August is blackberry season here in the Pacific Northwest, and in Seattle the best picking is at the water’s edge where the brambles are accessible only by boat and almost always untouched. Picking blackberries with my daughter, Alison, is a tradition that has a long history. In mid-August of 1993, the day after she was born, we took her out in the gunning dory to pick berries on the brambled shores of Seattle’s Lake Union. This past August, when she flew up from San Francisco for her birthday, she and I planned to go boating together.

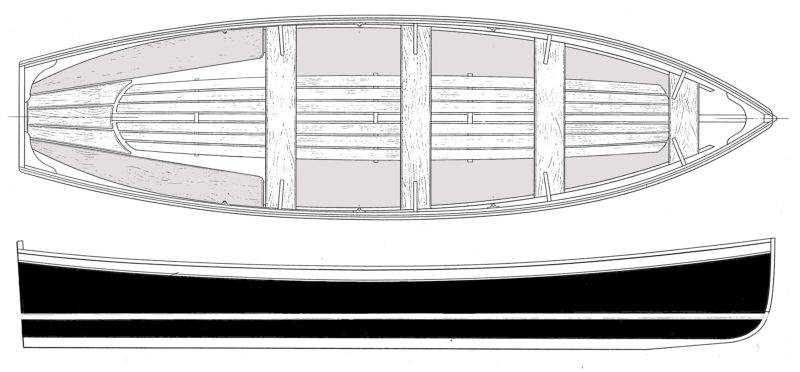

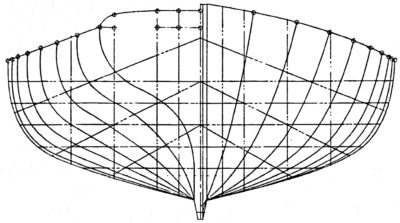

The gunning dory she’d been aboard as a newborn has been idle and without a trailer, so I pulled the Whitehall out of the garage. The best berry picking would not be on Lake Union but on the Sammamish Slough where the banks 1-1/2 miles upstream from the launch ramp were thick with brambles. Our time was limited, and rowing would take too long, so I did something I’d never imagined I’d do: I put an outboard motor on the Whitehall.

In 1978, when I started building boats, and in the years that followed, my interest was only in boats that I could paddle, row, or sail. I began a series of lengthy small-boat cruises in 1980 and took inordinate pride in the thousands of miles I covered under my own steam or by sail. Outboards then were oil-burning two-strokes and I took offense at the noise they made and the rank, blue cloud they trailed. In 1983, as I was putting the last coat of varnish on the Whitehall, if I had foreseen that I would one day willingly clamp an outboard on its beautiful mahogany transom, I could only have imagined that when I reached my late 60s I’d be well over the hill and descending into madness.

Alison Cunningham

Alison CunninghamA pair of gaffer-tape-covered plywood pads, one on each side of the transom, protected it from the outboard’s mounting bracket and clamp screws, but the Whitehall wasn’t content with 40 lbs hanging on its stern. With my homemade tiller extension, meant for another boat, I couldn’t get my weight far enough forward to put the bow down where it belonged.

Ali and I launched the Whitehall at the ramp near the mouth of the Sammamish Slough. I clamped my 2.5-hp Yamaha, a four-stroke, on the transom and we motored upstream. Even at less than half throttle, the Whitehall made good speed, much better than we could ever muster by rowing, but the hull didn’t take well to it. The full middle and the tucked-up stern heaved up a very lumpy wave train.

We made good time along the slough even with the motor at about 1/3 throttle. The transom is well braced with knees, but I didn’t want to strain the boat by applying full power.

We were soon through the gentle meanders where the slough is hemmed in by houses and lawns, docks and boats, and arrived at the bramble-lined stretch that runs straight for a ¼ mile through a city park. I nosed the bow into the south-facing bank where the blackberries are the ripest.

This stretch of the slough was once surrounded by a golf course; it’s now a public park. The brambles occupy the banks on both sides and there are plenty of blackberries.

The blackberries grow right down to the water’s edge. When I kayak the slough, I stop occasionally to pick berries for a little boost of energy. It can be tricky picking from the kayak: the brambles push the kayak away while I push in with the paddle in one hand and pick with the other, usually getting my sleeve snagged on the thorns.

Ali picked this section of the brambles and collected about two cups of blackberries without losing her balance or getting snagged by thorns.

A pint of berries takes only a couple of minutes to pick and less time to eat. In a typical outing we usually pick enough blackberries for two or three pies.

With the midday sun shining on the brambles, every gem-like bead making up each blackberry reflected a bright white pinpoint of light. The ripe berries parted from their stems at a touch while the ripest dropped when the cane they hung from was jostled. Eaten straightaway, the berries we gathered were sweet, soft, and warm. Ali picked until the tips of her fingers turned mimeograph purple. After we had eaten our fill, I paddled the Whitehall away from the brambles to midstream.

Artwork by Alison Cunningham

Artwork by Alison CunninghamWhen a bit of a breeze stirred over the slough, I killed the motor and Ali raised the spinnaker. Although we didn’t sail for long, it was a moment more worthy of preserving than motoring was. I asked Ali to do this rendering of one of the photos I took. When she was very young, she, her brother, my sister, and I often had “drawing contests” and shared doodles and sketches of things we had challenged each other to draw. Ali had a knack for it and has had an interest in art for most of her life. Working with a computer, she has been doing portraits on commission for several years.

A breeze that had slipped between the banks and skimmed the river turned the water the color of blue-tempered steel. I had Ali raise the spinnaker, not because it would take us anywhere we needed to go, but to enjoy the Whitehall making speed as it was meant to, with only the sound of water curdling across the plank laps. When the air grew still and the spinnaker fell and draped itself around its mast, like a flag in an auditorium, Ali dropped the sailing rig and we motored back to the ramp.

We usually pick enough berries to bake pies—that was the purpose of the picking expedition on the day after she was born and for many of the outings we took as she grew up—but on this trip we came back empty-handed. The harvest that really mattered was the time spent with my daughter.

Taking Ali out boating while her age was still measured in hours rather than days and putting an outboard on a boat that was never meant to have one are both what I once would have considered madness, but it’s a pleasant madness, as sweet as sun-warmed blackberries picked in the middle of August. ![]()