"Come TINTIN, come,” my four-year-old daughter hollered, then broke into a giggle. Her two-year-old brother threw back his head and let rip with his best belly laugh. We paddled, a family of four snug in a fully loaded 17′ canoe, up Lobster Stream in northern Maine. Tall conifers lined the banks on either side and funneled a mild headwind against our bow. Tethered to our stern, TINTIN, our 16′ wood-and-canvas canoe also teeming with gear, kept slipping broadside to our progress, creating drag like an anchor. I fiddled with the length of the line to no avail. I had built TINTIN 15 years earlier for a 700-mile paddle adventure across the Northeast. Before marriage and children, that trip had turned canoe and boy into an inseparable duo, but fast-forward to our inaugural and long-anticipated family canoe trip, and TINTIN had been demoted to service as a barge. What better way, I had naïvely thought, to instill a bond between my beloved TINTIN and the next generation than a family adventure— yet, 20 minutes into our first day, the kids were treating TINTIN like a goofy pet.

Donnie Mullen

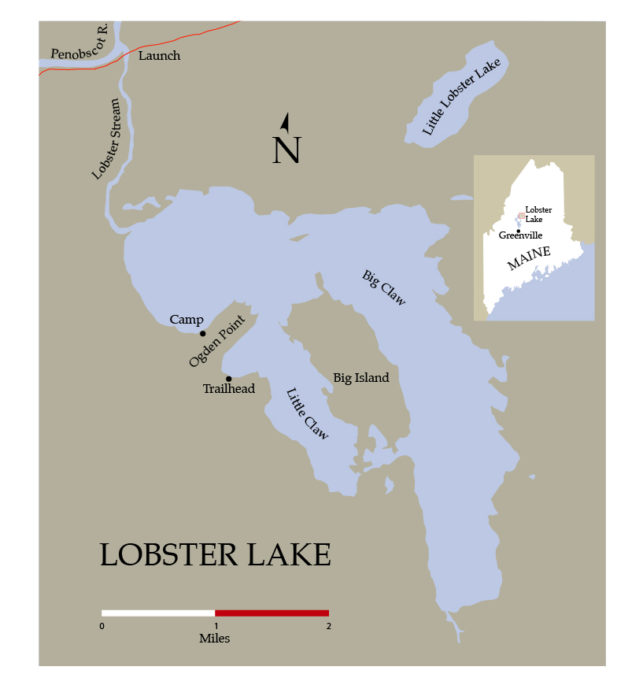

Donnie MullenThe put-in on Lobster Stream is just upstream of its confluence with the West Branch of the Penobscot River. We were all excited, a tad anxious, and already tired following the long journey from home. The 2-mile paddle up to Lobster Lake is, strictly speaking, upstream but in practice it’s an easy flat water trip. TINTIN, in the foreground, carries gear for a family of four.

I was embarrassed to admit that I had stooped to the ignoble act of towing another canoe, but the previous week had been such a chaotic blur that finding the put-in, loading the boats, and shoving off felt like an accomplishment akin to a space-shuttle launch. A month earlier, during a heartfelt and late-night talk with my wife Erin, we agreed that, spring bugs and proper sleep be damned, the children were ready to experience true camping. Erin and I had met while working for Outward Bound and shared a long history of outdoor adventuring, running the gamut from a month-long paddle trip into the wilds of Quebec and Labrador to taking a reflective escape aboard TINTIN on our wedding day. Of course, our late-night declaration required of us a Herculean task: to find, organize, update, and pack the gear required. Then menu planning, shopping, and parceling out the food—which Erin largely executed herself, while also managing the children—as I busied myself with work, a handy camouflage for my being overwhelmed by the complex task of packing for a family of four, one still in diapers. My singular contribution, other than packing my own few clothes, was to mount the two canoes on the roof of our truck in a towering jumble that just might survive Maine’s punishing logging roads.

Erin and I had been to Lobster Lake years earlier, for a single night during a much longer trip, but it had remained in my memory as a tucked-away gem accented by sand beaches, smooth rock ledges, and old-growth pine all resting peacefully below the distant height and length of Mount Katahdin, Maine’s crown peak. The lake seemed like the perfect destination for a family. Our plan: set up camp for four nights and fill our days with short excursions, camp play, and nice meals.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenPrior to the trip, the kids had taste-tested the various snack options and Sumner declared that the sesame sticks tasted like dog food. At Lobster Lake the kids and I came to call them “dog bones” which always elicited giggles but spoiled them for Erin. Sum munched away while Erin held a tarp as a sail.

When we hit the lake, we aimed for the largest beach on the horizon. The wind had picked up, and we decided to lash the boats together as a catamaran. Simultaneously, Erin and I berated the kids for sticking hands in between the gnashing gunwales.

“I’m hungry,” Sumner complained.

Erin wanted to give sailing a try.

“Is it worth the effort?” I grumbled, but what I really thought, a holdover from my Outward Bound days: it’s cheating. Nonetheless, we dug out the tarp—and a snack.

We landed at the beach and it was a hectic moment as we unloaded the kids and the heaviest gear while the boats slopped around in the breaking waves. Standing between the boats, with a hand on either gunwale, a swell sloshed down my left boot. “Already?!” I held back a curse.

Erin tossed the beach toys into the sand. Without delay, Sumner put his front-end loader to work. Ceri lingered, watching us, wanting to help, but I’d told her to stay clear of the commotion. As the gear accumulated on dry ground, she carried or dragged it toward the campsite, at the high end of the beach. Once we had the boats out of the water, and most of the gear up to camp, Ceri joined Sumner at the shore. She tore up and down the beach, gripped by song, jumping, raising her arms and at times, letting her feet flick through the water.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenDuring the trip, we kept a running list of camp items, that—forgotten or overlooked this time around—would enhance subsequent adventures: binoculars, a brush to sweep out the tent, a Dutch oven hook, a small saw, Cholula hot sauce, and better rain jackets. Of course, foremost on our list, added with an eye to improving travel with young children, was a second tent.

In a pleasant cedar grove, I started in on the tent while Erin began to pull out the dinner stuff and erect the kitchen. At one point, we crossed paths and exchanged tired smiles. The kids were playing happily, down below, giving us the freedom to bust through the initial camp setup.

“Wow,” Erin said. “It’s working.”

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenGood food was appreciated by everyone, and definitely helped sell the kids on the trip. Whether it was chocolate-chip pancakes on an overcast morning or Dutch-oven pizza for dinner, mealtime made everyone happy.

After a while, the kids charged up the beach to the camp kitchen, hungry. While they snacked, I noticed that Ceri’s long johns, her only pair, despite being rolled up, were dripping wet. On autopilot, I scolded her and then immediately felt like a heel. Here she was showcasing creative play, that same free spirit, inherited from her mom, which had hooked me all those years ago, and all I could come up with was with a criticism? Oh camping, please settle my nerves.

The onshore breeze was stiff come dinnertime. I slapped up the tarp semi-vertical to try and shield us, but it didn’t accomplish much. We huddled at the picnic table and gobbled. Ceri kept rising, trying to tighten the flapping tarp. The wind stopped at sunset. Then, yikes, mosquitoes. We retreated to the tent.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenCeri, was a perfect age for camping but we could never let Sumner get out of sight. At some times he surprised me with his endurance at sand play and coiling rope, and at others he required constant redirection. He was always hungry and cried if anything other than peanut butter and jelly was served for lunch.

Sumner and I emerged from the tent early the next morning (on his accord, not mine). He beelined to the picnic table and dug out an apple, then dropped it twice in the sand as he walked about. Each time, I washed it clean and requested he sit. Eventually, he did; I wandered off to take pictures. Some minutes later, he called:

“Daddy, come back.”

I returned to find him methodically swatting blackflies. Feeling the absent-minded dad, I quickly helped him to pull on his bug-net shirt, yet he whined when the mesh interrupted his eating. I taught him a skill that Erin had imparted years before on our bug-crazed Labrador trip—lunch inside your bug shirt. He swung his legs gleefully and resumed his eating with his hands and apple safe behind the mesh. Before long, he looked up at me with a mischievous glimmer. “I can’t drop my apple,” he cooed. He promptly slipped off the bench and headed for his toys.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenDespite their goofball sleep-deprived antics, the kids really did play well together. They shared the few toys we carried and collaboratively put to use found material, such as sticks for pre-bed jousting. Okay, it’s a bad example. When they began to incorporate TINTIN into their shared play I imagined a bond forming that would link my youthful spirit to theirs.

We dawdled away the remainder of the morning, while our intent of a proper outing floated like a pillow cloud overhead; camp details descended. Erin and I took turns at the outhouse. Ceri stuck her nose into the woodsy privy and decided in favor of the toddler potty we carried. Then Sumner needed a diaper. Damn, I still hadn’t made coffee. The mosquitoes passed, only to be replaced by horseflies. The kids made a sand-mound village accented with pinecones and sticks. As the day heated up, we peeled off our morning layers, hung our wet clothes out, and applied sunblock. Breakfast dishes were still wet when a peckish Sumner lurked for lunch. After his call went unheeded for too many minutes, he pulled down his diaper.

“LOOK, my bum!” he chortled.

“Christ,” I kvetched to Erin. “Can’t lunch wait?”

Glancing down at the shore, I couldn’t pull my camera out fast enough. Ceri had set her camp chair in the water. Tiny waves lapped at the chair legs while she kicked at the shallows with her boots. The shining blue lake stretched out before her. I loved this about her: her ability to design her own time. At home, she could pour herself into a collage or painting for an hour. Maybe she was just pushing the envelope with the “keep it dry” request, but even so it had flair. This time I was smart enough to praise her initiative when she pranced up from shore.

A while later, Erin tore from the tent, at her wit’s end after an hour of trying to put Sum down for a nap.

“We’re going hiking,” she declared.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenSumner was the wildcard of the trip. He had many moments of happy play and even helped with the dishes a few times, but then he could spiral into unabated silliness. Was he too young for canoe camping? At Outward Bound we often said “Hard isn’t bad. It’s just hard.” And as long as the hard is balanced by a few glorious moments, I can accept it every so often.

We rallied, hastily packed the canoe, put hats on, zipped and clipped PFDs, and grabbed water, snacks, and the child-carrying backpack. Oh, camera bag. And then another jaunt up the beach to find our hiking boots. I ran down to the water, arms full, and we shoved off. To reach the trailhead for Lobster Mountain, a steep wooded face that loomed behind our beach site, we would have to paddle around the ledges of nearby Ogden Point into a neighboring cove.

As we paddled along the shore, we were reminded that without much gear aboard, TINTIN’s initial stability was a tad wobbly. Erin and I said as much, and Ceri latched onto the hint of anxiety. I hoped she wouldn’t notice TINTIN’s other curiosities: extremities that still leaked even after being recanvased, and the hull bumps from old collisions that never quite got replanked away. For me, these traits were part of his character, and reminded me of our adventures together. Yet, to Ceri, he was an old wooden thing that made her laugh first, and now had turned her nervous.

The brief trip Erin and I had made to Lobster Lake years previous hadn’t given us time to explore, so I was not expecting a vista as we rounded the point. All at once, shorelines green on either side, our gaze shot toward the immense emerald block of Big Spencer Mountain rising neatly above a sandy spit that reached into the lake. Our paddle blades hung in the water.

“Paddle, please,” Ceri requested, clearly uncomfortable with our drifting arc. After we lingered some more, and the bow got a little closer to the shoreside brush, she hollered, “Paddle!” Okay. Okay, but I was just starting to relax.

We found the trailhead, but the sign there indicated a 2-mile trail, one-way. It was humid and sweltering. Sumner’s head bobbed in and out of sleep, and Ceri whined as the mosquitoes flushed from the woods and found us. No sooner had we dragged the boat to shore, than it had to go back into the water. We paddled frantically into the middle of the lake, swatting all the while. Erin had Sumner in the bow, and before long he was cradled in a bundle of PFD and beach towel, fast asleep. Ceri slumped atop a collapsible camp chair and followed suit. With Big Spencer glowing at our backs, Erin turned to me with the widest grin I’d seen in days. “Canoe drive?” she said. At home, we often resorted to taking a drive in the car to wrestle Sumner down. Without his nap, he turned into a punch-drunk bear cub. Even life with Ceri, who had long ago outgrown her interest in daytime sleep, was easier if she napped. We took a final look at the mountain before returning to our strokes and the rhythmic creaking of TINTIN’s joints.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenThe “canoe drive” really turned out to be a viable method to settle the kids. Jerry Stelmok, master wood-and-canvas builder, once said that he never tired of gazing at the interior of a nicely finished boat. It’s true, the swirl and warmth of varnished cedar can mesmerize, and occasionally inspire a welcome dozing.

We reached camp and Ceri stayed asleep even as Erin transferred her to the tent. Then mom crashed alongside daughter. Sum, however, had awoken and upon landing had picked up a stick and was thundering around honing his inner screech owl. I gazed at him befuddled. He needed a calming activity. It took me a while, oddly enough, to think up taking him on another paddle. I plopped him back in TINTIN and handed him an apple. He fell silent and noshed. I quickly forgot about his restless state and we just paddled, father and son; wood and canvas—little on board that wasn’t born of the earth.

His body swayed with each of my strokes as we crossed the cove. We paddled to another beach, but didn’t go ashore. We glided, surrounded by the forest’s soldiers of green and eroded Swiss-cheese-styled stone. I looked back at our camp hidden among the trees, above that perfect beach, and wondered if Ceri and Erin were up. As the boat drifted, Sum exclaimed.

“If we don’t paddle, wind take us where wind want to!”

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenThe camp kitchen is our central gathering area. I’ve always taken pride in keeping it neat and clean, but parenthood has required an adjustment from my persnickety past. I don’t often have the time for the perfect tarp setup or keeping the kitchen pack basket organized. Just getting the dishes done before the next meal is a success.

On Father’s Day morning, with just one eye open to the world, I watched Erin, clad in raingear, pick her way over our sleeping bags. Moist air and gray light filled the tent. It was far too early to be awake, yet I knew she was headed out to make a special breakfast for me. The night before I’d had a simple and silent wish to sleep in. The likelihood seemed so preposterous I had chuckled aloud. Yet, somehow, it was unfolding. Flocked by sleeping cherubs, I let my bones settle. Once more, I was lying dry while a rainy day let loose inches away. Too elated to fall back to sleep, I pondered my good fortune. Should I read? Take notes? Instead, I remained lost in thought. The kids awoke, snuggled in, and even agreed on what book to read.

Later, we hunkered down in our camp chairs, safe under the bug tarp. Our clothes were damp, particularly Erin’s. She had been cooking for over an hour beneath a not-quite-wide-enough kitchen tarp. Our hair was matted and we scratched bug bites, but we were together in a beautiful place, all smiles, about to share a breakfast of comfort food cooked over an open fire. Erin handed me a hot mug of coffee before sliding the lid from the Dutch oven. A puff of cinnamon-bun sweetness filled our meshed-in space. The kids wiggled in their chairs.

“I have a big mouth, so I have a big frosting,” Sumner declared.

“I need the largest one,” Ceri countered.

After minutes of eating in a silence broken only by wind in the branches and a spatter of wetness against the tarp, Ceri spoke up.

“I think every year for Father’s Day and Mother’s Day we should come here and eat these,” she announced. Then she added with a sticky grin, “I love this day!”

During a digestive lull, Ceri turned to me. “Do you want to go on a paddle with me? On the same route as Sumner.” My affirming reply was nearly a shout.

Donnie Mullen

Donnie MullenCeri started carrying around birch bark after I told her that the native peoples built canoes with it. I think she was plotting her own one-off. Birch bark also meant campfires and having “for real and true” (Ceri’s phrase) s’mores over the campfire. Weeks after the trip, when asked to describe the adventure, Ceri answered: “campfire…marshmallow…CHOCOLATE.”

Later that day, while we prepped dinner, Erin turned to me. I was still thinking about my paddle with Ceri and how she had leapt from TINTIN, cove after cove, eager to collect freshwater mussel shells. The rain was gone, though the sky was still overcast. “It’s a lovely lake…but the bugs,” Erin said. Her tired eyes lingered on mine.

I was tired too. Our sleep routine hadn’t improved as we had hoped it would. The previous night Sumner had been running around barefoot, hours after his normal bedtime, howling like a feral imp. Even still, I didn’t want to entertain leaving a night early.

“I’d kinda like to follow through with our plan.” I said, as a surge of guilt shot through me. It being Father’s Day, I knew my vote carried an unfair advantage.

“Okay,” she hesitated. “Let’s ask the kids.”

Ceri didn’t have to think about it: “I never get to play on the beach this much.”

Sumner nodded happily, then added: “Can…can I play my truck, possibly, again?”

Erin Mullen

Erin MullenI built TINTIN in 2000 to paddle the Northern Forest Canoe Trail and together, TINTIN and I made the first known complete passage of the 700-mile route. When I became a parent I left TINTIN behind for a while, but a mingling of my canoe and my children has begun. Aside from romantic notions about raising a new generation of wood-and-canvas aficionados, I hoped our canoe trip would make lasting memories and contribute to their balanced upbringing.

On our last evening, we all gathered in the sand as the heat of the day was finally lifting. The warmth of the sun after the recent inclement weather was a gift we all felt. Sum, caked in sand dust and flush from hard play, leaned against his mom. Peanut butter was smeared across both cheeks. He patted her on the thigh. Ceri, in her pajamas and slippers, fresh from beachcombing, touched down beside me for no more than a minute.

I noticed her looking at TINTIN, who was overturned nearby. The shellac on the two-tone hull was ablaze in the late-day sun.

“Dad,” she said. “You’re gonna have TINTIN a long time.”

I nodded.

“Like 20 years probably,” she added, confidently.

“For sure,” I agreed. “Someday, you’ll get him.”

Without responding, she dashed off to the water’s edge, and I tried not to tread too deep into my hope that one day she or her brother just might really want him.![]()

Donnie Mullen is a writer and photographer who lives in Camden, Maine, with his wife Erin and their two children. In the winter of 1999-2000, he built TINTIN and christened the canoe the following summer during his voyage along the 740-mile Northern Forest Canoe Trail, the first modern-day passage.

This article should be posted to someplace on the Internet where everyone in the world can see it. This is one of the most family oriented stories I have seen on a very long time. These children will ever revere and remember this special time spent with their family on this adventure. God bless these parents for making this adventure available to their children. May their tribe increase!

I agree with Casey. What a great article, Donnie! It brought back memories of camping with my family almost 55 years ago in the Ochoco National Forest in Eastern Oregon and with my own children in the San Juan Islands of Washington State. These kids will likely want to share similar adventures with their children. What a legacy.