In the early 1960s Martin Litton, a travel editor for Sunset magazine, came to the McKenzie River in Oregon to write a story. When he got there, he saw wooden drift boats on the water; they would change his profession, his life, and river running on the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon forever.

Martin and Pat Riley, his partner on trips in the 1950s, were planning to run the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon in 1962 before the Glen Canyon Dam opened the following year. They needed new boats because the cataract boats they had used on previous trips were at the bottom of the Colorado River. They had been patched so many times they were literally falling apart at the seams—so, midway through a descent through the Grand Canyon in ’59, Pat scuttled them at Pipe Creek and his group hiked out of the canyon on foot.

The fiberglass cataract boats Martin and Pat used on the Colorado then were built to a design first developed for plywood construction by Norm Nevils, a river-runner of the ’30s and ’40s, for running the cataracts—whitewater—of Utah’s San Juan River. They had a low profile with vertical sides and a slight rocker, and held only one or two passengers. They sliced through waves, rather than riding over them which was hard on the boats and made for a wet and often unstable ride.

As Martin watched the graceful McKenzie drift boats cutting through the technical rapids and surfing high on the waves, he thought he might have found the perfect boat for the Colorado. The boats sat with both ends rising almost a foot out of the water. With that amount of rocker, they could pivot and spin on the tops of the waves with just a flick of the wrist from the oarsman. The river flowed under and around the boats rather than colliding with the stern, pushing them relentlessly forward with the current.

Dave Mortenson Collection

Dave Mortenson CollectionDuring the 1962 trip Martin Litton rowed PORTOLA and Pat Reilly rowed SUSIE TOO, the new McKenzie-inspired boats. Brick Mortenson rowed FLAVELL II, a cataract boat .

Dave Mortenson Collection

Dave Mortenson CollectionDave Mortenson, ready for the river. The foam mix that his father Brick used to fill the space in his boat’s buoyancy compartments was very expensive so he used empty Clorox bottles to take up some of the volume. He sent Dave into every laundromat in the San Fernando Valley to dig through the trash looking for the plastic bottles: In those days they were the only plastic bottles you could find. If that wasn’t bad enough, Brick had Dave wear two bottles tied to his life jacket. Fortunately, the requirement for extra flotation was dropped. It had been, according to Dave, “a 13-year-old’s worst nightmare.”

Recognizing the advantages the boats would have on the Colorado, Martin ordered two from Keith Steele, the most active boatbuilder on the McKenzie. In the spring of ’62, Martin picked them up and commented on how big they were compared to the cataract boats. He and Pat initially referred to the new boats, PORTOLA and SUSIE TOO, as “monsters.”

On that Grand Canyon river trip in 1962 there was a third boat, FLAVELL II, a cataract boat built and rowed by Brick Mortenson who took his 13-year-old son Dave, with him on the trip. Almost 50 years later, I met Dave at the 2011 McKenzie River Wooden Boat Festival at the Eagle Rock Lodge in Vida, Oregon. He had come to see the boats that had first caught Martin’s eye and to talk with some local boatbuilders. Dave had a vision: He wanted to re-create that trip of ’62 on its 50th anniversary to honor his father and the other river runners who blazed the trail in these Oregon-built boats. When he brought up replicating those boats, I was hooked by the idea and his enthusiasm. I agreed to build a replica of PORTOLA, even though the only record of it was in old photographs and videos. A good friend of mine, Randy Dersham, agreed to build a SUSIE TOO. He had a boatshop on the McKenzie only a few miles from where the original boats were built. Dave would not succeed in having the replica FLAVELL II built until 2014 but he was thrilled that the two Oregon boats being built for the 50th anniversary trip.

Over the course of that summer, Randy, his son Sanderson, and I assembled the hulls of our replica boats. As we slowly bent the side panels around the frames, we heard the sickening pops of wood approaching its breaking point. We listened to the wood, slowed down our bending, held our breath, fastened the panels to the frames, and hoped they would hold. I wondered, with so much tension, would my boat just explode on contact if I hit a river boulder? We all felt better after we fastened the side panels to the frames and attached the bottoms, holding everything together.

With the hulls finished, I hauled mine to my garage shop where I could work at my usual snail’s pace. The hundreds of pictures and video from the 1962 and 1964 trips were my guide to building the interior.

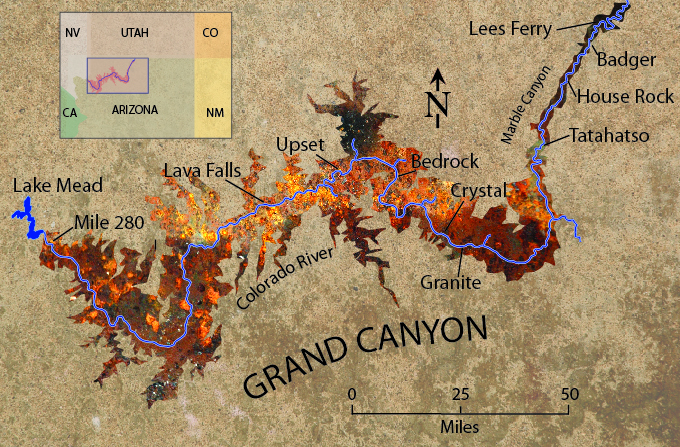

The paint on PORTOLA was still drying as I backed it out of the shop and headed for the Colorado River in the spring of 2012. Passing through Oregon snowstorms, Utah rainstorms, and high-desert dust storms, we finally reached our launching ramp at Lee’s Ferry, Arizona, 16 river miles below Glen Canyon Dam and the beginning of the Grand Canyon. Fifty years ago at this spot Martin Litton, Pat Reilley, Brick and young Dave Mortenson, and six other passengers launched three boats that had never touched water. I wondered whether they were either a bit crazy, poor time managers, or just very confident in their boatbuilding ability.

I eased my PORTOLA down the ramp for her first touch of water and prayed this would not be the most embarrassing launch in the history of Colorado river running. She slid off the trailer and floated for the first time in the quiet entry to the Grand Canyon. The crowd on shore was as pleased as we were to see PORTOLA and SUSIE TOO floating together alongside the cataract boat replicas FLAVELL, SUSIE R, and GEM.

In the clear pool above the Colorado’s first riffle, I took the first pulls on my 9′ red-and-white wooden oars and looked downriver, admiring the impressive rose-colored canyon walls rising 1,500′ on both sides of the river. The point of no return was only a few strokes away. Beyond it there would be no rowing back upriver against the current.

I was part of a 16-member team that included some of the most experienced oarsmen on the Colorado and five support rafts. I’d developed my skills in Oregon boats on Oregon water, but I was uneasy. This was the Colorado River, and I had only a fraction of an inch of plywood between me and disaster.

Dave Mortenson

Dave MortensonBadger is the first significant rapid on the Colorado downriver from the launch site at Lee’s Ferry. It has a 15’ drop and is rated Class 4 to 6 depending on the water level. The untethered oar Greg lost was fished out of the river down below by teammate Craig Wolfson.

Our first real test was a Class 5 rapid (a 1-to-10 scale is used on the Colorado instead of the I-to-VI classifications used elsewhere) called Badger just a few miles below Lee’s Ferry. It has a drop of 15′ over a sixth of a mile, an impressive wave-train of high rollers down the middle, and sharp hydraulics on the edges caused by hidden boulders washed into the river from two side canyons. At the start of the trip I’d been told I needed tethers for my oars, in case they popped out of the oarlocks and out of my hands. Pop out of an oarlock maybe, but out of my hands? Not likely! After logging thousands of hours and as many miles rowing a drift boat on technical water, I had never lost an oar, never even come close.

As I raced through the first drop, it felt like I was in the front seat of a roller-coaster and should stick both hands in the air and scream. A cold wave splashed over the bow and slapped me in the face. I dug the left oar deep in the current to get out of the wild ride in the middle. The river pulled back and lifted me out of my seat. In a split second of good judgment, I let go of the oar and avoided being catapulted out of the boat.

I suddenly had an untethered oar adrift in the water and only one in hand to finish the rapid. Craig Wolfson, one of our most seasoned Colorado river rats, was the safety spotter waiting in cataract replica SUSIE R in an eddy below the rapid. He fished my oar out of the river. “Welcome to the Colorado!” he laughed as he handed it over. That night I made tethers for my oars.

We camped where the Litton party camped and could recognize the places recorded in their diaries and photographs. Many nights I rolled out a canvas cowboy bedroll and slept on the soft sand under the stars wrapped in a wool blanket. When I had the energy to set it up, I slept in a canvas pyramid tent similar to those used in the ’60s. It had a familiar musty smell from the moisture of the morning dew that reminded me of the tents at Boy Scout camp when I was growing up.

Dave Mortenson

Dave MortensonGreg races PORTOLA down the tongue, hitting his line in Soap Rapid. This second major rapid has a 17′ drop and gave the rowers a feel for the river and their newly built boats.

About 40 miles downriver from Lee’s Ferry we camped at a place called Tatahatso, right in the heart of Marble Canyon where soft-pink stone walls rise up straight out of the river, leaving just a winding ribbon of river a half mile below the canyon rim. A narrow strip of sand nestled between the canyon wall and the river was the perfect campsite for our group.

Before dinner I took a hike in a side canyon above our camp with teammate Tom Pamperin, one of the support raft oarsmen. After a half hour of boulder jumping and trail scrambling we reached an overlook about 300’ directly above our campsite. In the fading sunlight the river looked like a thin twisted piece of chrome. We could clearly hear the clatter of pots and pans in the camp kitchen below, and the air had a wonderful aroma of campfire, tamarisk, and food cooking on the camp stoves. From this vantage point high above camp I began to see and feel the immensity of the canyon: I was amazed at how much bigger it was than I’d imagined.

We tried to replicate many of the 1962 photographs as we could. At Boulder Narrows a rock five stories high juts straight out of the river, forming a channel on each side of it. Perched on top of the rock is a helter-skelter pile of tree trunks and root wads and driftwood deposited by a high-water flood in 1957. They’re still there unmoved, a half-century later.

The camping gear used in the early ’60s was often canvas and wool. In a nod to that era, I camped every night using either a canvas tent or cowboy bedroll. Nighttime temperatures were usually in the ’40s. Here at Tanner Wash I pitched my tent away from the river and did a little hiking.

We talked around the campfires at night and over coffee in the morning about the rapids we had already run and the challenges of the rapids ahead. Each presents a different problem to solve and a unique challenge to overcome. At House Rock the main current sends you faster and faster toward a rock the size of a two-story house where the river makes a hard right turn. If you can’t break through the grip of the current and pull to the right, you’ll smash right into the rock and your boat will either flip, break apart, or get sucked into the huge hole on the other side of the rock. Hermit has a wave-train created by boulders buried underwater; it builds to a crescendo at a towering fifth wave followed by an exceptionally deep trough. At Bedrock the river runs with great speed into an imposing rock wall that violently splits the river in two. The safe line is to the right, but not too far or you’ll run through shallow water filled with boat-wrecking rocks. If you screw up and go through the left channel—and survive—you’re entitled to wear a T-shirt that says, simply, “I went left at Bedrock.”

Dave Mortenson

Dave MortensonRandy Dersham, rowing SUSIE TOO, hits his line perfectly between two explosion waves in Crystal Rapid. Before Glen Canyon Dam controlled river flows, Crystal was a minor rapid but a major flash flood dramatically changed its difficulty and is now considered by many to be the biggest rapid on the Colorado.

Crystal, a Class 9, is a loud, angry, and confusing rapid where waves explode out of nowhere and send boats spinning out of control. There never seems to be a clear line through Crystal, and there are two huge holes at the bottom on opposite sides of the river that can swallow a boat.

Dave Mortenson

Dave MortensonIn Lava Falls success and failure both take only take 30 seconds. Greg takes PORTOLA successfully through the maelstrom as safety kayakers stand by ready to come to the rescue.

And then there’s Lava Falls, a 10, with a steep drop at the top, big rolling waves, huge holes, boat-flipping lateral currents, and big rock obstacles. There is a scouting perch on top of a huge black boulder where you can watch the carnage of boats attempting the falls until you can make yourself believe there’s a way to run the rapid unscathed and muster up the courage to get back in your boat.

Dave Mortenson

Dave MortensonGranite, located at river mile 93 and rated a Class 8, requires a quick dip in the top hole in order to miss the larger hole at the bottom. Stefane Poirier, rowing SUSIE TOO, takes a big bite out of the hole but came popping out on one of the wildest runs of the trip.

Granite is a Class 9 that you can hear long before you can see it. Its roar is louder and more unsettling than most because of a precipitous drop and haunting echoes from a sheer canyon wall that rises straight up on the far shore. You can pull off the river and walk several hundred yards down to the point where the water drops out of sight. The only path is on the far right, balancing boats on a ridge of water welling up between the canyon wall on one side and one of the largest and deepest holes on the river—a Scylla and Charybdis with no margin for error.

There are rapids to run in almost every mile of the river, though most are rated no higher than Class 6. At mile 150 we arrived at Upset Rapid, one of the prettiest and yet most treacherous rapids in The Grand Canyon. With a beautiful red canyon wall as a backdrop on one side and a cobble garden of boulders on the other, it’s possible to scramble the entire length of this rapid on the river-right side at the water’s edge. It’s hair-raising to be so close to the power of a Class 8 rapid as it thunders along between the walls and over the ledges from top to bottom. One ledge at Upset runs across the entire width of the river, creating a steep drop that can easily flip boats. There is a deep hole on the right, and the run along the left requires nerve and a steady hand from the boatman to put the nose of the craft as close to the left wall as possible.

As we picked the running order for this rapid, we sent a few of our support rafts to test the line before sending the wooden boats. Tom was the first to go. He set up his raft for a river-left run at the top of the rapid and dropped into the turbulence. With his strong and steady rowing he avoided the dangers of river right, hit the ledge hole nose-first, and powered through the drop. At the bottom of the rapid he eddied out and stood by as a safety boat.

Yoshi Kobayashi went next. At just 4′10″ she has to stand up to power the oars and move the big raft through the rapids. Just before the ledge the river turned her, and she hit the drop-off slightly sideways. The raft boat hit the dip and stopped abruptly, and Yoshi was thrown into the fast-moving cold water. She managed to swim to the raft and grab the flip lines on the upriver side but was unable to pull herself up onto the raft. Craig, this time rowing SUSIE R, another cataract boat, tossed a throw-rope and pulled her out of the icy water.

Dave Mortenson

Dave MortensonUpset Rapid at mile 150 has a 15’ drop and a big spread in its rating: Class 3 to 8 depending on the water level. Greg keeps PORTOLA perilously close to the canyon wall in order to break through a big lateral wave at the bottom of the run.

I was next. PORTOLA dropped into and flew down the rapid so close to the canyon wall that I thought she’d leave red paint on the rocks. I hit the ledge bow-first and dropped over. I pushed hard to get enough momentum on the climb out of the trough; then a tidal wave of water crashed over the bow and over my head, and PORTOLA rose as if shot from a cannon. The bow pointed straight up into blue sky, and I thought PORTOLA might pitchpole backwards. Breaking through the crest of the wave, I struggled to see through the sheet of water pouring over my face. PORTOLA landed hard, but with a few tugs on the oars I was safe in the eddy at the bottom of the rapids. This was what it had been like to be in this exact spot a half century ago, exhausted and elated in a gentle eddy at the bottom of a powerful and inspiring Colorado River rapid.

We had replicated many elements of the 1962 trip—the boats, the campsites, the pictures—but during our three weeks and 280 miles on the river the excitement of running each rapid, the dread as we heard another rapid ahead, the emotional highs and lows we shared with teammates, and the awe that the Grand Canyon inspires were experiences uniquely our own.![]()

Greg Hatten is an outdoor writer, a consultant for active-consumer products, and a licensed Oregon Outfitter and Guide who hosts outdoor river adventures in a hand-crafted wooden drift boat pursuing steelhead on the fly.

Dave Mortenson

Dave MortensonA dam was almost built near here but Martin Litton and his fellow river runners documented their travels through this amazing place in 1962 and again in 1964 and showed the world what would be lost. Greg and Pam Mortenson in the replica PORTOLA are surrounded here by the vertical Redwall limestone cliffs that were saved, in part, by the original PORTOLA.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your travels in a small wooden boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Join The Conversation

We welcome your comments about this article. If you’d like to include a photo or a video with your comment, please email the file or link.