After years of building and sailing open camp-cruiser sailboats, my wife, Anne, and I had become less enchanted with crawling around under a tent at anchor. We were also noticing that over the course of our 30 years of sailing, conditions had changed: Canadian summers were hotter and midday winds were undeniably stronger. Spending time in our smaller open boats was no longer the simple, easy fun it once was and, while it might be hard to admit, we were no longer two sprightly 30-year-olds. It was time to look for a bigger boat.

Gunkholers at heart, we didn’t want to give up sailing in the shallows. So, we were not looking for a fixed-keel boat. We were looking for a boat that could stay on a home mooring most of the time, but we still wanted to be able to trailer it for short trips away. Finally, we wanted a boat with a low-aspect rig and a comfortable cabin.

Matt Singer

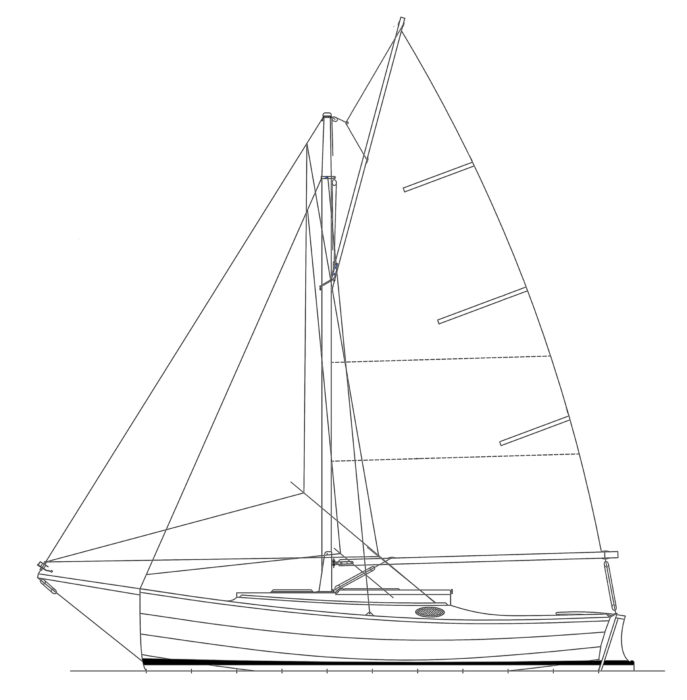

Matt SingerDistinctly British in appearance with its wide lapstrake planking, straight stem, mild tumblehome, and traditional gaff-cutter rig, the Cape Henry 21 is nevertheless all-American as its title—it was named after the headland at the southern end of the mouth of Chesapeake Bay.

Years ago, we had come across drawings of Dudley Dix’s gaff cutters, the Cape Henry 21 and the Cape Cutter 19. We remembered them now and, digging them out again, still liked what we saw. More research revealed both to be solid sailboats, self-righting and self-bailing, shoal-draft yet capable of coastal cruising. We were sold. We decided on the larger Cape Henry (CH21) and commissioned Keith Nelder at Big Pond Boat Shop, Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia, to build the basic hull. We would take care of all the spars, hatches, paint, varnish, and finishing ourselves. The partnership worked perfectly: Keith delivered the bare hull in nine months—on time and on budget—and six weeks later we launched ELVEE into our home waters of Mahone Bay.

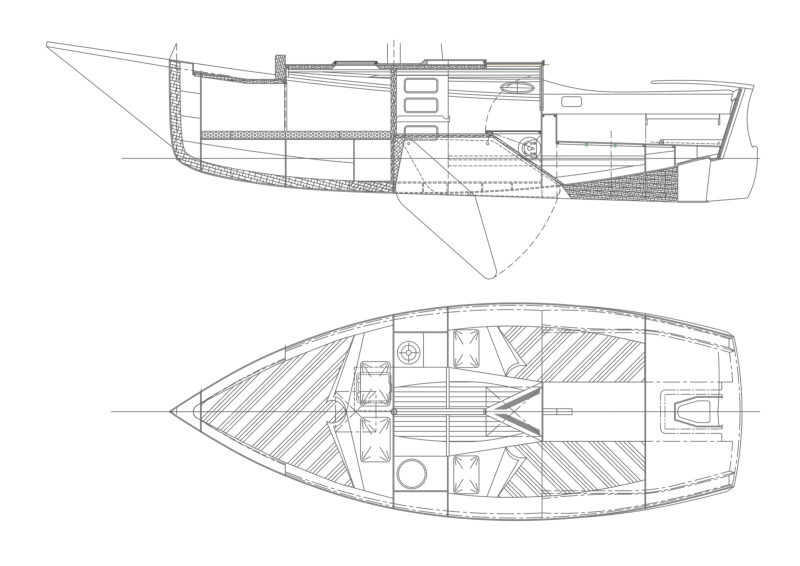

The CH21 can be built by an experienced amateur builder. The plans are very detailed, but I would highly recommend getting a CNC-cut kit. Such a step will make little difference to the overall cost of the boat, but the precision-cut panels make assembly much faster and easier. Even with the kit, I would put the required skill level for building the CH21 at “above beginner.” At the very least a builder will need good woodworking skills and confidence in reading plans.

The hull, four strakes of 10mm plywood, is built upside down on a form with stringers that will reinforce the laps. Diagonal kerfs cut halfway through the plywood on the inside faces of the garboards ease the twisting at their forward ends. Thickened epoxy later fills the kerfs. The result is a strong, light boat. The plans list all the hardware required including the tabernacle, chainplates, motor mount, centerboard, winch, and other odds and ends. Internal ballast consisting of 816 lbs of lead-shot ballast set in epoxy either side of the centerline provides additional stability.

Ryerson Clark

Ryerson ClarkThe Cape Henry 21 has a reputation for being a good performer in most wind conditions, especially in light airs when it will ghost along while other, larger boats struggle to make headway.

The CH21 is a remarkable sailer. Dudley has said that it will sail in wind that won’t even move smoke, and we have experienced just that. Often, our Cape Henry will be making slow but steady headway while bigger boats are drifting to and fro with the tide. It is a dry boat. We seldom get water or spray aboard, and with its fine entry it cuts through waves and wakes with ease. The powerful high-peaked gaff rig and headsails make the CH21 easy to balance, and much of the time it steers itself with just a light touch to the tiller if a correction is needed.

There are two headsail options: staysail with genoa or staysail with yankee jib. With the genoa the CH21 is considered a sloop, with the yankee a cutter, but in either option it is designed to set two headsails at once, except when reaching. We have used both options and are unable to state a preference. We don’t change them out on a day-to-day basis; instead, we set one combination for a whole season and leave it at that. Both genoa and yankee are tacked to the end of the 4½′ bowsprit, while the staysail is rigged inboard on the forestay. In a light to moderate wind, we will use either genoa or yankee, but when the wind becomes stronger or gusty, we will furl the larger headsail and bring out the staysail. As the wind builds further, we reef the main as needed and the boat remains perfectly balanced under staysail and the main with two reefs.

As drawn, the CH21 carries a 6-hp outboard in a motorwell where it is out of the way and beneath the tiller. We have used both a 2.3-hp and a 4-hp gas outboard but have recently converted to an ePropulsion 3-hp (equivalent) electric outboard. Each of the three engines moves the boat effortlessly, and the hull slips through the water with ease. We also scull with our version of a yuloh, a Chinese sculling oar, which we store in the cabin for backup propulsion. Unhindered by wind or current we can scull along at just under 2 knots.

Ryerson Clark

Ryerson ClarkThe cockpit is spacious and comfortable for two adults and a sleeping dog. The sole grating is a later addition to keep feet dry when water comes into the cockpit from the outboard well. The electric outboard has replaced the 6-hp gas outboard recommended by the designer and has proved more than adequate when called upon.

We have been happy with the outboard-well arrangement. It keeps the engine easy to handle and does away with the need to hang out over the transom. The cockpit self-drains into the well, although we have found that when heeled and going hard to windward, the well can scoop seawater into the cockpit, but never more than just enough to wet the bottoms of our feet. We have resolved this issue by building a cockpit grating that not only looks nice and “shippy” but also keeps our feet dry.

The cockpit is large enough for four adults when daysailing, and for a crew of two there is enough space to really stretch out on the long, wide seats—a comfortable spot for an afternoon nap. We made a screened tent that hangs from the boom and covers the cockpit; it gives us an additional mosquito-free living area when at anchor.

Ryerson Clark

Ryerson ClarkTwo quarter berths stretch aft beneath the cockpit. In the main cabin the berths double as comfortable seating. The centerboard trunk divides the main cabin but does not make the space feel cramped. However, a bilge keel version of the Cape Henry 21 is available.

Down below there are two large quarter berths that extend aft beneath the cockpit seats. At 7′ 3″ by 24″ they are long enough for even the tallest of sailors, and wide enough that you don’t feel jammed in. The berths run forward into the main cabin area and offer extremely comfortable seating for two; four friendly adults can sit without feeling too crowded.

Ryerson Clark

Ryerson ClarkIn the galley area there is space for a sink, stove, and plenty of locker space. Forward, the V-berth has more storage beneath and, to starboard, a composting toilet. The flush-decked cabin has full sitting headroom out to the sides.

There is space for a built-in stove on one side of the cabin and a sink on the other, with storage above and below. But this is a flexible space that can be arranged in various configurations and, if preferred, owners can forgo the fitted stove and cook in the cockpit on a portable stove instead. Up forward, the V-berth is 6′ 3″ wide and 7′ 3″ long and has ample storage space beneath for extra gear. We have a composting head beneath the V-berth to starboard.

The cabin is flush-decked, providing full sitting headroom right out to the sides of the cabin. We have found living in the cabin for weeklong trips is easy, comfortable, and roomy. Indeed, guests are always surprised by the spaciousness down below. The only alterations we have made have been slight adjustments to the storage and berth arrangements.

We have daysailed our Cape Henry 21, christened ELVEE, in sheltered harbors and bays, shallow coves and inlets, and have used her for extended coastal trips along Nova Scotia’s rugged coast. We are pleased with her performance and happy that, thanks to her, we have surely extended our sailing for many years to come.![]()

A founding member of the The Small Wooden Boat Association of Nova Scotia, Ryerson Clark and his wife, Anne, have built 20 wooden boats, ranging from kayaks to small sailboats, while also helping countless other people get started on their own boatbuilding projects. During the sailing season Ryerson, Anne, and their dog, Maggie, can be found aboard ELVEE, exploring Mahone Bay and along Nova Scotia’s coast.

Cape Henry 21 Particulars

[table]

Length on deck/20′ 11″

Sparred length/25′

Waterline length/19′ 10″

Beam/7′ 11″

Displacement/3,197 lbs

Draft, centerboard up/1′ 7″

Draft, centerboard down/4′ 5″

Sail Area, mainsail and genoa/ 306 sq ft

[/table]

Plans for the Cape Henry 21 are available from Dudley Dix Yacht Design for $500; study plans, $45.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Having followed Mr. Clark’s other writings and photos, I’m wondering if the editors of SBM could encourage Mr. Clark to do an article about Elvee’s hand-made hardware. It’s the perfect addition to a magnificent boat.

Beautiful little craft. It is clear that you have taken great care in designing the interior for an enjoyable cruising experience.

From the photo it appears that your outboard is an ePropulsion Spirit 1.0. At a nominal 3 hp this is half the horsepower recommended by the designer. As I am building a boat of comparable displacement I would be very interested in hearing more about your experience with this motor.

Andrew

Andrew, this is another reader here, not the owner of this lovely craft….

I have the same motor on my Swallow boats in the UK. It pushes the short gunter rigged 20′ Bayraider well, even in a moderate headwind.

The same is not true when it is on my larger 23′ Baycruiser with its much taller fixed sloop rig, and a little more windage on the topsides and cabin.

Basically, it is a motor suited to moving larger boats in a calm, but not for getting home up a river to windward on an ebb tide.

I sail both my boats 99% of the time so it works for me. I plan to switch it out for my 6hp 4-stroke when cruising tidal coastal waters on the Baycruiser.

Mark, your experience gives me confidence that this motor will be satisfactory for my needs.

Although the boat I’m building has a displacement of about 1800 pounds, it is an 18′ balanced lug yawl with a low-profile hull.

Nice-looking boat, well fit out. A lot of thoughtful design and outfitting in those photos. Thanks for sharing the knowledge.

Cheers

Clark and Skipper