I crawled out of the boat tent as soon as the sky started growing light; a few leftover raindrops rolled off the edge of the tarp and down my back as I wriggled past. I had spent the evening huddled in my sleeping bag reading and looking at charts, shuffling gear around to keep things dry as rain pattered steadily on the tent. With a wide sleeping platform and a tent to keep me dry, my new boat was proving to be luxuriously comfortable, at least by backpacking standards, but September nights on the Great Lakes are long. After so many hours aboard, I was ready to be moving again. I climbed out into knee-deep water and waded ashore.

photographs by the author

photographs by the authorI left my malfunctioning VHF radio in the car and returned to simpler methods of weather forecasting for this cruise—methods as simple as hearing the patter of raindrops overhead. An improvised boat tent and plenty of books helped me wait out the rain at South Benjamin Island.

The morning was clear and cool; the sky had washed itself clean of the thick gray clouds I’d encountered on yesterday’s 10-mile passage from my launching point in Spanish, Ontario. I’d never come to the North Channel so late in the year before. The sun hung low in the sky, casting long shadows across the beach and promising shorter days. A stand of yellow-leafed birches at the edge of the beach shifted slowly in a slight breeze, and an osprey flew past with a faint flumph of wings. A dozen small islands and granite outcroppings rose from the water just offshore, and beyond them was the chain of pink rocks named the Sow and Pigs. Otherwise, nothing. There were no other boats in sight—and this at South Benjamin Island, one of the most popular cruising destinations in the North Channel.

After several hours of sailing to reach the Benjamin Islands, I was ready to leave the boat for a while. A tricky scramble through thick brush and up a steep granite slab led me to this overlook at the southern tip of South Benjamin Island.

By the time I had eaten a bowl of oatmeal, stowed my gear, and had the boat ready to go, a strong northwesterly wind had come up. The open water to the east was a flurry of whitecaps, and the big pines along the shore were shifting and creaking restlessly overhead. A bit uneasy, I rowed through the rocky maze at the tip of South Benjamin and out of the lee of the island. It was windy—maybe too windy for the 20 miles I’d have to sail to reach Bay of Islands, my next planned anchorage. I’d had visions of an easy broad reach and a few pleasant days of sailing to begin with while I learned what my new boat, a Don Kurylko–designed Alaska I’d launched in June, could do. Instead I’d be starting off close-hauled on a double-reefed mainsail. Maybe triple-reefed. Well, I told myself, you can’t always wait for perfect conditions.

With no tides, it’s always easy to get to your boat when you need to. I replaced the mast gate shown in the Alaska plans with a simpler lift-out partner, which made stepping and unstepping the mast from shore a little simpler.

I started pulling out the sail to tie in a deep reef, but stopped a moment later, shaking my head. What was I doing? I wasn’t on any schedule other than a vague plan to sail eastward into Georgian Bay for as long as the weather was good. To set out in conditions like this, triple-reefed, suddenly struck me as asinine. Laughing out loud at my near-stupidity, I set the sail aside, then pulled out the oars. I wasn’t going to raise the sail, but that didn’t mean I had to sit around on the beach waiting for the wind to die down.

I spent the morning rowing up the eastern side of the Benjamins, dodging through the wide band of rocks and shoals guarding the approaches to neighboring Fox Island. The boat, loaded heavily with cruising gear and ballast, took a half-dozen strokes to get up to speed, but kept moving through the waves with little effort and no fuss at all, no surprise for a design modeled on a classic Whitehall hull. With a deeply reefed sail, it would have been a struggle to work my way north. Under oars, it was a pleasant way to keep warm.

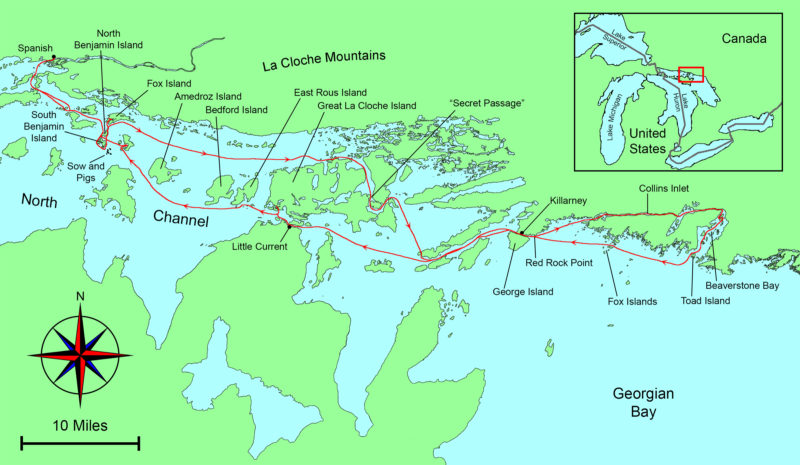

Looking over the chart, here at my South Benjamin anchorage, to pick a destination for the day was my standard post-breakfast routine. With good visibility and no tides or currents, navigation on the North Channel rarely gets more complicated than eyeballing the islands as you sail past.

The west side of Fox Island was all bare-boned ridges, dark pines, and narrow passages cutting through broad expanses of smooth granite. I rowed past the outlying rocks and up into Fox Harbor, a deep inlet I’d never explored before because it was always crowded with deep-draft sailboats and motoryachts. Today it was empty, except for one sloop anchored far up at the head of the narrow bay.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

I worked my way up Fox Harbor, making detours up the many side channels and backwaters whenever the opportunity arose. They were dead ends, I knew from the chart, but still worth exploring. Near the head of the inlet I turned to port into one last dead end that led me to a narrow channel lined with cliffs, barely wide enough for my oars. At a few places, with less than a foot to spare on either side of the boat, I had to trail the oars close alongside the hull and let the boat’s momentum carry me through. And then all at once I was past the narrows and into a wide bay—a bay on the north side of Fox Island, and, according to the chart, completely unconnected to Fox Harbor. I had rowed right through a gap that wasn’t supposed to be there, the kind of unexpected opportunity that sail-and-oar cruising has to offer.

I spent the rest of the day working my way through unlikely passages along the edges of Fox Harbor, slipping through channels so narrow I sometimes had to stand in the boat and paddle with one oar. Summer had been rainy, and water levels were about 3’ higher than indicated on the chart, opening a complex web of passages that would have been dry land on my last trip here three years ago.

With the wind out of the northwest at 20 knots or more, I was happy to spend a day exploring the rocky interior of Fox Island under oars. The narrow channels and sweeping granite slabs provide a good preview of tightly clustered islets of Georgian Bay.

After an afternoon of poking around and keeping out of the wind, I emerged on the south side of Fox Island and followed the shoreline east. After a mile or two, I rounded a corner to find a hidden alcove carved into the stony shore, a tiny bay hardly bigger than my boat. A lichen-spattered granite dome rose 15’ above the water’s edge on one side, with a single stunted pine standing just below its summit. I glided to a stop in a stand of half-drowned willows at the foot of the rocks, tied off to some branches, and waded ashore.

The wind seemed to be dying down. I had a quick snack and wrote some notes in my journal, then set out again under sail. Once out of Fox Island’s lee, though, the wind swept in even stronger than before—too much to face so late in the day. I lowered the sail, dropped the mast, and headed back to the hidden alcove under oars, easier and faster than sailing in this wind. I tied the painter to a stout birch stump, then pulled my gear out of the boat—a single trip, with only two large waterproof duffels to carry—and brought everything up to the top of the dome. I’d arrange things later. For now, leaving the bags at the foot of the lone, sentinel pine, I set out to explore the island. I spent the rest of the afternoon walking broad pathways of bare granite past reed-fringed ponds and forests of white pines and birches. Just after sunset I returned to camp, ate a supper of black beans, tomatoes, and chiles sprinkled with lime juice, then set up my tent at the very edge of the granite cliffs and sat back to watch the darkening sky fill with stars.

Fox Island’s rugged southern shores offer plenty of good campsites overlooking the water, and a pleasant break from sleeping aboard. Here the view is east toward Amedroz Island and the Bay of Islands beyond.

Morning brought blue skies and light winds. I ate breakfast—oatmeal again—and prepped a Thermos meal of red beans and rice for supper. After repacking the boat, I rowed a few yards offshore and raised the sail. After half an hour, though, I’d barely cleared Fox Island, and the breeze was swinging around eastward, forcing me well off my desired course. I dropped the rig and settled in for a long session at the oars. Far ahead, the rugged pine-clad La Cloche Mountains rose from the mainland to the northeast, with a line of big islands—Amedroz, Bedford, and East Rous—forming the southern edge of a broad channel leading eastward. Somewhere just beyond the horizon was Great La Cloche Island and, along its northern edge, the back door to Georgian Bay.

Eventually a westerly wind came up, putting me on a broad reach—perfect sailing. I let my 59-cent autopilot, a simple bungee-and-line tiller tamer, keep me on course. With the wind holding steady, I tied the sheet to an oarlock with a slippery hitch, and sat back to enjoy the ride. The wind grew stronger as I sailed on, the boat surfing the steeper waves with a smooth rush of speed and showing no inclination to broach. Perfect sailing indeed—20 miles of it.

Guarded by extensive shoals and a narrow, winding entrance, this hidden cove at the gateway to the Bay of Islands is a perfect small-boat anchorage. Even in mid-September, the water was warm enough for a brief swim before supper.

When I reached the entrance to Bay of Islands, I turned up into a beam reach and the strength of the wind suddenly became obvious, then made way up the shore of Great La Cloche Island: a dead-end bay for keelboats, but not for my Alaska. Twenty yards offshore I dropped the rig and rowed through a narrow knee-deep channel that led, eventually, to a sheltered bay hidden between a cluster of tightly linked islands too small to be named on the chart.

I dropped my 6-lb Northill anchor from the stern in the middle of the bay and rowed up to shore as the line ran out, cleating off just as the bow edged toward the rocks. Stepping out into knee-deep water, I took the painter ashore, tied the end to a tree, and headed off to explore, but it didn’t take long. The islands were nothing but jumbled heaps of moss-covered boulders that rolled and clattered underfoot, with nowhere to pitch a tent. I set up the sleeping platform and boat tent and got ready for a night aboard.

I woke in the night to the sound of loud splashing and grunting just outside the boat. Bears? I wondered, but dismissed the idea almost immediately—I’d expect a bear to approach from shore, and these sounds were coming from behind me, out in the water. I pulled up the side of the boat tent. Five or six white-whiskered faces were just visible in the darkness. They vanished with a sudden series of huffs and splashes as soon as I poked my head out. A minute later I heard them surface farther down the bay. Otters. They splashed their way out of the cove and the noise faded to silence. I went back to sleep smiling.

Rowing past Great La Cloche Island on a typically calm North Channel morning, I covered more than 10 miles under oars before the wind came up. I was pleased to find my new Alaska as well-suited for the task as I had expected.

Daylight arrived without wind. No matter—I had oars. I pulled out a can of peaches to eat underway, packed up the boat, lowered the mast, and shoved off from shore, retrieving my anchor along the way. Soon I was rowing east along the north side of Great La Cloche Island, slipping along the southern margins of the Bay of Islands. Somewhere a loon called. Farther on, a bald eagle stood on the rocks at the water’s edge tearing a fish apart.

The water was dead flat, and the boat moved smoothly and easily. I was traveling 15’ per stroke, I decided, watching the hull slide through the water. A hundred strokes for 1,500’, 400 for a nautical mile. I pulled out my watch, set it on the bench beside me, and started counting strokes. Twenty minutes later, pulling steadily and easily, I hit 400. Twenty minutes meant 3 knots. And that was moving at an all-day pace, with the oars slipping in and out of the water so silently and smoothly that it felt like the boat was rowing itself. It hardly seemed necessary to have a sailing rig at all.

By late morning I reached the double bridge that joins mainland Ontario to Great La Cloche Island—my secret small-boat passage to Georgian Bay that bypasses the crowds, strong currents, and the open-on-the-hour swing bridge at Little Current on the south side of Great La Cloche Island. The bridges on my route were fixed: too low for even a short mast, and too narrow for oars, making it impassable for larger boats. In my Alaska, all I had to do was pull the oars in close to the hull as we coasted through.

I reached Killarney by early evening, and dropped the sail to row through the narrow dock-lined channel separating the town from George Island. With excellent anchorages just a few miles away at the northern edge of Georgian Bay, I had time for a stop in town to phone home. I pulled the boat onto the grass alongside one of Killarney’s many marinas, called my wife, and bought a few groceries. On my way back across town I treated myself to a local fish fry. As I was leaving, I saw a woman loading some bags into my boat.

“It’s the last day of our trip,” she said as I approached. I hadn’t even asked a question. “And it looked like you could use them in your little boat.”

When I opened the bags I found boxes and boxes of expensive cookies and candies: maple shortbreads maple creams maple peanut brittle maple sugar leaves maple everything. Only in Canada, I thought. And only in Canada would you find people putting stuff into your boat.

There was less than an hour of daylight remaining by the time I left Killarney. Out in Georgian Bay, beyond the end of the narrow Killarney Channel, a strong southwesterly was blowing, sending big waves crashing into cliff-lined lee shores. Not eager to face those conditions in the fast-approaching darkness, I turned back toward town and found a small sheltered bay near the end of the channel, just west of the lighthouse at Red Rock Point. I tied the boat up to a waist-high granite outcropping, slipped a cushion between the hull and the rocks, and set my tent up on a granite slab at the water’s edge.

The little bay was less than a mile outside of Killarney. It might as well have been a hundred. I spent the last of the day’s light looking over the small-craft charts for Georgian Bay, then sat outside the tent on a pile of boat cushions until late in the night, watching the broad belt of the Milky Way fade away with the light of the rising moon before I crawled at last into the tent. I drifted off to sleep to the sound of waves still crashing on the rocks below.

The good weather was holding, but I didn’t trust it. The long low slant of the sunlight, the coolness of the air, the emptiness of the popular anchorages—everything seemed to suggest the end of the season, as if November’s cold winds were waiting in the wings to sweep in and slam the door shut on summer. I didn’t want to be too far from my car and trailer when that happened.

I sailed eastward through Collins Inlet, a narrow cliff-lined passage 10 miles long. With a following wind that grew stronger as the day went on, I kept the boat on a broad reach and tacked my way downwind to avoid unpredictable jibes in the shifting gusts.

I’d left Killarney the day before, sailing a dead run eastward through Collins Inlet, a narrow fjord-like passage that ran for 10 miles along the north side of Philip Edward Island—an inland waterway lined with 50’ cliffs, occasional cabins and cottages, and here and there an outboard-powered fishing boat buzzing past. Now, tacking my way down Beaverstone Bay, the eastern end of Collins Inlet, I knew I’d have to decide soon: continue east to the Bustard Islands, or turn west and begin working my way back toward Spanish.

First, though, I had to find a way out of Beaverstone Bay. After a few false starts among the seemingly endless rocks and reefs, I found what I thought must be the entrance to an intricate boulder-studded passage just west of Toad Island. I short-tacked my way out through the gap, fighting strong winds dead on the nose, surging over steep waves that smashed themselves to spray on half-submerged rocks and shoals all around me. The boat handled it beautifully under full sail—I had learned to expect nothing less. It seemed a long time ago that I had been hesitant to set off from the Benjamins.

Once past Toad Island, I kept tacking out into Georgian Bay to get some sea room, heading south past the outlying rocks until there was nothing but hundreds of miles of open water ahead—a broad blue sky, a flat horizon, and an endless succession of waves rolling in from the southwest one after another, row on row, and row on row, for as far as I could see. Two miles offshore, far enough to be clear of shoals and shallows, I luffed up and released the sheet and let go of the tiller, leaving it to my bungee autopilot to hold us steady while I pulled out my large-scale chart. The boat drifted slowly downwind, rolling and yawing with each wave. I made dividers of my fingers and measured distances. It was 20 miles to the Bustard Islands—three days just to reach the islands and return to Killarney, and another three days back to Spanish from there at a minimum. Add time to explore, and I wouldn’t get back to my car until sometime in October.

Two nights in the Fox Islands gave me lots of time to explore. While circling West Fox Island on foot, I was caught by the play of light and shadows on the wave-sculpted granite.

I finally decided it was better to turn west and start closing the loop. The Bustards would have to wait. Taking a last look out across the open waters of Georgian Bay, I folded the chart and turned off the wind on the port tack, heading east. Close-hauled, I could just hold a course for the Fox Islands. I hauled the sheet in tightly and moved up onto the rail, smiling as the boat surged forward, shouldering past the waves and sending glittering arcs of spray flying over the water. I leaned farther outboard and reached one hand down to skim the surface of the water as we flew along.

North Benjamin Island’s hidden west-side lagoon is inaccessible to all but the shallowest-draft boats. With water levels 3’ above chart datum this year, the channel was less than 4’ deep.

Late that night, on a broad bare summit at the eastern end of the Fox Islands, I unzipped my tent and stepped out into the darkness. I could hear the quiet rush of waves on the slabs below, the ceaseless surge and retreat of wind-driven water that had scoured and smoothed the rock I was standing upon, and would continue to wear away the edges of the islands, slowly shaping them into fair curves and flowing forms until there is no water left for the wind to move, and no wind to move it.

From somewhere within the shadow of the pines a barred owl called. Slowly the northern sky filled with twisting ribbons of green, gold, and white, broad translucent bands of living light rising from the dark horizon in shifting curves to weave themselves together in silence, glowing brighter and still brighter until it seemed the sky was filled with fire.

I stood and watched until the colors began to fade, then made my way barefoot over cool, smooth stone down to the water’s edge where my boat was waiting, anchored just offshore. Her pale green hull, lit by a quarter moon, was mirrored in dark water that rippled and wavered and reformed itself beneath her with each breath of air until it was impossible to see where the work of human hands ended and the endless smoothing and shaping of the wind and waves began.![]()

Tom Pamperin is a writer and small boat sailor based in northwestern Wisconsin, and the author of JAGULAR Goes Everywhere: (mis)Adventures in a $300 Sailboat. He is a frequent contributor to Small Boats Monthly.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

Nice story of a beautiful trip. Nice boat too. Don Kurlyko is a good friend. I like to see his Alaska out in the water.

Thank you for this wonderful report! This is the kind of trip I hope to take with CLARISA, my Ilur, launched just this spring. I was smitten by the Georgian Bay long ago and now your mouth-watering account is responsible for my resolve to follow these lovely liquid lanes sooner rather than later. THANK YOU!

Having sailed with Jeff Saar aboard his Alaska, I have always been impressed by the beauty and philosophy behind Kurylko’s design. You’re probably avoiding public discussion about this subject, but I’m mighty interested in hearing your comparisons between your new boat and the other love of your sail and oar life, the Phoenix III. I imagine it’s too early to say, but I’ll be looking forward to it sometime in the future.

Scot,

Jeff Saar’s Alaska photos on Don’s website were a big part of the reason I chose an Alaska! As for comparisons with Ross Lillistone’s Phoenix III design, keep in mind I am sailing with only the Alaska mainsail (85 sq ft) and not the ketch mizzen (49 sq ft), so much lower sail area—from what I’ve seen, the boats are not far apart in performance or capability (with the Phoenix III using the 76 sq ft balance lug).

The Alaska probably has a slight edge rowing, especially with two aboard; the Phoenix probably has an edge beating. Available space aboard is remarkably similar—luxurious for one, comfortable for two, starting to feel crowded with more—though Alaska has a marvelous lounging seat up in the bow that the Phoenix lacks.

Alaska seems a bit more tender initially, but hardens up nicely. Freeboard in the Phoenix III seems a bit higher. Alaska is noticeably heavier, so accelerates more slowly. Top end speed: Alaska should have the edge with longer waterline, but in practice they’ve seemed pretty equal so far with one brief trip together.

Both boats are easily recovered—singlehanded—from a capsize. The Alaska is remarkably stable when filled with water—maybe even more stable than she is empty. That alone is a great safety feature.

My conclusion so far: I expected it to be hard for the Alaska to live up to the Phoenix III. So far, though, I am not seeing any deficiencies and they seem to both be great sail-and-oar cruising boats.

I’d be happy to try and answer specific questions if anyone poses them. Thanks!

Love the area and your story Tom! Dianne and I have enjoyed this area very much. We will still visit again, as there is so much to see. One correction the “wave-sculpted granite” of West Fox Island, is in fact sculpted by glacial action, true that flowing water with aggregate under the ice is the culprit. The area is renowned for the beautiful sculpted rock left from the last ice age. At times “kettles” in the granite can be found with the the rock that carved them still in tact at the bottom. This season we managed to pass the narrows of Bear Drop Harbor as per your tale of Jugular Goes Everywhere! A highlight! Keep up the great tales and we will make a point of tailing you at some point!

Roy,

Thanks for chiming in. Bear Drop Harbor is one of the best places in the North Channel. Glad you made it up there.

Thanks for the correction on the glacial vs. wave sculpted rock—though of course, there has been plenty of wave sculpting after the glaciers retreated, eh?

By the way, apparently what you call “kettles,” we call potholes in Wisconsin. I did see a few around Georgian Bay.

Potholes it is, Tom! Upon checking, “kettles” are the larger depressions left by large chunks of glacial ice that are now either small lakes or low, wet depressions. Love chatting with you as I am always learning stuff! Eh! LOL!

Roy, I thought it might be one of those Canadian/European disconnects like “first floor” meaning one thing here, another thing there. But apparently, it’s just that I happened to be right about something!

Roy’s correct that those features are glacially sculpted rock, by sub-glacial water, but they’re different than potholes and kettles.

Potholes are open channel (stream) forms created by swirling eddy currents – you’ll find them below waterfalls and large rapids. They may have some furrowed channels, but they’re typically cylindrical in shape. Taylor’s Falls state park in Minnesota has some gigantic potholes. Watkins Glen in New York has some oft-photographed potholes. Fossil Falls, in California east of the Sierras, has some of the coolest potholes I’ve seen.

Kettles are circular depressions in glacial sediment (not rock). They’re created by the unequal meltout process of thick glacial ice that contains sediment. This is usually translated as depressions left by ice blocks, but that’s a bit of an oversimplification. Kettled topography has a lot of depressions. Kettle lakes are lakes within these depressions. Most lakes in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota are kettle lakes (if they’re roundish, or amoeba shaped, and not in bedrock, they’re probably kettles). Northern Ontario doesn’t have that many kettle lakes, they’re more often depression in bedrock.

High pressure water moving under a glacier can scour channels – which is what Roy’s first post suggested. Kelly’s Island in Ohio is a classic example (Google “Kelly’s Island glacial grooves”). Grooves is a key observation – a channel of water with sediment scoured the rock.

If you think back to wave-dominated, bedrock coastlines – you’ll soon conclude you don’t usually find features like you photographed. The waves will actually destroy those features. The land in Georgian Bay is rising due to the release of weight from the ice sheet melting thousands of years ago, and ‘fresh’ bedrock is being exposed. With time, that cool rock will weather and erode away.

Sorry for the long post – but you two sounded like you were curious.

Thanks for the story! That area is on my life list.

Andy, thanks for your post here. I am indeed curious about all that. I’ve seen the potholes at Taylors Falls; I also found a few similar, but smaller, formations in Georgian Bay, where it looked like a rock had gotten caught in a depression and swirled around via wave action rather than current. They certainly had the typical cylindrical shapes. Am I wrong about to conclude there are lake potholes as well as river potholes?

Thanks for the comments. My Alaska is turning out to be as good as I hoped, and Don was great to work with.

An Ilur would be a perfect boat for a Georgian Bay trip for sure—and I don’t think it’s possible to recommend the Canadian side of Lake Huron highly enough for small-boat cruising. Every year I keep thinking I should get out to the coasts—Maine, the Inside Passage—but it’s hard to make that commitment when there’s something this good so much closer to home.

Great writing and photos. It makes us want to explore the freshwater lakes but it’s hard to leave the saltwater ways of British Columbia in the summer. Maybe some fall!

Great story Tom! Thanks for taking the time to write it. Glad to see the new boat is doing what you expected of it.

Alex, thanks for your comment. You probably know as much as anyone about what an Alaska can do, with all your travels in HORNPIPE. Yep, I’m really happy with the design.

Tom,

Enjoyed the story. I live in Tennessee, have sailed just a wee bit in Owen Sound in the company of other Siren 17′ 2″ Micro-Cruiser owners, haven’t made it to the North Shore yet, but this story is further inclining my heart that way.

Ol Bill

Loved the story, Tom. The Alaska has beautiful lines and looks like she’s flying even at anchor in a mirror-smooth nook somewhere. I especially enjoyed your description of the Northern Lights. Your words are literary artwork. You are a craftsman and put us there with you, in absolute awe. Thank you for sharing all of that with us.

Wayne McCallum

Tom can you tell me how you set up your shock-cord “autopilot”?

Dick Baldwin

Tom wrote about his autopilot in “A Simple Tiller Tender” in the September 2017 issue of Small Boats.