Paul Gartside, designer of the 10′ sailing pram Spitfire, says that he drew it with “youngsters in mind.” He describes it as a “neat little boat to learn to sail in and hopefully one that might instill the magic of a real wooden boat at an impressionable age. From the builder’s perspective [it’s] a great place to hone traditional skills.” A small transom-bowed lapstrake dinghy, Spitfire is a fun sail-and-oar boat for two people—adults as well as “youngsters.”

Before building the Spitfire, we had tackled a few other builds and were glad to have the experience—construction of this small boat is sufficiently complex that it would tax a beginner. Indeed, Gartside says of the design, “this [is] real boatbuilding. It doesn’t get much more challenging, regardless of size.”

Fani Skoulikidi

Fani SkoulikidiThanks to the warm dry weather on Syros, we were able to build the boat outside beneath a simple shade awning. We built the Spitfire upside down on a strongback, planking it in spruce because cedar is hard to come by in Greece. Once the hull was fully planked, we turned it upright for fitting out and decking, first painting the interior—the ends would never again be so easily accessed.

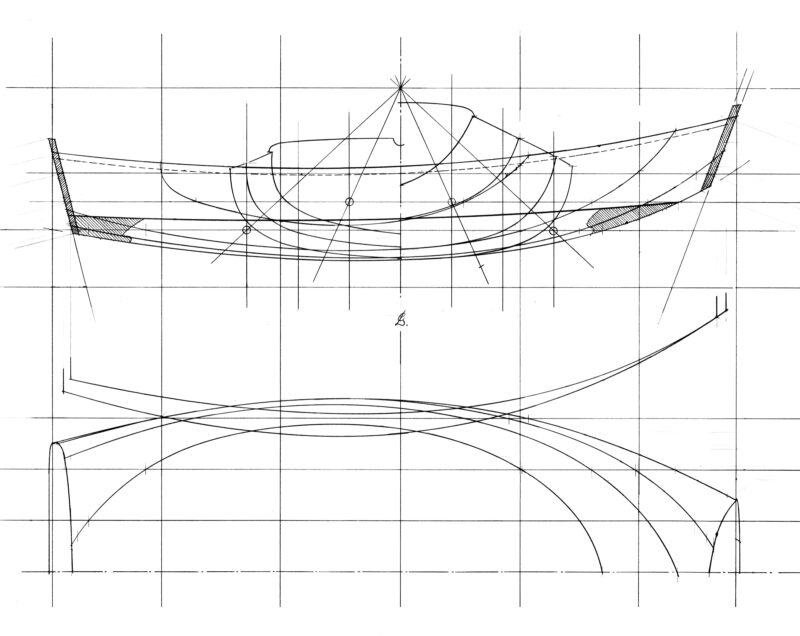

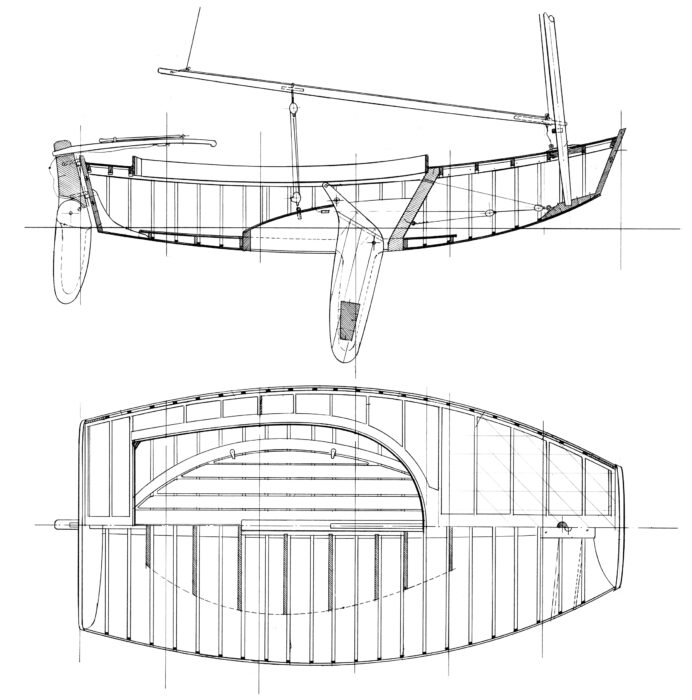

The hull, which requires lofting, is of traditional lapstrake construction with 10 planks per side on steam-bent frames. The four sheets of plans are detailed and provide the necessary information for an experienced builder, but there are no step-by-step instructions. The first sheet includes the lines and a table of offsets from which to loft the boat full size. The second provides details of the construction including the recommended types of wood, the thicknesses, the number and type of fastenings, the 10 lbs of lead to weight the centerboard, and other small details. The third sheet describes the setup of the strongback, and the fourth is the sail plan.

The Spitfire is built upside down on a strongback. We used pine for the centerboard, centerboard trunk, gunwales, carlin, floor timbers, deckbeams, deck, and rudder (which we built with a fixed blade, as we typically sail in deeper waters; Gartside’s plans detail a rudder with a kick-up blade). We used spruce for the planking and floorboards and also for the spars and oars. Gartside suggests Atlantic white cedar, 5⁄16″ for the planking and 3⁄8″ floorboards, but in Greece, where we live and built the boat, cedar is hard to come by. We used oak, as specified, for the keel plank, frames, transoms, rubbing strakes, coaming, tiller, and cleats. The plans note the hanging knees as being laminated, but do not specify the wood type; we made ours of solid oak. We also made our own blocks out of elm. For fastenings, we used copper nails and roves, and used silicon-bronze screws and bolts where needed. The deck is two layers of 5⁄16″ pine covered with 4-oz fiberglass cloth and epoxy.

To achieve the necessary curves, we steamed all the frames and the coaming. In the bow we wrapped some of the plank ends and applied boiling water to help bend them into the transom. As they cooled, we clamped them between curved blocks to help maintain their shape. We planed the ends of the planks to a feathered edge to bring them flush to the transoms.

Fani Skoulikidi

Fani SkoulikidiThe ends of the planks are planed to a feather edge to bring them flush into the transoms. From this angle, the Spitfire’s jaunty sheer is apparent; in a chop that high bow helps keep the boat and crew dry.

The designer estimates the build time of the Spitfire to be about 300 hours. For us, the project was slowed because we were not working on it full-time, and we were often forced to wait for weeks for materials to arrive from abroad. From beginning to end it took us roughly four months.

For its size, the dinghy is remarkably spacious. There is room for two adults and their gear. The plans indicate the placement for oarlocks but do not include seats, so a rower must sit on the centerboard trunk, which is a good position for the oarlocks but not the most comfortable; or, if the mast is not stepped, on the foredeck, which is more comfortable but something of a stretch. In either position there is still room for a second person to sit in the stern and steer.

Working from the plans we built 7′ 9″ straight-bladed oars with sewn leathers, and while these can be stowed in the boat mostly under the deck, occupying very little cockpit space, we find that when sailing with two people on board it’s better to leave them in the oarlocks lying on the sidedeck, where they are in easy reach should we need them.

Fani Skoulikidi

Fani SkoulikidiPaul Gartside’s plans call for a kick-up rudder but as we typically don’t sail in shoal waters and rarely require the rudder to lift, we went with a fixed blade. Both transoms rise above deck level. In the stern it allows for a sculling notch (partially hidden here by the rudder). The oars can be stowed in the boat, but we like to keep them in the oarlocks so they are out of the way but readily to hand when needed.

The finished boat weighs around 200 lbs, so a small trailer is best for easy transportation, and while it can be dragged down a sand beach—the keelband and half-rounds fitted along the first four plank lands protect the wood from damage—to carry it does require two or three people. It is far easier to find a launching ramp and launch straight from the trailer; the boat slides off and on the trailer with ease.

We live on Syros, a Greek island in the Aegean Sea. There are many deepwater gulfs and bays within easy access, and we have been happy with the boat’s performance. It is stable and feels safe when climbing aboard and moving around, even with two of us on board. When we are together, one of us sits forward and manages the sail (or rows) while the other sits aft, leaning forward to avoid the arc of the tiller when tacking or jibing.

Under oars, the boat tracks well, even when rowing into a choppy sea and light to moderate headwind. We have even rowed in a wind gusting 20 knots and the boat performed well, unhampered by weathercocking. In all conditions it is responsive to the helm or to a change in pressure to an oar, and rowing is a pleasure—although if you wanted to row for any distance, you would want to build a wider seat.

Clement Kalliambetsos

Clement KalliambetsosOn launching day, we rigged the boat on the beach and blessed it with a splash of local wine. The sailplan shows the sail loose-footed, but we added lacing. The single deep reef means this small boat can be sailed in stronger winds, although we would recommend a top wind strength of around 16 knots.

The boat’s rig is an unstayed mast with a 45-sq-ft spritsail. We have the sail permanently laced to the mast and boom, and we can be off the trailer and sailing in about 10 minutes. When sailing singlehanded, the helmsperson can sit on the floorboards or, if preferred, the aft deck (although here your body does impede the swing of the tiller, and you must duck down into the cockpit to avoid the boom when tacking or jibing). Sitting on the floorboards, it is comfortable to lean against the cockpit coaming, and there is plenty of room to get forward of the tiller and to change sides with ease. Thus seated, there is good visibility in all directions, and the mainsheet, run through a double block secured to a simple pad-eye mounted on the after end of the centerboard trunk, is within easy reach.

Sailing with two people is a little more cramped, and with the forward crewmember seated alongside the centerboard trunk, it is often easiest not to change sides when tacking or jibing.

The Spitfire is responsive to the helm, and we have found that trimming the pivoting centerboard helps to improve performance on all points of sail except closehauled when we keep it all the way down. The boat does well through jibes and tacks, finding its new course and picking up speed quickly, but on the rare occasion when we have been caught in irons, we’ve been able to quickly restore control with a couple of strokes of an oar. We haven’t measured our speed under sail, but being close to the water it feels fast.

Clement Kalliambetsos

Clement KalliambetsosFor a 10′ dinghy the Spitfire is surprisingly roomy. When the rig is up, the rower can sit atop the centerboard trunk but if the rig is down, they can sit on the foredeck, which is more of a stretch to the oars, but also more comfortable as a seat. In either circumstance there is plenty of room for two adults.

Like any small boat, the Spitfire has its limitations. We would recommend sailing it in protected waters and winds up to about 16 knots. Our local sailmaker followed the designer’s recommendation of a single line of reefpoints in the sail, and it is certainly comforting to have that one reef if the wind picks up suddenly. Fully rigged and with two people on board, seated low on the floorboards, the stability is good. The marked rise in the sheer forward, coupled with the raked transom bow, helps to keep the boat dry even in a stiff breeze and steep waves.

From building to sailing to rowing, we have been very happy with the boat, which we have named Φαφαφηνα (FAFAFINA). Not only does the design live up to Paul Gartside’s promise of being suitable for younger sailors, but also it has proved enjoyable for all ages whether sailing alone or with company.![]()

Ioanna Moutousidi and Giannis Bormpantonakis are boatbuilders from Greece. They studied traditional wooden boat building at Aprendiztegi (the Lance Lee International Boatbuilding School) in Basque Country. After completing their three-year apprenticeship, they returned to Greece where they run a workshop for building small boats and work in shipyards around the Greek islands.

Spitfire, Design #177, Particulars

Length: 10′

Beam: 5′ 1″

Depth of hull amidships: 1′ 5″

Draft centerboard down: 2′ 6″

Weight: 180 lbs

Sail area: 45 sq ft

Plans for the Spitfire, Design #177, are available from Paul Gartside Boatbuilder and Designer. Digital study plans are $20; printed study plans are $40 including shipping. A full set of digital plans is $150. The Spitfire is described by the designer in his book Plans & Dreams, Volume 1.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats readers would enjoy? Please email us your suggestions.

I love the deck! Gartside has a wonderful eye for line. His takes on a type regularly surpass all others in my opinion, even besting the fabled Herreshoffs. He mates practicality and tradition with yacht-level grace and balance of line. I’m yearning for his 7ft #80 as a tender for, later, something bigger, but there are two to complete in the progression between now and then and I’m less and less confident in my ability to complete beyond what I’m on.

A very attractive boat, and you did a beautiful job. It is very similar to a Howard Chapelle dinghy found in his book, “Boatbuilding.” His is 9 feet long, and about 3’10” in beam. He says the boat can be built strip planked, cold-molded, or lapstrake. When I made a model of it, I used lapstrake. The Chapelle pram is not decked and has a daggerboard rather than centerboard. I put a centerboard in my model, and a T-shaped seat/rowing bench to allow more than one rowing position. He shows a mast, but only gives mast and boom lengths, so I think you can play with your own rig details.

I note the lack of a skeg in this design. I see some prams have a sort of bow skeg in addition, which may be to help in tracking