I arrived at the top of the boat ramp at Riffe Lake around 6 p.m., on a cool evening in the second week of March. I had some daylight left, enough to get the boat in the water and row the mile and a quarter to the north side of the reservoir where I would drop anchor for the night. I piled gear, groceries, and water jugs into the cockpit without keeping track of what I put aboard or where it went. I only knew that there was nothing left in the car and whatever I’d brought was aboard. I’d sort it out later.

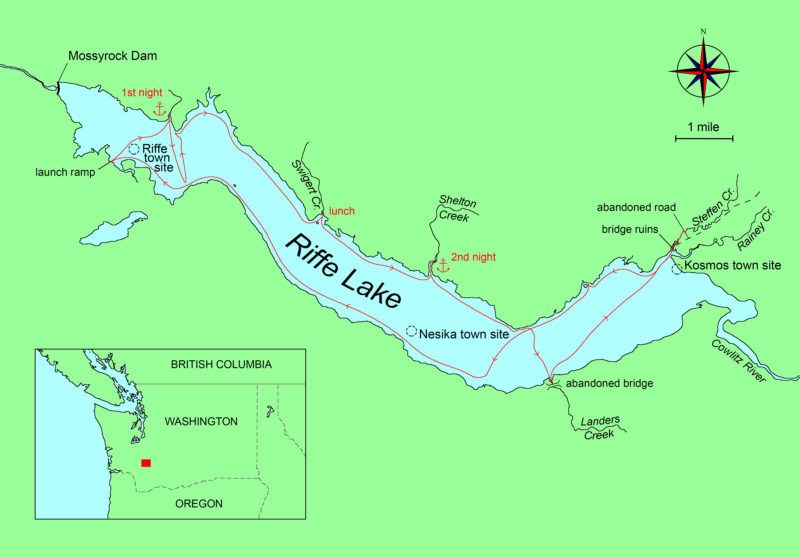

Riffe Lake is a reservoir a dozen miles long from Mossyrock Dam to the mouth of the Cowlitz River; 14 miles if measured on a map down its center, along the long sagging curve of its east end and across a jog at the west end that looks like a displaced fracture. The reservoir was down about 25′, and between the water and the forested hills surrounding it, there was a broad band of buckskin-brown dirt as far as I could see. Backing the trailer down the 150-yard-long ramp across that barren landscape was like descending into a flooded open-pit mine. Of the five hinged sections of floating dock at the bottom of the ramp, only the last one was afloat. I eased HESPERIA, my 16′ cruising garvey, off the trailer into the water and pulled the bow up on the beach.

After I parked the rig, I shoved off and moved bags out of the way so I could sit down to row. I could feel the weight of the gear as HESPERIA slowly gained momentum. The water, food, firewood, gas, motor, spars, and sails all had to be set in motion, but after a dozen strokes they helped carry HESPERIA forward. The air was still, the lake quiet, and the cockpit resonated with the sound of water purling around the hull.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorWater levels on Riffe Lake vary seasonally with the winter snowpack feeding the reservoir. It was 25′ below capacity during my cruise.

Just 100 yards from the ramp, I had rowed from the shadow of the land into sunlight and the moisture-laden air blanketing the water glowed the color of straw. The dam, 1-1/2 miles to the northwest, was in shadow—just a dim sooty line at the water’s end—while the north shore was radiant in the brassy light of the evening sun.

Somewhere in the water below HESPERIA, 200′ down, was what remained of the town of Riffe: the concrete foundations of a general store, a post office, two Baptist churches, a gristmill, and the homes of 350 souls. The Port City of Tacoma, 50 miles to the north, needed electricity, and wanted it cheaper than the power purchased from a power plant on the Columbia River, so the city appropriated the valley around the Cowlitz River under eminent domain and began building the Mossyrock Dam in 1965. Surveyors plotted a contour line through the forests where the reservoir’s water level would be when the dam was put into operation. Everything below that line was logged or demolished.

Nearly 2,000 people were forced to leave before their homes were torn from their foundations.The dam rose 365′ above the riverbed when it was finished, and it took eight months for the reservoir to fill, swallowing up not just Riffe, but also Nesika, a town 6 miles upstream, and most of Kosmos at the east end of the reservoir.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

Just as I drew near the north shore, the sun impaled itself on the tips of ridge-top trees, and split in three behind a picket of slender tree trunks. The light that had been spilling over the ridge angled upward, and the hills to the east grew wan in the pale purple penumbra.

I reached the mouth of the creek where I planned to spend the night, a deep nick in the shoreline, 200 yards long and 100 yards wide at its mouth. At the top of the band of bare ground around it were scattered tree stumps, sawn straight through at the top, with roots exposed when the reservoir’s high water washed away the soil.

Halfway into the creek, I lowered the anchor, paid out the chain and the soft braided rode, and when I came to its end, I was still holding the full weight of the anchor and chain. I had not given the stream its due—it had cut a ravine that was beyond the 100’ reach of my rode.

Sitting on the foredeck with my heels skimming the water, I paddled farther into the inlet and tried again. I felt the rode go slack with 50′ of rode in the water. I let HESPERIA drift downstream, nudged by a chilling north wind. Like a fisherman sensing a fish nibble at his lure, I felt the anchor flukes tripping over rocks. When they caught and held, the rode pulled tight.

I started working through the clutter onboard to prepare for the night. Before I could raise the roof on the pop-top cabin, I had to get the weight of the spars and sails off. I stepped the main and mizzen masts and set the bag holding the rest of the spars across the cockpit. Inside the cabin, I put the floorboards on the side-bench ledges, laid on my back, and, with my feet centered on the cabin roof overhead, pressed the roof up.

The wood stove didn’t require much time or wood to warm and illuminate the cabin. The portable loo is stowed in a locker in the cockpit, but it was too cold outside to use it there.

With the stovepipe connected to the woodstove and chimney cap on, I was ready to make a fire and warm the cabin. The wind made a low whistle and created enough draft to pull my lighter’s flame into the firebox to ignite the crumpled newsprint and kindling. With the fire going and the flames glowing bright orange in the mica window, I set a pot of soup on the stovetop. I was feeling a bit grubby after the long haul of getting to the lake, so I set the water jug on the roof of the cabin and connected it to the fitting that feeds the cabin’s plumbing, including the heat exchanger next to the stove. While the soup was heating, I filled the sink with warm water, shaved, and washed my hands and face.

After dinner I stepped out into the cockpit. The night sky was full of stars. I set the cockpit floorboards on the cabin roof to make a platform where I could lie down and wrap myself in a wool army blanket to look up at the patch of sky above the creek. Cassiopeia’s W, the Big and Little Dipper, and Orion with his three-star belt were all out. I counted six of the seven Pleiades; Jupiter was bright enough to paint a thin line of its reflection on the lake. A satellite drifted across the Big Dipper and blinked out.

I made the bed with the cabin floorboards filling in the space between the side benches, and cushions covering the queen-size platform. With clean sheets, my pillow from home, and two sleeping bags spread out as comforters, I settled in to sleep, but the wind strengthened and even in the lee of the woods surrounding the creek mouth, it was strong enough to stir the water. The constant slapping of wavelets against the hull was keeping me awake. Out on the lake, in the 2-mile fetch from the dam, a northwesterly was kicking up waves large enough to wrap around the corner and work their way up the creek. They rocked the boat and the mainmast was knocking against its partner.

Getting up in the middle of a cold night to move the boat farther inland was a bit of a nuisance, but it was worth getting a look at the lake by moonlight.

It was no use trying to sleep, so I got dressed and stepped outside into the cockpit. I unstepped the mainmast and set it on the cabin roof, then lay belly-down on the foredeck to pull the anchor up. I piled the dripping rode to the side so the water would run off the deck away from me. When the anchor broke free, the bow fell away quickly, so I promptly hauled the rode and chain in, grabbed the paddle, and pulled the bow back into the wind. As I paddled HESPERIA farther into the creek, the light of the newly gibbous moon lit the way ahead. I made slow but steady progress and the water remained deep beneath the hull even as the banks, clearly visible but colorless in the moonlight, closed in on HESPERIA. The bank to starboard was steep; to port was a gentler slope of short grass and tall crumpled reeds. I stepped ashore, taking the anchor with me and pushed the flukes into the firm mud. I pressed a stick into the mud at the water’s edge to see if the water level would change during the night, a habit I developed from cruising tidal coastal waters and from rivers where rain and dam releases can quickly change the water.

Back aboard, I paid out the rode and let the wind draw HESPERIA into deeper water. Now in quiet water, I settled back into bed, and tucked my hands and feet in close to warm up. The cabin was cold but HESPERIA was quiet, and I was soon asleep.

At dawn, the starboard cabin windows framed a lacework of leafless trees against a pale sky. I sat up in bed and pulled a handful of kindling from the locker beneath the stove. The Western red and Alaska yellow cedar start a fire quickly and impart their fragrance to my bedding, which I stow in the same compartment a bit farther aft. As the fire took hold and the stove radiated light and heat, I lay down in bed again and drew the covers over myself. In about ten minutes I raised a bare arm and felt the hot air pooled against the ceiling. I sat up into the heat and waved a hat around to stir the air and spread the warmth throughout the cabin. Up and dressed, I breakfasted: a fluffy smoked-salmon omelet, egg whites whisked stiff, yolks and crumbled salmon folded in, and cooked in a pan on the woodstove. I then let the fire die down, and put my shoes and coat on for a walk.

Downstream from HESPERIA, the trees at the creek’s mouth surrounded the view of lake with a tattered fringe of overlapping bare branches. One tree was suspended nearly horizontally above the bank, and others leaned over it as if pushed by the crowd of trees behind them. Whitecaps were skimming across the lake, but the wind in the creek’s slender ria was reduced to a sigh.

In the morning, I took a short walk into the woods around the unnamed creek.

I stepped ashore near the stick that I’d put at the water’s edge during the night. It was now 12″ from the water, so the level of the lake had dropped just a couple of inches. It was no cause for concern and likely just a wind-driven seiche dragging the water to the far end of the lake. There were deer tracks in the mud, one of them pressed into a bootprint I’d made during the night.

I stepped over the creek and climbed the slope on the east side of the ravine. High up on the bank, a pair of fluted stumps tilted downslope, their bare roots fanned out, touching lightly on the soil. One stump bore two notches, each a handspan wide, cut by the logger who had felled the tree. With steel-tipped springboards jabbed into the notches, he could stand higher and cut the tree where the trunk is narrower down above the flare to the roots. Even then, the stump was a good 7′ across where it had been sawn through.

I’d brought my axe and with two swings, cut a flake of wood from the side of the stump. Beneath the dull gray surface, the wood was a rich brown color and its sweet fragrance was clearly that of Western red cedar. The other stump had two deep saw cuts on the water side of the stump, just below the cut that had brought the tree down. Such wasted effort would only have been tolerable for loggers working with chainsaws instead of handsaws.

The pale fuzz on a stinging nettle is made up of hollow glass-like needles that break at the touch and inject formic acid and other compounds into your skin. Heat makes the needles harmless and breaks down the acid. Cooked young nettles are delicious.

In the woods at the top of the rise, there was level ground covered with moss and arched over by saplings that I had to step over and stoop under. I picked my way inland a few dozen yards and saw a patch of black no bigger than a bathmat. It was asphalt, the only indication that under the carpet of moss and scrub there was a paved road. If it continued on its line south, it would have dropped into the lake. The asphalt was also concealed by a patch of shin-high stinging nettles. I didn’t have any gloves with me to pick them so I returned to the boat and collected some of the plastic bags my groceries were in and returned to the nettles to harvest them with the bags on my hands.

In the morning, I lowered the cabin top and raised the sails, expecting to spend the day sailing.

Back at the boat, I put my dry suit on, stepped the mainmast, lowered the cabin roof, and rowed out toward the lake. A brisk easterly, funneled by the chain of hills to the north and a 1,000′ high ridge to the south, was churning a few whitecaps in the middle of the lake.

I began sailing from the cockpit, steering with the line running through the cabin and the perimeter of the inwales and attached to the tiller. Even with the heaviest cargo in the cabin keeping the bow high, the biggest waves slapped the bow and sent spray into the cockpit. I crawled over the cabin roof, removed the hatch at the back, and dropped in to stand on the cabin floorboards. I was out of the spray, and with the hatch coaming at my waist, I was only half exposed to the wind.

I came about as I neared Riffe Lake’s south shore and, as HESPERIA settled in on the starboard tack, it was clear I wasn’t going to get far beating into the chop. I bore away and sailed back toward the cove I’d anchored in. When I reached the lee of the creek mouth, I crawled forward to strike the whole rig, main first, then mizzen.

I had set out without the motor in place. It was stowed in HESPERIA’s tiny aft cockpit, the 20″ space between the transom and the cabin. I got the motor clamped in the notch in the transom, fired it up with two pulls of the starter cord, and motored along the north edge of the lake, skirting the shore to take advantage of the small lees there.

The stumps along the shore haven’t moved an inch from where the loggers left them a half century ago, but I couldn’t help but see them as living things in flight. Many, like this one, anchored to a rocky slope with its profusion of limbs, reminded me of Marcel Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase.”

Stumps were scattered everywhere on the slope between the lake and the forest, some elevated by their roots above the rust-colored soil, others clinging to steep-faced rock outcroppings, all leaning toward the water, an odd migration of spindly-legged creatures down the slope of the shore. It was hard not to think of them as once-mobile creatures, caught on the wrong side of the surveyors’ line during the antediluvian slaughter of the forest. It looked as if the stumps, decapitated and stripped bare, had risen in a blind downhill rush on thready amoebic limbs, only to be stopped dead a few strides into their descent of the valley.

Just a short distance and two turns from the lake, Swigert Creek’s inlet made a nice stop for lunch, but the two waterfalls (one here at the bottom, hidden by driftwood, and the other around to the right) would have been too noisy for an overnight stay.

On its way to the lake, Swigert Creek spills over boulders and under and around stumps and branches.

The wind eased as I approached a bay with a steep-sided rocky opening in its northwest corner. I killed the motor with the line tied to the motor’s deadman switch, crawled aft from the cockpit, and kicked the outboard up. I rowed the dogleg into the passage and, about 175 yards in, it ended in twin creeks cascading over boulders cradled in steep-sided ravines. A toppled tree trunk, 60′ long, spanned the mouth of one of the creeks and served as my dock. Its bare wood was silvery and smooth to the touch. I tied the painter to the blunt broken end of one of its roots and, in the still air of the gully, settled in the cockpit to make lunch.

Stewed just until they are soft, stinging nettles are delicious.

With the butane stove fired up in the cockpit, I cooked the nettles in a pot with a cup of water. The leaves, like fresh spinach, wilted and turned a darker green, and as soon as they were soft I could eat them without getting stung. They had a mild bite of pepper and a rich buttery flavor like artichoke hearts. When I finished them, I sipped the emerald green broth they’d cooked in; it was as flavorful as the nettles. I finished lunch with some vegetable soup from my favorite deli. It was not nearly as good as the nettles.

Separated from the lake by two sharp bends and sheltered from the wind in any direction by the forest, Shelton Creek’s ravine was as quiet an anchorage as I’ve ever had.

I motored another 2 miles east along the shore and turned north into a broad, 150-yard opening and then a blind corner 400 yards in. Steep, bare rock walls rose on the west side; to the east the shore was sloped and sandy, inhabited by stumps. The inlet veered to the right then immediately made a sharp turn to the left. Another third of a mile in, the passage came to an end. There, a creek had cut its way down through the forest floor, leaving moss and ferns hanging over the lip of eroded soil 20′ up, and the water wandering around logs and boulders in its bed.

When I reached the end of the inlet, I considered anchoring, but worried that there might be anchor-snagging driftwood on the bottom. Shelton Creek enters the inlet at the snag sticking out of the water at the left.

The banks of the inlet were too steep for exploring the woods, so I didn’t try going ashore. Rather than drop the anchor, I tied a line across the inlet, from one stump at the waterline on one side to another on the opposite bank. It took the anchor rode, the mainsheet, and another length of line to span the water. I snugged the line tight with a trucker’s hitch on one end, then tied HESPERIA’s painter to the middle.

To keep HESPERIA from wandering around during the night, I stretched a long line across the inlet and tied her bow and stern to it. I could sleep soundly without having to get up to see if that boat was still in a safe place.

With the cabin readied for the evening, I made French fries (russet potatoes, pan-fried in butter) as an appetizer and then cooked a dinner of sautéed broccoli and yellow bell pepper, with quinoa and chicken breast on a bed of tortilla chips topped with salsa.

It was still early in the evening, so after dinner I readied a bath. I took the rugs out—they needed a shake anyway—and snapped the tub in. I made it from the same tough coated material I used for the hull of FAERIE, HESPERIA’s folding coracle tender. The tub’s corners have snaps to hold them up to the ledges of the cabin benches. During dinner, I’d had a pot of water warming on the stove and it was quite hot, so I mixed it with cold water to cool it down to about 110 degrees. I poured the water into a gallon plastic jug with a knife slit in the lid for a shower head. After my bath, I folded the tub, with the water in it, and emptied it over the side of the cockpit. I air-dried sitting next to the stove in the cabin’s sauna-like heat.

High clouds had slipped in from the south during the evening, and in the dark it began to rain. I got the sleeping platform arranged and stepped into the cockpit for one last look-around. The anchorage was very well protected, and the only wind was the flow of cold air from the hilltops following the creek, just enough to tilt the column of gray smoke rising from the chimney into a starless ebony sky.

When I laid down to sleep, the inlet was so still that HESPERIA could have been aground. With the lights out, the cabin was lit by the agate glow from the last embers of the fire. The rain intensified and then stopped, leaving only the hushed voice of the creek slipping around its bed of boulders.

In the morning I sat up, filled the stove with kindling and scraps from my shop—bits of wood that I recognized from several of my projects. I lay back down, covered up, and waited for the cabin to warm and for the condensation on the windows and ceiling to evaporate. As I got dressed, the rain was so light that I could no longer hear it on the cabin roof, but I could see its scintillas in the dark reflection of the woods’ shoreline shadows.

To occupy the cockpit without getting wet I needed to get the canopy up. I set up the frame, which looks like a boom gallows but set in the wrong end of the boat, and snapped the canopy to the cabin roof and the gallows. I made a comfortable seat with the throw cushion, did a little morning reading, then put FAERIE together and slipped her, tethered, over the side. I set the cockpit table for breakfast; soup warmed on the butane stove, crackers, and blueberries.

Most of the shoreline was too steep to climb, so I paddled FAERIE, my folding coracle tender, for my morning constitutional.

I stepped aboard FAERIE and paddled around the inlet, first to the creek, where the bottom was littered with waterlogged driftwood, and then out to the bend in the inlet where gray-barked deciduous trees perched on the banks were flocked a bright electric green with lichen. I happened to have my GPS in my PFD pocket, so I turned it on and checked FAERIE’s top speed: 2.1 knots. She couldn’t even keep ahead of her own wake.

It had stopped raining by the time I returned to HESPERIA. I made ready to get underway, gathered up the shore lines, topped up the outboard’s fuel tank, and motored slowly out of the inlet.

All around the lake was a band of ground that was bare except for the stumps of trees logged in advance of the reservoir’s filling.

This knoll was once an island, but the low water has tied it to the mainland. There is a clearing in the middle of the knot of trees that would have made a nice place to camp but for all the branches strewn over it. During a strong wind, it would be a dangerous place to be.

The bridge over Landers Creek is cut off from the roadway it once served. The concrete-paved bridge deck, even though it is isolated from the land, has begun to sprout grass and saplings.

On the south side of the lake I could make out a pale-green stripe, which turned out to be a bridge when I took a look with the binoculars. As I got closer, it was clear that the bridge wasn’t connected to a road on either side. The lone disconnected span was held up by two concrete hammerhead piers and straddled a creek, looking like a giant dinner table.

Landers Creek has created a sandy delta that is one of the few level beaches on the lake.

With HESPERIA pulled up on the sand at the creek’s mouth, I scrambled up a bank of loose rocks to the east end of the bridge where the road leading to it had sloughed away, leaving a 20’ gap. The road bed was covered with grass, making it a pleasant, if narrow, meadow, and 100 yards to the east it was blocked by a wall of brush. I didn’t try crossing the creek to see the road on the other side. When it was passable, it must have taken traffic 3 miles to the west to Nesika, now at the bottom of the lake.

The roadway to the east of the bridge has turned into a meadow that is slowly becoming part of the forest again.

A breeze out of the west promised good downwind sailing to the far end of the lake, so I stepped the mainmast, broke out the square sail, and readied the halyard, haul-down, and sheets. I motored away from shore, killed the outboard and cocked it up, then lowered the centerboard, and raised the square sail. Spread by its upper and lower yards, it filled instantly and HESPERIA surged forward. I’d led the sheets through a block on the forward end of the cabin roof, so I scrambled through the cabin, a tight fit with the roof down, and stood up in the hatchway to take the helm.

The square sail means bringing two more spars and the sail but it’s my preferred rig for runs with a bit of a broad reaching. My 14′ push pole doubles as a selfie stick.

With one hand on the tiller and the other holding both sheets like the reins of a horse, I set a course northeast, across the lake and across the wind. With the board down, and the sail angled to face the wind, HESPERIA did well on a broad reach, making 3.5 knots. Water boiled up from under the transom; the lower yard was bent by the pull of the clews on its ends. In the middle of the lake where the wind was stronger, the GPS showed a steady 4 knots and flickered as high as 4.7 knots.

With the square sail pulling well, HESPERIA leaves a gurgling wake the equal of that created by the outboard.

As the end of the lake drew near, I peered forward by bending down to look across the cabin roof and through the space between the foot of the sail and the lower yard. Ahead, at the edge of a low brushy plain that had once been part of Kosmos, there was an inlet leading to two winding creeks.

This brush-covered flat plain just above the lake level is a small part of the Kosmos townsite. The rest of it is underwater.

Steffen Creek, the one to the north, would allow me to continue sailing downwind, although through a few twists and turns. The other, Rainey Creek, took a sharp 90-degree turn across the wind, and the square sail, not well suited to a close reach, would have to come down. My plan was to sail the northern creek until I was far enough inland to be out of the wind’s reach.

From upwind, this concrete “deadhead” was practically invisible, just a small whitecap that occurred more than once in the same place. The slightly brighter diagonal in the water is the glow of a horizontal piece of a demolished bridge.

Right at the entrance to the north creek I saw a small section of a wave trip over a deadhead that was just below the surface. As I sailed past with it on the port side, I got a better look at it. It was concrete, a tilted post rising above a jumble of pale pieces barely visible in the ruffled water. To starboard, a larger structure of concrete rose a few feet above the creek’s surface at an awkward angle, and on the shore beyond it was a section of a paved road with a faded white dashed centerline that started at the gravel at the water’s edge and ended in a stand of grass 50 yards away. I had passed over the ruins of a bridge, one of the remnants of Kosmos.

This short section of road used to carry cars and trucks to a concrete bridge spanning Steffen Creek. In 1968, the Army Corps of Engineers used the bridge as a training exercise, first testing a variety of explosives to see what damage they could do, then blowing up the whole bridge and leaving the rubble behind. A few of the remains rise above the creek’s waters.

The initial plan for the Mossyrock Dam would have spared Kosmos and left it safely above the reservoir, but a year before construction began, a proposal to make the dam 20’ higher was approved. That doomed Kosmos, and as at Riffe and Nesika, all of its buildings were torn from their foundations. A checkerboard of concrete slabs, a handful of roads that go nowhere, and the ruins of five bridges on a plain a few feet above the lake remain visible; the rest of the townsite is under water. A quarter mile and three bends farther up the stream, the trestles of a railroad bridge face each other from opposite banks, with nothing spanning the 100′ gap between them.

The railroad that led to Kosmos is gone, its rails pulled up and sold for scrap. The trestles on the banks of Steffen Creek are the most notable of its few remnants.

I hadn’t anticipated that the wind would blow unabated well into the creek. I brought the square sail’s starboard leech into the wind to slow HESPERIA’s rush into the narrowing creek.

The wind hadn’t let up as I had thought it would, and HESPERIA made quick progress over the next 200 yards toward a bend that I couldn’t see around. I started my turn, clipping the grass at the apex of what turned out to be a U-turn, and realized that the only thing I could do was aim for the grass on the other side of the bend to bring the boat to a stop. I almost made it, but a bit of wind caught the top of the square sail and nudged the bow to port, and the last of the momentum carried HESPERIA into a 6′-tall vertical bank that was a conglomerate of hardened dirt and bowling-ball-size rocks. The whole boat shuddered when the port corner of the bow made contact. I rushed forward, grabbed the paddle, and pulled the boat into the grass where I could park and drop the sail. The damage wasn’t bad. I could fix it when I got home.

I had to give up sailing the creek when I wasn’t able to round this bend, and instead of bringing HESPERIA to rest in the grass at the right, I hammered the bow into a stone-filled earthen wall.

I carried on under power, but I was able to motor only another 200 yards farther around a broad bend to find the shoaling creek bed was blocked with brush. There wasn’t enough room to turn around, so I cut the engine, turned to starboard, and plowed to a stop in the grass. After I paddled the stern around, I started the engine and headed back out to the lake.

Steffen Creek’s “navigable” section came to an end in grassy shallows a little over 1/2 mile in.

Leaving Steffen Creek, I headed back out into the lake to make my way to the launch ramp. The cloud ceiling had lowered over the ridge looming over the south shore.

Once I was back on open water, it was time to head home. To make the long run to the launch ramp, I dropped the rig and raised the cabin top so I could motor west in comfort. With the hatch cover in place and the doors closed, I was warm enough just being out of the wind. Seated comfortably on cushions in the warmth of the cabin, I could steer with just a light touch on the tiller line. The top of the ridge above the lake’s southern shore was lost in a low, gauzy layer of clouds. The miles of shoreline slipped by, and at some point, without knowing exactly where, I passed over Nesika. The town took its name from Chinook jargon, the trade language spoken in the Pacific Northwest in the 19th century. Nesika is the word for us.

Concerns about the ability of the Mossyrock Dam to survive an earthquake intact have led to keeping the water level well below its designed capacity, so the waters of Lake Riffe will never rise again to meet the edge of the living forest. But there are already areas of the shoreline where grasses, brush, and saplings have taken root and the green of the hillsides will eventually reach down to the blue of the water. The ancient stumps will be embraced by a new forest, all of the old abandoned roads will be covered by moss, and no trace of Riffe, Kosmos, and Nesika—us—will remain.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Magazine. This story includes photographs and descriptions from a subsequent day trip to the lake. A previous adventure with HESPERIA and FAERIE, along with videos and more information about the boats appears in “A San Juan Islands Solo” in the June 2015 issue.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Absolutely wonderful adventure. Well done. Do you have a link to where one could get plans to start building one of our own? Wife took one look at the article and said , “I want one!” Thanks.

Thanks for the kind words. Unfortunately I didn’t draw up any plans for HESPERIA. The design was conceived as a cross between a Caledonia yawl and an Escargot canal boat. I made a number of sketches to come up with the cabin and sailing rig, then started with the Aphasia hull by Phil Thiel, enlarged by 10 percent (if I recall correctly). With the hull complete, I mocked up the benches, decks, and cabin with sticks and cardboard, making sketches to do the math for finished dimensions as needed. I was just hoping my ideas worked out—they did, fortunately—and wasn’t thinking about a market for the plans.

I totally second that thought! What a beautiful ship. I want one too! Great Job!

Great story. I have read an earlier adventure of HESPERIA; very interesting camp cruiser.

DJ

Beautiful little boat, Chris!

What are her dimensions?

Thanks, Ken. HESPERIA is 17′ long and has a beam of 6′ and a depth amidships of 25-3/4″.You can find the story of her origins and videos of her in action in a previous story I wrote for the June 2015 issue, “A San Juan Islands Solo.”

Wonderful article, Chris, very evocative. Can you provide some more information on that neat little wood stove?

Thanks, Pete. The wood stove is the second of three that I’ve made. The first was for the Escargot that my son built. The design called for a storage locker in the 24”-wide space between the main cabin aft and the sleeping quarters in the bow. I looked for quite a while to find a stove that would fit, and while there were some small stoves designed for “hot-tenting,” they were rather expensive. I had inherited an oxy-acetylene torch kit from a good friend, but I hadn’t done much welding, so my first effort was a bit ragged. The steel is about 1/16” thick (I don’t know the gauge) and came from a piece about 4’ x 5’ that was used by an office mate for the mat for a rolling chair at her desk.

I use a jig saw with a metal-cutting blade to cut the pieces I need, then bend them with a sheet-metal brake I made. I tack-weld the seams with the torch before applying a weld on the full length of the seams. That first stove was rectangular and pretty straightforward. It didn’t have enough draft because I’d made the air intake with a bunch of ¼” holes. After I modified that to increase air flow, it was fine.

HESPERIA’s stove was made to fit in a corner and face diagonally into the cabin. I just drew the shape I wanted and went from there. All of the stoves have windows of mica that I ordered online. They make a world of difference. I can see the state of the fire inside without opening the stove and the windows illuminate the cabin. Even through the windows are small, they invite the same relaxing gaze that campfires do.

Because the stoves are in tight spaces, I protect the surfaces around them with metal shields. Home Depot has some stamped steel grills that look good and block a lot of the heat. The Escargot has a guard of corrugated steel.

HESPERIA’s stove is the only one with a heat exchanger. It’s a maze of ½” copper pipe with a couple of 1” reservoirs to increase the volume of heated water. The plumbing for the exchanger crosses the cabin to the sink in the opposite corner to provide hot running water.

The stoves have 2” pipe for air intakes. A bar across the middle of the opening in the inside end of the pipe is threaded for a ¼” x 20 screw that has a circular plate to regulate the flow of air into the stove. There’s no need for a damper at the stovepipe.

I painted the stoves with flat black paint formulated for barbecues and light a fire to outgas the paint before installing the stove in the boat.

I’ve been quite spoiled by the cozy heat the stoves provide.

A cruise well done in the spirit of L. Francis H.

– bk

What a great way to start my day. Sipping coffee and reading your story about a great trip on a wonderful boat.

I have seen a number of small boats with aft cabins like yours. I love the look but what is the practical advantage/disadvantage of this type of arrangement? Is it to keep the cabin in the high volume portion of the hull?

Having the cabin aft does indeed keep the take advantage of the greater hull volume aft. The width at the transom offers more space for the head of the sleeping platform in the cabin. The greatest width is amidships, of course, but the wood stove and the sink are there. I still a good amount of space between them and my feet can fit under both when I’m in bed. A few other benefits: for motoring, the cabin isolates the cabin from the noise of the outboard; I can see over the cabin top when it is lowered, but the view forward is better without the cabin in the way; access to the main mast is much easier.

Nice trip and a GREAT write-up.

Partially-drained hydro reservoirs are not usually top of mind as cruising destinations, but your excellent little cruise proves that there is interest and adventure to be found where you least expect it.

Thanks!

Very nice article. Great looking boat.

I’ve never fished Riffe Lake but apparently you have the possibility of adding some landlocked coho salmon to your nettle soup if you can catch one. Then your Huck Finn adventure would be complete.

Thanks, Chris!

Great story, I had to read your earlier 2015 article too! You sure built a luxurious little boat for cruising! Well done, and best wishes for more voyages.

Thank you for a wonderful article. I enjoyed the cruise, but as an amateur boat builder I was left with a strong desire to learn more about HESPERIA.