I work as a naval architect designing high-speed naval craft in an office where the engineers and the most senior naval architect all have the same credo: Never own a boat you can’t carry. Given my career, I felt it was my duty to build a boat with my son and daughter. I considered designing the boat—I certainly have the technical skills—but thinking I could get the design spot-on on the first try seemed hubristic, so it just made sense to go with a proven design. The Chester Yawl fulfilled many prerequisites and needs.

My home in Norfolk, Virginia, is just 250 yards from the shore of the Chesapeake Bay, so I usually hand-launch my boats from the beach. I also have two teenagers, so I need boats big enough to include them on my outings; my rule is to own only boats that I can launch with a dolly, so we needed a boat in the 150-lb range.

Length would be limited to 15′—my garage is 19′ x 19′, and we’d need room to walk around the boat while building it—and a rowing boat would be the best addition to the fleet. I already have two small sailboats and didn’t need a third; and I didn’t want a canoe because its paddlers are facing the same direction, not ideal for conversation. With a rowboat, I could take to the oars and chat with a passenger sitting in the stern. The boat had to be able to handle some waves—the southern end of Chesapeake Bay can quickly turn into a mess of 1′ to 2′ waves when the wind picks up. I wanted an aesthetically pleasing boat with some built-in flotation and the ability to self-rescue if needed. I also wanted an interesting project, not, for example, a single-chine hull we could throw together in a single weekend. And finally, it had to have an aesthetically pleasing, classic shape—I wanted an heirloom, not a workboat.

Robert Bice

Robert BiceThe plank pieces are joined with precise finger joints for proper alignment.

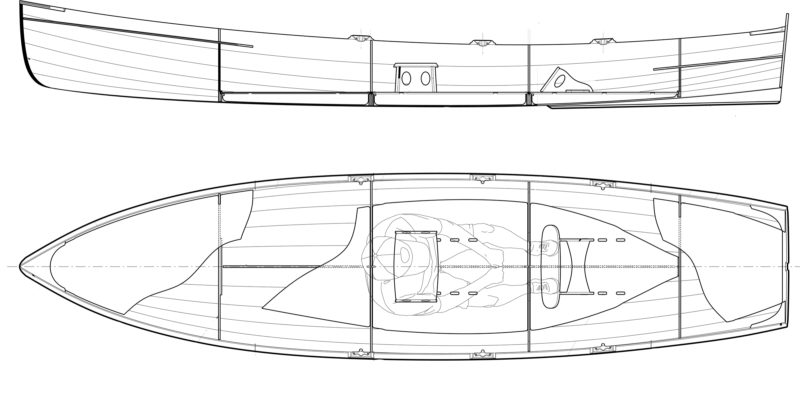

My search led me to Chesapeake Light Craft’s (CLC) Chester Yawl, a 15′ Whitehall-type rowboat. It has beautiful lines, and the complexity of the project seemed just right: enough to feel like an accomplishment without being daunting. The Complete Rowing Kit I ordered from CLC included CNC-cut parts of marine okoume plywood, epoxy, fiberglass, oarlocks, and a 68-page manual. I also ordered the optional second seat. To create full-length pieces, the rubrails have precut scarf joints and the plank pieces have tight puzzle joints that assure that the mating pieces are properly aligned and the curves of the planks will be fair.

I ordered the kit in June 2015 and scheduled a week off from work for the build. I told my wife and kids we would be halfway done by the end of that week and finished by August. I got the month correct but not the year. We launched the boat in August 2016.

Robert Bice

Robert BiceWhile the kit outfits the Chester Yawl for fixed-seat rowing, the open cockpit and the easily driven hull are also well suited for a sliding-seat rig. CLC offers instructions for installing a Piantedosi rowing rig.

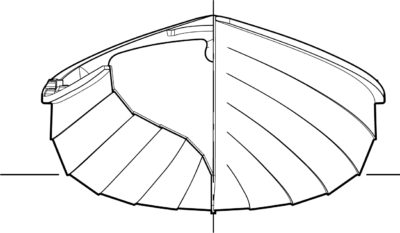

The Chester Yawl build uses CLC’s LapStitch construction, with precut rabbets in the planks’ lower edges to make the laps of adjoining planks self-aligning and create the appearance of traditional lapstrake construction. The gains that taper the laps and bring the forward ends of the planks have to be cut using a guide and a small rabbet plane. The hull consists of 12 strakes. For strength and abrasion resistance fiberglass cloth and epoxy were applied below the waterline and along the stem.

Building the yawl was just challenging enough without getting frustrating, and the assembly turned out to be easier than the sanding and finishing. We used the tricks outlined on the CLC website for smoothing the fillets with denatured alcohol. After the epoxy has cured enough to stiffen, you can put on a glove, dip a finger in denatured alcohol, and quickly smooth the fillet without the hard work and dust of doing the job with sandpaper after the epoxy has fully cured.

After we had started construction of our Chester Yawl, CLC came up with an option for a spacered inwale, which would provide additional stiffness in the gunwales, add easy attachment points for fenders and lines, and create a look that was too tempting to pass up. To accommodate the addition of the new inwales, I had to cut the breasthook and quarter knees out, and notch the frames and bulkheads.

Buying a kit was the best decision I made, as it is unlikely that I would have been able to cut the planks correctly. The most thoughtful part of the kit was that the holes for the stitching wires were predrilled. That made the construction much easier and made for a neater-looking finished product—it’s not easy to eyeball and space hundreds of wire holes. All of our labor—mine and the kids’—was a bit over 400 hours, and it was wonderful family experience.

SBM

SBMThe slots in the center and aft floorboards are for the foot braces, not for the seats, which are held in place by the weight of the rower. The frames are flush with the floorboards in the middle of the boat, providing a place to stretch out. (This is a very early version of the Chester Yawl and some of its details aren’t representative of CLC’s current version.)

The boat has three removable plywood floorboards that fit between the frames. The center and aft floorboards each have rows of notches to anchor footboards. The five notches in each row are 2” long—to fit the tabs on the bottom of the footboard frames—and spaced on 4″ centers, so the footboards offer a 16″ range of adjustment in 4” increments.

SBM

SBMThe support frames for the foot braces have tabs to fit in the floorboards slots.

The foot braces are solidly anchored, and the footboards are set at a comfortable angle. At 5′ 10″ tall and 180 lbs, I have no issues with the width of the floorboards. They appear to me to be wide enough for someone larger as well. I often row barefooted and enjoy the feel of the varnished wood under my feet.

The seats don’t have tabs to fit in the floorboard slots and are held in place by the weight of the rower. Surprisingly, they don’t move while rowing, and I can only adjust the seat by taking most of my weight off it. There is a trick to get the seat in just the right position, because inevitably the seat moves a wee bit as I sit down. After a few tries I was able figure out how to place the seat so that it is perfectly positioned when I do sit down. I like the flexibility of adjustable seats compared to a fixed thwart. The curve of the plywood top takes a bit of pressure off the tailbone at the finish of the stroke.

There are flotation compartments at the bow and stern. The stern compartment is enclosed and has a 1″ drain plug; the forward compartment has a 6″ deck plate in its bulkhead for access and ventilation.

Robert Bice

Robert BiceThe Chester Yawl’s Whitehall ancestry is made clearly evident by the wineglass transom. The partially closed notch captures a sculling oar and keeps it from lifting away.

The sculling notch in the transom is partially closed to help keep the oar in place. I don’t yet have an oar well suited for sculling the yawl, so I have sculled just once with one of the oars we use for rowing. I was barefoot on a wet and slippery floorboard, but even then, the boat was stable and it was somewhat like a stand-up paddle board. I am looking forward to installing some nonskid on the floorboards this spring.

Robert Bice

Robert BicePropelled by two rowers, the yawl can easily reach 5 knots.

We have been using our Chester Yawl for two full years now, and it rows wonderfully. When I’m alone on the boat with just a small ice chest aboard, I can row all day at 3 to 4 mph. It rows well with two people at the oars and easily reaches a top speed of around 5 knots without much effort. My favorite way to row is to use the forward rowing station while having a conversation with someone sitting on the aft seat. My kids like the boat for fishing and messing about.

While it’s a pleasure to row the Chester Yawl, one of the things I really like about it is that the floorboards cover up its shallow frames, and with the seats and foot braces moved out of the way, it creates an open space perfectly suited for an afternoon nap.

If you’re looking for an attractive lightweight rowboat, I don’t know that you could find a better design. I couldn’t ask for more—the build experience was fantastic, and we love the boat.![]()

Robert Bice, P.E., grew up in southeastern Texas and spent his childhood exploring and camping on the banks of Village Creek, a tributary to the lower Neches River. He graduated from Texas A&M in 1995 and has been a practicing naval architect for 24 years, primarily focusing on hull structure and stability. He lives in Norfolk, Virginia, with his two teenaged kids. In his free time he likes to explore the endless backwaters of the Chesapeake Bay or use Google Earth to plan his next adventure.

Chester Yawl Particulars

[table]

Length/ 15′

Beam/42″

Capacity/450 lbs

Dry weight/100 lbs

[/table]

The Chester Yawl is available as a kit from Chesapeake Light Craft. The kit with wood parts alone costs $1,135; the complete kit, which includes epoxy, fiberglass, oarlocks and sockets, costs $1,650. The kit for the spacered-inwale option is an additional $349, and the second rowing station parts are available for $69. CLC provides free instructions for the installation of a Piantedosi sliding seat with outriggers.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Monthly readers would enjoy? Please email us!

What a great, salty-looking boat!!

Beautiful boat and well executed. I’m sure she will provide years of fun. Congratulations.

This design is part of a generation of true recreational rowboats that was inspired by the Oarmaster Trials experiment, held each year on Cape Cod in the 1990s. Among the fundamental discoveries of the Trials was that, for recreational purposes, a well-designed 100-lb boat could do everything better and easier than a 200-lb one. Today, except at museums, it is rare to see a new replica of a heavy, 19th-century oar-powered workboat. The boats we’re seeing most often weigh between 70 and 125 lbs., have waterline lengths between 14′ and 16′, rounded hull sections and molded beams under 4′. This trend is a direct result of Trials winners and high finishers dominating the long-distance, fixed-seat, open-water racing scene in the mid-1990s. Those boats were not racing craft, but rather they are versatile, family-friendly designs that offer a level of performance and convenience that workboat replicas never could.

I own the more rugged Expedition Wherry also by CLC. You are 100% correct on the plans and thoughtful features the fine folks there put into their boats. I love my Wherry. If you are in the Annapolis, Maryland, area, they will be having an open house there on the 17th and 18th this May.

Thanks for the nice write up on the boat, and the information about where you use it. Very helpful, we plan to explore that area a bit, having family in Suffolk, Virginia.

Cheers

Clark and Skipper

I built a Chester Yawl about a decade ago. It regularly cruised the Potomac River but also saw the Atlantic and Pacific as well as other rivers and lakes. I was particularly happy with its ability to work through choppy waters even when in a trough deep enough that you can’t see the shore. Beaching through the surf always presents a challenge in any rowing craft but the Chester Yawl’s higher lines resulted in keeping it on top without worry of catching the bow in the sand as can happen with shorter sheer, pointy bows.