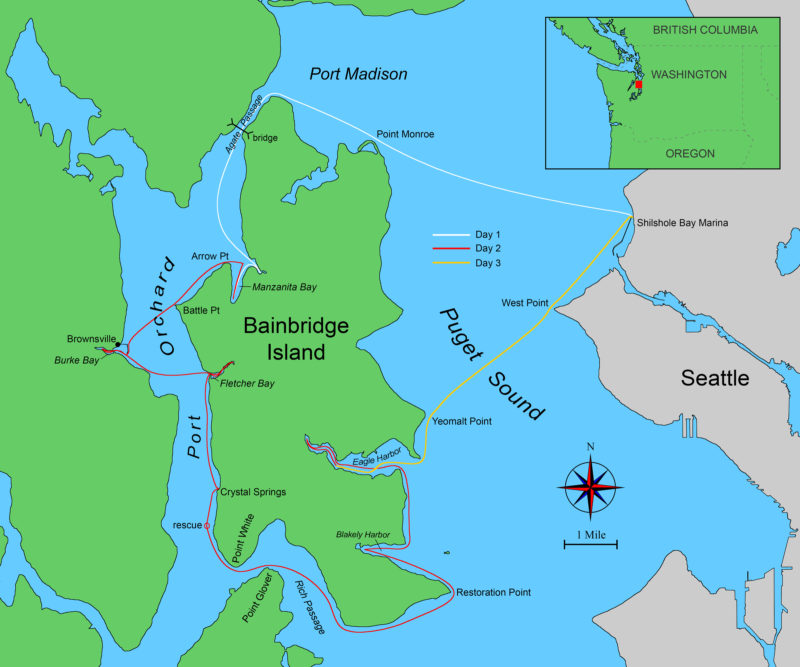

For the past three decades that I’ve sailed, rowed, and paddled Seattle’s Salish Sea, Bainbridge Island has always been the far shore, an inconspicuous streak drained of color by distance and an easily overlooked divider between the gunmetal-gray waters of Puget Sound and the serrated skyline of the Olympic Mountains. I’d made the 4-1/2-mile crossing to the island a half dozen times, always to the same cove on the northern end, and the only glimpses I’d ever had of its west side were from a highway bridge crossing from the mainland.

I’d lost most of the summer, first to the pandemic and then to the miasma of wildfire smoke that blanketed Seattle, and didn’t want to let August slip away without at least a short cruise. I launched ALISON, the Caledonia Yawl I built in 2005, from the ramp at Shilshole Bay Marina. The tide was out and if there was a breeze blowing, it wasn’t dipping down over the breakwater and seawall. The dock was so low that any wind there might have been was skipping past. I didn’t bother setting the masts, but lowered the outboard into its well, assuming I’d make the crossing to Bainbridge under power.

With the outboard at an idle, I steered around the tide-blackened boulders at the end of the breakwater, throttled up, and steered for Port Madison on the north end of the island, which was 5 miles distant and only barely distinct from the paler blue-green wooded mainland beyond it. As I brought the outboard up to 2/3 throttle, the rattling in ALISON’s hull smoothed. A few hundred yards out from the breakwater, the water was only rippled, without a discernible pattern, so I stopped the motor and coasted to a stop. The breeze I had felt on my face was only the air I was moving through. A few hundred yards farther into the Sound, the water was darker, and the apparent wind had shifted slightly to port. I stopped again and the breeze remained as ALISON slowed.

Roger Siebert

Roger Siebert.

I set the mizzen mast, with its sail wrapped around it, into its partner, and pushed the clew out with the sprit. Sheeted in tight, it pushed the stern away and brought the bow into the wind. I lifted the main mast, a solid 17′ stick of laminated spruce, until it stood like a caber in front of me, then lifted it over the foredeck and lowered it to its step. I unrolled the lugsail, tied the halyard to the yard and the downhaul to the boom, then hauled it up. Backwinded, the wall of white cloth pressed against my face. I cleated the halyard, snugged the downhaul and moved aft to push the boom out against the wind to force the bow over. ALISON surged forward. The outboard was still in the well, which was now noisy with sloshing water. The prop was still engaged and was being dragged through the water fast enough to crank the motor. I shifted to neutral and stopped the clicking coming from under the cowling. ALISON was sailing well with only an occasional touch on the tiller from me, so I lifted the outboard from its well. With that drag removed, I could feel the yawl accelerate and the water in the now empty well got noisier and spilled over the top and into the cockpit. I lowered the outboard into its chocks alongside the well. The plug for the well was close at hand under one of the removeable bench tops, and after I pressed it into position, ALISON stopped plowing up water.

Settled in at the helm, I was making good speed, 5.2 knots by the GPS. The shore I’d left was shrinking with distance, with the rows of white and pale gray masts behind the breakwater clustered together like the teeth of a comb. Seattle is a city of trees and hills, so on land I can never see very far into the distance. In the middle of the Sound, the land all around it bows low, and the sky fills the perimeter. People living in prairies might take seeing so much sky for granted. For me, being surrounded by a faraway horizon feels like being freed from a cage I didn’t know I was in.

The clouds overhead were all of a piece and lumpy like old cotton batting, with just a few bits of blue showing where it had been worn through. The daylight filtering through the clouds cast no shadows in the boat.

Photographs by the author

Photographs by the authorWith a southerly blowing straight up the Sound, I had a good reaching breeze and broke out the mizzen staysail for the crossing.

With the big balanced lugsail on the downwind side of the mast, it was taking its best shape and drawing well, even as the wind faded until the boat was barely heeling. I pulled the mizzen staysail out its bag, hoisted its peak on the mizzen’s unused halyard, and pulled the pennant on the clew tight around the jamb cleat on the front of the ’midship bench. Settled in with her full hamper, ALISON picked up to 4-1/2 knots.

The mizzen is rather finicky about the wind, and behaves itself only on a beam reach, so I steered a course that would bring me to Bainbridge Island well south of Port Madison. A single dolphin passed by me heading east, showing only the tight curve of its pale gray back just once, and didn’t surface again within sight. When I got within a mile of the island, I dropped the mizzen, spread the main out to starboard, and ran northward.

With the bow aimed right at Point Monroe, the crossing is almost over.

Point Monroe, the northeast cusp of Bainbridge, is a curved sandspit bearing beach houses, crowded nearly eave-to-eave. Rounding a few dozen yards from shore, I lost most of the wind and ALISON crept along toward the turn south around the next point, a half-mile away. The sunlight found a gap in the clouds and in the still air, its heat stung my bare arms. I pulled my red-and-white umbrella out of the bow and hid in its shade.

The turn coming up would head me south into Agate Passage, the mile-long, 300-yard-wide connection between Port Madison, a bay actually, and Port Orchard, a 150-mile-long inlet. I’d have the flood tide in my favor, but the wind would likely be on the nose. Rather than risk tacking in a strong current, I set the outboard back in its well, started it up and got moving, letting the sails luff.

I approached the bridge at Agate Passage under power with the current in my favor. I passed under the bridge just 15 minutes before the peak of the flood, which would hit 5.8 knots.

The wind in the passage was fluky and I ducked under the boom as it bounced from side to side. Motoring at less than half throttle, but with the flood pushing, I closed the distance to the bridge quickly. I steered for the east side of the channel and raced by the concrete pillar where the water was humped up on its upstream edge. I passed through, uneventfully, 25 minutes after the projected peak flow of 5.9 knots.

While the water under the bridge was whorled but without waves, the racing current plowing under a southerly with a good 4 miles of fetch kicked a short, steep chop that sounded like a river tumbling over a rocky bed. I steered west to the smoother water along the Bainbridge Island shore. The wind was good, worth a beat to windward, so I pulled the outboard and plugged the well. I made good speed, but then I noticed the island was slipping by in the wrong direction. I was in a back eddy and moving north. I came about and over the bow saw the ink-blue current sweeping by carrying a string of marker buoys south, speeding in the direction I wanted to go. I connected the dots of the dozen or more buoys to a 20′ motor vessel with a red hull—a research vessel—retrieving buoys upstream from me. When ALISON plowed into the chop, she slipped sideways as fast as she was sailing forward. About ¾ mile from the bridge, the pilings and nets of a fish pen seemed to be motoring northward. The current occupied only a narrow swath and as soon as I sailed out of it into smoother water, the remaining buoys, riding the current, passed by me; coming about and reentering the chop I could catch up.

The current carried me almost two miles from the bridge. With the wind steady at around 12 knots I kept tacking; ALISON heeled, burying the leeward sheer plank until the outwale was just clear of the water. My chart and sunglasses slipped across the bench and dropped into the footwell. The top third of the mainsail was quivering forcefully, making the hull vibrate beneath me. The centerboard began to hum. My grip on the mainsheet was weakening, in spite of its twofold purchase, so I wrapped a turn around a tholepin on the windward rail.

I held a starboard tack and headed for Manzanita Bay. The wind eased in the lee of Arrow Point and I coasted across the mouth of the bay and into a narrow branch on its east side. ALISON ghosted around the first bend and when she ran out of wind, I crawled to the bow and paddled, with my toes nearly touching the water. Cedar and madrone leaned out from the banks and the branches of a maple brushed against the peak of the mainsail, spilling some brown, autumn-curled leaves into the water. Some of them fell so lightly on the water that they didn’t break the surface tension; the water curled up around them as a pillow does around a sleeper’s head.

The little arm of Manzanita Bay meanders inland for about a half mile. A few dozen yards beyond this bend, I was turned back by shallow water.

I paddled around another U-turn bend and when the bottom showed itself just beneath the water’s surface I turned around. When there was enough depth, I placed the outboard in the well and motored out. Where this winding inlet joined Manzanita Bay proper, houses were perched on the banks above me. One had a wooden deck with a railing; one of the posts had a whirligig on it with four toy catboats chasing each other in circles in the breeze, perpetually running, reaching, luffing, tacking, reaching, running.

While there was a bit of a breeze blowing from the head of the bay, it was time to call it a day and drop the anchor. I motored south to the glassy-smooth water at the end of the ¾-mile-long bay. I killed the motor and left the helm to get ready to anchor. There was no sign of any wind on the water, but the tall mainsail was evidently catching a breeze higher up, enough to start ALISON sailing in circles, running, reaching, luffing, tacking, reaching, running. Each loop was a few yards downwind from the last one; I held the depth sounder over the side and when I had 20′ of water, I lowered the anchor.

Not long after I got the canopy set up over the main cockpit, it began to rain in earnest.

A moment later the water was speckled with drops of a light rain, so I quickly pulled the dodger up off the forward part of the cockpit and set the two PVC-pipe hoops and the canopy over the aft part. ALISON was buttoned up just before a heavy, soaking rain began pelting the covers.

Buttoned up against the rain, the cockpit is ready for kitchen duty.

The galley box I’d built for the boat was in a storage unit, so I made a new smaller one around a compact butane/propane stove.

I set the galley box, which had been upside down and serving as a thwart during the day, in the main cockpit, opened it up and got the stove set up. For dinner I sautéed wild-caught shrimp with sliced celery and fingerling potatoes.

The dodger forward covers the forward end of the cockpit, creating a protected, if snug, sleeping space, but I prefer spreading out in the main cockpit.

To convert the cockpit from kitchen to bedroom, I lifted the floorboards and set them on ledges, even with the benches. That gave me a sleeping platform almost as big as a queen-size bed, with plenty of room for a large, 4″-thick, self-inflating sleeping pad. With one unzipped rectangular sleeping bag as a bottom sheet, two more for covers, and my pillow from home, I’d be as comfortable as I’d be in my own bed.

It didn’t take long to fall asleep. The water was perfectly still, so the masts weren’t thumping in their partners and there wasn’t even any gurgling from the laps at the waterline. I woke once in the middle of the night and peeked out. ALISON hadn’t moved. The two sailboats anchored in the middle of the bay had their masthead lights on, each reflected as a single bright dot on the water. I wagged the rudder to check for luminescence in the water. Pale-blue sparkles swirled from the blade like sparks from a dying campfire stirred with a stick.

I motored to the mouth of Manzanita Bay with the covers still up. I took them down before heading out into Port Orchard.

I was up a little after 6 a.m., well rested. I retrieved the anchor and, with the canopy and dodger still up in case I wanted to have breakfast early, motored to the mouth of the bay. Conditions on Port Orchard looked fair, without too much wind, so I took the covers down, tidied up, and got underway.

I stayed close to shore along evergreen woods from Agate Point to the driftwood-strewn spit of Battle Point. To the southwest, 1-1/4 miles across Port Orchard, was the marina at Brownsville. The wind was blowing from the south at 10 knots, so the crossing was a bit bouncy, but the waves were not yet whitecapping.

The ebb was pulling Burke Bay down, but the current flowing under the bridge wasn’t running too fast to motor through.

I circled around to the back of the marina to a concrete bridge that carried a road over the 30′-wide inlet to Burke Bay, a backwater that I’d noticed on the chart. The bridge might have been high enough for the mizzen mast to clear it, but not the main. I lowered both into the cockpit.

The ebb approaching the middle of a 12′ drop and the strong current under the bridge was more than I wanted to row against, so I set the motor in the well and powered through. The flow created a tongue of smooth water creased along its edges by the ripples bent around barnacle-covered rocks. I looked over the side as I passed under the bridge and saw more rocks, which would make the passage even narrower. I wouldn’t have much time in the bay.

I was ashore here in Burke Bay only a few minutes, but I could see the water level dropping.

The chart showed Burke would dry with the tide and with a minus 0.9 low, the water would be gone well before low slack. I gauged the depth by the slope of the exposed muddy banks on either side. Just shy of ¼ mile in, the color of the water turned suddenly from dark green to a mottled brown. I’d run out of depth and killed the motor to save the prop from hitting the bottom. I scrambled to the bow with the paddle and turned the boat around. I stopped at a muddy outcropping covered with broken bricks and stepped off the bow. At the water’s edge there was a bone—half a rib, turned the color of turmeric—and the top of a brown glass bottle with PUREX molded on it.

I shoved off into deep water and motored back to the bridge. It was clear that the water had dropped in the short time since I’d first passed through. There would have been enough room to row through then, but not now. I lined up on the middle of the swift-flowing water, twisted the throttle for a burst of speed, then killed the engine to protect the prop. ALISON sped under the bridge, missed two barely submerged piling stumps, and came through without a bump.

The entrance to Fletcher Bay is narrow and the ebb created a strong current. I arrived at about 9:30, halfway through a falling tide that would make the gap impassable.

I hadn’t had breakfast yet and thought Fletcher Bay, on the Bainbridge side of Port Orchard, would offer a quiet spot. The mile-long crossing, out of the lee south of Brownsville, was in waves taken on the beam, making ALISON roll uncomfortably. The water was smoother in the crease in of Bainbridge’s shoreline that led to the opening to the bay. The mouth of the bay is nearly closed off by a gravel spit, with steep banks rising 10’ above the water. Inside the bay I kept running into shell-strewn shoals, turning the motor off, and paddling from the cockpit until I found the channel running along the inside edge of the spit. The narrow bay was straight enough to see its half-mile length from one end to the other.

The inner reaches of Fletcher Bay were woodsy and quiet, and would have made a good place to stop for breakfast, but all of this water would soon be gone.

At the east end, the houses were estates, really, with sprawling groomed lawns and gardens, and the deeper I motored in, the more modest the houses were and surrounded by tangled stands of second growth red cedar, with those closest to the water leaning on curved trunks out over the muddy intertidal slopes. At the head of the bay, a willow, bright green against the dark conifers, had its hanging branches shorn off straight at the high-tide line. I peeked in the motorwell and saw broken clam shells just inches below the propeller. If I stayed even for a quick breakfast, I’d get trapped.

Bucking a stiff headwind running the length of Port Orchard, I was glad not to be sailing, and to have chosen the Caledonia Yawl for this trip. Neither of my other cruising boats are as well suited to plowing into a chop.

I made my way back out to Port Orchard and worked south along the shore in waves that had grown enough in the past few hours to cause ALISON to pound into the troughs and send white spray flying to either side. In the distance, about 4 miles away where the inlet veers to the west, a gray scrim of rain and mist fell to the water, concealing the land. The clouds above me were soon doing the same and before my clothes could get damp, I put on my cagoule. Covered from head to ankle against wind and water, I immediately felt warmer.

I finally stopped in the lee of the point at Crystal Springs and cooked a late breakfast of scrambled eggs. When I made the new galley box I hadn’t realized it was too small for my plastic plates, so I had to cut one down to size. When the galley was packed up with its lid on, I’d flip it upside down and use it as my seat for motoring.

Two miles from Fletcher I stopped in the lee of a small point at Crystal Springs. There were a half-dozen mooring buoys there, all unoccupied, so I slipped the painter through the eye of one and led the end back to the boat so I could make a quick departure if someone decided to chase me away. The rain had stopped and I took advantage of the break in the weather to take my cagoule off and make my late breakfast: sautéed purple potato slices and scrambled eggs with toasted banana bread for dessert. While I was eating I spotted a yellow kayak fighting to windward a quarter mile or more from shore. That worried me so I took a look with my binoculars. It was a tandem sit-on-top kayak and both paddlers were wearing PFDs. If they were to capsize, they wouldn’t have as hard a time rescuing themselves as they would have with a sit-inside kayak. Well beyond the kayak I saw a single white sail, moving quite fast, and guessed it might be a high-performance sailer like a Laser.

As FREE SPIRIT towed the capsized daysailer toward shore, I followed, picking up gear that floated free.

When I finished breakfast, I filled the outboard’s integral tank and headed out. The wind had strengthened to about 20 knots and the waves were about 2′ high. The little 2-1/2-horse outboard was doing well and I kept the speed low just to ease the pounding. I scanned the water for the kayakers and didn’t see them, but I did see a large sloop a quarter mile offshore, without any sails up, going nowhere. As I got closer I could see it had an inflatable dinghy in tow and there was a small capsized boat nearby with its centerboard and rudder sticking straight up. I veered away from shore and pounded through the waves to help.

The canoe-stern sailboat was FREE SPIRT, skippered by a man with a full gray beard and wearing a black watch cap. A man of about 40 was in the dinghy and I figured out he was the sailor. The sailboat, BUNNY WHALER, was a 17′ Boston Whaler Harpoon, now in tow, still bottom side up. I asked the FREE SPIRIT skipper if I could help. He said he would go as close to shore as he could, and I might be needed to take over from there.

I trailed BUNNY WHALER. A sail bag popped up behind her so I came alongside it to bring it aboard. With water in all of the folds of what appeared to be a spinnaker, it was far too heavy to pull out of the water without pushing ALISON’s rail dangerously close to the water, especially while broadside to the waves. I kept a steady pull on the bag until enough water drained out to bring it aboard. I motored back toward BUNNY WHALER, and picked up a coil of orange braided line that had drifted free.

FREE SPIRIT turned into the wind about 100′ from shore and her skipper dropped the anchor. The Harpoon sailor pulled his boat close and crawled across its bottom to the centerboard. The boat didn’t budge. He tried several times to right her without success while drifting downwind. To keep ALISON from wallowing in the trough, I motored in slow circles, gunning the motor each time I had to turn her bow into the wind.

After FREE SPIRIT anchored in water deep enough to be safe, the sailor tried to right his boat, but it wouldn’t budge. One of his neighbors came out in a dinghy to lend a hand.

BUNNY WHALER drifted close enough for its skipper to swim the painter to it and tie her off. He swam to shore and I delivered the flotsam I’d collected to a man who had launched a dinghy from the beach to help. The capsized boat would wait for whatever resources she’d need to be righted.

I rounded Point White and entered the narrowest part of Rich Passage just as a ferry was charging through.

I continued on my way south toward Point White, and the rain started again. Just after I put my cagoule back on, it came hammering down, hitting so hard that more drops of salt water splashed up for every raindrop that fell, turning the surface a glittering bright silver. The wooded hillside on the far shore of Rich Passage became an indistinct gray shadow behind the scrim of falling rain. I rounded the point just as a ferry, the 360′ CHIMACUM, emerged from the murk, crowding the narrowest part of Rich Passage. I hugged the north shore until it passed, then steered out to take its wake on before it steepened in the shallows.

The cloudburst was short-lived, but it had poured enough rain into the cockpit to rise above the floorboards. I pumped it out as I headed east, angling across the pass to Point Glover. There the engine quit. I was close enough to the south shore that I didn’t have to row to get clear of the ferry route, so I let ALISON drift as I tried to get the motor started again. There was still gas in the tank, but I topped it off, and kept pulling the starter cord. In the 15 years that I’d had the outboard, it had only failed once, after ethanol-laced gas gummed up the carburetor. After cleaning it, I fed it on ethanol-free fuel. The motor had served reliably for so many years that I wasn’t angry at its failure, just saddened that I might have asked too much of it for too long. I let it rest for a few minutes, pulled the cord again, and it coughed to life.

As I made the turn around the south end of Bainbridge, there was much more room on Puget Sound to share with the ferries.

I crossed back to the Bainbridge Island side of Rich Passage and rounded the south end of the island. Houses crowded the shoreline, set between a 200′-high, evergreen-covered bluff and the tide-bared foreshore, carpeted with seaweed in dark shades of green and brown.

From the entrance to Blakely Harbor, I got a good view of Seattle’s Space Needle rising beyond Blakely Rock. The first time I saw the Space Needle, I was 9 and visiting the World’s Fair with my family in 1962.

As I worked my way along the broad, mile-long, arc of Bainbridge’s south shore, the crenellated silhouette of Seattle’s downtown skyline, 8 miles distant, slipped out from behind the island’s blunt slope of trees and houses. At Restoration Point, I turned westward into Blakely Harbor, a mile-long notch flanked with gentle slopes patched with sand and shingle. I nosed ALISON ashore next to an arched steel footbridge the spanned an opening in what looked like a breakwater of piled boulders.

The concrete building at the west end of the inlet once was the power plant for a lumber mill that operated here.

The gap was flanked by masonry walls of irregular rectangular stones, stained black with age. The tops of the walls were left jagged by missing stones, but at one time must have supported a different bridge. At the end of the 19th century, Port Blakely was a very busy place, with the Hall Brothers Shipyard on the north shore producing scores of sailing ships that carried cargo along the country’s West Coast, and here where I’d come ashore was the Port Blakely Mill Company’s lumber mill, in its day the largest in the world. At that time, the gap between the stone walls led to the pond that kept the logs that would be dragged into the sawmill.

The last part of Blakely Harbor to be filled by the flood tide is a pond that was once used by the lumber mill to hold logs. When I arrived, I could have steeped across it on the stones.

The pond, at least as it was when I arrived, was a muddy basin about 200 yards wide, dotted with green patches of seaweed and with the stumps of pilings that had rotted down to within inches of the mud. Just beyond the beach where I tethered ALISON was a concrete building splashed from top to bottom with overlapping layers of graffiti.

The interior of the building is entirely covered with spray-painted graffiti. The concrete walls have been painted so many times that they are smooth and glossy.

The blocky structure had been built in 1907 to generate power for the lumber mill. I crawled into the building through an opening below floor level and pulled myself up into the interior. The walls were covered with spray paint in so many layers that the concrete had lost its texture and was slick and shiny. The mix of different styles, from illegible tags to works of skilled artists, was oddly appealing.

By the time I was ready to leave, the gap feeding the pond was a deep, fast-flowing stream.

I’d poked a stick in the sand at the water’s edge when I’d landed; it was now nearly submerged by 1’ of water. And where there had been a trickle of water sifting through the rocks under the footbridge there was now a surging uninterrupted stream flooding into the pond. It was too early in the day to stop for the night so I motored out of Blakely and headed north 1-1/2 miles to a second inlet, Eagle Harbor.

The entrance to the harbor is protected by a peninsula surrounded by a corrugated wall of interlocking steel-sheet pilings that makes it look like a fortress. The land it surrounds was the site of the Pacific Creosoting Company, established there in 1905. It treated logs with the coal-tar based preservative until 1988, when the Environmental Protection Agency forced its closure and eventually designated it as a Superfund cleanup site. There was a well-protected sand beach at the base of the steel wall on the harbor side of the peninsula, but I opted to pass it by.

Eagle Harbor is home to the Washington State Ferry Maintenance Facility and a half-dozen ferries were parked there.

A half mile farther into the harbor, a half-dozen white and green Washington State ferries were clustered around the maintenance facility on the north shore, and beyond them, recreational boats filled a crowded marina and swung on paid buoys in mid-channel. The south shore bristled with private piers and docks. I was worried that I wouldn’t find a quiet place where it would be OK for me to anchor for the night.

I followed a bend to the northwest to a second bend, to the southwest, where a marker buoy in mid-channel had a sign wrapped around it reading “Aquatic Conservancy No Motoring.” I pulled the outboard from its well, tapped two sets of thole pins in their sockets, and snapped the halves of my sectional oars together. The shores of Eagle Harbor’s western extremity were lined with low-lying brush and grass, and the few houses there were set back from the water. It would have been the perfect place to anchor, but I didn’t want to impose upon the sanctuary, so after a half mile of rowing brought me to the end, I turned around and retreated.

I discovered at breakfast that a whole portobello mushroom was more than I could eat at a single sitting.

I found a gap between private piers on the south side, less than a half mile outside of the conservancy area. A single-masted trimaran was already anchored here, a liveaboard, judging by the tender trailing from the stern and the tarps over the cockpit and bags of gear on the foredeck. I dropped my anchor between the trimaran and shore. It was only about 5 p.m., but I was getting hungry and set up the galley before covering the cockpit for the night. The sun was still bright, but lowering itself above the treetops at the crest of the land, and casting beveled shadows of ALISON’s sheer across the cockpit. For dinner I sautéed cubed mahi-mahi fillets with diced onions and purple potato slices. I hadn’t had lunch after my late breakfast and the meal went down well, served hot in a bowl that I’d turned from a locust windfall.

With the dodger and canopy up, I turned in early. I woke once in the night. The boat was still and I heard only the distant croak of a heron and the whisper of a car driving by on a road hidden behind the trees. The sky was black and starless but the motorwell provided a window on constellations of blinking bioluminescence.

It began to rain at exactly 5:33 a.m., the moment I picked up my phone to check the time. It had been utterly quiet up to that moment and the rain didn’t sneak in with a few soft taps on the canopy, but spilled out of the sky all at once. I sat up in bed and looked out over the bow through the gap between the canopy and the dodger. There was only the hint of dawn and the landscape was drawn in shades of ash and soot. There were eight pinpoints of light above the water, five on shore and two on mastheads high over the water. The nearest treetops were intricate silhouettes while those a small fraction of a mile away were so indistinct that I mistook the ridge they were on for the edge of an advancing fog bank. I laid back down, pulled the still warm sleeping bags over me, and listened to the quiet plinking of rainwater dripping from the canopy into the cove. The wind picked up, rippling the water and the wavelets striking the boat’s laps made sounds like water gurgling out of an upended bottle.

Worried about making the crossing back to the Seattle side, I listened to the weather radio. Winds would be light from the north, building in the afternoon. I didn’t want to take a chance on a rough crossing, so I got dressed and started packing gear for the trip home. I had about an hour before sunrise, so I cooked a quick breakfast of scrambled eggs with chopped onion and the cap of a portobello mushroom. I just swished the dishes in the motorwell before packing the galley box and flipping it over to rest between the benches.

After spending a quiet night anchored between the trimaran and the shoreside house, I headed for home.

The rain had stopped by the time I was ready to get underway, and I could take the covers down, retrieve the anchor, and get the motor warmed up. I took it slow past the marina in case anyone was sleeping aboard one of the anchored boats, and sped up when I reached the harbor mouth. A ferry from Seattle was arriving, following the channel from the south, so I veered from my westerly course to let it pass.

The rays of the morning sun framed the Seattle skyline as I motored out of Eagle Harbor.

There was no wind ruffling Puget Sound and the water was bright and alive with syrupy smooth ripples. The morning sun had risen over downtown Seattle, its position behind the clouds made evident by the shafts of light radiating from clearings over the city. The water to ALISON’s port side was silver with the reflections of the overcast sky and streaked with indigo where the backs of the waves were just steep enough to peer into the depths of the Sound. On the starboard side the water painted the sky’s broad palette of grays in crisp-edged concentric ovals that winked open and closed.

The morning calm provided the best opportunity to make the crossing back to the Seattle side, leaving Bainbridge Island astern.

The outboard purred smoothly, pushing ALISON north at over 5 knots along Bainbridge Island’s west coast. When I reached Yeomalt Point, I veered to the northeast and set the bow on West Point. Halfway into the 3 ¼-mile crossing I passed through an eddyline littered with driftwood and seaweed picked up off the beaches by the week’s exceptionally high spring tides. I felt the hull shake and the engine suddenly labored, dropping the pitch of its purring. I hit the kill switch and looked down into the motorwell. The motor shaft had T-boned a wrist-thick piece of driftwood dead center and had held it there. I pushed it away and it floated up on ALISON’s port side.

While I had been underway, I had been focused on getting back home and, if not for the driftwood, I would have missed taking in the view from the middle of the Sound. Before I got underway again, I stood up and looked at its thin perimeter of land, pressed flat against the horizon by its own weight. Standing in my boat, hovering between the buoyant water and the weightless sky, I felt so much lighter than I had all year.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Magazine. He has been building and cruising in small boats since 1978.

If you have an interesting story to tell about your adventures with a small boat, please email us a brief outline and a few photos.

What a pleasant way to start the day, reading about a circumnavigation of “my” island! Agate Pass can be brutal; Rich Passage is usually better protected from the wind so there is less chop but the current runs fast, I’ve spent a lot of time with a lovely wake spinning out from under the hull with the shoreline staying firmly in place. There is a small watercraft campsite in Fort Ward, mostly used by paddlers; it is a bit exposed for anchoring out.

I keep my Oughtred-designed Eun Mara in Eagle Harbor. That trimaran has been there for years. You did well to not anchor in the preserve, the waterfront folks are quite “protective” of it.

Thank you for the tour, I’ve thought about sailing around the island but it is too easy to put off an adventure when it is in your own backyard. Next summer…

Great adventure. I live on Eagle Harbor. Before retirement I was always trying to con guys at work into my misadventures. One victim joined me in a one-day sail around Bainbridge in my old cold-molded International 14. Hit by all kinds of weather that day. Finally becalmed in the fast current & ferries of Rich Passage. Had one paddle between us & made it to shore. Then things went wild with the winds. We took off like we were on water skis. Big air the rest of the trip. Very fun… for me at least. BUNNY WHALER, an early ’80s Boston Whaler ‘Harpoon,’ has been in the R2AK (700 mile race to Alaska) twice! Great Island family.

Christopher,

I really enjoyed reading your circumnavigation account. It was very well written.

I too have a Caledonia Yawl. You made some very interesting enhancements, like the Mizzen staysail that I would like to know more about. Do you have a way to adjust this sail once it is raised?

Your bed looks much more comfortable than my current arrangement. Did you also modify the centerboard layout?

Thanks for the comment, Ricky.

The mizzen staysail just needs the sheet adjusted. There are two sheets, each with a jam cleat on the mizzen partner. Coming about require dropping the staysail to let the main swing across, either lowering the staysail’s peak or releasing its tack. There is a bit more information in “Mizzen Staysails Add Power,” in the August 2017 issue.

I built my Caledonia yawl with side benches that had ledges that would support the floorboards to make a broad sleeping platform. The centerboard trunk is offset to starboard and built into the bench system. In the lower left corner of each photo, you can see the red cord that pulls the board down and up. The trunk is the white panel beneath the bench in that corner.

Very fun read. Thank you. Had I known you were traveling by, I’d have hollered hello from Point White Dock that’s practically right in my front yard. Hmmmm…. or maybe not. The rain was pretty serious about then.

You hit all of my favorite places around Bainbridge Island. Manzanita Bay can be noisy in the summer months since it’s frequented by water skiers. Did you use your cagoule?

I did indeed use my cagoule. It’s now part of my regular boating kit. The wind and rain picked on as I made my way south along Port Orchard and I put my cagoule on to stay warm and dry. During the downpour, it provided me with head-to-toe protection and comfort. Before the cruise, I had made a PVC version of a kind of visor used by Aleut kayak hunters and I wore that under the cagoule hood to keep the rain off my face and out of my eyes. It was a great combination.

This was an excellent article. For 30 years, my wife and I did week-long canoe trips that often sounded like the weather in this piece. We have moved up to a 30′ trawler, but I’m building a Dave Gentry Whitehall to feed the small-boat addiction.

Wow, beautifully written. I confess to jumping in without reading the author’s name. Once I finished this little holiday of a read I scrolled back to the top and saw Christopher Cunningham. No wonder, I smiled.

Thank you

Intrigued by offset centerboard trunk you installed in the Caledonia. How did you modify the hull to do that? Thanks in advance.

I didn’t have to make any modifications to the hull. For the trunk to be flush with the benches, the board had to be a bit narrower, so made it a bit longer to keep about the same area. My Caledonia is the original 4-strake version, so I could move the trunk about 12” to starboard and still have it within the bounds of the very wide garboard. I didn’t need to fuss with fitting it over a planking lap and I just scribed the bottom of the assembled trunk to fit the curve of the garboard. Then I trimmed the trunk’s top level with the bench supports.

A delightful read! Fun seeing Bainbridge from the water, and it brought back so many memories of sailing and water. And such a clever boat. Thanks.

This is way late (but hey, you just posted this article again) — is your dodger construction documented anywhere? Or could it be? Seems very convenient for small open boats like this!

I made that long before Small Boats started and I didn’t think to document it for an article. I used a few books on boat canvas work as guides.I don’t now recall which books they were.