I grew up with a peapod. It was 6″ long and my father had whittled it, probably before I was born. It was one of the many models he had made that taught me to appreciate the beauty of the forms of boats. I was especially fond of this delicate double-ender, but despite having built real boats for decades now, I never built a peapod. I very much liked the type, but I was unwilling to tackle the challenge of carvel planking. So, when I saw the John Harris–designed Lighthouse Tender Peapod from Chesapeake Light Craft (CLC), I was eager to row and sail this adaptation of the classic type, updated to easy-to-build plywood construction.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe plywood adaptation of the peapod has a combination of lapped planks on the upper strakes the edge-joined planks on the lower strakes. The smoother bottom is easier to cover with fiberglass and less vulnerable to abrasion.

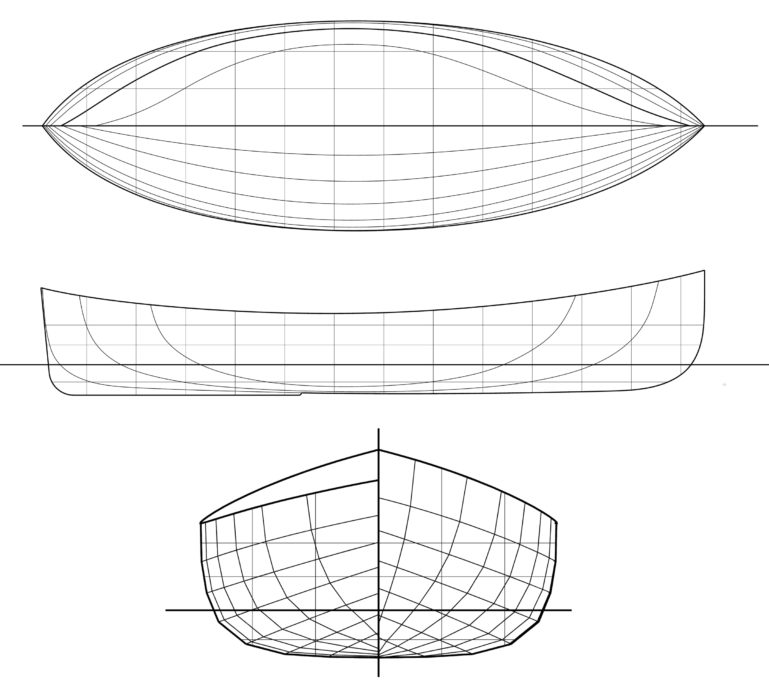

John had taken his inspiration from a working peapod built in around 1886 in Washington County, Maine. It was the same peapod I had been drawn to in American Small Sailing Craft. Author Howard Chapelle notes that particular peapod was, when the lines were taken off in 1937, the last of its kind ever built Its type was used for lobstering near Jonesport up to about 1938. John’s Lighthouse Tender Peapod has a shape very similar to the original working boat; the chief differences in the new boat are a sternpost that is nearly vertical rather than raked, and the absence of a keel, which allows his boat to sit upright on the beach.

The boat, built from a kit, is 13′ 5″ long with a beam of 52″, and is a combination of CLC’s LapStitch construction and standard stitch-and-glue. The three upper strakes are LapStitch, with overlapping edges, which cast shadows that highlight the curves of the hull. The lower three strakes are edge-joined, making it easier to apply fiberglass to the bottom and avoid the vulnerability of proud plank laps. The combination of different seam types isn’t as visually jarring as it might sound. I didn’t notice it until I crawled under the boat while it was resting in slings.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe thwarts are joined by plywood side pieces that aren’t intended as benches, but rather as part of a system that stiffens the hull for sailing. A block of flotation foam, painted black, hides in the shadow under the bow seat.

The seating arrangement includes stern sheets, a center thwart, and a seat forward that incorporates a mast partner at both its aft and forward edges. The three seats are made contiguous by narrow extensions that are somewhere between side benches and lodging knees. The combined structure, bolted together, gives the hull the stiffness to resist the torsion created by sailing forces. The plywood pieces are not glued to the hull, so they can all be removed for refinishing when the time comes.

Fixed underneath the seats are blocks of foam for flotation. The foam is painted with a flexible coating that resists chipping and wear. The coating is black and surprisingly inconspicuous in the shadows cast by the seats. The floorboards are fastened to the frames with stainless-steel screws and finishing washers so they too can be removed for maintenance. Aft of the centerboard trunk is an opening in the floorboards for a bilge pump.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe lever that operates the centerboard has loops of bungees to hold it in position. Note the black flotation blocks under the thwart.

The centerboard is braced by the center thwart and extends forward from it with an open slot for the lever that raises and lowers the board. Bungee loops slip over the lever to hold the board in position with some give if it strikes an obstruction while the boat is under sail. The rudder has a kick-up blade with a bolt and a star knob that adjusts the friction that holds the blade down or up. The skeg extends about 6″ abaft of the after stem before it curves upward. It allows the gudgeons to line up vertically, so the rudder is easy to attach while the boat is afloat and is more effective for steering than a rudder that pivots on an angled axis. The rudderstock has a fixed arm extending to starboard for a Norwegian tiller that reaches around the mizzenmast. I’d prefer a removable arm to make the rudder more compact when stowed, though that arrangement is more complex to build and would have to be much heavier. A cord connects the tiller and the arm, providing a very simple, flexible joint, which is kept from getting sloppy by tensioning the cord in a clam cleat at the forward end of the tiller.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe rudder stock has a fixed arm for the attachment of a Norwegian tiller, which works around the mizzen.

The spars are all rectangular in section with rounded corners. They’re tapered to minimize weight and achieve a pleasing appearance. The mainmast is laminated with three pieces of fir, and the mizzen is a single piece of spruce. In the kit they arrive with precut scarfs ready to be glued together. The main is a balance lug sail, loose-footed, and has an area of 73 sq ft. The mizzen is also a balance lugsail with its foot laced to the boom and has an area of 22 sq ft. The Peapod has an optional rig, a cat-rigged balance lug with an area of 79 sq ft.

Christopher Cunningham

Christopher CunninghamThe Peapod is a nimble boat under oar power and a pleasure to take out for a quick, uncomplicated outing.

When I stepped aboard the Peapod while it was afloat just off a cobble beach, its stability was readily apparent. I could lunge over the side and move about with ease. Sitting on the end of the center thwart, I rested my shoulders on the gunwale to look over the rail and still had plenty of support and freeboard. It was easy to imagine pulling a crab trap up over the side. My first task to get ready for sail was to lower the rudder blade. Leaning over stern, wrapped around the mizzen to reach the blade, was a further test of the double-ender’s stability. In a boat with a transom there would be some beam at the stern to support my weight off center, so I was surprised the Peapod didn’t mind having its tail end twisted.

Chesapeake Light Craft

Chesapeake Light CraftFor rowing through the lulls, the sails are easily dropped out of the way and the rudder blade retracted to clear the water.

With a fluky wind blowing at 12 knots and gusting to 15, I set out with the full main and mizzen set, just right for the conditions. For stiffer breezes, the first reef is to remove the mizzen and move the main from its forward position aft about 15″to its other step. The second reef is made by pulling the main about 24″ down to the boom in a traditional slab reef, which is made easy by the reefing lines on the luff and leech and three reefpoints. On a reach, the Peapod made 4 3/4 knots in 1-1/2′ wind-driven waves and rolling freighter wakes. The Peapod was quite lively and bobbed like a cork. The bow rose quickly and I never saw any spray, let alone have any come aboard. And I didn’t see any water sloshing up out of the open top of the centerboard trunk.

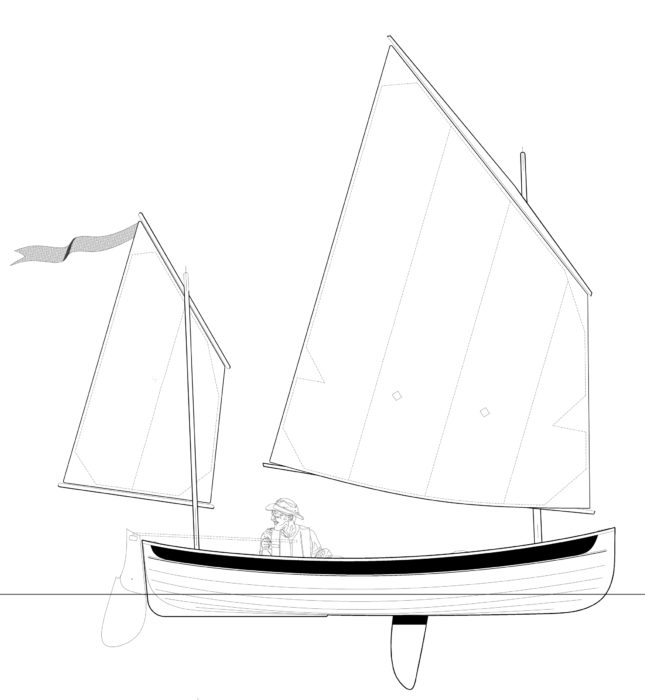

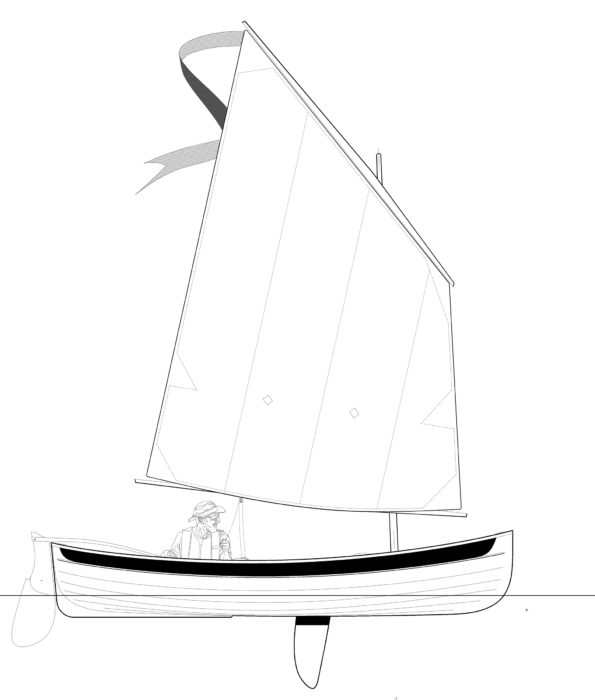

Chesapeake Light Craft

Chesapeake Light CraftThe yawl sail plan offers a total sail area of 95 sq ft.

The bow rounded up smartly with the helm a-lee for tacking, and then slowly crept across the eye of the wind; it didn’t get caught in irons, but I took to backing the main to snap it across. The Peapod did well to windward and in gusts resisted heeling quickly, giving me plenty of time to react by easing the sheet or rounding up.

I only sailed the Peapod solo, and for the gusty conditions I was most comfortable kneeling in the bottom rather than sliding across the center thwart. There was plenty of room for two more people. The full ends would give the additional crew room to move athwartships and shift weight to windward.

Chesapeake Light Craft

Chesapeake Light CraftThere is an optional sail plan for a lone 79 sq ft mainsail. With no mizzen in the way, a common tiller can be used.

For rowing, with both sails and spars resting in the hull and the rudder blade cocked up, the Peapod performed well. The retracted rudder barely touched the water so it didn’t drag or interfere with tracking or turning. The skeg gave the boat good directional stability without hindering maneuvering. The boat scooted along at 3 knots with a lazy effort, held 4 knots at an aerobic exercise pace, and did 4-1/2 knots in a short sprint. The Peapod has two rowing stations, one for rowing solo or with two passengers, and the other, about 32″ farther forward, for rowing with a single passenger in the stern. With three men aboard, the hull still shows two-and-a-half strakes above the water. There is plenty of freeboard. Chesapeake light Craft set the capacity at 650 lbs.

Chesapeake Light Craft

Chesapeake Light CraftWith three men aboard, the Peapod sits nicely on its lines and has plenty of freeboard.

With the Lighthouse Tender Peapod, Chesapeake Light Craft has brought a modern construction that is easy, inexpensive, and light to a traditional form that isn’t within reach of a beginning boatbuilder or well suited for recreational pursuits. It has the pleasing shape of its predecessor and the simplicity and ease provided by modern construction.![]()

Christopher Cunningham is the editor of Small Boats Magazine.

Lighthouse Tender Peapod Particulars

[table]

Length/13′ 5″

Beam/52″

Hull weight/160 lbs

Draft, rowing/6″

Draft, sailing/30″

Sail area/95 sq ft

Maximum payload/650 lbs

[/table]

Kits for the Lighthouse Tender Peapod will be available from Chesapeake Light Craft sometime in February, 2020.

Is there a boat you’d like to know more about? Have you built one that you think other Small Boats Magazine readers would enjoy? Please email us!

Working double-enders ran 14′ to 15′, usually 15′. Once summer people came to Maine, the size was shrunk to 13′ for recreation. Pleased to hear that the boat is as stable as it is. The working pods were rolled down weighting the bilge, the trap line taken up, and then rolled up right using the boat as a lever arm for a soaked wooden trap.

On this one, if it was up to me, I’d have section of the floorboards readily removable for bailing. Pretty much impossible to get the boat dry with just the pump. I’d also have a screw-in drain hole. And I’d figure out how to put in a stretcher. I’d also put in some kind of tube or box to guide that forward mast into the step so the mast can come down and up in a chop.

I am just finishing one of the CLC peapods. The original customer decided that he would rather have Doug Hylan 15’ design so I told John Harris to ship the parts even though the kit wasn’t a finished kit. So far things are going well and we hope to launch in the spring. I am looking forward to boat for boat comparison with the Hylan design. Will write up our notes.

Cheers,

Damian

Hi Damian,

Just wondering if you have any thoughts about comparisons between these two peapods.

Thanks

Michael

Neat little boat. Well done.

A very neat little boat. It is the time when less is more, a simple boat. We need to enjoy her for what she is and not complicate her and the rewards on water will abound.

Can I get plans only as I’m living in NZ?

This is the plan I want to build. Can a first time builder handle a kit by themselves?