After many years of sailing fiberglass boats, the thought of giving trees a new life in the form of a planked hull inspired me to build a wooden boat, one that would put me through the challenges of building in the traditional manner. It had to fit in my shed, and be trailerable and not too big for me to handle on my own yet still stout enough to bump off the occasional rocky shore. The workshop I had access to was limited in space—a 16-footer wouldn’t fit—so a 12-footer it was going to be.

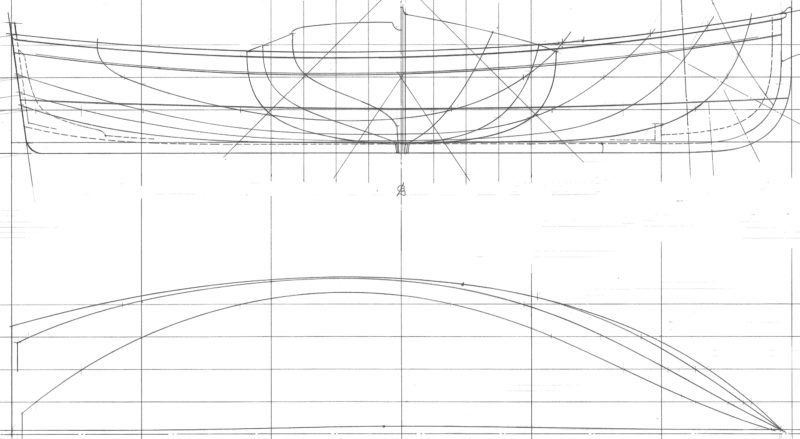

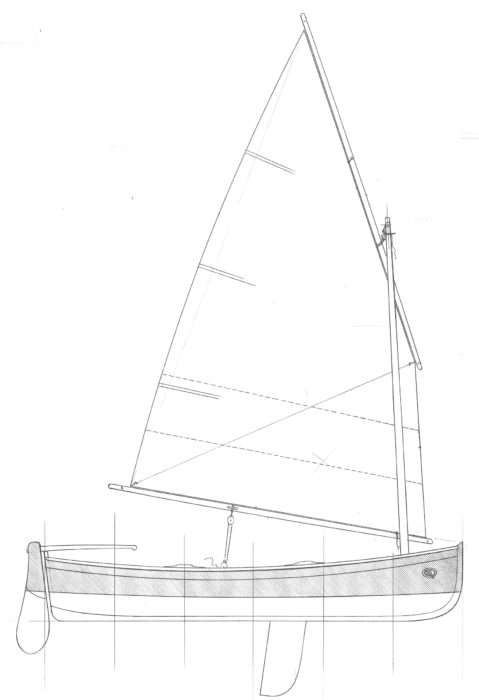

My search on the web led me to Paul Gartside’s boats, and I quickly zoomed in on his 12′ Clinker Dinghy, Design #130, drawn for the Silva Bay Shipyard School in Gabriola, British Columbia, as an exercise in lapstrake planking. Its lines were inspiring and sweet and convinced me to buy the plans. The six pages of plans, available in hard and soft copy, include lines drawings with keel and stem details, offsets, construction drawings with scantlings and fastenings, stem lofting, construction details, and a sail plan. The skill level for building the boat, as indicated on the Gartside website, was “high,” but the plans were so detailed I wasn’t too worried. They proved to be perfect, with all the detail needed for the build, though the project requires good technical skills of both mind and hands. Whenever I had questions, advice was always available from Paul.

I had no previous boatbuilding experience, but, confident in my woodworking skills, I set to work. The lofting took six weeks and a sore back. The offsets were accurate and needed no corrections. I made the five molds from pine, sabersawed to shape.

Where possible I followed the plans’ timber recommendations, but local availability often dictated what I could use. Paul confirmed that my substitutions were acceptable but advised using his recommendations for the structural and load-bearing parts.

Photographs by Dick Bedell

Photographs by Dick BedellDesigned as an exercise in traditional lapstrake construction, the 12′ Dinghy isn’t going to be a quick build, but the richly detailed interior will never lose its appeal.

For the keel and deadwood, I used Douglas-fir as recommended. Red cedar was indicated for the planking, but I decided on mahogany for the first nine strakes—it was in good supply—with a Sitka spruce sheerstrake for contrast. The swirling grain of the mahogany tended to tear out when planing, but in the finished boat it would be tougher and will not bruise like red cedar or spruce. The thwart knees, quarter knees, and breasthook are called out in the plans as oak crooks or laminations. I laminated mine: mahogany for the thwart knees and oak for the others. The frames are steam-bent oak, 3/4″ x 7/16″ on 5-1/2″ centers, and copper-riveted. The remaining structural parts—mast bench, and ribs—were made from oak. The thwarts are specified as red cedar; I used mahogany. The 5/16″ red-cedar floorboards (mine are yellow pine) are made in removable panels. I made the transom from 1″x9″ tongue-and-groove mahogany in lieu of the splined oak called for.

While the stem, as drawn, is three pieces of oak, fastened with copper rod and calls for a grown knee, I made mine from 26 laminates of 4mm mahogany. After I initially tried to epoxy the whole 26 layers of 4mm mahogany for the stem in one go, and realized it was a mistake, Paul suggested gluing up batches of eight laminates. I had initially steamed the laminates to bend them over the form in small batches when they were dry and I tried to glue them together. My shop-made jig was deflecting and my clamps did not have the power to pull the laminates into shape. I laminated them with epoxy, successfully, in batches of eight.

The span at the locks of the aft rowing station will take a pair of 9′ oars, long enough to provide the boat with ample rowing power.

The transom and stem get pinned to the keel with 3/16″ copper rod peened over bronze washers. When the backbone is complete it is set right-side up on an elevated beam, and the five molds are braced over it, spaced 24” apart. There is a note on the plan for setting the molds on a ladder frame for building the hull upside down.

I bought mahogany for the planking in 15′ lengths of 9″ x 3/8″ stock. Trying to shape, fit, and rivet the garboards to the apron was difficult for me working alone, especially building the boat right way up and trying to keep the bucking iron flat against the rivet head while peening the other end. The first few strakes needed steaming to facilitate the twist for the planks’ forward ends to meet the stem rabbet.

Two options are offered for the gunwale: an inwale and outwale sandwiching the sheer planks and frame heads (my choice), and a single-piece gunwale, placed flat and steam-bent, and screwed inside the sheer planks above cut-down frame heads. The latter leaves the top of the sheerstrake unprotected, but includes an oak rubrail beneath it.

The dinghy trims nicely with the rower at the forward station and a passenger in the stern.

I made the mast, boom, and yard—all tapered and rounded—of pine. The balanced lug sail has a battened leech and two reefs. In correspondence from Paul, he mentioned that the sailing rig was a later addition to the design. The daggerboard now included in the plans is glued up from sections of vertical grain Douglas-fir and its trunk is braced by a 4-1/4″-wide piece of oak that connects it to the thwarts. Paul also recently noted: “If used as a sailing dinghy, it would be better with a pivoting centerboard rather than the daggerboard shown—daggerboards are not the easiest things to live with.”

After 22 months and 1,800 copper nails, my Clinker Dinghy, christened MAGGIE MAY, was finished and ready to be launched in the local canal. The unstayed mast and the balanced lug rig are very easy to set up, and it takes just 20 minutes to get ready to sail. The dinghy proved easy to launch by floating on and off the trailer on the slipway.

The boat has good stability and builds confidence. It makes a very good fly-fishing platform. The sternsheets and thwarts are more than enough for the crew with plenty of room to stretch your legs. The dinghy has a second rowing station for balancing the boat when taking a passenger in the sternsheets. I’ve rowed on lakes with good control and maneuverability, and the dinghy glides gracefully along with a whisper—a pleasant experience. Although they’re not in the plans, I’ll add foot braces for more powerful rowing. On a day with a wind at Force 2 to 3, I rowed out of harbor with the wind on the nose and surrounded by rocks. The boat plowed through a wave about 3′ high, which didn’t bother it at all—its weight ensures it can take a wave with ease and not lose a lot of speed—and the two of us on board remained dry.

The balanced lugsail has an area of 68 sq ft.

Performance under sail is excellent downwind, even in light airs. To weather, the dinghy will sail closehauled at about 45 degrees to the wind. It carries no weather helm and the rudder response is excellent, turning on an English sixpence.

While the use of an outboard motor is not noted in the plans, I fitted a transom bracket to port of the rudder for a short-shaft 2-hp, four-stroke outboard. It proved adequate to push it along, although extra crew or ballast is required to keep the bow down. Having the outboard along is comforting when I’m sailing offshore.

The sailing rig is well balanced, requiring only a light touch on the tiller.

Building the Clinker Dinghy was a little daunting at first and I wondered if I’d taken on more than I could chew, but I persevered and got the needed boost when the boat began to take shape and passers-by would remark on how good it looked. Ultimately, it was a satisfying build. While the skill set required is medium to high, the plans are easy to follow and well laid out with clear, instructive details—and under way, the dinghy just as satisfying and very relaxing. What better way is there to spend your time?![]()

Patrick McGowan is retired and lives in Manchester, England. Most of his sailing with MAGGIE MAY is done on the Cumbrian lakes, with occasional trips out to sea along the Welsh coast.

12′ Clinker Dinghy Particulars

[table]

Length/12′ 0″

Beam/4′ 10″

Depth amidships/1′ 5″

Weight/180 lbs

Sail area/68 sq ft

[/table]

Plans for the 12’ Clinker Dinghy, Design #130, are available from Paul Gartside, Boatbuilder and Designer, $135 USD, for either digital delivery or print and ship.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Very nice, salty craft! What a great reward for your labors.

Good article, Patrick. I only lofted on the floor once, never since.

Well done, Patrick. I applaud you for going the traditional route. I myself built design No. 130 in 2007 in mid Wales, but as it was going to live on a trailer, I decided to do so in glued clinker (lapstrake) plywood. Paul forgave me at the time!

It really is a lovely design, at home on the English Lakes or Welsh coast where I also do my sailing. The design really deserves an evocative name to match its sweet curves.

Interestingly Sailrite, when I ordered a new main for my Gartside 130, said that the sail plan is actually 74 sq ft. I really enjoy mine, a student-built boat from the Silva Bay Boat school on Gabriola Island, BC, Canada.