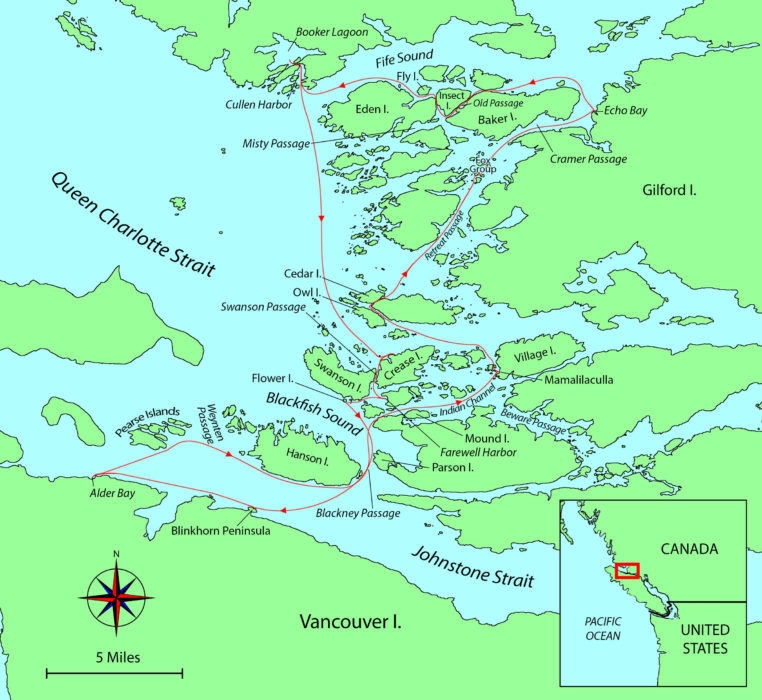

In September 2014, Tim, Alex, James, and I launched from Alder Bay, near Port McNeil, at the north end of Vancouver Island. Each of the four of us brought our own open wooden boat, built with our own hands: Tim with BIG FOOD, a John Gardner-designed peapod; James with ROWAN, mostly an Iain Oughtred-designed Sooty Tern; Alex with HORNPIPE, a modified Don Kurylko-designed Alaska; and me with BANDWAGON, a Hvalsoe 16 of my own design. All of the boats were designed for oars and sail and rigged as lug yawls. We were headed for the Broughten Archipelago, on the southern rim of Queen Charlotte Strait, positioned between Vancouver Island and the remote, mountainous British Columbia mainland.

We were having an easy sail along Hanson Island on the north side of Johnstone Straight when an orca crossed through our fleet and swam between Tim in BIG FOOD, left, and Alex in HORNPIPE, right.

We began with a 2-nautical-mile crossing to the wooded, low-lying Pearse Islands, and headed east by southeast. Immense whirlpools and gyres boiled up near Weynten Passage at the north end of Johnstone Strait. Our course described long, lazy arcs through and around the edges of broad upwellings, spinning around one way, then another. A pleasant breeze filled in as we skirted the south shore of Hanson Island. Several orcas passed close by, heading northwest.

From left, HORNPIPE, BIG FOOD, and ROWAN approached the south end of Hansen Island. ROWAN has the longest waterline of the bunch and tended to sail at the head of the pack depending on James’s whim. My BANDWAGON’s boom is run well out to port.

We slipped through Blackney Passage and crossed the bottom of Blackfish Sound. Alex led the way to our first overnight stop at Mound Island. In woods behind the well-hidden beach I found a cozy tent site where moss padded the earth and lichen hung from cedars and hemlocks.

Shoehorning four sail-and-oar boats with clotheslines moorings off the beach at Mound Island was pushing our luck. ROWAN came up with the short end of the stick. The anchorage appeared snug but adequate with the high tide at day’s end—not so much. In the early morning after the 15′ tidal swing that left ROWAN high and dry on a foul bottom.

In the morning the falling tide had shrunk our anchorage to the size of a swimming pool. James, who had been sleeping aboard, was roused when ROWAN’s stern hung up on a drying rock. He was rattled by his precarious predicament, but ROWAN suffered no significant damage and he quickly recovered his senses and good humor.

A gentle sail of 4 nautical miles along Indian Channel brought us to the old Mamalillicula town site on Village Island. We glided into the inner harbor, where a narrow beach of brilliant white shells fronted the brush-covered embankment. A well-beaten path just above the bank carved its way through brambles and grasses. Two huge silvery, adze-textured cedar posts, rising up above the thick undergrowth, held overhead a great beam, the remains of a native longhouse. Nearby, a two-story building of weathered clapboards was framed by vines and creepers. Farther along the path an aged totem pole lay on the ground, the carved features barely discernible; moss and delicate fern flourished over its gentle folds. Silent, dense green forest edged the clearing.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

We rowed west to Owl Island and pulled into a small kelp-armored nook. The beach was soon cluttered with our lines and pulleys as we jostled clothesline moorings to keep the boats afloat and clear of each other on the overnight low tide. With the chaos sorted out and our boats secure, we explored the island. A path led overland under towering spruce and cedar trees, through salal and understory growth, bathed in infinite shades of cool green light. On the seaward side, stunted pines and fir clung to the foreshore above jumbled driftwood and tidepools.

The next morning, we weighed anchor and moved out along Cedar Island. My attempt to sail against wind and tide in the narrow channel left me lagging far behind the others. I took to the oars and pulled hard to catch up. Just as I spotted Tim, James, and Alex again, they seemed to vanish into a solid wall of rock. I followed, through a narrow passageway just wide enough for our boats to pass through one at a time. This yards-long slot near the north end of Cedar Island led to the open water of Queen Charlotte Strait with a strong westerly blowing along its 40-mile fetch.

Waves deflecting off the shoreline piled upon each other and rocked the boats like bucking horses. We tucked in multiple reefs, raised sail, and surged northeast across the swells toward Retreat Passage, the wind on the port quarter. Regrouping among the Fox Group, a cluster of islets sprinkling the far end of the Passage, we sheeted the mizzens in to point with our bows into the wind and dropped the mainsails. The high eminences of Gilford and Baker islands loomed to the west and north.

After a lunch break, we raised sail again and continued eastward through Cramer Passage. The wind strengthened as it funneled between the two islands. BANDWAGON felt on the verge of a knockdown. Once again I sheeted the mizzen, threw the helm back, and dropped the main as the bow swung into the wind. Even after tying in another reef, my hands were full as the rig started drawing again. I managed to careen along the last bit of the passage and into the opening of Echo Bay.

With BIG FOOD and ROWAN tied up to the wharf at Echo Bay, the steep ramp and barnacled pilings indicate a low tide. The ramp leads to a spacious meadow and a path continues to the right to other parts of the settlement. BIG FOOD’s stern shows her kick-up rudder, boomkin, and push-stick steering arrangement.

We eased up to the sturdy, though somewhat neglected, government wharf at the head of the bay. Its pontoons floated lazily at odd angles and grass grew in the gaps of the decking. On the north side of the bay, docks and a few modest floating cabins with bright red, green, and blue metal roofs backed up against a 100′-high cliff of fissured grey rock. The half-dozen finger piers of the marina opposite were nearly empty. Operations were largely shut down for the season: only a handful of other vessels lay scattered about, and the cabins were quiet.

A ramp led from the dock to shore and a spacious meadow with scattered cedars and firs. The place was just right for camping. A short walk from the meadow sat a modest single-story building, used as a schoolhouse in earlier times, when small thriving communities supported by logging and fishing dotted the British Columbia coast.

After tidying up the boats and claiming tent sites, we followed a trail across a 100-yard-wide peninsula to Billy Proctor’s sprawling homestead at the foot of the adjacent bay. Set apart from his home, museum, and gift shop, an arched, shingled boathouse and shipway looked like nothing so much as an inverted boat hull. After perusing the gift shop, we made our way back along a steep trail to Echo Bay and Pierre’s marina where we found the restaurant closed and the store’s shelves nearly bare. We were able at least to bolster our supply of drinking water. Back at the government float, James and Tim hauled in their traps, which held a catch of Dungeness crab and not the more-common rock crab they’d expected. Boiled on James’s powerful white-gas stove, this signature northwest delicacy was served for dinner alongside our boats that evening.

Tim rowed in the glass calm typical of of our early morning departures. The westerly breeze would regularly come up in the afternoon. After our Broughton trips, Tim switched from BIG FOOF to HAVERCHUCK, an 18-footer he built to my design.

Departing Echo Bay in a light fog the next morning, we rowed north then west along Baker Island, its vertical walls of multi-hued conglomerate rock washed by the 15′ tidal range. Tim and I bore away to the southwest and pulled hard against a foul current through narrow, mile-long Old Passage. Around midday we met up again with James and Alex between Eden and Insect islands. We pulled up to a narrow strip of beach on Insect Island. A signboard on posts at the edge of the beach implored visitors to respect First Nations land and territory.

At high tide on Insect Island, we took a break next to a First Nation’s sign requesting “Respect Our Land,” which we endeavored to do. Access to Insect Island is now limited, but there is plenty of gunkholing, and other anchorages in Broughton Provincial Park. Among our group, beach chairs are mandatory and provide a welcome measure of comfort on the shell-midden beach. The wooden box is James’ cooking kit.

Treading lightly, I walked across the soft luxuriant forest floor, thick with needles and duff. Logging had left most of the island covered with second-growth forests but huge trees remained, crowding out sunlight from the interior. Fallen giants spanned broad ravines and hollows. The land above the beach was steep, providing wide-ranging views northward over the surrounding wooded islands and channels to Queen Charlotte Strait. In the afternoon I went for a sail in the fresh breeze, exploring Misty Passage. That night I put BANDWAGON on her mooring and slept ashore; I used every bit of my 400’ clothesline to keep her afloat beyond the shallow shelving beach.

I anchor BANDWAGON with the mizzen set as a riding sail. My clothesline mooring has a blue buoy attached to the anchor and a yellow floating retrieval line, which passes through a ring on the buoy and runs in a loop from the boat to shore.

The next morning, after a light breakfast and stowing anchors and clothesline gear, we rowed quietly north and west through narrow passages separating Fly and Eden islands. Already the air was warming and ruffles of wind tickled the water’s surface. Tim and James paused for a spell with their rods and lures.

As the four of us spread out over the wider waters of Fife Sound, two humpback whales cruised along the perimeter of the waterway. Rowing well out in the middle, I entered a broad area of tidal upwelling; the two whales began crossing from the west shore to the east, seeming to make a beeline for me. Their arched backs slid across the water’s surface, the immense tail flukes slowly following in a graceful and powerful arc.

The pair dove and resurfaced very close to BANDWAGON, at times within yards. They came from one direction, then another, sometimes each from opposite sides. Spinning around, I tried to identify a pattern of movement so as to steer clear, and eventually backed out of the upwelling. Only later, after the adrenaline subsided and my head cleared, did it occur to me that I had been sitting right atop the humpbacks’ dinner table. The upwellings were stirring up a rich stew for these giant filter feeders.

A large humpback trailed BANDWAGON in Fife Sound just off the logged slopes of Broughton Island. We heard or saw humpbacks nearly every day, but they never came so close to us as in Fife Sound.

In the late afternoon, after 5 or 6 miles of parched rowing and sucker wind holes, we reached Cullen Harbour. It was high tide and Alex had arrived first but found no feasible campsite or haulout around the perimeter of the bay. We would have to try the lagoon just out of sight to the northwest. With high slack water, Booker Passage, the 1/4-mile-long easternmost entry into the lagoon, was calm. I followed James as he entered the passage then took a sharp right turn into a narrow opening where the forest canopy closed over our heads. A strong current set against us, and in the dappled light oar blades kissed the tree-choked banks.

After a couple of minutes, the tunnel opened up and we coasted into Booker Lagoon. Two miles long east to west and more than a mile wide, the lagoon was expansive, and as still as a millpond. Dense foliage and sagging evergreen boughs hugged the water’s surface, giving the impression of an overfilled tub. To port was a flat-topped rock islet. Tim and Alex, having taken a slightly different route into the lagoon, came around the corner. We brought the boats gently to rest on stony ledges. The islet was not much to camp on, but a fine place to have dinner after a long day.

We arrived in Booker Lagoon with the high tide at the end of the day. As the lagoon drained with the ebb, we had to shuffle the boats around as the rock dried. The white shape in the distance is a motor yacht at anchor. It surely would have taken local knowledge to get a vessel that large safely in and out of the lagoon.

The late-afternoon ebb began to draw down the water in the lagoon. Between bites of food, we shuffled the boats around to keep them from going high and dry. Our rock platform grew and its sides began to fall away steeply. With dusk approaching, we clambered back down to the boats. Each of us stole away to drop the hook for the night. I carried more than 100’ of anchor and rode; all of it went overboard. Not a lick of wind ruffled the surface. As an orange glow faded from the western sky, I slung my tarp between main and mizzen masts and set the alarm for predawn to catch the next morning’s slack.

After being rousted by the morning alarm, I rose from my sleeping pad on the gently curving floorboards, slipped half out of my bag, and fired up the stove for a cup of oatmeal. As I stowed the tarp, the stars began to fade away and the eastern sky brightened. I coiled ground tackle into the forepeak and lowered the spars for the row out.

The four of us slipped toward the mouth of the lagoon. An unfamiliar noise began as a faint whisper. I rounded a corner and took a look at the outlet stream, so calm when we had entered the previous afternoon, and the whisper became a roar. We had extrapolated the tides for Cullen Harbour from the tables but we could only guess at when and how the water might flow out of Booker Lagoon and its two narrow outlets.

The channel was a whitewater tumult. Thinking it may only get worse, I took a deep breath and thrust into the maelstrom. With my legs braced and a firm grip on the oars, I ferried across the current in whitewater fashion, stern first, bow pointed against the flow. After a quick few hundred yards the rapid deposited BANDWAGON into the north end of Cullen Harbour, and I pulled into an eddy beside a large rock to watch the other boats sweep through.

The morning had barely begun. We rowed out to the mouth of the bay and gazed upon the open water of Queen Charlotte Strait. The sun warmed the chill air as we rafted together for morning coffee.

To seaward, the dark silhouettes of two humpbacks appeared, possibly the pair we had seen the previous day, one enormous with immense flukes as broad as my boat is long. Arcing in slow motion, the pair moved as if in a choreographed ballet. In the stillness of the crystalline morning, within a few hundred feet of our floating congregation, the large humpback leapt for the sky. After extending nearly its full length above the water, it fell back into the sea with a thunderous boom and eruption of spume and spray. We sat in dazed silence, coffee cups motionless in hand.

From Cullen Harbor, the four of us fanned out across Queen Charlotte Strait to rendezvous again 9 miles to the south at Crease Island. James skirted closely along the Broughton Archipelago. Tim, Alex, and I chose a more direct course toward Swanson Island, a little over 8 nautical miles distant, leading us out into open, glass-still water. In the midst of a sun-soaked rowing stupor, I became aware of a distant splashing sound. Nearby, Alex was already standing up and gazing across the water. I looked east and all around the water was dappled with splashes. We were in the midst of a massive school of Pacific white-sided dolphin, as far as the eye could see and traveling northwest. I sat for several minutes taking it all in, surrounded by the sounds of dolphin.

Tim and Alex pulled through Swanson Passage as we headed south, back to Vancouver Island, which towers in the distance. After this trip with HORNPIPE, Alex built a new sail and oar boat, FIREDRAKE, to his own design and has since cruised extensively with it.

Off the north end of Swanson Island several clusters of islets, rocks, and shoals turned the calm water into a confusing mix of rips, eddies, and upwellings. We made our way through the turbulence and continued south; a pleasant following breeze sprang up. Tim, Alex, and I had yet to spot James. We passed a cove on the north shore of Crease occupied by a motoryacht, and continued eastward along the edge of the island as the day waned. The three of us landed at a small beach with a rock-strewn approach, pulled the boats above the high tide line, and settled in for the night. I bivied among the driftwood on the beach and under the stars fell into a deep sleep.

It was an early-morning call the next day to get the boats off before being trapped by the falling tide and obstacle course of rocks. With mighty heaves we pushed the three boats down the rough beach and into the water, getting away just in time.

As we made our way back toward the anchorage passed by the previous afternoon, we found James and ROWAN standing off the point. It seems he had been in the anchorage all along, obscured from our view by the motoryacht. He had avoided our mad morning dash; we avoided the noise of his neighbor’s generator in the anchorage.

Continuing south around Crease Island, we pulled against the current through Swanson Passage. Mist clung to the verdant shores of Crease and Swanson islands. To starboard, larger vessels lay in fog-shrouded Farewell Harbour. The ebbing current exposed a rich intertidal zone that popped and hissed. Slowly the fog burned off, and as we rounded the bottom of Swanson, we pulled inside the bight of Flower Island. Thick kelp beds provided a handy mooring. It was now a waiting game to pick a time to negotiate Blackney Passage, one of a handful of constricted exits for the ebb-powered flow of Johnstone Strait.

Eventually we cast off and made our way a couple of miles to the north end of Parson Island. While the current still ran strongly northward through Blackney, we inched south, rowing along the steep shores of Parson, playing the back-eddies and fighting through the kelp beds. A raft of sea lions was as surprised to see the four of us as we were to see them. Wanting to leave them in peace and avoid any aggressive behavior, we gave them as wide a berth as possible, but quarters were tight. As the current showed signs of weakening, Tim judged the time right to make a dash west across to Hansen Island. We crossed without difficulty and continued into Johnstone Strait.

The gang spread out across the beach on the Blinkhorn Peninsula. The campfire was ready for cooking and James bent over a big ling cod to fillet it.

A steady northwesterly that afternoon gave us a glorious sail to windward and the Blinkhorn Peninsula, 5 nautical miles distant. For dinner, the 10-lb lingcod James pulled in that afternoon was filleted on a driftwood platform and cooked over the campfire, to be topped off by James’s Dutch-oven biscuits. That night Alex retired to his tent while Tim, James, and I slept soundly at anchor.

At dawn of the eighth day, we pulled home to Alder Bay.

In the morning we rowed west 5 miles in a dead calm along the forest-draped coast of Vancouver Island, back to our launch point at Alder Bay and one of the very few things we had missed: warm showers.![]()

Eric Hvalsoe grew up in a boating family near Seattle, Washington, and got glimpses of the San Juan and Gulf Islands, and northern BC waters, at an early age. He later revisited some of these same destinations, including the Broughtens, in sea kayaks and most recently, traditional sail-and-oar craft. As Hvalsoe Boats, Eric has been designing, building, repairing, restoring, and maintaining wooden boats since 1980. His home and shop are located in Shoreline, Washington. Eric teaches traditional boatbuilding and lofting skills at Seattle’s Center for Wooden Boats. The Center’s collection includes some of Eric’s designs, the Hvalsoe 13, 15, and 16. This family of sail-and-oar designs has expanded to include the Hvalsoe 18. For a while longer yet, Eric hopes to continue exploring the Salish Sea in non-motorized craft.

Travel Notes

A portion of the Broughton group has been designated as the Broughton Archipelago Provincial Park. Find out more about the park and environs, including up-to-date bulletins, from BC Parks. Bring water, be bear-aware, and leave no trace. Campsites, with beach haulouts or anchorages for small boats, are relatively scarce. Weather is variable and can be fierce, so monitor marine-weather-radio forecasts. Be mindful of First Nations ancestral sites. For permission to go ashore at Mamalillicula, contact the Mamalillicula Band office at 250-287-2955. A fee of $20 is required for each person visiting the site. Insect Island, according to a kayak guide service operating in the area, was closed to visitors in 2016. Tidal Waters Sport Fishing License must be obtained from Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Licenses can be obtained online or in person at recreation and sportfishing shops. E.H.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Thanks very much for writing this up, Eric. It brings back memories and it is very interesting to hear the story from your perspective. This trip forms one of the chapters in my new book, and while I remember some of the details a little differently, we definitely were on the same trip!

(Alex’s book is Becoming Coastal. —Ed.)

Hi Alex,

My story did not come from contemporaneous notes, as yours may have. But I think that’s OK.

It is a tale, to the best of my recollection, linking together a number of vivid memories. There were spaces to fill in, helped by reviewing the chart, photos and the WBF thread. No question that memory, mine at least, is an elastic and sometimes confounding thing. I can only hope that in the telling, I captured something of value.

It was a great trip, blessed by fine weather, in the best of company.

Eric

What a great adventure!

I have done the Bowron Lakes circuit in British Columbia twice in a canoe and a rowing dory. I think a salty cruise would be double the fun, what with whales and sea creatures!

Great read! A friend and I kayaked a similar route in June 2019, beginning and ending at Telegraph Cove. Thank you!

Lovely account, Eric. You’re one plucky band of adventurers.

Thanks for the great trip report, Eric. I like the cruising details. What were the calendar dates? And what might be your recommended range of ideal dates? I’m contemplating a similar but somewhat longer trip in my 20-ft. modified Whitehall.