Ernest Pattillo was born into a corn-milling family in Tallassee, Alabama, about 30 or so miles from Montgomery, the state capital. The mill and the creek running by it offered everything a boy could want: scrap lumber, nails, hammers, and saws; turtles, catfish, and swimming.

In the mid-1950s, when Ernest was 10 years old, he and his cousin Alton, mindful of summer’s passing, wanted to do something exciting before school started. The creek suggested a boat, and the cast-offs littering the mill suggested building one. They started with a bent and rusted sheet of corrugated metal roofing and a 2×4 bristling with old nails. The boys pulled nails and sawed off two lengths of 2×4 for stems. After they folded the ends of the roofing around the stems and nailed them home, they applied tar to seal the gaps there and the buckshot holes everywhere else. The canoe was only 5′ long and could only hold one of them, so they built a second.

When the cousins got their canoes to the creek, they quickly realized they would have to scale back their dreams for the first expedition. The canoes were unstable and had barely an inch of freeboard. They only had their hands for paddling and had to reach carefully over the sharp edges of the roofing to keep from cutting their armpits. Ernest and Alton used the canoes until their youthful enthusiasm took them in other directions.

Roughly 37 years went by before Ernest seriously considered building another boat. An article by Mac McCarthy in the May/June 1991 issue of WoodenBoat was an illustrated guide to the construction of a strip-built version of Henry Rushton’s Wee Lassie double-paddle canoe. The article included Rushton’s lines for a 10′ 5-3/4″ by 27″ canoe. The drawings on the magazine page were small and without offsets but they were enough to inspire Ernest to take measurements from the picture and stretch the canoe to build a 12′ version.

Ernest stripped his Wee Lassie with fir, gave it a sturdy sheathing of fiberglass, and wound up with a canoe that looked good but was “heavy as lead.” When he launched it for the first time, he got aboard gingerly and was surprised and alarmed when his wife-to-be, Megan, “plopped herself in right behind me. That scared me, as I had no idea if it would even float, much less carry two. But it did, and we paddled upriver and down on the Coosa River, right here in central Alabama.”

Ernest never grew to feel at ease in the canoe, even though it was a significant improvement on his first canoe with its nonexistent freeboard and sharp, rusty gunwale. He put it up for sale and it went quickly.

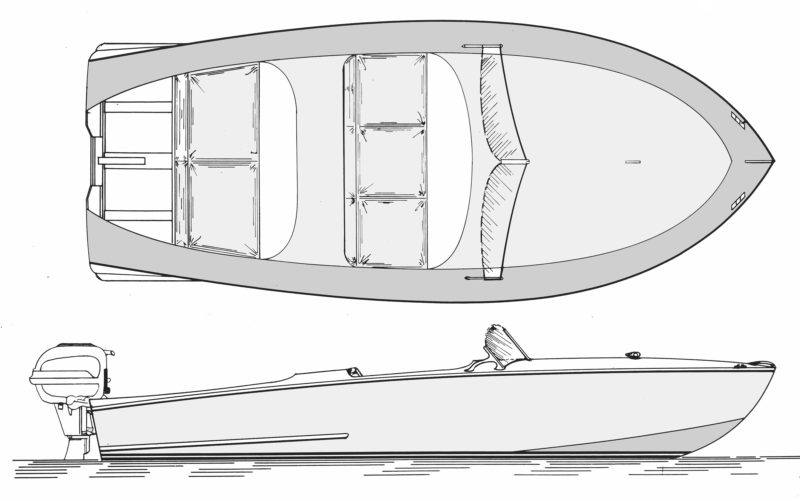

Ernest and Megan eventually married, settled down, and before long the urge to build another boat struck again. Ernest thought his son from his first marriage might enjoy having a boat for fishing. He read up on marine design, “understood some of it,” and drew up a 12′ flat-bottomed plywood skiff. It looked good, kept the water out, and made good speed with an electric trolling motor. His son was pleased to have it but had no place to store it out of the weather. The boat moldered away. “Sometimes,” Ernest sighed, “all the work in the world seems to be for naught.”

His fourth boat fared better, though it might not truly qualify as a boat because it never got wet. A wealthy stockbroker had heard that Ernest had built a canoe and commissioned him to build one to keep at his lakeside cabin. Ernest studied Mac McCarthy’s book to expand his strip-building knowledge and put his best work into the canoe. When the customer picked it up, he was delighted with the beautiful colors of the western red cedar strips, the mahogany sheer, and the woven cane seat. A few weeks later, he sent a picture to Ernest, showing the canoe, forever high and dry, hanging upside down from the 30′-high living room ceiling of his “cabin” mansion.

Ernest’s fifth boat was another flat-bottomed fishing boat of his own design. It was a 15-footer for a 25-hp outboard. He built the boat to last: 1/2″ plywood on oak frames, fiberglassed inside and out, and painted with baby-blue epoxy paint. It looked great and would last for decades, even if left out in the weather. After launching it, Ernest went fishing a few times and decided to build casting decks for it. Before he finished the decks and had a chance to install them, a storm rushed through and blew a neighbor’s towering pine tree down. It fell across the fence and smashed across the boat from gunwale to gunwale. “It was ruined. I gave it away. I guess it could be made to still float, but I was practically in tears when they hauled it away. And it really killed me when the guy just dragged it on the concrete driveway as he was loading it.”

Photographs by and courtesy of Ernest Pattillo

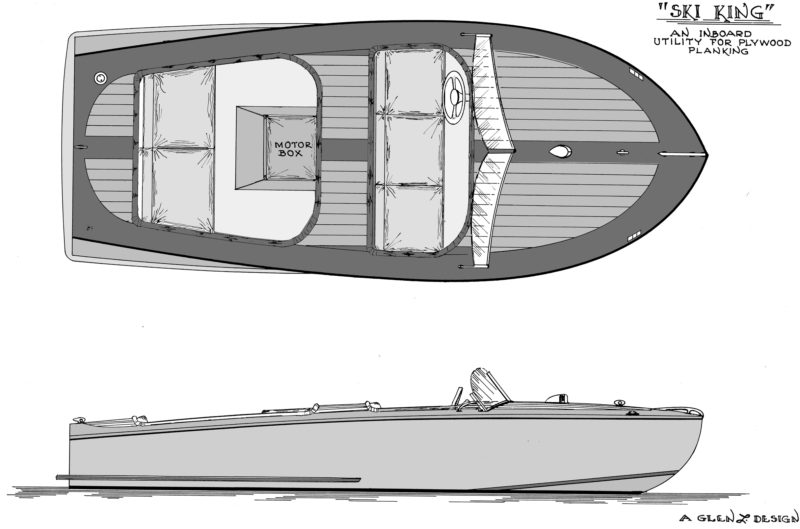

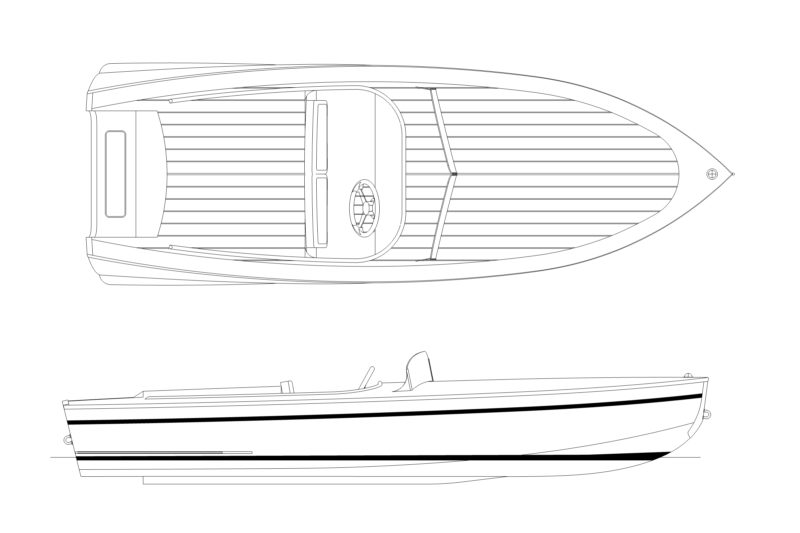

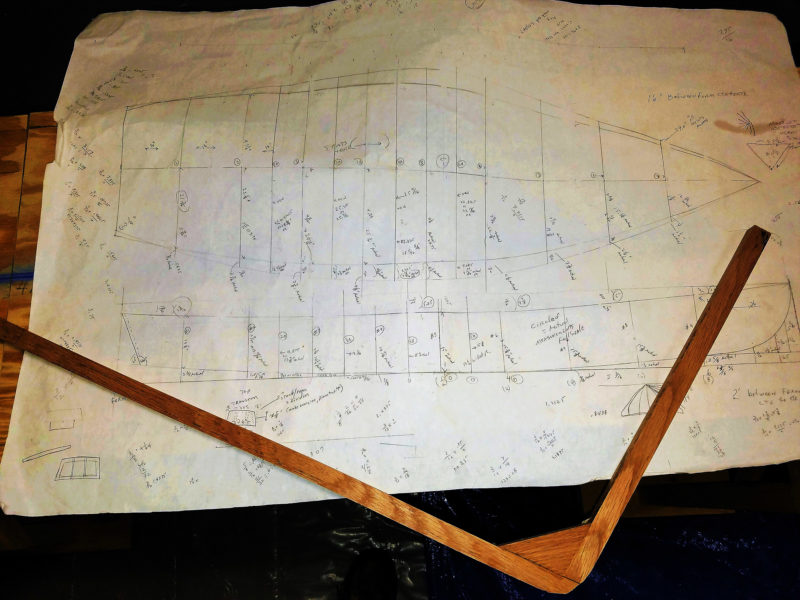

Photographs by and courtesy of Ernest PattilloErnest drew his runabout as a scale drawing and took careful measurements to scale up to the 14′ boat. A bit of tumblehome at the stern would provide a distinctive touch.

Ernest says that his sixth boat, a 14′ inboard electric cruiser, was his last. He drew a rough plan for a flat-bottomed boat with flat, nearly plumb sides, and tightly radiused chines. He set up closely spaced 3/4″×1″ white-oak frames, half-lapped at the chines, and prepared for strip planking.

The white-oak frames were supported by 2×2s screwed to the strongback.

He could get cypress for the 1/4″-thick strips from a bandsaw mill not far from his home. He did the bead-and-cove milling on the strips himself and set up a low-angle sanding jig on his standing belt sander to cut the scarfs. After ’glassing and painting the finished hull’s exterior, Ernest flipped the boat right-side up and outfitted the boat with bow and stern decks, bass-boat seats, and a trolling motor.

The cypress strips were light and easily worked. The flat sides and bottom might have been more quickly worked with plywood—yet boatbuilding is not always a means to an end, but often so pleasing a way to spend time that there’s no need to take the shortest path to finishing.

With the strip-planking finished, Ernest applied some fairing compound, a keel, and fiberglass sheathing.

With the exterior painted, the hull could be righted and set outside for a good view before work on the interior began.

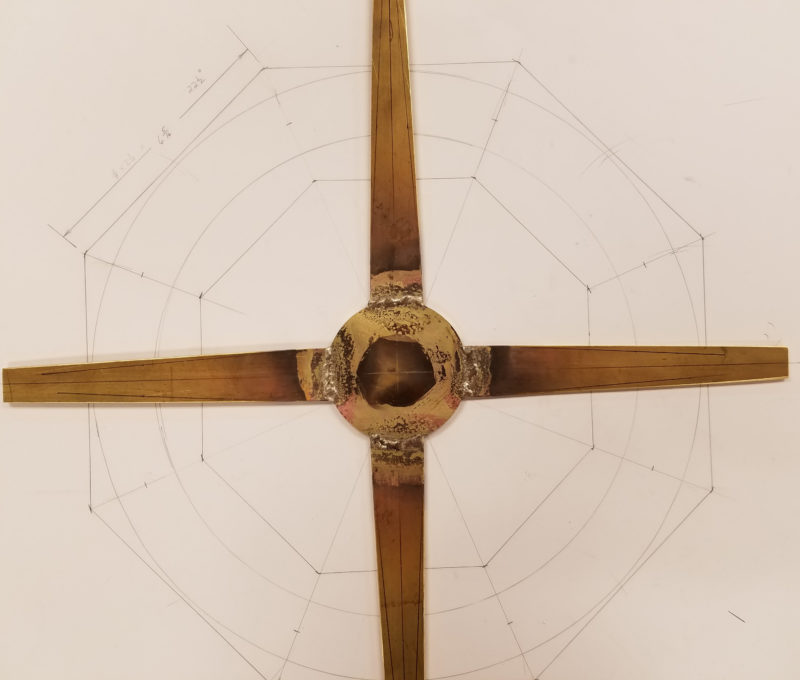

Rather than clamp the motor on the transom, he removed the telescoping motor control from the shaft and installed the motor beneath the hull. The twist-grip throttle went forward and to the right of the starboard seat. A mahogany wheel is connected by cables to a tiller on the motor shaft.

Ernest used mahogany for the decks and the inwales. The port inwale lies in the boat ready to be set in the notches at the tops of the frames. He was “really pleased not only with their appearance but the strength the inwales added.” In the stern, visible between the seat backs as a black upright, is a tube sized to fit the trolling motor shaft. It’s welded to a steel plate that’s bolted to several frames. Several O-rings keep the water out, and the top of the tube is well above the waterline.

With the interior only partially complete, Ernest and his friend Jon took the boat out for an early sea trial. There would be an insulated box between the seats for cold drinks, and the trolling motor’s shaft has not yet been cut to its finished length.

Ernest and Megan enjoyed a brief outing on the boat’s first time afloat. The transom is adorned with MEGOLA, a pet name he has for Megan.

With MEGOLA finally finished, Ernest took his grandkids out for a ride.

The boat was christened MEGOLA, one of Ernest’s pet names for Megan. The two of them have enjoyed the boat, and it has been popular with their friends and grandchildren. But now, at 78, Ernest says, “I’m getting a little old to get in and out of it.” When MEGOLA goes to someone else, Ernest will be without a boat. But all of his work will not be for naught. Every boat he ever built will always be his wherever it is and, with the memories he created along with them, Ernest will never be boatless.![]()

Do you have a boat with an interesting story? Please email us. We’d like to hear about it and share it with other Small Boats Magazine readers.