It was a very gentle bump. I’d been sleeping comfortably at anchor after a long day on the water, but I was wide-awake in an instant. A few seconds later it came again—a firm nudge from below interrupting the soft, easy motion of my boat—and this time WAXWING stopped moving. I was aground. I checked my watch—3:30 in the morning, still an hour and a half to go before low tide.

I was quickly out of my sleeping bag and up at the bow, rolling back the boom tent to make room to work. There was no moon out, and in the pitch dark I tentatively stepped out of the boat, probing for the bottom with a bare foot. I slipped up to my thighs into the bracing, 60-degree water and found firm footing on a sandy bottom. With my weight out of WAXWING she floated again, her keel lifting just above the boulder beneath it. A gentle shove freed her and I hopped back aboard. Standing in the bow, I pulled the anchor rode and chain in as quietly as I could and stowed the anchor at my feet.

I reached under the boom tent, fished out one of my oars, and sculled WAXWING in a lazy half circle out to deeper water. The blade slicing through the water stirred up cascades of phosphorescence, which gleamed like fireworks across the inky black water. A dozen yards to starboard, a soft glow penetrated the murk; Rob slid back a corner of his boom tent, and the bright light of his LED lantern appeared. “Everything all right, John?” “No worries,” I called back cheerfully, “We’re just having a little adventure.” When I’m sleeping aboard my boat, being awakened by something that goes bump in the night is never just a good night’s sleep spoiled; it’s an experience.

John Hartmann

John HartmannWAXWING (top) and SLIPPER, loaded with gear prior to departure, wait at the dock in Herrick Bay, pointing southeast toward the islands that separate Blue Hill Bay and Jericho Bay. Summer mornings here are usually calm; winds develop as the day wears on and the sun warms the land enough to generate on onshore breeze.

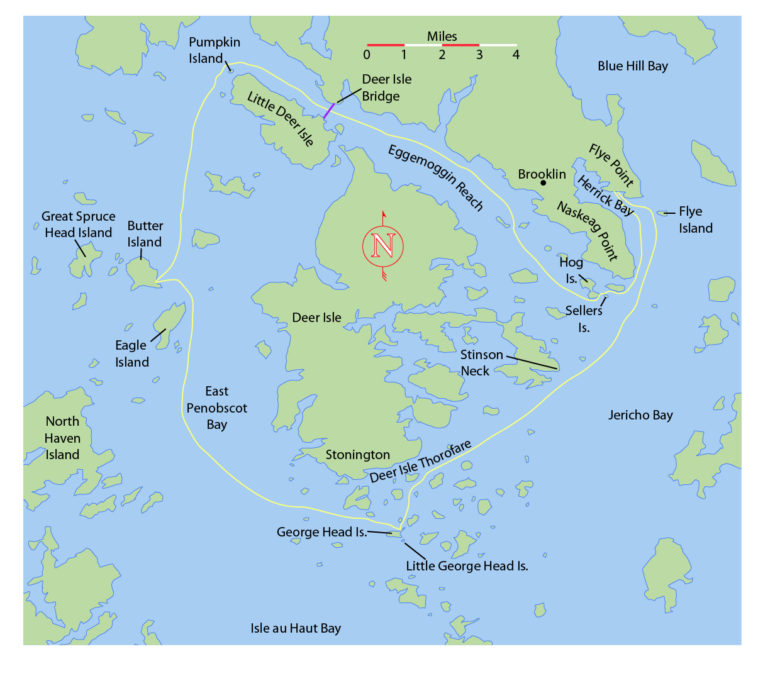

Rob and I had started our adventure on the heels of the Small Reach Regatta, a gathering of mostly wooden, mostly owner-built small boats. The fleet had moored in Herrick Bay, a half-mile wide inlet between Flye Point and Naskeag Point near WoodenBoat’s campus in Brooklin, Maine. After the event, he and I had left our boats anchored there for a day of provisioning. Our plan was to circumnavigate Deer Isle under sail and oars.

John Hartmann

John HartmannThe Ilur has a voluminous cockpit with room enough to carry gear for a multi-day trip. The blue duffel holds a bedroll, the green bucket is for bailing and collecting trash, a clear dry bag holds clothes, and the white bucket is the loo. The gray chests with red lids are kitchen and larder, the yellow soft cooler is ice chest for cold drinks and fresh foods, and the green cooler holds a five-gallon container of drinking water.

When we returned the next morning, Rob made preparations aboard SLIPPER, his 16′8″ Herreshoff Coquina, and I stowed a small mountain of gear in WAXWING, my 14′8″ yawl-rigged, François Vivier-designed Ilur. I made sure everything was secure and out of the way so I could freely move about in the cockpit, and we shoved off by mid-morning.

The tide would be in our favor until late afternoon; the wind, building out of the east, appeared as little cat’s-paws dancing on the water. The breeze swirled toward us across the bay, cooled our sun-warmed faces for a moment, then gamboled away. SLIPPER and WAXWING ghosted along side by side as the dark blue-green water slid lazily past. I got the rig set and shifted my weight to leeward to settle the boat over on its bilge to reduce the hull’s wetted surface and eke out a little more speed. Weaving among and around floating mats and broad bands of bronze-colored seaweed, we stayed well off Flye Point, where I could see, even now just past high tide, the telltale curdling of water washing over the barely submerged mile-long boulder field strewn between the point and Flye Island.

We were covering ground slowly—little more than 1 mph according to my GPS. At this speed, we would likely make it only as far as the east end of the Deer Isle Thorofare before the tides turned against us. Breaking out the oars, I began rowing gently while WAXWING’s big, fully battened, standing-lug mainsail took advantage of the bit of wind we had. With the tide coaxing us along, the combination of sailing and rowing nudged our speed up to almost 3 1/2 mph.

Off the Naskeag Point side of Herrick Bay, a broad-winged osprey vaulted from the top of a tall spruce, sailed out over the water, and pulled up momentarily to hover, eyeing the water before winging away. Rob and I row-sailed for a bit; the wind finally freshened and we shipped our oars.

John Hartmann

John HartmannAs Rob passed the ISAAC H. EVANS in the Deer Isle Thorofare, the schooner was sailing against the tide and getting a motor assist from the yawl boat astern. Built in 1886 for harvesting oysters along the coast of New Jersey, she now works out of Rockland, Maine, and sails the coast as part of the Maine Windjammer fleet.

By noon, we’d crossed the southern end of the Eggemoggin Reach, and rounded Stinson Neck, the southeastern tip of Deer Isle. Our course turned from due south toward southwest as Deer Isle Thorofare opened ahead of us; tide and wind now swept us along as the miles unfolded. From this vantage point, the shoreline of Deer Isle at the eastern end of the Thorofare is corrugated with peninsulas and islets. A sprawling archipelago of small islands between Deer Isle and Isle au Haut studded the steely blue waters as far as we could see.

The Thorofare is a very busy waterway along the southern coast of Deer Isle. As Rob and I sailed along, a group of five large schooners was heading up the passage together, working against the tide with sails set and yawlboats nudging them along. Toward the western end of the Thorofare, we ducked out of the main passage and headed south again, threading our way through numerous islets, nameless shoals, and sand bars on the way to George Head Island, an uninhabited islet scarcely a third of a mile long set in the heart of the archipelago.

John Hartmann

John HartmannThe cove at George Head Island provides a protected anchorage until the tide covers the sand spit leading off to the left to Little George Head Island. Merchant Island and Isle au Haut Bay lie in the distance to the south.

We slipped into the cove on the east end of George Head in late afternoon, a short while before the low tide. A large sandbar extends from the northeast corner of the island, and another curves out from the southeast corner to reach its smaller sibling, Little George Head Island. The bars form a well-protected cove at all but high tide. Now, nearing low slack, both islands were fringed with a broad band of exposed, weed-covered cobble and boulders. In the shelter of the cove, the scent of the exposed intertidal was pungent but pleasant.

We would be sleeping aboard our boats, and with overnight winds expected from the southwest, we decided to anchor on the Stonington side of the northernmost bar, to be in the lee of George Head’s densely wooded eastern shore. By the time Rob and I had set our anchors for the night, it was not long past low tide, so I let out enough extra rode to have adequate scope for the midnight high. As we slept the wind and tide nudged WAXWING over a large boulder in the small hours of the morning, and the rippled sea and ebbing tide soon had it bumping against her hull.

John Hartmann

John HartmannWith the boom tent up and after thwart stowed, WAXWING is ready for the night. The boom tent is a minimalist affair, very wind- and rain-resistant, but open at its ends. If protection from insects is needed, a 4’ x 6’ foot piece of no-see-um netting draped over the sleeper’s head is put to use.

Once WAXWING was safely anchored in deeper water, I settled down to try to get another hour or two of sleep, but it was nearly 4 a.m., and the fleet of lobsterboats that operates out of Stonington hustled toward the 50-yard-wide channel between the George Head bar and St. Helena Island. I could hear the roar of the big diesel engines even as the boats powered out of Stonington Harbor, and the din reverberated through the cluster of small rocky islands around us. The fleet approached and funneled through the gap only a couple of hundred yards from us. After the first few thundered past, I gave up on the idea of any more shuteye, and stowed my bedroll just as day was beginning to break.

John Hartmann

John HartmannWhile SLIPPER and WAXWING were rafted up for breakfast, the low tide uncovered the boulder garden on the north side of George Head Island. One of the boulders in the area knocked against WAXWING’s bottom in the middle of the night, requiring a bit of wading to get her over deep water.

Rob was up too, so I hauled anchor, sculled over to his boat, and rafted up for breakfast. I dug out my old brass Svea stove, an ancient and trustworthy traveling companion, along with my Bialetti espresso pot. The yellow flames from the fuel I’d dribbled into the primer hollow at the base of the stove flickered up and before long the little stove’s blue flame was making a roar of its own, Lilliputian compared to the big lobsterboats, but much more welcome. Breakfast was homemade granola, fresh Maine blueberries, and a piping-hot latte. Although Rob tends toward minimalist camping and frugal dining, no doubt habits fostered by years of sea kayaking, I sail a type of boat that was once meant to carry fishermen and a boat full of fish safely back to port every night. She is a weatherly little packhorse, and I happily take advantage of her capacity, routinely stuffing her with provisions enough to take care of three or four sailors on outings of as many days. Rob cheerfully tolerates my sybaritic tendencies, and made no objection to the foamed latte as I handed it across.

WAXWING and SLIPPER bobbed gently in the cove as the rising sun sent spears of gold up through breaks in the clouds. The water was glassy calm, and the dawn reflected in a great shimmering column of light. I was sleep-deprived and salt-crusted, but this was still heaven on earth. Arctic terns cried, wheeled, hovered, and dove along the bar. One hungry bird splashed down less than a dozen feet from us, then surfaced and wheeled away with a wriggling 3″ sand eel dangling from its orange beak.

Sipping our coffee, we listened to the weather forecast, looked over our charts, and considered the tides as we discussed the day ahead. We’d have light and variable morning winds, and afternoon winds to 10 mph. Low tide was fast approaching; our intended destination would be Butter Island, 11 miles up East Penobscot Bay. If we waited till midday, there would be wind for reaching, but we’d also lose a favorable tide, and progress would be iffy. We separated the boats, Rob weighed anchor, and we set out rowing north-northwest.

East Penobscot Bay was dead calm, disturbed only by the eddies swirling off the tips of our oars. Striking out into the wider waters between Deer Isle and North Haven Island, we made our course toward Eagle, Butter, and Great Spruce Head, a trio of mile-long islands in the middle of a cluster of smaller islands near the top of the bay. It was still early, and except for a few lobsterboats rumbling off in the distance, we had the eastern bay to ourselves.

After a bit of rowing, Rob and I were well offshore, but not entirely alone. A succession of seals followed us for about a minute at a time, staying 20 or 30 yards off our sterns, with their great, dark eyes fixed on us.

John Hartmann

John HartmannFor the long row north to Eagle Island, Penobscot Bay was glassy calm.

Rob and I took a break, put on sunscreen, and snacked on granola bars and fruit. The tide carried us up the Bay and past the tip of Eagle Island. The water was glassy smooth from Deer Isle 2-1/2 miles to the northeast, the same distance to North Haven in the southwest. Over WAXWING’s transom, the sky met the open Atlantic beyond Isle au Haut Bay. We took to the oars again, pulled for Butter Island, and by late morning came ashore on the broad crescent of Nubble Beach on its eastern shore just before high tide.

We had the whole afternoon ahead of us, so we put the boats at anchor to keep them afloat through the falling tide cycle, and set off to explore the island. It is a mile long and a half mile wide, its shoreline scalloped with beaches. We walked a trail through shaded woods to the 150′-high summit of Montserrat Hill, where we could see the upper end of Eggemoggin Reach 7 miles to the north, and the undulating ridgeline of the Camden Hills 15 miles to the west across West Penobscot Bay. There is a polished granite bench at the summit, a memorial to Thomas Cabot who bought Butter Island in the 1940s to preserve it for the people of Maine. Engraved on its thick curved edge is a line for Tennyson’s poem “Ulysses”: “Come, my friends, ‘tis not too late to seek a newer world.” From the bench we had a clear view down to the beach, where SLIPPER and WAXWING were riding quietly at their shared mooring, with plenty of water beneath them in the receding tide. A schooner worked its way up the East Penobscot Bay, and thunderheads piled up over the mainland.

John Hartmann

John HartmannThe view from Montserrat Hill took in WAXWING and SLIPPER anchored next to The Nubble, a rock outcropping at the easternmost point of Butter Island. Tides are commonly 10′ to 12′ along this part of the Maine coast. The boats are on a modified Pythagorean mooring to keep them afloat and off the beach, but easily retrievable.

We made our way back to the beach; it had been a full day, and we turned in after an early supper for a sound sleep anchored off Nubble Beach.

Following breakfast the next morning, we set out north-northwest, rowing in the calm until we were about halfway between Bradbury and Pickering islands. The waking winds, coming from the southeast, hinted of a useful breeze. Rob and I set our sails to catch whatever breezes might help us, and then got back to rowing to speed us on our way. Not far off, pods of harbor porpoises surfaced, swimming in ever-tightening circles as they corralled small fish for their morning meal. The sound of their quick breaths carried across the water to us in the stillness of the morning.

John Hartmann

John HartmannIn a light breeze Rob row-sailed toward Pumpkin Island and the top of the Eggemoggin Reach. Sail-assisted rowing made it possible to cover mileage more effectively when sail alone would have been too slow to keep the pair on schedule to make good use of the tidal currents around Penobscot Bay.

We rounded Pumpkin Island, a low islet scarcely large than a football field, skirted in bare granite with a squat cylindrical lighthouse attached to the keeper’s house at its center. At the head of Eggemoggin Reach, the winds steadied, so we stowed the oars and sailed southeast down the Reach toward the suspension bridge that links Little Deer Isle to the mainland. The breeze was now coming from the east-southeast, so we had to work to windward. The winds were still light, and the going was slow. I tacked back and forth below the bridge, looking up at the catenary curves of the main cables, the thick green girders beneath the roadway, and the delicate looking web of criss-crossed suspension cables between them. The tide had come to its high slack about the time I passed under the bridge, tacking back and forth between the Deer Isle causeway on one side, and a red nun on the other.

Rob was five or six hundred yards ahead of me in SLIPPER, and all of a sudden he was away like a rabbit, coursing down the Reach carried by an ebb tide flowing south to Jericho Bay. It dawned on me that where I was sailing the water was flowing north out of the Reach on an outgoing tide. I had not yet passed the tidal watershed! I was barely holding my own, tacking repeatedly from nun to causeway and back again and again. With the wind on my nose, and the strengthening ebb against me, I had no choice but to drop the rig and start rowing—with grim determination. After a half mile the rowing seemed easier, and I could see that the shoreline was slipping by a bit faster. I shipped the oars, hoisted sail, and with more than a little relief I was under way again, now keeping pace with Rob and SLIPPER.

John Hartmann

John HartmannThe Deer Isle bridge, spanning 200’ at a height of 85′ above the water, opened in 1939. It was built to a design similar to Washington’s Tacoma Narrows bridge, which famously collapsed in 1940 due to wind-induced oscillations. The Deer Isle bridge was also damaged by oscillations in strong winds and extensively modified in 1943.

The day was warming up, and the onshore breeze was coming alive; the winds continued to freshen as the afternoon grew hotter. Before long I had to sheet the mizzen in tight, heave to, and tie a reef in the main. Down through the southern end of the Reach, Rob and I had some pretty spirited sailing, and we were both up and down on the rail for the next three or four miles, our two boats punching forward on blue-gray water generously flecked with white caps.

Around the outside of Hog Island at the tip of Naskeag Point, we met the 65′ schooner ISAAC H. EVANS, returning from Mt. Desert Island. With a magnificent spread of canvas driving her, she fairly swept up the Reach, soaring past us with a hiss of water foaming along her sides, a picture of power and grace.

Gabrielle McDermit

Gabrielle McDermitWith three miles left to go, WAXWING stopped at a sheltered beach on Sellers Island.

Soon we were rounding Devils Head at the end of Hog Island, and broad-reaching for Sellers Island, a wooded islet surrounded by boulders on all but its north side. I could see my wife Gabrielle on the beach, waving. She and our young friend Erika had been aboard WAXWING for the Small Reach Regatta earlier in the week, and today had sailed a small pram the half mile from Naskeag Harbor out to Sellers’s semicircle of white sand, hoping to meet up with us as we left the Reach. Seeing Gabrielle waiting for me on the island’s boulder-studded outer shore made me feel like a 19th-century ship captain returning safe from sea after a long voyage.

Rob and I landed on the beach, and after a break to stretch our legs, Gabrielle joined Rob in SLIPPER, Erika hopped aboard WAXWING, and we took the pram in tow. It was early evening, and the onshore breeze was dying away with the setting of the sun. Gabrielle rowed SLIPPER around the point and up Herrick Bay toward the takeout, but there was still enough wind for WAXWING’s large and powerful rig, so Erika and I hoisted sail, and she skippered WAXWING back to the mooring.

We left the boats anchored and would haul them out the next morning. Rob and I paused at the top of the dock looking back at SLIPPER and WAXWING, both riding quietly at anchor in the last light of the day. There was more to Tennyson’s poem than the line inscribed in the bench atop Montserrat Hill on Butter Island. In another passage he expressed the lure that draws me to explore the coast in a small boat and the touch of sadness I feel at the journey’s end:

I am a part of all I’ve met;

Yet all experience is an arch wherethrough

Gleams that untravelled world whose margin fades

For ever and for ever when I move.

How dull it is to pause, to make an end,

To rust unburnished, not to shine in use!![]()

John Hartmann lives in central Vermont. He built his Ilur dinghy, WAXWING, to sail the 1000 Islands region of the St. Lawrence River, Lake Champlain, and along the coast of Maine. He details the Pythagorean mooring system he used at Nubble beach in the Technique article in this issue.

Good writing! Please write more.

Ah, just now I was right there with you! A joy to read.

Please do look up the Ottawa Small Boat Messabout gang if you are ever inclined to share the Thousand Islands with a small fleet of like-minded enthusiasts who would love to see your wonderful boat up close.

What a delight to read John’s account of our little expedition! This was a trip I had thought about taking for years, ever since I read Joel White’s description of sailing around Deer Isle in his Herreshoff 12 1/2 when he was a kid. When John mentioned that he’d like to make the trip as soon as the Small Reach Regatta was done I eagerly signed on. We probably covered more distance under oars than sailing, but both SLIPPER and WAXWING are well designed to be satisfying in either mode of travel. For the record, SLIPPER is a copy of Nat Herreshoff’s Coquina. She is 16′ 8″ long and 5′ beam. Thanks, John, for taking the time to write up our adventure!

Yeah! I own an Ilur too—one of my most favorite small wooden boats designed by François Vivier. Always love to see others Ilurs. Thank you for sharing this thread.