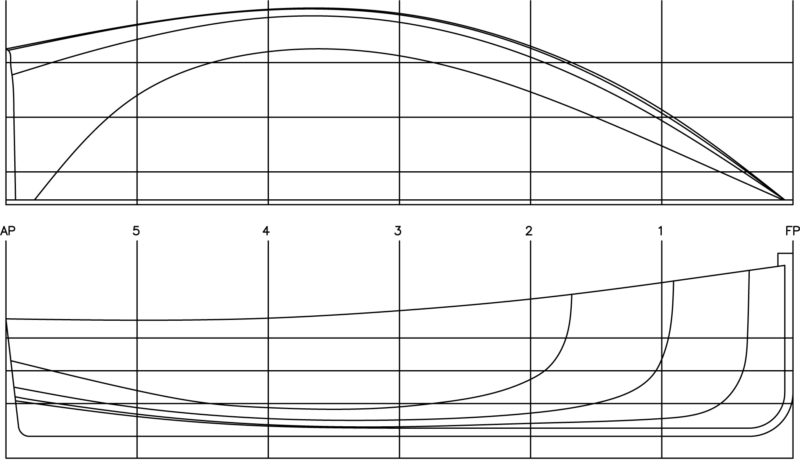

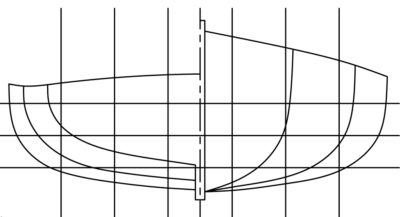

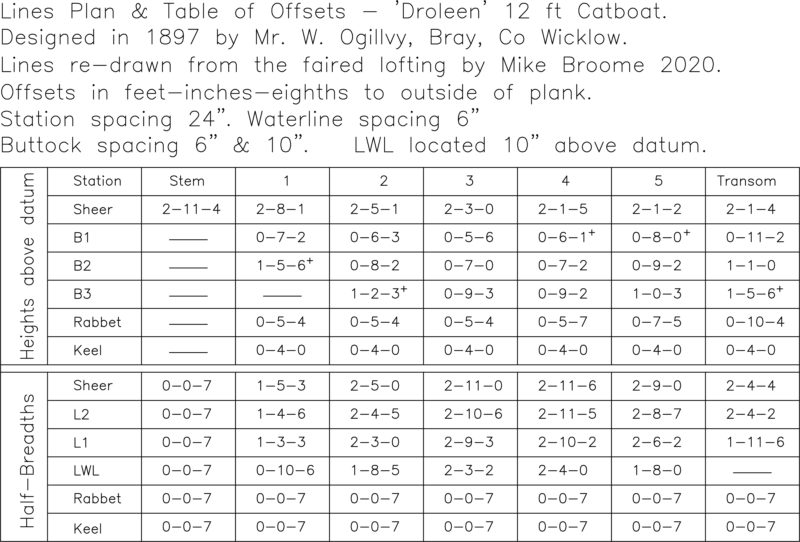

Before the lofting process began, BBA course tutor Mike Broome decided that there should be five molds instead of the three shown in the plans. This, and other anomalies in the plans, meant that the lofting process was more problematic than it might have been, but it allowed Mike to then produce a significantly more accurate lines plan and table of offsets.

The boat was built the right way up, and the construction process began with the dead-straight 1-1/2″ x 1-3/4″ sapele keel being laid on top of a temporary strongback. The triangular oak deadwood was fitted aft, and then the 1/2″ x 3-1/2″ sapele hog was laid on top of it and the keel, all glued with epoxy. The keel and the hog already had the centerboard slot cut into them. The 3/4″ oak transom was fitted along with its 1″-thick oak knee, while the laminated oak stem and apron—each 1-1/2″ thick and together forming the rabbet for the forward ends of the planks—were scarfed-in forward. The five temporary molds were then put in place.

The Droleen has 11 strakes of 5/16″ planking. The 6′ beam in the 12′ boat gives the hull a notably full shape.

The planking starts with the garboards. The plans called for 11 or 12 strakes, and it was considered that 11 would be enough, despite the extreme beam. Two strakes have full-length planks, but all the others have scarfed joints, some of them two. To cope with the bend and the twist, about 3′ of the forward ends of the bottom three planks had to be steamed. The planks are 5/16″-thick larch with 3/4″ laps between them. Once all the planks were fitted and fastened to each other with rivets, three struts were taken up from each sheer to the roof beams to allow the molds to be removed without the hull losing its shape. The inside of the hull was then primed.

Most of the steam-bent 9/16″ x 1/2″ oak ribs are continuous from sheer to sheer, but the two most forward are divided by the maststep, eight amidships by the centerboard case, and the aft two by the stern knee. After the ribs were bent in place, they were allowed to cool, then removed to be primed before they were riveted into place.

The internal fit-out began with the 13/16″ sapele floors, which also serve as sole bearers. The plans called for just four, all of them aft of the centerboard case, but it was decided to fit seven in all, partly for extra strength, but also to allow later fitting of sole boards over a greater area. Next came the 1-1/8″ x 3/4″ oak seat risers. It was initially thought that these would need steaming, but it was just possible to fit them without. The centerboard case—made of 5/8″ sapele with varnished oak trim—had previously been dry-fitted, and this was now fixed into place. The centerplate —3/16″ galvanized steel—was “originally a quadrant shape, meaning a large portion of it stuck up into the boat when raised,” said course tutor Mike. “I just tweaked the shape to a more conventional parallel-sided one to avoid this.”

Next came the 7/8″ x 1-5/8″ inwales, the 3/8″-thick caps, and the 3/4″ x 1-1/8″ rubbing strake, all in oak. The latter had to be steamed. The three 7/8″ oak thwarts were then fitted. The 8″-wide forward and middle thwarts gain some support from the centerboard case (the latter also with a knee fixed to the aft end of the case) and each of them also has two knees per side, while the 10″- wide aft thwart has a 5/8″ support, 3″ deep amidships tapering to 1-1/2″. The quarter knees are 1″ oak, while the breasthook, which doubles up as the mast gate, is 1-5/8″ thick. This is brought 17″ aft along the inside of the inwales—not as far as shown in the plans, but it was thought that they would become too thin to contribute any strength if they were brought farther aft. On top of the breasthook between the mast and the apron is a custom bronze fitting through which bronze pins are fitted to allow the mast to be lashed firmly into its gate.

The 7/8″-thick sapele blade pivots within a 2-7/8″-thick oak rudderstock. The tiller is also oak. The spruce spars are of hollow bird’s-mouth construction with oak cappings to seal the end-grain. The predominant feature of the unstayed cat-rigged sail plan is the length of the boom which, at 14′ 6″, is 2′ 6″ longer than the boat. It is thought that this was originally to allow a seaworthy low-aspect rig.

The aft end of the breasthook has a notch that serves as the mast partners. The mast is lashed in place with turns anchored by a pair of bronze belaying pins forward.

Stepping the mast is a simple enough job for one person by placing the heel into the maststep, pivoting it forward into the breasthook, and then lashing it there. The sail plan also shows a second sail which is referred to as a “jib/spinnaker,” but in truth it seems to be not really either. It is set with its tack on the end of a conventional spinnaker pole but is too small to be an effective spinnaker. Michael plans to make such a sail and pole at some time in the future, but for now the boat just has the single sail.

Although the Droleen in only 12′ long, it has plenty of room for a crew of four. The 112 sq ft sail has a boom that’s 14-1/2′ long, keeping the center of that sail area low.

I had the chance of a sail the Droleen on the BBA’s Launch Day when I climbed aboard from a RIB, swapping places with a couple of students. It was blowing a Force 3, with occasional Force 4 gusts; by the time the transfer was complete, the Droleen was in irons. Wishing she had a jib to back to turn the bow away from the wind, I put the tiller over the “wrong way” as we began to go backwards. I fully expected that when I then pulled the mainsheet in to fill the sail, she would just luff up again, but it immediately started sailing very easily. It then proved itself to be a very enjoyable and easy boat to sail on all points of sail, at all times well balanced and responsive. I had been a bit intimidated by the length of the boom and wondered how it would be to jibe. But I did so a couple of times with no issues at all, each time partly pulling the sheet in beforehand to give some control over the boom.

At one point the Droleen touched 5 knots in a gust on a close reach while the centerplate hummed satisfyingly. The massive beam gives the boat not only a great deal of internal space but also great stability. There were three of us on board—and there would have been plenty of room for two more—and while I steered from the stern seat to windward, my two shipmates sat each side of the centerboard case, sometimes on the center thwart, and sometimes on the sole where they were well clear of the boom. At one point when sailing to windward we had a bit of a gust and the leeward crewman instinctively began to move to windward. Before he could do so, however, the boat’s angle of heel stopped at about 10 degrees and he realized there was no need for him to move.

A pair of 9′ oars proved to be a good fit for the 70″ span between the oarlocks.

The Droleen also makes a nice rowing boat. Michael was concerned that the beam of the boat would make it difficult to row from the center thwart where the rowlocks are spaced 70″ apart and that it would be easier to use the forward thwart where they are 65″ apart, although he would need to make a raised seat to cover the centerboard’s handle, which lies across the thwart with the board up. As it happens, there was no difficulty rowing from the center thwart with the 9′ oars.

The Droleen is a versatile, well-behaved boat whose extreme beam gives plenty of space and stability, and it is great to see that the class is experiencing something of a revival after all these years.![]()

Nigel Sharp is a lifelong sailor and a freelance marine writer and photographer. He spent 35 years in managerial roles in the boatbuilding and repair industry, and has logged thousands of miles in boats big and small, from dinghies to schooners.

Droleen Particulars

[table]

Length/12′

Beam/6′

Draft, board up/6″

Draft, board down/32″

[/table]

The Droleen lines and offsets, drawn by BBA instructor Mike Broome, are provided here. For more information, email Mike at the Boat Building Academy.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Lovely boat. I am currently rebuilding a clinker sailing dinghy here in New Zealand that has the same length and beam. The design is a bit of a mystery but something may come to light in the future. Great to read that the sailing and stability aspects were favourable and also the rowing performance of such a beamy craft, bodes well for my boat.

Cheers,

Mike.

What a lovely little boat! It wasn’t just the boat that attracted me but the name of the design. Droleen, surely Irish for the little wren (The wren, the wren, the king of all birds…!), or in Irish, an Dreolín

I’ve spent the last few years rebuilding a 21′ wooden gaff cutter (re-launched 2019) which was originally built in the early ’80s by Liam Hegarty of Oldcourt boatyard.

And I need a little boarding boat….

How coincidental to find the first post by an O’Dwyer!

I am currently writing the history of the Bray Droleens. I am expecting it to be complete by the autumn of 2021.